Richard Foster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Hook L’Haçienda La Meilleure Façon De Couler Un Club

PETER HOOK L’HAÇIENDA LA MEILLEURE FAÇON DE COULER UN CLUB LE MOT ET LE RESTE PETER HOOK L’HAÇIENDA la meilleure façon de couler un club traduction de jean-françois caro le mot et le reste 2020 Ce livre est dédié à ma mère, Irene Hook, avec tout mon amour Reposez en paix : Ian Curtis, Martin Hannett, Rob Gretton, Tony Wilson et Ruth Polsky, sans qui l’Haçienda n’aurait jamais été construite LES COUPABLES Bien sûr que ça me poserait problème. Lorsque Claude Flowers m’a suggéré en 2003 d’écrire mes mémoires sur l’Haçienda, la première chose qui me vint à l’esprit est cette célèbre citation au sujet des années soixante : si vous vous en souvenez, c’est que vous n’y étiez pas. Tel était mon sentiment au sujet de l’Haç. J’allais donc avoir besoin d’un peu d’aide, et ce livre est le fruit d’un effort collectif. Claude a lancé les hostilités et m’a invité à me replonger dans de très nombreux souvenirs que je pensais avoir oubliés, tandis qu’Andrew Holmes m’a fourni ces « interludes » essentielles tout en se chargeant des démarches administratives. Je m’attribue le mérite de tout ce qui vous plaira dans ce livre. Si des passages vous déplaisent, c’est à eux qu’il faudra en vouloir. Avant-propos Nous avons vraiment fait n’importe quoi. Vraiment ? À y repenser aujourd’hui, je me le demande. Nous sommes en 2009 et l’Haçienda n’a jamais été aussi célèbre. En revanche, elle ne rapporte toujours pas d’argent ; rien n’a changé de ce côté-là. -

Recycle This, BITCH" March 10, 1999

Vol. XX No.11 "Recycle this, BITCH" March 10, 1999 i~Ci MA 4X T w:^.. IA ··-··--~pe ISSUES -------- monsoons_- ~ararwaa~R -rra~*r~ua~%pla -r ~-~------~-4C ~- C-RC~· IB-WHO'S --~--- ~~P - ---- -- -~rm~la~lsl·I~B~B~·lP~ GOTL- C~L~P~s~s~6~~ OURbd - pC_~P- ~-~-····IP·-CPIB-D------~lr-BACK? -~-L~B ~9 1 ~L_~Llb-~·~IP~ ~------ 1~-9- CI·lll eC __LP~·C~IB1-I By Terry McLaren will make it impossible for many to stay in school at we were able to have a productive conversation. all. Remember: If you go part time, no TAP for you! Englebright denounced the proposed cuts "It should be a no-brainer to make college Then there's the incentive to graduate in to SUNY as "pure meanness" and asserted that they accessible to all," said Blair Horner, legislative coor- four years. Yes, it is possible, but not for everyone. It were an assault on the state's brightest promise- dinator for NYPIRG. He addressed an enthusiastic also is not the best choice for some. In order to SUNY. We even got down to chatting about the group of almost 400 students on their way to increase their employment potential, more and more trustees' proposed core curriculum changes. appointments with senators and assembly people. students are choosing double majors. This increases Englebright, a PhD in Geology and USB lecturer, Welcome to Higher Ed Lobby Day. the number of courses they have to take, and there- stated that it's "absurd for politicians' decision mak- When fighting against proposed cuts to fore their time of study. -

