Bryan R. Just

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edwin M. Shook Archival Collection, Guatemala City, Guatemala

FAMSI © 2004: Barbara Arroyo and Luisa Escobar Edwin M. Shook Archival Collection, Guatemala City, Guatemala Research Year: 2003 Culture: Maya Chronology: Pre-Classic to Post Classic Location: Various archaeological sites in Guatemala and México Site: Tikal, Uaxactún, Copán, Mayapán, Kaminaljuyú, Piedras Negras, Palenque, Ceibal, Chichén Itzá, Dos Pilas Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Background Project Priorities Conservation Issues Guide to the Edwin M. Shook Archive Site Records Field Notes Photographs Correspondence and Documents Illustrations Maps Future Work Acknowledgments List of Figures Sources Cited Abstract The Edwin M. Shook archive is a collection of documents that resulted from Dr. Edwin M. Shook’s archaeological fieldwork in Mesoamerica from 1934-1998. He came to Guatemala as part of the Carnegie Institution and carried out investigations at various sites including Tikal, Uaxactún, Copán, Mayapán, among many others. He further established his residence in Guatemala where he continued an active role in archaeology. The archive donated by Dr. Shook to Universidad del Valle de Guatemala in 1998 contains his field notes, Guatemala archaeological site records, photographs, documents, and illustrations. They were stored at the Department of Archaeology for several years until we obtained FAMSI’s support to start the conservation and protection of the archive. Basic conservation techniques were implemented to protect the archive from further damage. This report lists several sets of materials prepared by Dr. Shook throughout his fieldwork experience. Through these data sets, people interested in Shook’s work can know what materials are available for study at the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala. Resumen El archivo Edwin M. Shook consiste en una colección de documentos que resultaron de las investigaciones arqueológicas en Mesoamérica realizadas por el Dr. -

With the Protection of the Gods: an Interpretation of the Protector Figure in Classic Maya Iconography

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography Tiffany M. Lindley University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Lindley, Tiffany M., "With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2148. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2148 WITH THE PROTECTION OF THE GODS: AN INTERPRETATION OF THE PROTECTOR FIGURE IN CLASSIC MAYA ICONOGRAPHY by TIFFANY M. LINDLEY B.A. University of Alabama, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 © 2012 Tiffany M. Lindley ii ABSTRACT Iconography encapsulates the cultural knowledge of a civilization. The ancient Maya of Mesoamerica utilized iconography to express ideological beliefs, as well as political events and histories. An ideology heavily based on the presence of an Otherworld is visible in elaborate Maya iconography. Motifs and themes can be manipulated to convey different meanings based on context. -

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

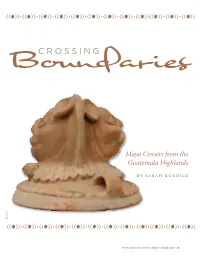

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

Extension and Renomination of the “Ancient Maya City of Calakmul, Campeche”)

LATIN AMERICA / CARIBBEAN ANCIENT MAYA CITY AND PROTECTED FORESTS OF CALAKMUL, CAMPECHE (Extension and renomination of the “Ancient Maya City of Calakmul, Campeche”) MEXICO Mexico – Ancient Maya City and Protected Tropical Forests of Calakmul WORLD HERITAGE NOMINATION – IUCN TECHNICAL EVALUATION ANCIENT MAYA CITY AND PROTECTED TROPICAL FORESTS OF CALAKMUL, CAMPECHE (MEXICO) – ID 1061 Bis IUCN RECOMMENDATION TO WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: To defer the nomination. Key paragraphs of Operational Guidelines: Paragraph 77: Nominated property has the potential to meet World Heritage criteria. Paragraph 78: Nominated property does not meet integrity or protection and management requirements. Background note: The Ancient Maya City of Calakmul, Campeche was inscribed under cultural criteria (i), (ii), (iii), and (iv) in 2002. The cultural property is 3,000 hectares (ha) in size with a buffer zone of 147,195 ha. This is a renomination and extension of the existing Ancient Maya City as a mixed site. 1. DOCUMENTATION Biosfera de Calakmul. Contrato CONAP A-P-VO2- RBCA-FDS-11. Gobierno de México (May, 1989). a) Date nomination received by IUCN: 20 March 2013 DECRETO por el que se declara la Reserva de la biosfera Calakmul, ubicada en los Municipios de b) Additional information officially requested from Champotón y Hopelchem, Camp. Parks Watch Mexico and provided by the State Party: No supplementary (Undated). Profile: Calakmul Biosphere Reserve. information was formally requested by IUCN, however Ramón Pérez Gil Salcido, et al (2003). Evaluación the State Party submitted additional information on 26 Independiente SINAP I. Report to the Mexican Fund February 2014 following dialogue between the State for the Conservation of Nature. -

