Introduction to the Landscapes and Soils of the Hamilton Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Links October 2011

Project update Issue 02 Southern Links October 2011 Preferred Network Open Days Since the community information days in April this year, On 1 December, at the Tamahere venue, the Southern Links project team has been busy analysing there will also be information available feedback from the more than 600 people who attended. on the Tamahere section of the Waikato Further technical studies have also been undertaken. Expressway project, south of the SH1 interchange. A multi-criteria analysis process is now Southern Links Information Days On 27 October at the Tamahere being used to evaluate options and Tuesday, 29 November, 2 - 7pm Community Hall, a separate open day is refine the project focus. Along with Glenview Club, 211 Peacockes Road, being held jointly by the NZ Transport the concerns of property owners and Hamilton Agency and Waikato District Council for local residents, the project team is also the Hamilton Southern Interchange (part Thursday 1 December, 2 - 7pm working with other stakeholders and of the Hamilton section of the Waikato Tamahere Community Centre, Devine tangata whenua to understand their Expressway), and the council’s Tamahere Road, Tamahere views. Structure Plan. Saturday 3 December, 10am - 2pm, Our next information days for Southern Southern Links information will focus Rukuhia Community Hall, Rukuhia Links are planned in the Glenview, on the selection of a preferred network Road, Rukuhia Rukuhia and Tamahere areas for late corridor while the Waikato Expressway November and early December. Their not conflict with information days for project, which is further advanced, will timing has been been put back so as to other related projects. -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No. 121

3494 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No. 121 Classif!calion of Roads in Matamala County. Jones Road, Putarnru. Kerr's Road, Te Poi. Kopokorahi or Wawa Ron.ct. N p11rsuance and exercise of t~.e powers conferred on him Kokako Road, Lichfield. I by the Transport Department Act, 1929, and the Heavy Lake Road, Okoroire. Lichfield--Waotu Road. :VIotor-vchiclc Regulations 1940; the Minister of Tmnsport Leslie's Road Putaruru. Livingst,one's Road, Te Po.i. does here by revoke the Warrant classifying roads in the Lei.vis Road, Okoroire. Luck-at-Last Road, :.I\Taunga.- lVlatamata County dated the 11th day of October, 1940, and Lichfield-Ngatira Road. tautari. published in the New Zealand Gazette No. 109 of the 31st lvfain's Road, Okoroire. Matamata-vVaharoa Ro a. d day of October, 1940, at ps,ge 2782, and does hereby declare lWaiRey's Road, \Vaharoa. (East). that the roads described in the Schedule hereto and situated Mangawhero or Taihoa. Road. Iviata.nuku Road, Tokoroa. in the Matamata County shall belong to tho respective J\faraetai Road, Tokoroa. 1\faungatautari ]/fain ltmuJ. classes of roads shown in the said Schedule. J\fatai Road. MeM:illan's Road, Okoroire. lvlatamata-Hinnera. Road l\foNab's Road, 'l'e Poi. (West). Moore's Road, Hinuera. SCHEDULE. :Th!Ia,tamata-Turanga.-o-moana l\'Iorgan1s Road, Peria. MATAMATA COUNTY. - Gordon Road (including l\'Iuirhead's Road, Whitehall. Tower Road). l\1urphy Road, Tirau. RoAbs classified in Class Three : Available for tho use thereon of any multi-axled heavy motor-vehicle or any Nathan's Road, Pnket,urna. -