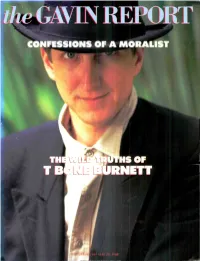

Confessions of a Moralist Hs Of

CONFESSIONS OF A MORALIST HS OF RNETT ISSU www.americanradiohistory.com THE NEW SINGLE PRODUCED BY RON NEVISON FROM THE FORTHCOMING ALBUM 19 Direction: Howard Kaufman/Front Line Management 41) 1988 Reprise Records 'CHICAGO" and esgo " are marks owned by CHICAGO MUSIC, INC.These marks are register-_d in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, and in foreign countrie , and licensed for use to REPRISE RECORDS. www.americanradiohistory.com the GAVIN REPORT TOP 40 MOST ADDED 2W LW TW BILLY OCEAN (102) (Jive /Arista) 4 1 1 GEORGE MICHAEL - One More Try (Columbia) TERENCE TRENT D'ARBY (100) (Columbia) 2 2 2 Johnny Hates Jazz - Shattered Dreams (Virgin) RICHARD MARX (92) 8 6 3 DARYL HALL & JOHN OATES - Everything Your Heart Desires (Arista) (EMI - Manhattan) ERIC CARMEN (89) 5 5 4 Pet Shop Boys - Always On My Mind (EMI- Manhattan) (Arista) RICK ASTLEY - Together Forever (RCA) HENRY LEE SUMMER (55) 11 7 5 (CBS Assoc.) 3 4 6 Foreigner - I Don't Want To Live Without You (Atlantic) AL B. SURE! (54) (Warner Bros.) 1 3 7 Gloria Estefan & MSM - Anything For You (Epic) SADE (52) 8 DEBBIE GIBSON - Foolish Beat (Atlantic) (Epic) 20 12 PEBBLES (51) 13 10 9 The Deele - Two Occasions (Solar /Capitol) (MCA) 19 11 10 BELINDA CARLISLE - Circle In The Sand (MCA) CERTIFIED 10 9 11 Samantha Fox - Naughty Girls (Need Love Too) (Jive /Arista) INXS 24 16 12 CHEAP TRICK - The Flame (Epic) New Sensation 17 14 13 TIMES TWO - Strange But True (Reprise) (Atlantic) 18 15 14 CHER - We All Sleep Alone (Geffen) - Dirty Diana (Epic) PEBBLES 30 19 15 MICHAEL JACKSON Mercedes Boy 28 17 16 BRUCE HORNSBY & THE RANGE - The Valley Road (RCA) (MCA) 26 18 17 THE JETS - Make It Real (MCA) 7 8 18 White Lion - Wait (Atlantic) RECORD 29 23 19 LITA FORD - Kiss Me Deadly (Dreamland /RCA) TO WATCH 33 24 20 PRINCE - Alphabet St. -

The Tiger Time Out! Vol. 1 Issue 1 1994-01-20

Clemson's Guide to Entertainment & the Arts Volume I, No. 1 Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina January 20, 1994 Brooks Center Open! tME- OUT The Gathering Phridaz page 5 Erik Martin /interim head photographer Cayce Crenshaw practices her flute playing in one of the Brook's Center practice rooms Performing arts dances into future , ^ , _P„JL... ^ <-™L- ^HHPH that a np.rfnrminj? arts Dr. Mark Hosier. "A good facility proves by Caroline■ Godbey Cook added that a performing arts the value of the performing arts, and the staff writer building has been envisioned for quite a long time, and recently the need was ad- arts are important to students no matter After six years of planning, numerous dressed by President Max Lennon. what your major is." The outside may not be so pleasing to The 2 Tone delays, and lots of talk, the Brooks Center Six years ago he met with campus the eye since the landscaping is not com- for the Performing Arts is finally open. planners and an outside consultant to plete, but the inside is a totally different Collection Located behind the Strom Thurmond In- project the program's needs. Approxi- story. "It's really nice once you're inside stitute and next to Lehotsky Hall, the mately 150 possible designs were submit- and have gotten around the mud," said Brooks Center will serve students who are ted from architectural firms all over the Birma Gainor, who is involved in chorus involved in music, drama and dance. As country, Cook said. The firm who submit- and has a music theory class in the Brooks The Melvins new home of these students, it will put ted the chosen design was Sert, Jackson them all together for the first time, bring- and Associates of Cambridge, Center. -

