Development and Testing of a Passive Variable-Pitch Propeller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

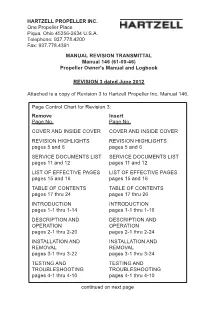

MANUAL REVISION TRANSMITTAL Manual 146 (61-00-46) Propeller Owner's Manual and Logbook

HARTZELL PROPELLER INC. One Propeller Place Piqua, Ohio 45356-2634 U.S.A. Telephone: 937.778.4200 Fax: 937.778.4391 MANUAL REVISION TRANSMITTAL Manual 146 (61-00-46) Propeller Owner's Manual and Logbook REVISION 3 dated June 2012 Attached is a copy of Revision 3 to Hartzell Propeller Inc. Manual 146. Page Control Chart for Revision 3: Remove Insert Page No. Page No. COVER AND INSIDE COVER COVER AND INSIDE COVER REVISION HIGHLIGHTS REVISION HIGHLIGHTS pages 5 and 6 pages 5 and 6 SERVICE DOCUMENTS LIST SERVICE DOCUMENTS LIST pages 11 and 12 pages 11 and 12 LIST OF EFFECTIVE PAGES LIST OF EFFECTIVE PAGES pages 15 and 16 pages 15 and 16 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS pages 17 thru 24 pages 17 thru 26 INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION pages 1-1 thru 1-14 pages 1-1 thru 1-16 DESCRIPTION AND DESCRIPTION AND OPERATION OPERATION pages 2-1 thru 2-20 pages 2-1 thru 2-24 INSTALLATION AND INSTALLATION AND REMOVAL REMOVAL pages 3-1 thru 3-22 pages 3-1 thru 3-24 TESTING AND TESTING AND TROUBLESHOOTING TROUBLESHOOTING pages 4-1 thru 4-10 pages 4-1 thru 4-10 continued on next page Page Control Chart for Revision 3 (continued): Remove Insert Page No. Page No. INSPECTION AND INSPECTION AND CHECK CHECK pages 5-1 thru 5-24 pages 5-1 thru 5-26 MAINTENANCE MAINTENANCE PRACTICES PRACTICES pages 6-1 thru 6-36 pages 6-1 thru 6-38 DE-ICE SYSTEMS DE-ICE SYSTEMS pages 7-1 thru 7-6 pages 7-1 thru 7-6 NOTE 1: When the manual revision has been inserted in the manual, record the information required on the Record of Revisions page in this manual. -

Propeller Aerodynamics CONSTANT-SPEED PROPELLER

Constant-speed propeller Centrifugal twisting force. This is the opposing force to the aerodynamic twist- ing moment. Because this force is greater, it tries to move the blades toward a reduced blade angle. A propeller is designed to withstand the effect of these forces, but the forces are nonetheless important factors in design and operation. The effect of these forces accu- mulates across the length of the blade with the greatest stress at the hub. As the rota- tional speed of the propeller increases, so too do the stresses acting upon it. Given the various forces acting upon a propeller, it is not difficult to understand the serious prob- lem associated with even small nicks or scratches that could weaken the integrity of the propeller. Propeller aerodynamics To understand how a propeller moves an aircraft through the air, it is necessary to look at it from an aerodynamic rather than a mechanical perspective. Figure 5-6 depicts the side view of a propeller detailing the blade path, blade chord, and relative wind. The illustration reveals two types of motion associated with the propeller blades: rota- tional and forward. As a blade moves downward, it simultaneously moves forward. This has a significant effect on the relative wind making it strike the blade at an angle that is between straight ahead and straight down. This angle that the relative wind strikes the blade is called the angle of attack. The relative wind hitting the descending blade is deflected rearward causing the dynamic pressure on the engine side of the blade to be greater than the pressure on the back of the blade. -

