Formatted Dissertation Revised

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide Represents the Most Requested Songs at Weddings and Parties

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide represents the most requested songs at Weddings and Parties. Please circle songs you like and cross out the ones you don’t. You can also write-in additional requests on the back page! WEDDING SONGS ALL TIME PARTY FAVORITES CEREMONY MUSIC CELEBRATION THE TWIST HERE COMES THE BRIDE WE’RE HAVIN’ A PARTY SHOUT GOOD FEELIN’ HOLIDAY THE WEDDING MARCH IN THE MOOD YMCA FATHER OF THE BRIDE OLD TIME ROCK N ROLL BACK IN TIME INTRODUCTION MUSIC IT TAKES TWO STAYIN ALIVE ST. ELMOS FIRE, A NIGHT TO REMEMBER, RUNAROUND SUE MEN IN BLACK WHAT I LIKE ABOUT YOU RAPPERS DELIGHT GET READY FOR THIS, HERE COMES THE BRIDE BROWN EYED GIRL MAMBO #5 (DISCO VERSION), ROCKY THEME, LOVE & GETTIN’ JIGGY WITH IT LIVIN, LA VIDA LOCA MARRIAGE, JEFFERSONS THEME, BANG BANG EVERYBODY DANCE NOW WE LIKE TO PARTY OH WHAT A NIGHT HOT IN HERE BRIDE WITH FATHER DADDY’S LITTLE GIRL, I LOVED HER FIRST, DADDY’S HANDS, FATHER’S EYES, BUTTERFLY GROUP DANCES KISSES, HAVE I TOLD YOU LATELY, HERO, I’LL ALWAYS LOVE YOU, IF I COULD WRITE A SONG, CHICKEN DANCE ALLEY CAT CONGA LINE ELECTRIC SLIDE MORE, ONE IN A MILLION, THROUGH THE HANDS UP HOKEY POKEY YEARS, TIME IN A BOTTLE, UNFORGETTABLE, NEW YORK NEW YORK WALTZ WIND BENEATH MY WINGS, YOU LIGHT UP MY TANGO YMCA LIFE, YOU’RE THE INSPIRATION LINDY MAMBO #5BAD GROOM WITH MOTHER CUPID SHUFFLE STROLL YOU RAISE ME UP, TIMES OF MY LIFE, SPECIAL DOLLAR WINE DANCE MACERENA ANGEL, HOLDING BACK THE YEARS, YOU AND CHA CHA SLIDE COTTON EYED JOE ME AGAINST THE WORLD, CLOSE TO YOU, MR. -

Felix Issue 0985, 1994

loo<tF The Student Newspaper of Imperiaiperiall ColleqCollegee I 3DRI8B3iaCE||olrj g 210CT94 TCCB-tSCTIONj enamings benefits of the proposal had not. ANDREW DORMAN-SMITH been adequately debated. Professor Shaw said the name of Senior academics at. the. the Department itself does not Department, of Mineral Resources overly matter, and said he was, Engineering (MRE) have called "a believer in tradition". Professor for further discussions over a plan Shaw would not say if he sup- to rename the department. Earth ported the name change proposal. Resources Engineering has However, the new head of emerged as the favourite choice MRE, and Dean of the newly for a new name, after discussions established Graduate School of between college officials. the Environment, Professor The change has been mooted Woods, is believed to think the following a letter from the proposal is a 'great idea'. His role Professor John Archer, Pro- as Dean will be to coordinate the Rector, which asks for comments departments of Imperial, and to on the new title. Professor Archer, present the benefits for research said that he has received only one of the college in line with a review negative response to his letter, completed in May by Sir John and claimed that most of the Mason. department's staff agree with the The other two RSM depart- proposal. But Professor Archer ments may also change names. said discussions are continuing - The college's chief decision mak- despite the publication of an offi- ing body, the Management cial college note which says the Finnish Embassy Planning Group (MPG), has sug- Photo by Ivan Chan change will take place "shortly". -