NR 04/3 Citroengeel-Mira Calex

v.u. Jo Lijnen, Burg. Bollenstr. 54-56+, 3500 Hasselt BELGIE-BELGIQUE P. B. 3500 Hasselt 1 12/741 E E 3500-HASSELT BURG.BOLLENSTR.54-56+ KUNSTENCENTRUM 3500-HASSELT BURG.BOLLENSTR.54-56+ KUNSTENCENTRUM B B L L WARP NIGHT-MIRACALIX (UK)-29mei‘04 WARP NIGHT-MIRACALIX (UK)-29mei‘04 WARP NIGHT-MIRACALIX (UK)-29mei‘04 WARP NIGHT-MIRACALIX (UK)-29mei‘04 WARP NIGHT-MIRACALIX (UK)-29mei‘04 G G I I E E ”NEW-RELEASES” / 14°jaargang / 5 X per jaar:jan.-mrt-mei-juli-okt/ editie:mei. 2004 Afgiftekantoor: 3500 Hasselt 1 - P 206555 ✯ ININ THETHE CUTCUT (AUS/USA/UK / 2003 / 120’ / 35 mm) Cast Meg Ryan, Mark Ruffalo, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Nick Damici, Regie: Jane Campion Sharrieff Pugh, Michael Nuccio, Alison Nega, Dominick Aries, Susan Gardner, Heather Litteer, Daniel T. Booth, Kevin Bacon Muziek Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson (zie Sigur Ros, Psychic TV, Current 93) Frannie (Meg Ryan) is een in zichzelf gekeerde, alleenstaande Engelse literatuur- docente die les geeft aan een middelbare school in Manhattens East Village. Behalve haar studie over het gebruik van slangwoorden bij jongeren en haar passie voor politieromans houdt ze zich ver van de donkere kant van het grootstadsleven. Tijdens een bezoek aan een bar is ze ongewild getuige van een intiem moment tussen een man en een vrouw. Verschrikt, maar evenzeer gefascineerd door de passie tussen deze twee vreemden, merkt ze slechts de zwoele blik en een tatoeage op van de man. Als er daags nadien een moord blijkt te zijn gepleegd in de buurt van Franny’s huis, wordt ze benaderd door detective Malloy (Mark Ruffalo), die vermoedt dat Franny meer weet. -

Music & Entertainment

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester Director Shuttleworth Director Director Music & Entertainment Tuesday 18th & Wednesday 19th May 2021 at 10:00 Viewing by strict appointment from 6th May For enquires relating to the Special Auction Services auction, please contact: Plenty Close Off Hambridge Road NEWBURY RG14 5RL Telephone: 01635 580595 Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com David Martin Dave Howe Music & Music & Entertainment Entertainment Due to the nature of the items in this auction, buyers must satisfy themselves concerning their authenticity prior to bidding and returns will not be accepted, subject to our Terms and Conditions. Additional images are available on request. Buyers Premium with SAS & SAS LIVE: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price the-saleroom.com Premium: 25% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 30% of the Hammer Price 10. Iron Maiden Box Set, The First Start of Day One Ten Years Box Set - twenty 12” singles in ten Double Packs released 1990 on EMI (no cat number) - Box was only available The Iron Maiden sections in this auction by mail order with tokens collected from comprise the first part of Peter Boden’s buying the records - some wear to edges Iron Maiden collection (the second part and corners of the Box, Sleeves and vinyl will be auctioned in July) mainly Excellent to EX+ Peter was an Iron Maiden Superfan and £100-150 avid memorabilia collector and the items 4. Iron Maiden LP, The X Factor coming up in this and the July auction 11. Iron Maiden Picture Disc, were his pride and joy, carefully collected Double Album - UK Clear Vinyl release 1995 on EMI (EMD 1087) - Gatefold Sleeve Seventh Son of a Seventh Son - UK Picture over 30 years. -

Description Basic Data

[ Weitere Angaben: https://berlin.museum-digital.de/index.php?t=objekt&oges=91270 vom 25.09.2021 ] Objekt: Minimal Compact 15.9.1987 I Museum: SchwulesMuseum L¨utzowstraße 73 10785 Berlin 030 69 59 92 52 [email protected] Rita Maier / Schwules Museum Berlin [RR-P] Sammlung: Nachlass Petra Gall, Fotosammlung Inventarnummer: F-NL-PGA-1-475 Beschreibung Kontaktabzug von 24 Schwarzweißnegativen, die Petra Gall am 15. September 1987 bei einem Konzert der israelischen Post-Punk-Band Minimal Compact aufgenommen hat. Das Konzert fand im Loft am Nollendorfplatz in Berlin statt. Minimal Comapct bestanden aus Malka Spigel (Bass, Gesang), Samy Birnbach (Gesang + Texte), Berry Sakharof (Guitars, Keyboards, Gesang), Max Franken (Schlagzeug) und Rami Fortis (Gitarre, Gesang). Der Schlagzeuger, vermutlich Franken, ist auf den Fotos nicht zu sehen. Die Band existierte von 1981 bis 1988 und arbeitete u.a. mit Tuxedomoon und Wire zusammen. 1987 steuerten Minimal Compact den Song ”When I’m Gone” zu Wim Wenders Film ”Der Himmel ¨uber Berlin” (”Wings of Desire”) bei. Sakharof wurde sp¨ater einer der erfolgreichsten israelischen Rockstars. Die ersten vier Bilder zeigen vermutlich die Band Set Fatale, die als Vorband spielte. Grunddaten Maße 18,3x23,8cm Material/Technik Silbergelatine-Print, KODAK TMX 5052 Ereignisse Wurde abgebildet (Akteur) ... Minimal Compact Wurde abgebildet (Akteur) ... Malka Spigel (1954-) Wurde abgebildet (Akteur) ... Samy Birnbach (1948-) Wurde abgebildet (Akteur) ... Berry Sakharof (1957-) Wurde abgebildet (Akteur) ... Rami Fortis (1954-) Wurde abgebildet (Akteur) ... Max Franken Wurde abgebildet (Akteur) ... Set Fatale Wurde abgebildet (Akteur) ... Cem Oral Wurde abgebildet (Akteur) ... Robert Cobernus Aufgenommen ... wann 15.09.1987 wer Petra Gall (1955-2018) wo Loft (Berlin, Nollendorfplatz) Schlagworte ❼ Ereignis ❼ Fotografie (Methode) ❼ Konzert ❼ Post Punk. -

