'I Curse Your Preoccupation with Your Record Collection': the Fall on Vinyl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stop Smiling Magazine :: Interviews and Reviews: Film + Music

Stop Smiling Magazine :: Interviews and Reviews: Film + Music + Books ... http://www.stopsmilingonline.com/story_print.php?id=1097 Downtown Dedication: The Return of Polvo (Touch and Go) Monday, June 23, 2008 By Dan Pearson We could have flown out of Newark, landed in Charlotte, and just hit a barbecue spot in Reidsville, but this was after all the Polvo reunion and it deserved more. We needed to feel as if we were making the descent, notice the disparity in New England and Southern spring, endure interminable DC traffic and feel that we had earned our ribs and slaw. So, I packed the Malibu with I-Roy and U-Roy, stomached $4 gas and my friend Bose and I left from Connecticut in a rainstorm, both of us in fleece. Night one we spent at a Ramada in Fredericksburg, never made it to the battlefield or historic downtown, but instead drove down the divided highway to Allman’s BBQ. I’m wary of food blogs, but the culinary scribes were dead-on: best ribs I have ever had outside Texas, enviable pulled pork and slaw, notable sauce in the squirt bottle — all in an old corner diner with spinning stools. What a foundation, not only for the evening, which consisted of ice cold tap Yuengling and inebriated dancing to Def Leppard in the Ramada lounge, but for the show to come. Just a stateline south, yes, Polvo, the seminal math rock quartet, reunited at their Ground Zero, the Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro. In the morning, it was only better, the slow slalom down Route 40 country roads leaving trails of red clay and another barbecue platter at Short Sugar’s in Danville, Virginia. -

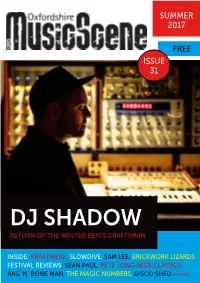

Dj Shadow Return of the Master Beats Craftsman

SUMMER 2017 FREE ISSUE 31 DJ SHADOW RETURN OF THE MASTER BEATS CRAFTSMAN INSIDE: KRAFTWERK, SLOWDIVE, SAM LEE, BRICKWORK LIZARDS FESTIVAL REVIEWS: SEAN PAUL, PETE TONG IBIZA CLASSICS, RAG ‘N’ BONE MAN, THE MAGIC NUMBERS, DISCO SHED & MORE OMS31 MUSIC NEWS There’s a history of multi – venue metro festivals in Cowley Road with Truck’s OX4 and then Gathering setting the pace. Well now Future Perfect have taken up the baton with Ritual Union on Saturday October 21. Venues are the O2 Academy 1 and 2, The Library, The Bullingdon and Truck Store. The first stage of acts announced includes Peace, Toy, Pinkshinyultrablast, Flamingods, Low Island, Dead Reborn local heroes Ride are sounding in fine stage Pretties, Her’s, August List and Candy Says with DJ fettle judging by their appearance at the 6 Music sets from the Drowned in Sound team. Tickets are Festival in Glasgow. The former Creation shoegaze £25 in advance. trailblazers play the New Theatre, Oxford on July 10, having already appeared at Glastonbury, their The Jericho Tavern in Walton Street have a new first local show in many years. They have also promoter to run their upstairs gigs. Heavy Pop announced a major UK tour. The eagerly awaited are well – known in Reading having run the Are new album, the Erol Alkan produced Weather Diaries You Listening? festival there for 5 years. Already is just released. (See our album review in the Local confirmed are an appearance from Tom Williams Releases section). Tickets for New Theatre gig with (formerly of The Boat) on September 16 and Original Spectres supporting, can be bought from Rabbit Foot Spasm Band on October 13 with atgtickets.com Peerless Pirates and Other Dramas. -