Waikato Sports Facility Plan Reference Document 2 June 2014

Waikato Sports Facility Plan Reference Document JUNE 2014 INTERNAL DRAFT Information Document Reference Waikato Sports Facility Plan Authors Craig Jones, Gordon Cessford Sign off Version Internal Draft 4 Date 4th June 2014 Disclaimer: Information, data and general assumptions used in the compilation of this report have been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. Visitor Solutions Ltd has used this information in good faith and makes no warranties or representations, express or implied, concerning the accuracy or completeness of this information. Interested parties should perform their own investigations, analysis and projections on all issues prior to acting in any way with regard to this project. Waikato Sports Facility Plan Reference Document 2 June 2014 Waikato Sports Facility Plan Reference Document 3 June 2014 CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 5 2.0 Our challenges 8 3.0 Our Choices for Maintaining the network 9 4.0 Key Principles 10 5.0 Decision Criteria, Facility Evaluation & Funding 12 6.0 Indoor Court Facilities 16 7.0 Aquatic Facilities 28 8.0 Hockey – Artifical Turfs 38 9.0 Tennis Court Facilities 44 10.0 Netball – Outdoor Courts 55 11.0 Playing Fields 64 12.0 Athletics Tracks 83 13.0 Equestrian Facilities 90 14.0 Bike Facilities 97 15.0 Squash Court Facilities 104 16.0 Gymsport facilities 113 17.0 Rowing Facilities 120 18.0 Club Room Facilities 127 19.0 Bowling Green Facilities 145 20.0 Golf Club Facilities 155 21.0 Recommendations & Priority Actions 165 Appendix 1 - School Facility Survey 166 Waikato Sports Facility Plan Reference Document 4 June 2014 1.0 INTRODUCTION Plan Purpose The purpose of the Waikato Facility Plan is to provide a high level strategic framework for regional sports facilities planning. -

Attachment 4

PARK ROAD SULLIVAN ROAD DIVERS ROAD SH 1 LAW CRESCENT BIRDWOOD ROAD WASHER ROAD HOROTIU BRIDGE ROAD CLOVERFIELD LANE HOROTIU ROAD KERNOTT ROAD PATERSON ROAD GATEWAY DRIVE EVOLUTION DRIVE HE REFORD D RIVE IN NOVA TIO N W A Y MARTIN LANE BOYD ROAD HENDERSON ROAD HURRELL ROAD HUTCHINSON ROAD BERN ROAD BALLARD ROAD T NNA COU R VA SA OSBORNE ROAD RK D RIVER DOWNS PA RIVE E WILLIAMSON ROAD G D RI ONION ROAD C OU N T REYNOLDS ROAD RY L ANE T E LANDON LANE R A P A A ROAD CESS MEADOW VIEW LANE Attachment 4 C SHERWOOD DOWNS DRIVE HANCOCK ROAD KAY ROAD REDOAKS CLOSE REID ROAD RE E C SC E V E EN RI L T IV D A R GRANTHAM LANE KE D D RIVERLINKS LANE RIVERLINKS S K U I P C A E L O M C R G N E A A A H H D O LOFTUS PLACE W NORTH CITY ROAD F I ONION ROAD E LD DROWERGLEN S Pukete Farm Park T R R O SE EE T BE MCKEE STREET R RY KUPE PLACE C LIMBER HILL HIGHVIEW COURT RESCENT KESTON CRESCENT VIKING LANE CLEWER LANE NICKS WAY CUM BE TRAUZER PLACE GRAHAM ROAD OLD RUFFELL ROAD RLA KOURA DRIVE ND DELIA COURT DR IV ET ARIE LANE ARIE E E SYLVESTER ROAD TR BREE PLACE E S V TRENT LANE M RI H A D ES G H UR C B WESSEX PLACE WALTHAM PLACE S GO R IA P Pukete Farm Park T L T W E M A U N CE T I HECTOR DRIVE I A R H E R S P S M A AMARIL LANE IT IR A N M A N I N G E F U A E G ED BELLONA PLACE Y AR D M E P R S T L I O L IN Moonlight Reserve MAUI STREET A I A L G C A P S D C G A D R T E RUFFELL ROAD R L L A O E O N R A E AVALON DRIVEAVALON IS C N S R A E R E D C Y E E IS E E L C N ANN MICHELE STREET R E A NT ESCE NT T WAKEFIELD PLACE E T ET B T V TE KOWHAI ROAD KAPUNI STRE -