Music 18145 Songs, 119.5 Days, 75.69 GB

Music 18145 songs, 119.5 days, 75.69 GB Name Time Album Artist Interlude 0:13 Second Semester (The Essentials Part ... A-Trak Back & Forth (Mr. Lee's Club Mix) 4:31 MTV Party To Go Vol. 6 Aaliyah It's Gonna Be Alright 5:34 Boomerang Aaron Hall Feat. Charlie Wilson Please Come Home For Christmas 2:52 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Holy Night 4:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Christmas Song 4:20 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! 2:22 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville White Christmas 4:48 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Such A Night 3:24 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Little Town Of Bethlehem 3:56 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Silent Night 4:06 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Louisiana Christmas Day 3:40 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Star Carol 2:13 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Bells Of St. Mary's 2:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:42 Billboard Top R&B 1967 Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:41 Classic Soul Ballads: Lovin' You (Disc 2) Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven 4:38 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville I Owe You One 5:33 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight 4:24 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville My Brother, My Brother 4:59 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Betcha By Golly, Wow 3:56 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Song Of Bernadette 4:04 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville You Never Can Tell 2:54 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Bells 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville These Foolish Things 4:23 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Roadie Song 4:41 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Ain't No Way 5:01 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Grand Tour 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Lord's Prayer 1:58 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:43 Smooth Grooves: The 60s, Volume 3 L.. -

Beverly Hills

briefs • City to subsidize $1.6 million briefs • City refuses to declare rudy cole • My recommendations loan for City Manager housing Page 3 opinion on subway route Page 4 for state office Page 6 ALSO ON THE WEB Beverly Hills www.bhweekly.com WeeklySERVING BEVERLY HILLS • BEVERLYWOOD • LOS ANGELES Issue 575 • October 7 - October 13, 2010 OUR 11th Beverly Hills’ Anniversary First Lady The Weekly’s interview with Lonnie Delshad cover story • pages 8-9 Few motorists would risk their lives by for anyone but a Democrat because it would briefs • Lively subway route hearing at briefs • Julian Gold announces rudy cole • Roxbury Park Page 2 candidacy for City Council Page 3 United city speaks Page 6 bicycle community in the region, and isn’t have disappointed his liberal mother. As ALSO ON THE WEB Beverly Hills www.bhweekly.com that part of our transportation problem? Too one of my favorite commentators, Dennis letters too few folks using alternate transportation Prager, pointed out in a recent article, so WeeklySERVING BEVERLY HILLS • BEVERLYWOOD • LOS ANGELES means too many cars on the road. Bike- many registered Democrats vote for Left- Issue 574 • September 30 - October 6, 2010 friendly infrastructure not only protects wing candidates who do not share their Beverly High Athletic cyclists entitled to ride all of the streets in views for purely emotional, nonsensical Alumni to be inducted & email our city, but it reduces motorist liability too. reasons. In Rudy’s case, it is because his Simply put, bikes belong, so let’s plan for mother would disapprove of him voting into Hall of Fame them to accommodate bikes safely. -

Visualizing Levinas:Existence and Existents Through Mulholland Drive

VISUALIZING LEVINAS: EXISTENCE AND EXISTENTS THROUGH MULHOLLAND DRIVE, MEMENTO, AND VANILLA SKY Holly Lynn Baumgartner A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2005 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Kris Blair Don Callen Edward Danziger Graduate Faculty Representative Erin Labbie ii © 2005 Holly Lynn Baumgartner All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor This dissertation engages in an intentional analysis of philosopher Emmanuel Levinas’s book Existence and Existents through the reading of three films: Memento (2001), Vanilla Sky (2001), and Mulholland Drive, (2001). The “modes” and other events of being that Levinas associates with the process of consciousness in Existence and Existents, such as fatigue, light, hypostasis, position, sleep, and time, are examined here. Additionally, the most contested spaces in the films, described as a “Waking Dream,” is set into play with Levinas’s work/ The magnification of certain points of entry into Levinas’s philosophy opened up new pathways for thinking about method itself. Philosophically, this dissertation considers the question of how we become subjects, existents who have taken up Existence, and how that process might be revealed in film/ Additionally, the importance of Existence and Existents both on its own merit and to Levinas’s body of work as a whole, especially to his ethical project is underscored. A second set of entry points are explored in the conclusion of this dissertation, in particular how film functions in relation to philosophy, specifically that of Levinas. What kind of critical stance toward film would be an ethical one? Does the very materiality of film, its fracturing of narrative, time, and space, provide an embodied formulation of some of the basic tenets of Levinas’s thinking? Does it create its own philosophy through its format? And finally, analyzing the results of the project yielded far more complicated and unsettling questions than they answered. -