The Sounds of Ideas Forming, Volume 2 Alan Dunn, 22 July 2019

The sounds of ideas forming, Volume 2 Alan Dunn, 22 July 2019 The Crushed This is the Waste Recycling Centre in Bidston, Wirral, and it’s been on my mind a lot recently no matter how I try to forget it. Maybe writing this will clear some of it up - we’ll find out in the last few paragraphs. In 2013 I threw half of my record collection away into those skips. Plastic in one, sleeves in another. I didn’t donate to a charity shop, sell on Discogs, give to a friend nor give to you, dear reader and probable record collector. They aren’t put in storage, but inconceivably crushed. At the time, I probably have around 1,000 discs and make choices to keep about 500. As we are packing to move home quickly, I make two piles and discard those records that have done nothing for me and that I’m sure I won’t listen to again. I reject expensive discs that have let me down with their lack of magic. I get rid of a lot of crap bought in charity shops and shit that I haven’t even listened to more than once. Or not even once. Why think back to it then, if it was only dross that got culled? After getting the vinyl bug back again in 2016, it’s inevitable that I recall those weeks. And since beginning The sounds of idea forming, Volume 2 on Instagram in July 2018, I begin to wonder if my confession may make interesting reading for the community out there, so please stay with me because there are methods behind the madness. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

The Quietus | Features | a Quietus Interview | We Only Have This Excerp

The Quietus | Features | A Quietus Interview | We Only Have This Excerp... http://thequietus.com/articles/07465-mark-e-smith-interview-the-fall News Reviews Features Opinion Film About Us We Only Have This Excerpt: Mark E Smith Of The Fall Interviewed Kevin E.G. Perry , November 24th, 2011 09:29 Mark E Smith has a drink with Kevin EG Perry and tells him about literary influences and Ersatz GB. Photograph by Valerio Berdini Add your comment » 1 of 21 1/4/2012 10:26 AM The Quietus | Features | A Quietus Interview | We Only Have This Excerp... http://thequietus.com/articles/07465-mark-e-smith-interview-the-fall Like Send 544 people like this. “It’s a shopper’s paradise, isn’t it?” says Mark E Smith as he surveys ‘Smoak’, the inexplicably Texan-themed bar in Manchester’s Malmaison hotel. It’s a Saturday afternoon a month or so before Christmas, and both the hotel bar and the adjacent lobby are crawling with families laden with expensive-looking carrier bags. We collect our beers, chosen at random from a long list of imports, and Smith spots a quiet corner on the other side of the lobby: “We’ll go over there.” He moves in a shuffling gait, and already seems older than his 54 years, but his wit and his work rate haven’t slowed. In the 35 years since he and a handful of mates formed The Fall in an apartment in Prestwich he has released 29 albums under that name. Although his bandmates have long since become the subject of regular rotation, over the years Smith has crafted for himself a complex, literate authorial voice which is as unmistakable as his own Salford anti-vocals. -