DLE-20 Operator’S Manual

DLE-20 Operator’s Manual Specifications Displacement: 20cc [1.2cu. in.] Performance: 2.5HP / 9,000 rpm Idle Speed: 1,700 rpm Ignition Style: Electronic Ignition Recommended Propellers: 14u10, 15 u8, 16u6, 16u8, 17u6 Spark Plug Type: CM6 (Gap) 0.018in.– 0.020 in. [0.45mm –0.51mm] Diameter × Stroke: 1.26in. [32mm] u0.98in. [25 mm] Compression Ratio: 10.5 :1 Carburetor: DLE MP 148 100424 with Manual Choke Weight: Main Engine − 1.43 lb [650g] Muffler − 1.76 oz [50 g] Electronic Ignition − 4.23oz [120 g] ™ Fuel: 87− 93 Octane Gasoline with a 30:1 gas/2-stroke (2-cycle) oil mixture 1 © 2010 Hobbico®, Inc. DLEG0020 Mnl Parts List (1) DLE-20cc Gas Engine w/DLE MP 148 100424 (1) DLE Spark Plug (NGK CM6 size) with additional spring (1) Muffl er with gasket (2) 4 x 14 mm SHCS (muffl er mounting) (1) Electronic Ignition Module with additional tachometer lead (1) Silicone Pick-up Wire Cover / Ignition Wire Cover (1) Red Three Pin Connector Lead with Pig Tail (ignition switch) (1) Long Throttle Arm Extension with installation screw and nut (2) Three Pin Connector Securing Clips (1) DLE Decal (not pictured) Safety Tips and Warnings ● This engine is not a toy. Please place your safety and the safety of others paramount while operating. DLE will not be held responsible for any safety issues or accidents involving this engine. ● Operate the engine in a properly ventilated area. ● Before starting the engine, please make sure all components including the propeller and the engine mount are secure and tight. -

Propeller Operation and Malfunctions Basic Familiarization for Flight Crews

PROPELLER OPERATION AND MALFUNCTIONS BASIC FAMILIARIZATION FOR FLIGHT CREWS INTRODUCTION The following is basic material to help pilots understand how the propellers on turbine engines work, and how they sometimes fail. Some of these failures and malfunctions cannot be duplicated well in the simulator, which can cause recognition difficulties when they happen in actual operation. This text is not meant to replace other instructional texts. However, completion of the material can provide pilots with additional understanding of turbopropeller operation and the handling of malfunctions. GENERAL PROPELLER PRINCIPLES Propeller and engine system designs vary widely. They range from wood propellers on reciprocating engines to fully reversing and feathering constant- speed propellers on turbine engines. Each of these propulsion systems has the similar basic function of producing thrust to propel the airplane, but with different control and operational requirements. Since the full range of combinations is too broad to cover fully in this summary, it will focus on a typical system for transport category airplanes - the constant speed, feathering and reversing propellers on turbine engines. Major propeller components The propeller consists of several blades held in place by a central hub. The propeller hub holds the blades in place and is connected to the engine through a propeller drive shaft and a gearbox. There is also a control system for the propeller, which will be discussed later. Modern propellers on large turboprop airplanes typically have 4 to 6 blades. Other components typically include: The spinner, which creates aerodynamic streamlining over the propeller hub. The bulkhead, which allows the spinner to be attached to the rest of the propeller. -

