Raymon Elozua: How to Make a Teapot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New York / December 2010 / December York / New Frontdesk New York Dining / Nightlife / Shopping / Culture / Maps

FrontDesk / New York / December 2010 New York Dining / Nightlife / Shopping / Culture / Maps December 2010 2010 D . Y U R M A N © EXCLUSIVELY AT THE TOW N HOUSE , MADISON & 6 3 R D 212 7 5 2 4 2 5 5 DAVIDYURMAN.COM NOTE EDITOR’S DORSET JUSTIN VIRGINIA SHANNON EDITOR-IN-CHIEF PHOTO: New York radiates magic throughout the holiday season. I know that sounds like a cliché. But if you’ve ever experienced our great city at this time of year, you know I’m right. With or without a fresh sprinkling of glimmering snow, NYC offers so much to do. Front Desk fills you in on the options, beyond the usual suspects (Rockefeller Center, the Radio City Christmas Spectacular), enumerating festive alt-holiday activities to help you make the most of the season (p. 26). Of course, you can always go the Top 5 Picks traditional route and spend your time here shopping for gifts. Luckily, top fashion X NEW PLAY: U2’s Bono houses have just opened some must-visit and the Edge scored the new stores for the occasion (p. 20). Spider-Man musical! If the cold weather gets the better of X NEW PERFORMANCES: you, stop into a cozy eatery for some soul- Alvin Ailey’s City Center warming nourishment. We point you season celebrates 50 toward the best new comfort-food spots years of “Revelations.” (p. 24) and offer the inside scoop on Mario X NEW STORE: The just- Batali’s mega–resto-market Eataly (p. 18). opened Michael Kors If you skew more naughty than nice, the boutique on Bleecker. -

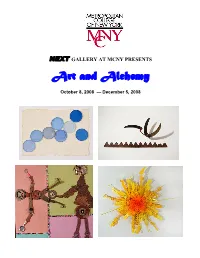

Art and Alchemy

NEXT GALLERY AT MCNY PRESENTS Art and Alchemy October 8, 2008 — December 5, 2008 About the show….. At one time or another almost everyone has found treasure in trash. We might be attracted to an object’s color, shape, or texture or simply an object’s ability to resonate emotionally with us. Each of the artist- alchemists in this exhibition uses found materials to transform waste into wonder. The term “Alchemy,” from the Arabic al-kīmiyā, originally referred to an investigation of nature combining elements of chemistry, physics, medicine, astrology, mysticism, and art. Alchemists throughout the ages sought to transform common metals into gold or silver, or find an elixir of life to cure all diseases and prolong life indefinitely. Today the term has come to mean any magical power or process of transmuting a common substance, usually of little value, into one of great value. Carol Goebel transforms rusted metal tools into beautiful installations that flicker with life and make you think you have come upon a flock of amazing flying creatures. Linda Stillman chooses found materials, remnants of daily life – coffee filters, tea bags, blossoms and bark from her garden and paint shards from her painting practice and transforms them into witty and elegant compositions. Elyse Taylor creates a charming and moving narrative patchwork of life experiences in her ongoing project, “Growing,” made up of 16 inch square panels, using a large variety of recycled and found materials along with paint and collage. Dan Walker transforms plastic parts by aggregating them according to color. His explosive assemblages and sculptures are dazzling in their intricacy and nuanced color relationships. -

424 Broome Street Brochure Digital.Indd

In the heart of SoHo between Lafayette and Crosby Streets, 424 Broome St. offers retailers the opportunity to join the world’s top luxury brands. The building’s ornate façade, complete with cast-iron finishes and stone flourishes, will be certain to draw in the plethora of tourists and locals who continuously visit SoHo – New York’s signature Downtown shopping neighborhood. 2,400 sf Ground Floor 1,600 sf Lower Level 4,000 sf Total Ground Floor Lower Level Mott St 424 Broome Street Retail Map Q3 2015 W Houston St Crosby St W Houston St Starbucks B D F M Keito Dos Caminos Trico Field Pop Galleries Russeck Gallery Ligne Roset Bulthaup Aroma Bunya CitiSpa ARI FLOS Desiron Jamba Juice Axelle Fine Arts Gallerie Porsche Design Dune Aesthetic Realism Available Vacant Cutler Foundation Billabong R by 45rpm Niko French Corner I Tre Merli Cappellini Costume National Stepevi Babette Kenneth Cole Portofino Sun Soho Wines & Spirits Mercer Parking Garage Duane Reade Eli Klein Fine Art add accesories Poltrona Frau Maclaren Moroso Leica Martin L Gallery Suglass Hut DTR Modern Galleries FLOR Think Pink Miro Cafe Aveda Compton Gallery Marni Mulberry St Billionaire Boys Club Halstead Property Blu Dot Diana von Versani Bank of America BK Indust. Thompson Furstenberg Kelley & Ping Haven Spa Esprit Alchemists Kisan Benefit Fred Perry AVAILABLE Zadig & Voltaire Versani Ricky’s AVAILABLE Warby Parker Brunello Cucinelli Verizon MercBar Broadway Gourmet Sportmax Proenza Schouler YSL hibba NYC (upstairs) Alessi/Taralucci e Vino J.F Rey Nine West Louis K. Prince St Meisel GalleryUno de CinquentaFolli FollieWink Sabon Club Monaco Michael Kors Crew Cuts The MercerKitchen Chobani Musette Prince St Aesop John Dellaria Salon Lacoste N R Vacant Nespresso Franklin B. -