NEW RELEASE Cds 24/5/19

NEW RELEASE CDs 24/5/19 BLACK MOUNTAIN Destroyer [Jagjaguwar] £9.99 CATE LE BON Reward [Mexican Summer] £9.99 EARTH Full Upon Her Burning Lips £10.99 FLYING LOTUS Flamagra [Warp] £9.99 HAYDEN THORPE (ex-Wild Beasts) Diviner [Domino] £9.99 HONEYBLOOD In Plain Sight [Marathon] £9.99 MAVIS STAPLES We Get By [ANTI-] £10.99 PRIMAL SCREAM Maximum Rock 'N' Roll: The Singles [2CD] £12.99 SEBADOH Act Surprised £10.99 THE WATERBOYS Where The Action Is [Cooking Vinyl] £9.99 THE WATERBOYS Where The Action Is [Deluxe 2CD w/ Alternative Mixes on Cooking Vinyl] £12.99 AKA TRIO (Feat. Seckou Keita!) Joy £9.99 AMYL & THE SNIFFERS Amyl & The Sniffers [Rough Trade] £9.99 ANDREYA TRIANA Life In Colour £9.99 DADDY LONG LEGS Lowdown Ways [Yep Roc] £9.99 FIRE! ORCHESTRA Arrival £11.99 FLESHGOD APOCALYPSE Veleno [Ltd. CD + Blu-Ray on Nuclear Blast] £14.99 FU MANCHU Godzilla's / Eatin' Dust +4 £11.99 GIA MARGARET There's Always Glimmer £9.99 JOAN AS POLICE WOMAN Joanthology [3CD on PIAS] £11.99 JUSTIN TOWNES EARLE The Saint Of Lost Causes [New West] £9.99 LEE MOSES How Much Longer Must I Wait? Singles & Rarities 1965-1972 [Future Days] £14.99 MALCOLM MIDDLETON (ex-Arab Strap) Bananas [Triassic Tusk] £9.99 PETROL GIRLS Cut & Stitch [Hassle] £9.99 STRAY CATS 40 [Deluxe CD w/ Bonus Tracks + More on Mascot]£14.99 STRAY CATS 40 [Mascot] £11.99 THE DAMNED THINGS High Crimes [Nuclear Blast] FEAT MEMBERS OF ANTHRAX, FALL OUT BOY, ALKALINE TRIO & EVERY TIME I DIE! £10.99 THE GET UP KIDS Problems [Big Scary Monsters] £9.99 THE MYSTERY LIGHTS Too Much Tension! [Wick] £10.99 COMPILATIONS VARIOUS ARTISTS Lux And Ivys Good For Nothin' Tunes [2CD] £11.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS Max's Skansas City £9.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS Par Les Damné.E.S De La Terre (By The Wretched Of The Earth) £13.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS The Hip Walk - Jazz Undercurrents In 60s New York [BGP] £10.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS The World Needs Changing: Street Funk.. -

PDF Download Metallica: for Bass Guitar & Vocal: Master of Puppets

METALLICA: FOR BASS GUITAR & VOCAL: MASTER OF PUPPETS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mark Phillips | 54 pages | 01 Dec 1991 | Cherry Lane Music Co ,U.S. | 9780895244086 | English | United States Metallica: For Bass Guitar & Vocal: Master of Puppets PDF Book Email address: optional. With a reputation for drinking, the band stayed sober on recording days. Collector's Guide Publishing. ECW Press. Archived from the original on June 9, Metallica showed up ready to rock, bringing along fully formed demos with fleshed-out arrangements; even their solos were composed. Archived from the original on July 28, Used to contact you regarding your review. With sections performed at beats per minute, it is one of the most intense tracks on the record. All of the songs have been performed live, and some became permanent setlist features. The album revitalized the American underground scene , and inspired similar records by contemporaries. Metal and Hard Rock. Select "Master of Puppets" in the "Filtra" field. And Justice for All as a trilogy over the course of which the band's music progressively matured and became more sophisticated. Retrieved May 16, Master of Puppets peaked at number 29 on the Billboard and received widespread acclaim from critics, who praised its music and political lyrics. He also said that the group was "definitely peaking" at the time and that the album had "the sound of a band really gelling, really learning how to work well together". Retrieved June 12, With bass tablature, standard notation, vocal melody, lyrics, chord names, bass notation legend and introductory text. Duke University Press. Australian Guitar. -

“A Powerful and Thrilling Blend of Punk, Rock, Indie and Hardcore That’Ll Get the Teeth in Your Skull Rattling.” - NME