Comparison of Helicopter Turboshaft Engines

Comparison of Helicopter Turboshaft Engines John Schenderlein1, and Tyler Clayton2 University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, 80304 Although they garnish less attention than their flashy jet cousins, turboshaft engines hold a specialized niche in the aviation industry. Built to be compact, efficient, and powerful, turboshafts have made modern helicopters and the feats they accomplish possible. First implemented in the 1950s, turboshaft geometry has gone largely unchanged, but advances in materials and axial flow technology have continued to drive higher power and efficiency from today's turboshafts. Similarly to the turbojet and fan industry, there are only a handful of big players in the market. The usual suspects - Pratt & Whitney, General Electric, and Rolls-Royce - have taken over most of the industry, but lesser known companies like Lycoming and Turbomeca still hold a footing in the Turboshaft world. Nomenclature shp = Shaft Horsepower SFC = Specific Fuel Consumption FPT = Free Power Turbine HPT = High Power Turbine Introduction & Background Turboshaft engines are very similar to a turboprop engine; in fact many turboshaft engines were created by modifying existing turboprop engines to fit the needs of the rotorcraft they propel. The most common use of turboshaft engines is in scenarios where high power and reliability are required within a small envelope of requirements for size and weight. Most helicopter, marine, and auxiliary power units applications take advantage of turboshaft configurations. In fact, the turboshaft plays a workhorse role in the aviation industry as much as it is does for industrial power generation. While conventional turbine jet propulsion is achieved through thrust generated by a hot and fast exhaust stream, turboshaft engines creates shaft power that drives one or more rotors on the vehicle. -

Aircraft Service Manual

Propeller Technical Manual Jabiru Aircraft Pty Ltd JPM0001-1 4A482U0D And 4A484E0D Propellers Propeller Technical Manual FOR 4A482U0D and 4A484E0D Propellers DOCUMENT No. JPM0001-1 DATED: 1st Feb 2013 This Manual has been prepared as a guide to correctly operate & maintain Jabiru 4A482U0D and 4A484E0D propellers. It is the owner's responsibility to regularly check the Jabiru web site at www.jabiru.net.au for applicable Service Bulletins and have them implemented as soon as possible. Manuals are also updated periodically with the latest revisions available from the web site. Failure to maintain the propeller, engine or aircraft with current service information may render the aircraft un-airworthy and void Jabiru’s Limited, Express Warranty. This document is controlled while it remains on the Jabiru server. Once this no longer applies the document becomes uncontrolled. Should you have any questions or doubts about the contents of this manual, please contact Jabiru Aircraft Pty Ltd. This document is controlled while it remains on the Jabiru server. Once this no longer applies the document becomes uncontrolled. ISSUE 1 Dated : 1st Feb 2013 Issued By: DPS Page: 1 of 32 L:\files\Manuals_For_Products\Propeller_Manuals\JPM0001-1_Prop_Manual (1).doc Propeller Technical Manual Jabiru Aircraft Pty Ltd JPM0001-1 4A482U0D And 4A484E0D Propellers 1.1 TABLE OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................................. -

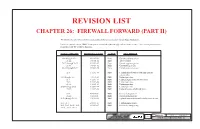

Chapter 26: Firewall Forward (Part Ii)

REVISION LIST CHAPTER 26: FIREWALL FORWARD (PART II) The following list of revisions will allow you to update the Legacy construction manual chapter listed above. Under the “Action” column, “R&R” directs you to remove and replace the pages affected by the revision. “Add” directs you to insert the pages shows and “R” to remove the pages. PAGE(S) AFFECTED REVISION # & DATE ACTION DESCRIPTION 26-1 through 26-21 0/02-15-02 None Current revision is correct 26-22 1/09-18-02 R&R Text Correction 26-23 through 26-32 0/02-15-02 None Current revision is correct 26-33 1/09-18-02 R&R Corrected Fig. 26:H:1 26-34 through 26-35 0/02-15-02 None Current revision is correct 26-1 3/12-15-04 R&R Updated table of contents with page numbers and part nbrs. 26-2 through 26-3 3/12-15-04 R&R Updated part nbrs. 26-4 3/12-15-04 R&R Updated engine isolator kit information. 26-6 3/12-15-04 R&R Updated part nbrs. 26-18 3/12-15-04 R&R Updated part nbrs. 26-20 through 26-21 3/12-15-04 R&R Updated part nbrs. 26-26 3/12-15-04 R&R Updated location of bulkhead fitting. 26-3 4/09/30/06 R&R Corrected plug part nbr. 26-26 4/09/30/06 R&R Corrected plug part nbr. 26-27 through 26-33 4/09-30-06 R&R Updated hose numbers and bolded so easier to read. -