The Pamphlet Files 1

The Pamphlet Files 1 The Pamphlet Files The Pamphlet Files were established as an original resource, part of the Library’s traditional and strong interest in the preservation of ephemera. Some of the material in these files dates back to the late nineteenth century. The Pamphlet Files are often the only record that a gallery or organization existed. They are not catalogued, and there are no references to them in our online catalogue. The files include exhibition brochures, fliers, small exhibition catalogues, gallery announcements, newsletters and other ephemera relating predominately to New York City and state galleries, museums, colleges and universities, professional associations, foundations, non-profit organizations, and other arts organizations. In addition, there are files for one-time arts events and movements, such as “New York State Exposition” and “Art for Peace.” Unless otherwise noted, all files originated from one of the five boroughs of New York City. The list of entries is arranged in alphabetical order; for galleries that have a given name and a surname, i.e. “Martha Jackson Gallery,” the entry will be alphabetized according to the first name. [A] [B] [C] [D] [E] [F] [G] [H] [I] [J] [K] [L] [M] [N] [O] [P] [Q] [R] [S] [T] [U] [V] [W] [X] [Y] [Z] Harriet Burdock Art & Architecture Collection ***Entries arranged by Serena Jimenez Updated and edited by Lauren Stark, 2010 The Pamphlet Files 2 A • A/D • A & M ARTWORKS • AARGAUER KUNSTHAUS • AARON BERMAN GALLERY • AARON FABER GALLERY • AARON FURMAN • ABC NO RIO • ABINGDON SQUARE PAINTERS • ACA GALLERY, 26 W. 8th St. & 52 W. -

NEST+Mauctioncatalog.07:Manhattan Auction.06

NEST+m PTA Gala & Auction APRIL 6, 2011 7:00 to 10:00pm at BRIDGEWATERS in the Bridge Room 11 Fulton Street atop the Fulton Market Building at South Street Seaport celebrating 10 years Dear NEST+m Parents, Faculty, and Friends: Welcome to the celebration of the 10th year of NEST+m! I always enjoy coming the PTA’s annual Gala & Auction where I see our community come together to celebrate the wonderful year we’ve had at school. Again, it has been a year in which our children have had great aca- demic success, inspired us with their musical and dramatic performances, and brought home championship trophies in chess, track & field and more! This evening’s festivities and the much-needed funds it will bring to our school are a testa- ment to the hard work of the parents and faculty of NEST+m. The room is filled with treas- ures made with love and a lot of effort by our students, and with offers of special treat experiences with the teachers, another sign of the warmth of our community. Bid generously on all of the things you’ve always wanted, from handbags to summer camp experiences for your kids. The businesses that donated want to see NEST+m raise as much money as possible. Thanks to your extraordinary generosity tonight and throughout the year, NEST+m can continue to offer a unique and exceptional educational experience for our children. The money raised by the PTA pays for so many things that would not be possible with the increas- ingly limited funds from Albany and the DOE. -