“a powerful and thrilling blend of punk, rock, indie and hardcore that’ll get the teeth in your skull rattling.” - NME "they're in a field of their own... this is one of the albums of the year" - KERRANG! (5/5) “A debut as savage and unrelenting as their name suggests… the trio are kicking up dust and throwing it in the eyes of all that is inane and boring” - Upset (5/5) "post-punks making the brutal beautiful" - Total Guitar “A distinctive shot at post-hardcore… Brutus contribute an intriguing new voice to underground music” Rocksound “exciting, expansive and full of surprises” - Louder Than War (9/10) “‘Burst’ is a truly stunning record allowing two hostile genres (Punkrock and Postrock) to become real friends with apparent ease” - VISIONS (9/12) "Brutus prove they know exactly what they are doing. With this amazing debut, they deserve to get attention!" - FUZE “..if they were British or American, Brutus would’ve already qualified to grace the covers of Rock Sound and Kerrang!” - Record Collector (4/5) “Short sharp burst of genre-jumping heavy rock” - CMU “With Burst, Brutus claims their unique spot in the Belgian rock-scene. There is no other band that sounds like this trio.” - Damusic “They better start packing for a tour along the world’s biggest metropolises.”- Focus Knack (4/5) “‘Explosive' is the most fitting label for Brutus' debut album - 'Burst' carries masses of energy, catchy hooks and emotional melodies alike.” - Eclipsed (8.5/10) "The trio from Belgium releases an extraordinarily good album on Hassle Records. -

Kick out the Cool Greenhouse Feb 19 2021

Cool Greenhouse w/Kick Out The James Feb 14 2021 www.artguy.com/KOTJ.html www.mixcloud.com/KOTJames The Cool Greenhouse - The End of The World London/The End of the World The Cool Greenhouse - I’m Into C.B. (Fall Cover) RIP Smitty Single The Cool Greenhouse - London London/The End of the World Single The Male Nurse - My Own Private Patrick Swayze The Cool Greenhouse - Life Advice The Cool Greenhouse (album) The Cool Greenhouse - Cardboard Man The Cool Greenhouse (album) The Cool Greenhouse - Dirty Glasses The Cool Greenhouse (album) The Cool Greenhouse - Alexa Single The Desperate Bicycles - Don't Back the Front B-Side to The Medium Was Tedium Wild Billy Childish & The Musicians Of The British Empire - Snack Crack b/w Elvis Presley Is Dead OOPS/ D’oh! The Cool Greenhouse - Dirty Glasses The Cool Greenhouse (album) The Cool Greenhouse - 4Chan The Velvet Underground - There She Goes The Velvet Underground and Nico The Modern Lovers - Pablo Picasso The Cool Greenhouse - Smile, Love The Cool Greenhouse (album) The Cool Greenhouse - Outlines The Cool Greenhouse (album) Greater Than One - Why Do Men Have Nipples? G-Force The Cool Greenhouse - Trojan Horse The Cool Greenhouse (album) Dry Cleaning - Strong Feelings New Long Leg Black Midi - bmbmbm Schlagenheim Uranium Club - Definitely Infrared Radiation Suit The Cosmo Cleaners The Fall - Winter 2 Hex Enduction Hour The Fall - Words of Expectation (Live Peel Session) The Fall - The NWRA Grotesque (After The Gramme) The Fall - Your Heart Out Dragnet The Fall - Fiery Jack Totale's Turns (It's Now Or Never). -

The Fall Free Download

THE FALL FREE DOWNLOAD Albert Camus | 160 pages | 07 May 1991 | Random House USA Inc | 9780679720225 | English | New York, United States About Tomatometer Daisy Drake 7 episodes, Otto Andrew Roussouw When it becomes apparent that a serial killer is on the loose, local detectives must work with Stella to find and capture Paul The Fall, who is attacking young professional women in the city of Belfast. Allan Cubitt. Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Fall band. All the cars in the shots on location at the hospital have steering wheels on the right The Fall of the car, revealing that they are not actually in LA. Error: please try again. Retrieved 2 The Fall Spin : Download as PDF Printable version. Retrieved 26 October Spector talks to Kiera about out-of-body experiences and moves to a psych ward. Brix's tenure in the group marked a shift towards the relatively conventional, with the songs she co-wrote often having strong pop hooks and more orthodox verse-chorus-verse structures. The Con. Perfect for a binge watch and a good chat afterwards. The Vast Abyss. Black Mirror: Season 5. The Quietus. Darkness Visible. Middles, Mick; Smith, Mark E. Real Quick. Smith dead: Eight of The Fall's best tracks ". Get some streaming picks. Watch all you want. Katie enraged at the media treatment of him, decides to take matters into her own hands. Series Info. Retrieved 26 August How did you buy your ticket? Liam Spector 10 episodes, Log in here. The Haunting of Bly Manor. The Belfast Telegraph. Television Without Pity. -