Comparison of Helicopter Engines

Comparison of Helicopter Engines John Schenderlein, Tyler Clayton Turboshafts...What are they? • Needed for high power in a small envelope • Very similar to turboprops • many turboshafts derived from turboprop engines • However, • exhaust is not used to propel • propeller load is applied to the airframe • Began ~1950s Main Uses • Helicopters • APUs • Marine Vehicles CH-53 Super Stallion • Tanks • Motorcycles • industrial power generation M1 Abrams MTT Superbike Major Players in the Market Turbomeca • French Manufacturer for small/medium turboshafts (500-3000 shp) • 18000+ in operation • Most popular engine: Arriel (600-1000 shp) • 30 variants • 245 lbs • SFC = 0.57 • 1 axial/1 Centrifugal compressor (PR ~9) • 2 HPT/1 FPT turbine Turbomeca • Newest Engine: Arrano (2018) • 10-15% increase SFC • new thermodynamic core & use of variable pitch inlet guide blades • Uses additive manufacturing for injectors Rolls-Royce • Most popular engine: M250 Series • inherited from Allison Engine Company (1990s) • 31000+ produced (50%+ in operation) • 450-715 shp • 160-275 lbs • 4-6 axial/1 centrifugal compressor (PR 6-9) • 2 HPT/2 FPT • Also used on the MTT Superbike RQ-8A Fire Scout Allison Engines (Rolls Royce) • Most noteable engine: T406 • Build specifically for the V-22 Osprey • 6150 shp • 971 lbs (6.33 p/w) • 14 axial compressor stages! Pratt and Whitney Canada • Canadian based subsidiary of PW • focuses on smaller aircraft engines • Majority of their engines based on the PT6 turboprop • PT6B/C series and the PT6T Twin-Pac (1000-2000 shp) • 3-4 axial/1 -

Helicopter Turboshafts

Helicopter Turboshafts Luke Stuyvenberg University of Colorado at Boulder Department of Aerospace Engineering The application of gas turbine engines in helicopters is discussed. The work- ings of turboshafts and the history of their use in helicopters is briefly described. Ideal cycle analyses of the Boeing 502-14 and of the General Electric T64 turboshaft engine are performed. I. Introduction to Turboshafts Turboshafts are an adaptation of gas turbine technology in which the principle output is shaft power from the expansion of hot gas through the turbine, rather than thrust from the exhaust of these gases. They have found a wide variety of applications ranging from air compression to auxiliary power generation to racing boat propulsion and more. This paper, however, will focus primarily on the application of turboshaft technology to providing main power for helicopters, to achieve extended vertical flight. II. Relationship to Turbojets As a variation of the gas turbine, turboshafts are very similar to turbojets. The operating principle is identical: atmospheric gases are ingested at the inlet, compressed, mixed with fuel and combusted, then expanded through a turbine which powers the compressor. There are two key diferences which separate turboshafts from turbojets, however. Figure 1. Basic Turboshaft Operation Note the absence of a mechanical connection between the HPT and LPT. An ideal turboshaft extracts with the HPT only the power necessary to turn the compressor, and with the LPT all remaining power from the expansion process. 1 of 10 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics A. Emphasis on Shaft Power Unlike turbojets, the primary purpose of which is to produce thrust from the expanded gases, turboshafts are intended to extract shaft horsepower (shp). -