Ages on Weathered Plio-Pleistocene Tephra Sequences, Western North Island, New Zealand

riwtioll: Lowe. D. ~.; TiP.I>CU. J. M.: Kamp. P. J. J.; Liddell, I. J.; Briggs, R. M.: Horrocks, 1. L. 2001. Ages 011 weathered Pho-~Je.stocene tephra sequences, western North Island. New Zealand. Ill: Juviglle. E.T.: Raina!. J·P. (Eds). '"Tephras: Chronology, Archaeology', CDERAD editeur, GoudeL us Dossiers de f'ArcMo-Logis I: 45-60. Ages on weathered Plio-Pleistocene tephra sequences, western North Island, New Zealand Ages de sequences de tephras Plio-Pleistocenes alteres, fie du Nord-Ouest, Nouvelle lelande David J. Lowe·, J, Mark Tippett!, Peter J. J, Kamp·, Ivan J. LiddeD·, Roger M. Briggs· & Joanna L. Horrocks· Abstract: using the zircon fISsion-track method, we have obtainedfive ages 011 members oftwo strongly-...-eathered. silicic, Pliocene·Pleislocelle tephra seql/ences, Ihe KOIIIUQ and Hamilton Ashformalions, in weslern North !sland, New Zealand. These are Ihe jirst numerical ages 10 be oblained directly on these deposils. Ofthe Kauroa Ash sequence, member KI (basal unit) was dated at 2,24 ± 0.19 Ma, confirming a previous age ofc. 1.25 Ma obtained (via tephrochronology)from KlAr ages on associatedbasalt lava. Members K1 and X3 gave indistinguishable ages between 1,68.±0,/1 and 1.43 ± 0./7 Ma. Member K11, a correlQlilV! ojOparau Tephra andprobably also Ongatiti Ignimbrite. was dated at 1.18:i: 0.11 Ma, consistent with an age of 1.23 ± 0.02 Ma obtained by various methodr on Ongaiiti Ignimbrite. Palaeomagnetic measurements indicated that members XI3 to XIJ (top unit, Waiterimu Ash) are aged between c. 1.2 Ma and O. 78 Mo. Possible sources of/he Kauroa Ash Formation include younger \!Oleanic centres in the sOllthern Coromandel Volcanic Zone orolder volcanic cenlres in the Taupo Volcanic Zone, or both. -

Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand

A supplementary finding-aid to the archives relating to Maori Schools held in the Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand MAORI SCHOOL RECORDS, 1879-1969 Archives New Zealand Auckland holds records relating to approximately 449 Maori Schools, which were transferred by the Department of Education. These schools cover the whole of New Zealand. In 1969 the Maori Schools were integrated into the State System. Since then some of the former Maori schools have transferred their records to Archives New Zealand Auckland. Building and Site Files (series 1001) For most schools we hold a Building and Site file. These usually give information on: • the acquisition of land, specifications for the school or teacher’s residence, sometimes a plan. • letters and petitions to the Education Department requesting a school, providing lists of families’ names and ages of children in the local community who would attend a school. (Sometimes the school was never built, or it was some years before the Department agreed to the establishment of a school in the area). The files may also contain other information such as: • initial Inspector’s reports on the pupils and the teacher, and standard of buildings and grounds; • correspondence from the teachers, Education Department and members of the school committee or community; • pre-1920 lists of students’ names may be included. There are no Building and Site files for Church/private Maori schools as those organisations usually erected, paid for and maintained the buildings themselves. Admission Registers (series 1004) provide details such as: - Name of pupil - Date enrolled - Date of birth - Name of parent or guardian - Address - Previous school attended - Years/classes attended - Last date of attendance - Next school or destination Attendance Returns (series 1001 and 1006) provide: - Name of pupil - Age in years and months - Sometimes number of days attended at time of Return Log Books (series 1003) Written by the Head Teacher/Sole Teacher this daily diary includes important events and various activities held at the school. -

Proposed Waikato District Plan, Hearing 25: Zone Extents, Mercer and Meremere Highlights Statement from Paula Rolfe Hd Land