Music 10378 Songs, 32.6 Days, 109.89 GB

Page 1 of 297 Music 10378 songs, 32.6 days, 109.89 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Ma voie lactée 3:12 À ta merci Fishbach 2 Y crois-tu 3:59 À ta merci Fishbach 3 Éternité 3:01 À ta merci Fishbach 4 Un beau langage 3:45 À ta merci Fishbach 5 Un autre que moi 3:04 À ta merci Fishbach 6 Feu 3:36 À ta merci Fishbach 7 On me dit tu 3:40 À ta merci Fishbach 8 Invisible désintégration de l'univers 3:50 À ta merci Fishbach 9 Le château 3:48 À ta merci Fishbach 10 Mortel 3:57 À ta merci Fishbach 11 Le meilleur de la fête 3:33 À ta merci Fishbach 12 À ta merci 2:48 À ta merci Fishbach 13 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 3:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 14 ’¡¢ÁÔé’ 2:29 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 15 ’¡à¢Ò 1:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 16 ¢’ÁàªÕ§ÁÒ 1:36 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 17 à¨éÒ’¡¢Ø’·Í§ 2:07 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 18 ’¡àÍÕé§ 2:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 19 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 4:00 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 20 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:49 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 21 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 22 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡â€ÃÒª 1:58 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 23 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ÅéÒ’’Ò 2:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 24 Ë’èÍäÁé 3:21 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 25 ÅÙ¡’éÍÂã’ÍÙè 3:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 26 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 2:10 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 27 ÃÒËÙ≤˨ђ·Ãì 5:24 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… -

Every Purchase Includes a Free Hot Drink out of Stock, but Can Re-Order New Arrival / Re-Stock

every purchase includes a free hot drink out of stock, but can re-order new arrival / re-stock VINYL PRICE 1975 - 1975 £ 22.00 30 Seconds to Mars - America £ 15.00 ABBA - Gold (2 LP) £ 23.00 ABBA - Live At Wembley Arena (3 LP) £ 38.00 Abbey Road (50th Anniversary) £ 27.00 AC/DC - Live '92 (2 LP) £ 25.00 AC/DC - Live At Old Waldorf In San Francisco September 3 1977 (Red Vinyl) £ 17.00 AC/DC - Live In Cleveland August 22 1977 (Orange Vinyl) £ 20.00 AC/DC- The Many Faces Of (2 LP) £ 20.00 Adele - 21 £ 19.00 Aerosmith- Done With Mirrors £ 25.00 Air- Moon Safari £ 26.00 Al Green - Let's Stay Together £ 20.00 Alanis Morissette - Jagged Little Pill £ 17.00 Alice Cooper - The Many Faces Of Alice Cooper (Opaque Splatter Marble Vinyl) (2 LP) £ 21.00 Alice in Chains - Live at the Palladium, Hollywood £ 17.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Enlightened Rogues £ 16.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Win Lose Or Draw £ 16.00 Altered Images- Greatest Hits £ 20.00 Amy Winehouse - Back to Black £ 20.00 Andrew W.K. - You're Not Alone (2 LP) £ 20.00 ANTAL DORATI - LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA - Stravinsky-The Firebird £ 18.00 Antonio Carlos Jobim - Wave (LP + CD) £ 21.00 Arcade Fire - Everything Now (Danish) £ 18.00 Arcade Fire - Funeral £ 20.00 ARCADE FIRE - Neon Bible £ 23.00 Arctic Monkeys - AM £ 24.00 Arctic Monkeys - Tranquility Base Hotel + Casino £ 23.00 Aretha Franklin - The Electrifying £ 10.00 Aretha Franklin - The Tender £ 15.00 Asher Roth- Asleep In The Bread Aisle - Translucent Gold Vinyl £ 17.00 B.B.