Various It's a Crammed, Crammed World! 2 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various It's A Crammed, Crammed World! 2 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: It's A Crammed, Crammed World! 2 Country: Greece Released: 1989 Style: Synth-pop, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1577 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1512 mb WMA version RAR size: 1415 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 943 Other Formats: MPC MMF VOX MOD AHX MP1 AU Tracklist Hide Credits The Traitor A1 –Minimal Compact Producer – Colin NewmanRemix – Gilles Martin, Marc Hollander Atlantis A2 –Tuxedomoon Producer – Gilles MartinRemix – Frankie Lievaart Wedding With God A3 –Sonoko Producer – Marc HollanderRemix – Vincent Kenis New York A4 –Volti Mixed By – Gilles Martin, Marc HollanderProducer – Geordie Gillespie Nostalgie A5 –Zazou Bikaye Producer – Marc Hollander Bolingo A6 –Poto Doudongo* Producer – Vincent Kenis But I... B1 –Colin Newman Producer – Gilles Martin –Sussan Deihim* & Richard B2 Got Away Horowitz B3 –Bel Canto Agassiz Les Memes Histoires B4 –Karl Biscuit Producer – Gilles Martin B5 –John Lurie The Lampposts Are Mine B6 –Mahmoud Ahmed Sidetegnash Negn Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Crammed Discs Copyright (c) – Minos Notes (P) 1987 CRAMMED DISCS / (P)1989 MINOS Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: AEPI Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year It's A Crammed, CRAM 053 Various Crammed World! 2 Crammed Discs CRAM 053 Germany 1987 (LP, Comp) It's A Crammed, CRAM C 053 Various Crammed World! 2 Crammed Discs CRAM C 053 Belgium 1987 (Cass, Album, Comp) It's A Crammed, CRAM 053, Crammed Discs, CRAM 053, Various Crammed World! 2 Belgium 1987 cram 053 Crammed Discs cram 053 (LP, Comp) It's A Crammed, Tokuma Japan 32CRD-101 Various Crammed World! 2 32CRD-101 Japan 1988 Communications (CD, Comp) Related Music albums to It's A Crammed, Crammed World! 2 by Various Minimal Compact - Live Zazou Bikaye - Mr. -

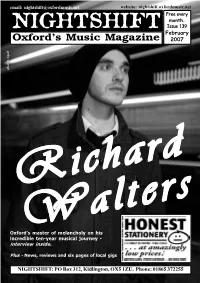

Issue 139.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 139 February Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 photo by Squib RichardRichardRichard Oxford’sWaltersWaltersWalters master of melancholy on his incredible ten-year musical journey - interview inside. Plus - News, reviews and six pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS photo: Matt Sage Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] BANDS AND SINGERS wanting to play this most significant releases as well as the best of year’s Oxford Punt on May 9th have until the its current roster. The label began as a monthly 15th March to send CDs in. The Punt, now in singles club back in 1997 with Dustball’s ‘Senor its tenth year, will feature nineteen acts across Nachos’, and was responsible for The Young six venues in the city centre over the course of Knives’ debut single and mini-album as well as one night. The Punt is widely recognised as the debut releases by Unbelievable Truth and REM were surprise guests of Robyn premier showcase of new local talent, having, in Nought. The box set features tracks by Hitchcock at the Zodiac last month. Michael the past, provided early gigs for The Young Unbelievable Truth, Nought, Beaker and The Stipe and Mike Mills joined bandmate Pete Knives, Fell City Girl and Goldrush amongst Evenings as well as non-Oxford acts such as Buck - part of Hitchcock’s regular touring others. Venues taking part this year are Borders, Beulah, Elf Power and new signings My band, The Venus 3 - onstage for the encores, QI Club, the Wheatsheaf, the Music Market, Device. -