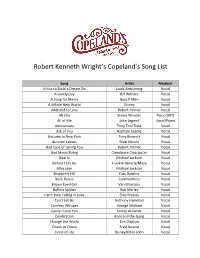

Robert Kenneth Wright's Copeland's Song List

Robert Kenneth Wright’s Copeland’s Song List Song Artist Medium A Kiss to Build a Dream On Louis Armstrong Vocal A Lovely Day Bill Withers Vocal A Song for Mama Boyz II Men Vocal A Whole New World Disney Vocal Addicted to Love Robert Palmer Vocal All I Do Stevie Wonder Piano (WT) All of Me John Legend Vocal/Piano Anniversary Tony Toni Tone Vocal Ask of You Raphael Saadiq Vocal Autumn in New York Tony Bennett Vocal Autumn Leaves Matt Monro Vocal Bad Case of Loving You Robert Palmer Vocal Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Vocal Beat It Michael Jackson Vocal Before I Let Go Frankie Beverly/Maze Vocal Billie Jean Michael Jackson Vocal Blueberry Hill Fats Domino Vocal Brick House Commodores Vocal Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Vocal Buffalo Soldier Bob Marley Vocal Can’t Help Falling in Love Elvis Presley Vocal Can’t Let Go Anthony Hamilton Vocal Careless Whisper George Michael Vocal Cause I Love You Lenny Williams Vocal Celebration Kool and the Gang Vocal Change the World Eric Clapton Vocal Cheek to Cheek Fred Astaire Vocal Circle of Life Disney/Elton John Vocal Close the Door Teddy Pendergrass Vocal Cold Sweat James Brown Vocal Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Vocal Creepin’ Luther Vandross Vocal Dat Dere Tony Bennett Vocal Distant Lover Marvin Gaye Vocal Don’t Stop Believing Journey Vocal Don’t Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Vocal Don’t You Know That Luther Vandross Vocal Early in the Morning Gap Band Vocal End of the Road Boyz II Men Vocal Every Breath You Take The Police Vocal Feelin’ on Ya Booty R. -

Collaborating with James Baldwin on a Screenplay of Giovanni's Room

DISPATCH “We can love one another in other ways”: Collaborating with James Baldwin on a Screenplay of Giovanni’s Room Michael Raeburn Abstract The author discusses his personal relationship with James Baldwin, recounting their collaboration on a film script for an adaptation of Giovanni’s Room. Keywords: Giovanni’s Room, Michael Raeburn, James Baldwin, film, Paris, Marlon Brando, Robert de Niro, Saint-Paul de Vence, Steve McQueen It was a bright summer’s afternoon in the south of France on 2 August 1977. In the garden of his house below the ramparts of the village of Saint-Paul de Vence, James Baldwin was celebrating his 53rd birthday. He made a brief speech thanking his friends for coming. Then, much to my surprise, he announced that he and I had embarked on “an adventure” to write a screenplay of Giovanni’s Room (1956). He raised his glass to me; most of the guests raised theirs to us in hesitant celebration. The idea had occurred a few weeks before. It came from Jimmy; I cannot call him James, as to me, and to all his friends, he was Jimmy. His offer to collaborate on the adaptation had come out of the blue. Only a set of mutually shared circum- stances going back to our first meeting can explain his proposal which was pre- sented to me in these words: “We can also love one another in other ways: we’ll write the script of ‘Giovanni’s Room’ together.” To most outsiders we were the most improbable match: a young, novice film- maker from colonial Africa, and a world-famous African-American writer from Harlem. -