PROPOSED WAIKATO DISTRICT PLAN, HEARING 25: ZONE EXTENTS, MERCER AND MEREMERE HIGHLIGHTS STATEMENT FROM PAULA ROLFE HD LAND LIMITED AND HAMPTON DOWNS (NZ) LIMITED FURTHER SUBMISSION 1194 TO REID INVESTMENT TRUST (SUBMISSION 718) 1. HD Land Ltd and Hampton Downs (NZ) Ltd (“HD Land”) seek to retain the zoning of the Hampton Downs Motor Sport and Recreation Zone (HDMSR) as proposed. 2. HD Land opposes the submission by submitter number 783 Reid Investment Trust (RIT) which seeks to rezone the site as identified below from rural to the HDMSR zone and to include the site within Precinct E, as weLL as to change the zoning provisions to cater for future industriaL deveLopment on lot 6 DP 411257. Subject site – Lot 6 DP 411257, 17 ha for industrial 1.3587 ha available in Precinct B 3. Evidence on behaLf of RIT prepared by ALastair Wyatt dated 12 February 2021 has undertaken a s32 analysis of the site identifying two rezoning avenues of the site. These include: a) Rezone the site from rural to “industriaL” b) Rezone the site from ruraL to HDMSR zone with a new Precinct F enabling both industrial activities and event carparking or include the site within the eXisting Precinct B. GeneraLLy speaking HD Land do not oppose the deveLopment by RIT but any development must be undertaken with sufficient detaiL to ensure that alL reverse sensitivity risk is resolved. As background to these concerns HighLand’s Motorsport Park (Hampton Down’s sister track) has been engaged in on-going regulatory proceedings in order to protect themselves from reverse sensitivity effects. -

Matamata-Piako District Detailed Population and Dwelling Projections to 2045

Matamata-Piako District Detailed Population and Dwelling Projections to 2045 February 2015 Report prepared by: for: Matamata-Piako District Detailed Population and Dwelling Projections to 2045 Quality Assurance Statement Rationale Limited Project Director: Tom Lucas 5 Arrow Lane Project Manager: Walter Clarke PO Box 226 Arrowtown 9302 Prepared by: Walter Clarke New Zealand Approved for issue by: Tom Lucas Phone/Fax: +64 3 442 1156 Document Control G: \1 - Local Government\Thames_Coromandel\01 - Growth Study\2013\MPDC\Urban Analysis\MPDC Detailed Growth Projections to 2045_Final.docx Version Date Revision Details Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by 1 23/12/14 Draft for Client JS WC WC 2 03/02/15 Final WC WC WC MATAMATA-PIAKO DISTRICT COUNCIL STATUS: FINAL 03 FEBRUARY 2015 REV 2 PAGE 2 Matamata-Piako District Detailed Population and Dwelling Projections to 2045 Table of Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Population ................................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Dwellings .................................................................................................................................... 6 3 Results ............................................................................................................................................... -

Te Awamutu Courier Thursday, October 15, 2020 Firefighter’S 50 Years Marked

Te Awamutu Next to Te Awamutu The Hire Centre Te Awamutu Landscape Lane, Te Awamutu YourC community newspaper for over 100 years Thursday, October 15, 2020 0800 TA Hire | www.hirecentreta.co.nz BRIEFLY Our face on show The Our Face of 2020 Art Exhibition is being held at the Te Awamutu i-Site Centre Burchell Pavilion this weekend. The exhibition features works from local Rosebank artists and is open daily from 10am- 4pm, Friday — Sunday, October 16 — 18. Pirongia medical clinic resumes Mahoe Medical Centre’s weekly satellite clinic at Pirongia with Dr Fraser Hodgson will re-commence this month from Thursday, October 29. Clinics are at St Saviour's Church, phone 872 0923 for an appointment. In family footsteps Robyn and Dean Taylor live and work locally, but they have wide horizons which they fully explore. Hear them talk about a recent visit to South Africa at the Continuing Education Group’s meeting on Wednesday, Rob Peters presents Murry Gillard with a life member’s gift. Photos / Supplied October 21 in the Waipa¯ Workingmen’s Club. See details in classified section or phone 871 6434 or 870 3223. Housie fundraiser Rosetown Lions Club is 50 years of service holding a fundraising afternoon this Saturday with proceeds supporting youth in our community. Te Awamutu firefighter Murry Gillard made a life member after first joining in 1970 The Housie Afternoon takes place at Te Awamutu RSA fter Covid-19 forced the brigade’s 1934 Fordson V8 appliance The official party was made up of averaged 97 per cent in the 50 years. -