The Tiger Time Out! Vol. 1 Issue 1 1994-01-20

Clemson's Guide to Entertainment & the Arts Volume I, No. 1 Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina January 20, 1994 Brooks Center Open! tME- OUT The Gathering Phridaz page 5 Erik Martin /interim head photographer Cayce Crenshaw practices her flute playing in one of the Brook's Center practice rooms Performing arts dances into future , ^ , _P„JL... ^ <-™L- ^HHPH that a np.rfnrminj? arts Dr. Mark Hosier. "A good facility proves by Caroline■ Godbey Cook added that a performing arts the value of the performing arts, and the staff writer building has been envisioned for quite a long time, and recently the need was ad- arts are important to students no matter After six years of planning, numerous dressed by President Max Lennon. what your major is." The outside may not be so pleasing to The 2 Tone delays, and lots of talk, the Brooks Center Six years ago he met with campus the eye since the landscaping is not com- for the Performing Arts is finally open. planners and an outside consultant to plete, but the inside is a totally different Collection Located behind the Strom Thurmond In- project the program's needs. Approxi- story. "It's really nice once you're inside stitute and next to Lehotsky Hall, the mately 150 possible designs were submit- and have gotten around the mud," said Brooks Center will serve students who are ted from architectural firms all over the Birma Gainor, who is involved in chorus involved in music, drama and dance. As country, Cook said. The firm who submit- and has a music theory class in the Brooks The Melvins new home of these students, it will put ted the chosen design was Sert, Jackson them all together for the first time, bring- and Associates of Cambridge, Center. -

Toonzetters Tegendraadse Muziek Uit Een Nieuwe Werkplaats

Toonzetters Tegendraadse muziek uit een nieuwe werkplaats Listen to the silence, let it ring on Eyes, dark grey lenses frightened of the sun We would have a fine time living in the night, Left to blind destruction, Waiting for our sight Robert de Vaan 301111 DT4 KAL2 Toonzetters INHOUD (BLZ/HST/TITEL) 2 0. VOOR 3 1. JONGERENCULTUUR IN DE 20e EEUW:MASSA EN TEGENCULTUUR 4 2. PUNK 6 3. NEW WAVE 6 4. TONY WILSON 7 5 CLUBS 8 6. FACTORY RECORDS 9 7 JOY DIVISION 11 8. NEW ORDER 12 9. ACHTER 13 B1 BIJLAGE 1: ONAFHANKELIJKE LABELS IN DE JAREN 80 14 B2 BIJLAGE 2: FACTORY CATALOGUS 21 B3 BIJLAGE 3: BRONNNEN 0. VOOR Er bestaan in mijn optiek maar twee stromingen binnen de muziek, te weten goede en slechte. De goede is doorgaans authentiek en de gevoelens die Ian Curtis, frontman van Joy Division, bezong leken mij als tiener in de jaren 80 oprecht, hij had er niet voor niets een einde aan gemaakt. De muziek hoorde bij de stroming New Wave, waar ik actief onderdeel van werd . Generatie Nix, de naam die mijn generatie meekreeg, zou toch geen werk vinden en de atoomoorlog zou spoedig beginnen. I wear black on the outside because black is how I feel on the inside zei Morrisey en daar kan ik me tot op de dag van vandaag in vinden... In dit referaat ga ik op zoek naar mijn muzikale en sociale roots en naar de achtergronden van het verhaal van een bijzondere en alternatieve onderneming. New Wave, de stroming voor de subcultuur der alternatieven waarvan Ian Curtis pionier was, vond zijn oorsprong halverwege de jaren 70 in de tegendraadse Punk. -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Touch and Go…Magazine (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Sex Master…Squeeze (7/78) Surrender…Cheap Trick (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) I Wanna Be Sedated (megamix)…The Ramones (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) I See Red…Split Enz (12/78) Roxanne…The