Polities and Places: Tracing the Toponyms of the Snake Dynasty

Polities and Places: Tracingthe Toponymsof the Snake Dynasty SIMON MARTIN University of Pennsylvania Museum ERIK VELÁSQUEZ GARCÍA Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México One of the more intriguing and important topics to thonous ones that had at some point transferred their emerge in Maya studies of recent years has been the his- capitals or splintered, each faction laying claim to the tory of the “Snake” dynasty. Research over the past two same title. The landscape of the Classic Maya proves decades has identified mentions of its kings across the to have been a volatile one, not simply in the dynamic length and breadth of the lowlands and produced evi- interactions and imbalances of power between polities, dence that they were potent political players for almost but in the way the polities themselves were shaped by two centuries, spanning the Early Classic to Late Classic historical forces through time. periods.1 Yet this data has implications that go beyond a single case study and can be used to address issues of general relevance to Classic Maya politics. In this brief Placing Calakmul paper we use them to further explore the meaning of The distinctive Snake emblem glyphs and their connection to polities and emblem glyph is ex- places. pressed in full as K’UH- The significance of emblem glyphs—whether they ka-KAAN-la-AJAW or are indicative of cities, deities, domains, polities, or k’uhul kaanul ajaw (Fig- dynasties—has been debated since their discovery ure 1).3 It first came to (Berlin 1958). The recognition of their role as the scholarly notice as one personal epithets of kings based on the title ajaw “lord, of the “four capitals” ruler” (Lounsbury 1973) was the essential first step to listed on Copan Stela A, comprehension (Mathews and Justeson 1984; Mathews a set of cardinally affili- Figure 1. -

Archaeological Reconnaissance in Southeastern Campeche, México

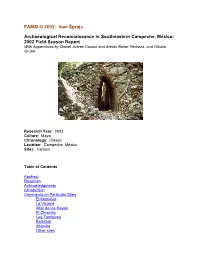

FAMSI © 2003: Ivan Šprajc Archaeological Reconnaissance in Southeastern Campeche, México: 2002 Field Season Report With Appendices by Daniel Juárez Cossío and Adrián Baker Pedroza, and Nikolai Grube Research Year: 2002 Culture: Maya Chronology: Classic Location: Campeche, México Sites: Various Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Acknowledgments Introduction Comments on Particular Sites El Mameyal La Victoria Altar de los Reyes El Chismito Los Tambores Balakbal Altamira Other sites Concluding Remarks List of Figures Appendix 1: Emergency consolidation works at Mucaancah by Daniel Juárez Cossío and Adrián Baker Pedroza Appendix 2: Epigraphic Analysis of Altar 3 of Altar de los Reyes by Nikolai Grube Sources Cited Abstract The project represented the fourth season of reconnaissance works in an archaeologically little known region of central Maya Lowlands. Several formerly unknown archaeological sites were surveyed in the southeastern part of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve and in the adjacent region to the east, and two large sites reported by Karl Ruppert’s expeditions in 1930s were reexamined. The location and basic characteristics of the sites, mainly pertaining to the Classic period, were recorded and some surface pottery was collected. At Altar de los Reyes, a major urban center, two main architectural complexes were mapped and some interesting sculpted monuments were found, including an extraordinary altar with a series of emblem glyphs. Resumen El proyecto representó la cuarta temporada de trabajos de reconocimiento en una región arqueológicamente poco conocida de las tierras bajas mayas centrales. Inspeccionamos varios sitios arqueológicos previamente desconocidos en la parte sureste de la Reserva de la Biósfera de Calakmul y en la región adyacente hacia el este, y reexaminamos dos sitios grandes reportados por las expediciones de Karl Ruppert en la década de 1930. -