PH - Songs on Streaming Server 1 TITLE NO ARTIST

TITLE NO ARTIST 22 5050 TAYLOR SWIFT 214 4261 RIVER MAYA ( I LOVE YOU) FOR SENTIMENTALS REASONS SAM COOKEÿ (SITTIN’ ON) THE DOCK OF THE BAY OTIS REDDINGÿ (YOU DRIVE ME) CRAZY 4284 BRITNEY SPEARS (YOU’VE GOT) THE MAGIC TOUCH THE PLATTERSÿ 19-2000 GORILLAZ 4 SEASONS OF LONELINESS BOYZ II MEN 9-1-1 EMERGENCY SONG 1 A BIG HUNK O’ LOVE 2 ELVIS PRESLEY A BOY AND A GIRL IN A LITTLE CANOE 3 A CERTAIN SMILE INTROVOYS A LITTLE BIT 4461 M.Y.M.P. A LOVE SONG FOR NO ONE 4262 JOHN MAYER A LOVE TO LAST A LIFETIME 4 JOSE MARI CHAN A MEDIA LUZ 5 A MILLION THANKS TO YOU PILITA CORRALESÿ A MOTHER’S SONG 6 A SHOOTING STAR (YELLOW) F4ÿ A SONG FOR MAMA BOYZ II MEN A SONG FOR MAMA 4861 BOYZ II MEN A SUMMER PLACE 7 LETTERMAN A SUNDAY KIND OF LOVE ETTA JAMESÿ A TEAR FELL VICTOR WOOD A TEAR FELL 4862 VICTOR WOOD A THOUSAND YEARS 4462 CHRISTINA PERRI A TO Z, COME SING WITH ME 8 A WOMAN’S NEED ARIEL RIVERA A-GOONG WENT THE LITTLE GREEN FROG 13 A-TISKET, A-TASKET 53 ACERCATE MAS 9 OSVALDO FARRES ADAPTATION MAE RIVERA ADIOS MARIQUITA LINDA 10 MARCO A. JIMENEZ AFRAID FOR LOVE TO FADE 11 JOSE MARI CHAN AFTERTHOUGHTS ON A TV SHOW 12 JOSE MARI CHAN AH TELL ME WHY 14 P.D. AIN’T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH 4463 DIANA ROSS AIN’T NO SUNSHINE BILL WITHERSÿ AKING MINAHAL ROCKSTAR 2 AKO ANG NAGTANIM FOLK (MABUHAY SINGERS)ÿ AKO AY IKAW RIN NONOY ZU¥IGAÿ AKO AY MAGHIHINTAY CENON LAGMANÿ AKO AY MAYROONG PUSA AWIT PAMBATAÿ PH - Songs on Streaming Server 1 TITLE NO ARTIST AKO NA LANG ANG LALAYO FREDRICK HERRERA AKO SI SUPERMAN 15 REY VALERA AKO’ Y NAPAPA-UUHH GLADY’S & THE BOXERS AKO’Y ISANG PINOY 16 FLORANTE AKO’Y IYUNG-IYO OGIE ALCASIDÿ AKO’Y NANDIYAN PARA SA’YO 17 MICHAEL V. -

General Awareness–Current Affairs Month of March-2019

GENERAL AWARENESS–CURRENT AFFAIRS MONTH OF MARCH-2019 List of Important Days March 1 - Zero Discrimination Day (Theme – “Act to change laws that Discriminate”) March 4 - National Safety Day (Themes – “Cultivate and Sustain A Safety Culture for Building Nation”) Mar 4-10 - National Safety Week March 7 - Janaushadhi Diwas March 8 - International Women’s Day (Theme – “Think Equal, Build Smart, Innovate for Change”). March 12 - World Day against Cyber Censorship March 12 - 30th anniversary of the World Wide Web (WWW) March 14 - (2nd Thursday of March) World Kidney Day (Theme - “Kidney Health for Everyone Everywhere”) March 14 - Pi Day (Pi's value (3.14)) March 15 - World Consumer Rights Day (In India this day is celebrated as Viswa Upabhokta Adhikar Diwas). (Theme – “Trusted Smart Products”) March 20 - International Day of Happiness. (Theme – “Happier Together”) March 20 - World Day of Theatre for Children and Young People March 20 - World Sparrow Day. (Theme – “I LOVE Sparrows”) March 21 - International Day of Forests. (Theme “Forests and Education”) March 21 - World Poetry Day March 21 - World Down Syndrome Day March 21 - International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (Theme – “Mitigating and countering rising nationalist populism and extreme supremacist ideologies”) March 21 - World Puppetry Day March 22 - World Water Day (Theme – “Leaving no one behind”) March 23 - World Meteorological Day (Theme – “The Sun, the Earth and the Weather”) March 23 - 88th Shaheed Diwas (Martyr’s Day) March 24 - World Tuberculosis (TB) Day (Theme – “It’s time”) March 25 - International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and Transatlantic Slave Trade. (Theme – “Remember Slavery: The Power of the Arts for Justice”) March 26 - Independence Day of Bangladesh March 27 - World Theatre Day (WTD) March 30 - Rajasthan Diwas Reserve Bank of India • The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has fined Yes Bank ₹1 crore for not complying with its directions about SWIFT, a financial messaging software. -

Most Requested Songs of 2020

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2020 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