The Characteristics and Impacts of Landfill Leachate from Horotiu

http://waikato.researchgateway.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. The characteristics and impacts of landfill leachate from Horotiu, New Zealand and Maseru, Lesotho: A comparative study A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Environmental Science at The University of Waikato by Thabiso Mohobane 2008 Abstract Landfills are a potential pollution threat to both ground and surface water resources. This study focuses on two landfills, the Horotiu municipal waste landfill, near Hamilton, New Zealand, and the Maseru landfill in Lesotho. The Horotiu landfill is located less than 50 metres from the Waikato River and also sits on a shallow (< lm to water table) aquifer. In Lesotho, the Maseru landfill is 4 km from a river and 2 km from a water reservoir and rests on a huge aquifer. Over 5000 people depend on groundwater in the area between the landfill and the river. -

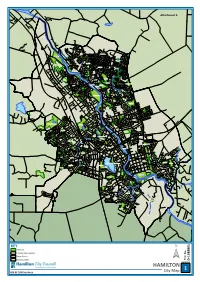

List of Road Names in Hamilton

Michelle van Straalen From: official information Sent: Monday, 3 August 2020 16:30 To: Cc: official information Subject: LGOIMA 20177 - List of road and street names in Hamilton. Attachments: FW: LGOIMA 20177 - List of road and street names in Hamilton. ; LGOIMA - 20177 Street Names.xlsx Kia ora Further to your information request of 6 July 2020 in respect of a list of road and street names in Hamilton, I am now able to provide Hamilton City Council’s response. You requested: Does the Council have a complete list of road and street names? Our response: Please efind th information you requested attached. We trust this information is of assistance to you. Please do not hesitate to contact me if you have any further queries. Kind regards, Michelle van Straalen Official Information Advisor | Legal Services | Governance Unit DDI: 07 974 0589 | [email protected] Hamilton City Council | Private Bag 3010 | Hamilton 3240 | www.hamilton.govt.nz Like us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter This email and any attachments are strictly confidential and may contain privileged information. If you are not the intended recipient please delete the message and notify the sender. You should not read, copy, use, change, alter, disclose or deal in any manner whatsoever with this email or its attachments without written authorisation from the originating sender. Hamilton City Council does not accept any liability whatsoever in connection with this email and any attachments including in connection with computer viruses, data corruption, delay, interruption, unauthorised access or unauthorised amendment. Unless expressly stated to the contrary the content of this email, or any attachment, shall not be considered as creating any binding legal obligation upon Hamilton City Council. -

Cultural Impact Assessment Report Te Awa Lakes Development

Cultural Impact Assessment Report Te Awa Lakes Development 9 October 2017 Document Quality Assurance Bibliographic reference for citation: Boffa Miskell Limited 2017. Cultural Impact Assessment Report: Te Awa Lakes Development. Report prepared by Boffa Miskell Limited for Perry Group Limited. Prepared by: Norm Hill Kaiarataki - Te Hihiri / Strategic Advisor Boffa Miskell Limited Status: [Status] Revision / version: [1] Issue date: 9 October 2017 Use and Reliance This report has been prepared by Boffa Miskell Limited on the specific instructions of our Client. It is solely for our Client’s use for the purpose for which it is intended in accordance with the agreed scope of work. Boffa Miskell does not accept any liability or responsibility in relation to the use of this report contrary to the above, or to any person other than the Client. Any use or reliance by a third party is at that party's own risk. Where information has been supplied by the Client or obtained from other external sources, it has been assumed that it is accurate, without independent verification, unless otherwise indicated. No liability or responsibility is accepted by Boffa Miskell Limited for any errors or omissions to the extent that they arise from inaccurate information provided by the Client or any external source. Template revision: 20171010 0000 File ref: H17023_Te_Awa_Lakes_Cultural_Impact_.docx Protection of Sensitive Information The Tangata Whenua Working Group acknowledges and supports s42 of the Resource Management Act 1991, which effectively protects intellectual property and sensitive information. As a result, the Tangata Whenua Working Group may request that evidence provided at a subsequent hearing be held in confidence by the Council.