Prehistoric Human-Environment Interactions in the Southern Maya Lowlands: the Holmul Region Case

Prehistoric Human-Environment Interactions in the Southern Maya Lowlands: The Holmul Region Case Final Report to the National Science Foundation 2010 Submitted by: Francisco Estrada-Belli and David Wahl Introduction Dramatic population changes evident in the Lowland Maya archaeological record have led scholars to speculate on the possible role of environmental degradation and climate change. As a result, several paleoecological and geochemical studies have been carried out in the Maya area which indicate that agriculture and urbanization may have caused significant forest clearance and soil erosion (Beach et al., 2006; Binford et al., 1987; Deevey et al., 1979; Dunning et al., 2002; Hansen et al., 2002; Jacob and Hallmark, 1996; Wahl et al., 2007). Studies also indicate that the late Holocene was characterized by centennial to millennial scale climatic variability (Curtis et al., 1996; Hodell et al., 1995; Hodell et al., 2001; Hodell et al., 2005b; Medina-Elizalde et al., 2010). These findings reinforce theories that natural or anthropogenically induced environmental change contributed to large population declines in the southern Maya lowlands at the end of the Preclassic (~A.D. 200) and Classic (~A.D. 900) periods. However, a full picture of the chronology and causes of environmental change during the Maya period has not emerged. Many records are insecurely dated, lacking from key cultural areas, or of low resolution. Dating problems have led to ambiguities regarding the timing of major shifts in proxy data (Brenner et al., 2002; Leyden, 2002; Vaughan et al., 1985). The result is a variety of interpretations on the impact of observed environmental changes from one site to another. -

The Terminal Classic Period at Ceibal and in the Maya Lowlands

THE TERMINAL CLASSIC PERIOD AT CEIBAL AND IN THE MAYA LOWLANDS Takeshi Inomata and Daniela Triadan University of Arizona Ceibal is well known for the pioneering investigations conducted by Harvard University in the 1960s (Sabloff 1975; Smith 1982; Tourtellot 1988; Willey 1990). Since then, Ceibal has been considered to be a key site in the study of the Classic Maya collapse (Sabloff 1973a, 1973b; Sabloff and Willey 1967). The results of this project led scholars to hypothesize the following: 1) Ceibal survived substantially longer than other centers through the period of the Maya collapse; and 2) the new styles of monuments and new types of ceramics resulted from foreign invasions, which contributed to the Maya collapse. In 2005 we decided to revisit this important site to re-examine these questions in the light of recent developments in Maya archaeology and epigraphy. The results of the new research help us to shape a more refined understanding of the political process during the Terminal Classic period. The important points that we would like to emphasize in this paper are: 1) Ceibal did not simply survive through this turbulent period, but it also experienced political disruptions like many other centers; 2) this period of political disruptions was followed by a revival of Ceibal; and 3) our data support the more recent view that there were no foreign invasions; instead the residents of Ceibal were reorganizing and expanding their inter-regional networks of interaction. Ceibal is located on the Pasión River, and a comparison with the nearby Petexbatun centers, including Dos Pilas and Aguateca, is suggestive. -

Installments 1-10

ThePARIJournal A quarterly publication of the Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute Volume XIII, No. IV, Summer 2013 The Further Adventures of Merle1 MERLE GREENE ROBERTSON In This Issue: The Further Adventures of Merle by Merle Greene Robertson PAGES 1-7 • A Late Preclassic Distance Number by Mario Giron-Ábrego PAGES 8-12 Joel Skidmore Editor [email protected] Marc Zender Associate Editor [email protected] Figure 1. On the Usumacinta River on the way to Yaxchilan, 1965. The PARI Journal 202 Edgewood Avenue “No! You can’t go into the unknown wilds birds, all letting each other know where San Francisco, CA 94117 of Alaska!” That statement from my moth- they are. Evening comes early—dark by 415-664-8889 [email protected] er nearly 70 years ago is what changed my four o’clock. Colors are lost in pools of life forever. I went to Mexico instead, at darkness. Now the owls are out lording it Electronic version that time almost as unknown to us in the over the night, lucky when you see one. available at: U.S. as Alaska. And then later came the But we didn’t wait for nightfall to www.mesoweb.com/ pari/journal/1304 jungle, the jungle of the unknown that I pitch our camp. Champas made for our loved, no trails, just follow the gorgeous cooking, champas for my helpers, and a guacamayos in their brilliant red, yellow, ISSN 1531-5398 and blue plumage, who let you know where they are before you see them, by 1 Editor’s note: This memoir—left untitled by their constant mocking “clop, clop, clop.” the author—was completed in 2010, in Merle’s 97th Mahogany trees so tall you wonder if, year. -