Daryl Lowery Sample Songlist Bridal Songs

DARYL LOWERY SAMPLE SONGLIST BRIDAL SONGS Song Title Artist/Group Always And Forever Heatwave All My Life K-Ci & Jo JO Amazed Lonestar At Last Etta James Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Breathe Faith Hill Can't Help Falling In Love Elvis Presley Come Away With Me Nora Jones Could I Have This Dance Anne Murray Endless Love Lionel Ritchie & Diana Ross (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams From This Moment On Shania Twain & Brian White Have I Told You Lately Rod Stewart Here And Now Luther Van Dross Here, There And Everywhere Beatles I Could Not Ask For More Edwin McCain I Cross My Heart George Strait I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees I Don't Want To Miss A Thing Aerosmith I Knew I Loved You Savage Garden I'll Always Love You Taylor Dane In Your Eyes Peter Gabriel Just The Way You Are Billy Joel Keeper Of The Stars Tracy Byrd Making Memories Of Us Keith Urban More Than Words Extreme One Wish Ray J Open Arms Journey Ribbon In The Sky Stevie Wonder Someone Like You Van Morrison Thank You Dido That's Amore Dean Martin The Way You Look Tonight Frank Sinatra The Wind Beneath My Wings Bette Midler Unchained Melody Righteous Brothers What A Wonderful World Louis Armstrong When A Man Loves A Woman Percy Sledge Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton You And Me Lifehouse You're The Inspiration Chicago Your Song Elton John MOTHER/SON DANCE Song Title Artist/Group A Song For Mama Boyz II Men A Song For My Son Mikki Viereck You Raise Me Up Josh Groban Wind Beneath My Wings Bette Midler FATHER/DAUGHTER DANCE Song Title Artist/Group Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Butterfly Kisses Bob Carlisle Daddy's Little Girl Mills Brothers Unforgettable Nat & Natalie King Cole What A Wonderful World Louis Armstrong Popular Selections: "Big Band” To "Hip Hop" Song Title Artist/Group (Oh What A Night) December 1963 Four Seasons 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 21 Questions 50 Cent 867-5309 Tommy Tutone A New Day Has Come Celine Dion A Song For My Son Mikki Viereck A Thousand Years Christine Perri A Wink And A Smile Harry Connick, Jr. -

English Songs

English Songs 18000 04 55-Vũ Luân-Thoại My 18001 1 2 3-Gloria Estefan 18002 1 Sweet Day-Mariah Carey Boyz Ii M 18003 10,000 Promises-Backstreet Boys 18004 1999-Prince 18005 1everytime I Close My Eyes-Backstr 18006 2 Become 1-Spice Girls 18007 2 Become 1-Unknown 18008 2 Unlimited-No Limit 18009 25 Minutes-Michael Learns To Rock 18010 25 Minutes-Unknown 18011 4 gio 55-Wynners 18012 4 Seasons Of Lonelyness-Boyz Ii Me 18013 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover-Paul S 18014 500 Miles Away From Home-Peter Pau 18015 500 Miles-Man 18016 500 Miles-Peter Paul-Mary 18017 500 Miles-Unknown 18018 59th Street Bridge Song-Classic 18019 6 8 12-Brian McKnight 18020 7 Seconds-Unknown 18021 7-Prince 18022 9999999 Tears-Unknown 18023 A Better Love Next Time-Cruise-Pa 18024 A Certain Smile-Unknown 18025 A Christmas Carol-Jose Mari Chan 18026 A Christmas Greeting-Jeremiah 18027 A Day In The Life-Beatles-The 18028 A dear John Letter Lounge-Cardwell 18029 A dear John Letter-Jean Sheard Fer 18030 A dear John Letter-Skeeter Davis 18031 A dear Johns Letter-Foxtrot 18032 A Different Beat-Boyzone 18033 A Different Beat-Unknown 18034 A Different Corner-Barbra Streisan 18035 A Different Corner-George Michael 18036 A Foggy Day-Unknown 18037 A Girll Like You-Unknown 18038 A Groovy Kind Of Love-Phil Collins 18039 A Guy Is A Guy-Unknown 18040 A Hard Day S Night-The Beatle 18041 A Hard Days Night-The Beatles 18042 A Horse With No Name-America 18043 À La Même Heure Dans deux Ans-Fema 18044 A Lesson Of Love-Unknown 18045 A Little Bit Of Love Goes A Long W- 18046 A Little Bit-Jessica