Rizzoliusa.Pdf

116 118 PREVIOUS SPREAD ROOTS, 2001 Cast bronze 12 × 16 × 14 ft. OPPOSITE DETAIL OF TRINITY ROOT, 2005 Cast bronze FOLLOWING SPREAD TRINITY ROOT, 2005 Cast bronze 13 × 15 × 20 ft. Installation at Trinity Church, corner of Wall Street and Broadway, New York, New York, 2005–2015 120 122 TRINITY ROOT, 2005 Cast bronze 13 × 15 × 20 ft. Installation at Trinity Church, corner of Wall Street and Broadway, New York, New York, 2005–2015 124 STEELROOT, 2008 Welded steel 50 × 35 × 40 ft. Installation view of Aerial Roots, Grounds for Sculpture, Hamilton, New Jersey, 2012 FOLLOWING SPREAD STEELROOT, 2011 Welded steel 21 × 19 × 34 ft. Installation view of Steelroots, 4th Shanghai Jing’ An International Sculpture Project (JISP), in front of the Shanghai Natural History Museum, Shanghai, China, 2016–2017 126 128 DETAIL OF STEELROOT Welded steel 130 STEELROOT, 2011 Welded steel 18 ft. × 12 ft. × 16 ft. 6 in.; 18 × 13 × 21 ft.; 20 × 10 × 16 ft. Installation view of Aerial Roots, Grounds for Sculpture, Hamilton, New Jersey, 2012 FOLLOWING SPREAD STEELROOT, 2007 Welded steel 10 ft. 6 in. × 12 ft. × 22 ft. Installation view, Wuhan, China 132 STEELROOT, 2009 Welded steel 15 × 15 × 18 ft. Installation view of Steelroots, Allentown Art Museum, Allentown, Pennsylvania, 2010 136 STEELROOT, 2011 Welded steel 10 × 17 × 11 ft. 138 STEELROOT, 2009 Welded steel 12 ft. 8 in. × 12 ft. 6 in. × 20 ft. FOLLOWING SPREAD Bending steel, John L. Lutz Welding & Fabrication, Frenchtown, New Jersey, 2012 140 142 STEELROOT, 2008 Welded steel 50 × 35 × 40 ft. Installation view of Exposed: The Secret Life of Roots, United States Botanic Gardens, Washington, D.C., 2015–2016 144 Steve Tobin fabricating a Steelroot, Prodex, Inc., Red Hill, Pennsylvania, 2007 FOLLOWING SPREAD STEELROOT, 2013 Welded steel 21 × 19 × 34 ft. -

A Finding Aid to the Ivan C. Karp Papers and OK Harris Works of Art Gallery Records, 1960-2014, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Ivan C. Karp Papers and OK Harris Works of Art Gallery Records, 1960-2014, in the Archives of American Art Catherine S. Gaines and Joy Goodwin 2014 October 17 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Historical note.................................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1960-2013.................................................................... 5 Series 2: Administrative Files, 1969-2014................................................................ 9 Series 3: Exhibition Files, 1969-2014................................................................... -

The Princeton University Art Museum

PrincetonUniversity DEPARTMENT OF Art Archaeology & Newsletter Dear Friends and Colleagues: SPRING We have had a busy year! On great figure of the department, Wen Fong, was Inside honored with a two-day symposium arranged by the faculty front we welcomed our the very active Tang Center. new Americanist, Rachael DeLue, There is news on other fronts, too. This is a FACULTY NEWS who came to us from the University self-study year—our first in over a decade—which has already prompted several adjustments to the of Illinois. Her task is a formidable undergraduate curriculum. Our introductory VISUAL ARTS FACULTY one—to replace the irreplaceable course will now be two—Art 100, from antiquity through the medieval period, and Art 101, from John Wilmerding, who retires in the Renaissance to contemporary art—but it will GRADUATE STUDENT NEWS spring 2007—but she has already remain team-taught. We will present a wide array displayed her great capabilities. of freshman and sophomore seminars to attract even more majors, and these new concentrators will UNDERGRADUATE NEWS This fall we will welcome our new medievalist, encounter a refashioned junior seminar on art-his- Nino Zchomelidse, who arrives from the Univer- torical methodology, with the option of a seminar sity of Tübingen, and we will also conduct a search focused on archaeological interpretation. The PUBLICATIONS in Japanese art, as Yoshiaki Shimizu has announced Senior Comprehensive exams will now be tailored his retirement as of spring 2009. This search will to the specific curricu- be followed by one in lum of each major. Northern Renaissance CONFERENCES Other proposals, art, so our lively pace too numerous to note will continue. -

Soho: Beyond Boutiques and Cast Iron the Significance, Legacy, and Preservation of the Pioneering Artist Community’S Cultural Heritage

(Left) Residents Exposing Brick Wall in Loft, Broome Street, SoHo, New York City, circa 1970. Photo Dorothy Koppelman, SoHo Memory Project. (Right) Bill Tarr, Door, Galvanized Steel, late 1960s, 102 Greene Street, SoHo, New York City. Photo by Author, 2012. SoHo: Beyond Boutiques and Cast Iron The Significance, Legacy, and Preservation of the Pioneering Artist Community’s Cultural Heritage Susie Ranney 2012 Historic Preservation Masters Thesis, Columbia University Advisor: Paul Bentel Table of Contents Thesis Abstract Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Synopsis of Significance 4 General Background 5 Urban Historical Significance 7 Aesthetic Significance 12 Cultural Significance 19 Chapter Conclusions 23 Chapter 2: The Artists’ SoHo 24 Preconditions of the SoHo Landscape 25 Heritage: Aesthetic Culture of the Early Artists’ SoHo 28 Aesthetics: From “Loft Dwelling” to “Loft Living” 29 Heritage: Collective Identity Rooted in Art and Landscape 39 Chapter Conclusions 50 Chapter 3: Evaluation of Preservation in SoHo 51 Official Preservation Intervention 52 Pursuing Municipal District Designation 52 SoHo-Cast Iron Historic District Designation Reports 54 Aftermath of Government Intervention 56 SoHo-Cast Iron Historic District Extension (2010) 58 Rise of Cultural Heritage Perservation 62 Factors Hindering Preservation of Artist Communities’ Cultural Heritage 65 Preservation Opportunties 70 Revising and Augmenting the Preservation Toolkit 74 Chapter Conclusions 77 Thesis Conclusions 78 Works Cited 81 Appendices 84 Acknowledgements and Dedication 99 SoHo: Beyond Boutiques and Cast Iron Thesis Abstract Fifty years ago, though the buildings stood, “SoHo” did not yet exist in name or concept. Instead, the area referred to by some as “Hell’s Hundred Acres” was considered to be a dying, industrial relic filled with unappealing buildings. -