Codex Aubin: History in Reprint Arjun Sai Krishnan

Codex Aubin: History in Reprint Arjun Sai Krishnan I. Introduction The Codex Aubin, a post-conquest Nahuatl-language pictorial codex, is a valuable record of indigenous perspectives on historiography in the period immediately succeeding the Spanish conquest of the Valley of Mexico. A fascinating handwritten account of Mexica (Aztec) history and legend, it begins with a departure from Áztlan, the mythical homeland of the Mexica, and ending in the early seventeenth century with a depiction of indigenous life in early colonial Mexico. Clearly drawing from the Aztec cartographic and pictorial tradition, the codex contains primarily Nahuatl text transcribed in Roman script and printed on colonial octavo paper (Paxton & Cicero, 2017). The text represents a complex intersection of cultures, languages, and representational systems: an indigenous annal swathed in European conventions, unravelling the many competing traditions encompassed in the codex grants a unique window into the status of language and history in the nascent mestizo society of Mexico. A number of scholars have commented on the codex’s historiography (Rajagopalan, 2019), (Navarrete, 2000), most focusing on a subset of the original text’s narratorial and pictorial choices. An exploration of the tlacuilo’s intentions and audience becomes key; we see the creative re-telling of an ancient myth, illustrated with traditional imagery but written in Roman script and glossed in Spanish. What emerges is a clear picture of a cultural encounter; the Aubin codex is a demonstrative example of the post-Conquest European reformulation of indigenous conventions. This work will attempt to review some of the scholarship surrounding the Aubin codex, but most interestingly, we will also focus on the Princeton University manuscript copy of the codex. -

La Nueva Historia De La Puerta a Las Tierras Bajas: Descubrimientos Recientes Sobre La Interacción, Arqueología Y Epigrafía De Cancuen

Demarest, Arthur, Tomás Barrientos, Melanie Forné, Marc Wolf y Ronald Bishop 2008 La nueva historia de la puerta a las Tierras Bajas: Descubrimientos recientes sobre la interacción, arqueología y epigrafía de Cancuen. En XXI Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2007 (editado por J.P. Laporte, B. Arroyo y H. Mejía), pp.713-729. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala (versión digital). 44 LA NUEVA HISTORIA DE LA PUERTA A LAS TIERRAS BAJAS: DESCUBRIMIENTOS RECIENTES SOBRE LA INTERACCIÓN, ARQUEOLOGÍA Y EPIGRAFÍA DE CANCUEN Arthur Demarest Tomas Barrientos Melanie Forné Marc Wolf Ronald Bishop Proyecto Arqueológico Cancuen Palabras clave Arqueología Maya, Petén, río Pasión, patrón de asentamiento, Cancuen, El Raudal, Tres Islas, registro de sitios, ruta Altiplano-Tierras Bajas, gobernante Taj Chan Ahk Abstract THE NEW HISTORY OF THE GATEWAY TO THE LOWLANDS: RECENT DISCOVERIES ON THE INTERACTION, ARCHAEOLOGY, AND EPIGRAPHY AT CANCUEN Investigations at Cancuen have been a series of surprises. The general interpretations for exchange, production, alliances, and history at Cancuen have changed each year. Now we know that the site did not begin as a commercial center but as a small outpost. A century later it converted itself into a rich and important center due to the collapse of centers to the North. This work will describe the new evidence that Cancuen’s apogee was due to elite and artisan immigrants from the North, who combined forces with King Taj Chan Ahk in the wars, alliances, and workshop production of his kingdom. It seems that these elite immigrants also brought with them the disorder and chaos of the collapse of the kingdoms upriver.