Energy Conversion and Efficiency in Turboshaft Engines

E3S Web of Conferences 85, 01001 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20198501001 EENVIRO 2018 Energy conversion and efficiency in turboshaft engines Cristian Dobromirescu1, and Valeriu Vilag1,* 1 Research and development institute for gas turbines COMOTI, Aviation and industrial turbines. Gas-turbines assembly department, 220 D Iuliu Maniu Bd., sector 6, Bucharest Romania Abstract. This paper discusses the methods of energy conversion in a turboshaft engine. Those methods cover the thermodynamic cycle and the engine performances, the possible energy sources and their impact on environment as well as the optimal solutions for maximum efficiency in regards to turbine design and application. The paper also analyzes the constructive solutions that limit the efficiency and performances of turboshaft engines. For the purpose of this paper a gas-turbine design task is performed on an existing engine to appreciate the methods presented. In the final part of this paper it is concluded that in order to design an engine it is necessary to balance the thermodynamic aspects, for maximum efficiency, and the constructive elements, so that the engine can be manufactured. − Pressure. 1 Introduction The source of energy for the engine is the fuel. For the combustion to take place in optimal conditions, or at Since the creation of the first internal combustion engine all at high altitudes, it is necessary to increase the it is a top priority to use as much energy and as pressure of the intake air through a compressor. The efficiently as possible [1]. Thus, the study of energy compressor consumes work and increases the potential conversion and energy efficiency is very important and energy of the air by raising its pressure. -

The Applicability of Electrically Driven Accessories for Turboshaft Engines

E AMEICA SOCIEY O MECAICA EGIEES G 4 E. 4 S., Yr, .Y. 00 e Sociey sa o e esosie o saemes o oiios aace i aes o iscussio a meeigs o e Sociey o o is iisios o Secios, m ® o ie i is uicaios. iscussio is ie oy i e ae is u ise i a ASME oua. aes ae aaiae om ASME o mos ae e meeig. ie i U.S.A. Copyright © 1993 by ASME h Applblt f Eltrll rvn Ar fr rbhft Enn Downloaded from http://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/GT/proceedings-pdf/GT1993/78910/V03BT16A069/2403672/v03bt16a069-93-gt-313.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 M. Simon Jarvis Warren J. Ostergren General Electric Aircraft Engines Lynn, Massachusetts Bert Smith Aviation Applied Technology Directorate U. S. Army Aviation and Troop Command Fort Eustis, Virginia Abstract more detailed description of the electric accessories and the engine Improved electrical power generation and actuation systems mounting, and electronics cooling considerations. Given the pre- offer new design approaches for performing the engine control and liminary design of an electric system, a trade study was completed accessory functions in helicopter propulsion systems. Present and the results are presented with a summary of the hardware helicopter technology utilizes turboshaft engines with mechanically experience. driven accessories. These accessories perform the functions of starting, fuel and lube pumping, variable stator actuation and inlet particle separation. This paperdiscusses the applicability of replacing Current Accessory Systems the mechanically driven accessories with their electrically driven Present gas turbine aircraft engines require control and accessory counterparts. -

Gas Turbine Engine Starting Applicated on TV2-117 Turboshaft

Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research Vol. 7, No. 5, 2017, 2005-2009 2005 Gas Turbine Engine Starting Applicated on TV2-117 Turboshaft Razvan Marius Catana Grigore Cican Gabriel Dediu Gas Turbine Experimentation Aerospace Sciences Gas Turbine Experimentation Complex, RR&DI for Gas Turbines “Elie Carafoli” Department Complex, RR&DI for Gas Turbines Comoti Politehnica University of Bucharest Comoti Bucharest, Romania Bucharest, Romania Bucharest, Romania [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—The paper presents the examination of two different rotor of the free power turbine. The gas generator consists of types of engine starting configurations, applicated on TV2-117A nine stage axial compressor, of which four stator stages are turboshaft, running into the test bench. The first type of starting with variable geometry, an annular combustion chamber and configuration is a normal starting, with the engine connected to two stage axial turbines. The power turbine is also an axial the dynamometer which controls the free turbine speed by the turbine, consisting of two stages, which is controlled by a speed dynamometer load. The second type of starting is a different one, regulator. The free power turbine speed regulator maintains the engine is not connected with the dynamometer, therefore it constant the free power turbine speed, by fuel control, in results that there is no control of the free turbine speed from the connection with the engine main fuel pump. In the starting dynamometer, only from the engine but in particular conditions. phase the free power turbine speed regulator is a hydro To achieve the starting phase an instrumentation scheme is mechanical speed controller that ensures the free power turbine created, to control and monitor the engine, and a starting sequence with all the parameters, confirmations and commands not to over speed.