169 Mercer Street Soho

169 MERCER STREET SOHO FEATURES ABOUT THIS PROPERTY TOTAL SF 4,200SF UNPARALLELED LOCATION: Embodying the charm and elegance that has made GROUND FLOOR: 2,400SF SoHo famous, 169 Mercer St. presents a unique opportunity in an area where LOWER LEVEL: 1,800SF space rarely becomes available. FRONTAGE TRENDY NEIGHBORHOOD: Mercer Street is filled with chic and trendy retailers. MERCER STREET 30’ Neighboring stores include Versace, Marni, Marc Jacobs, Dolce & Gabbana, Balenciaga, Prada, and Mercer Hotel. HIGHLIGHTS EXCELLENT RETAIL OPPORTUNITY: 169 Mercer St., located between Prince •TYPE: RETAIL Street and West Houston, offers 4,200 SF of retail space spread across the •TOTAL SF: 4,200SF ground floor and lower level. The property boasts furnished interiors, hardwood •MARKET: SOHO flooring, and specialty finishes including granite block and stone tiles. With 2,400 SF on the ground floor and 1,800 SF on the lower level, the property is perfectly suited for a tenant looking to make a mark in SoHo. 25 West 39th Street New York, NY 10018 Phone (212) 529-5055 FAX (212) 460-5362 169 MERCER STREET Mott St SOHO S R Crosby St W Houston St W Houston St Starbucks B D F M Keito Dos Caminos Trico Field REI Russeck Gallery Ligne Roset Bulthaup Development Aroma Site Vacant ARI FLOS Cassina Axelle Fine Arts Gallerie Porsche Design Tui Lifestyle Construction Site 24 Hour Fitness AVAILABLE Vacant Cutler R by 45rpm Billabong Seraphine Sadelle’s Cappellini Pomegranate Costume National Del Toro Stepevi Gallery Kenneth Cole Portofino Sun Soho Wines & Spirits Keneth Cole Development Mercer Parking Garage Duane Reade Housing Works Georges Bergés Gallery add accesories Poltrona Frau Site Moroso Leica Martin L Gallery Suglass Hut DTR Modern Galleries FLOR Think Pink Catch NY Aveda Giggle Marni Mulberry St Billionaire Boys Club Blu Dot Vera Wang Halstead Property Diana von Versani Bank of America Furstenberg Allouche Gallery Kelley & Ping Revolver Salon Thompson Haven Spa BK Indust. -

Athena Tacha: an Artist's Library on Environmental Sculpture and Conceptual

ATHENA TACHA: An Artist’s Library on Environmental Sculpture and Conceptual Art 916 titles in over 975 volumes ATHENA TACHA: An Artist’s Library on Environmental Sculpture and Conceptual Art The Library of Athena Tacha very much reflects the work and life of the artist best known for her work in the fields of environmental public sculpture and conceptual art, as well as photography, film, and artists’ books. Her library contains important publications, artists’ books, multiples, posters and documentation on environmental and land art, sculpture, as well as the important and emerging art movements of the sixties and seventies: conceptual art, minimalism, performance art, installation art, and mail art. From 1973 to 2000, she was a professor and curator at Oberlin College and its Art Museum, and many of the original publications and posters and exhibition announcements were mailed to her there, addressed to her in care of the museum (and sometimes to her colleague, the seminal curator Ellen Johnson, or her husband Richard Spear, the historian of Italian Renaissance art). One of the first artists to develop environmental site-specific sculpture in the early 1970s. her library includes the Berlin Land Art exhibition of 1969, a unique early “Seed Distribution Project” by the land and environmental artist Alan Sonfist, and a manuscript by Patricia Johanson. The library includes important and seminal exhibition catalogues from important galleries such as Martha Jackson’s “New Forms-New Media 1” from 1960. Canadian conceptual art is represented by N.E Thing, including the exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada, and the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design Projects Class cards, both in 1969. -

Eugene Brodsky CV

Eugene Brodsky CV Born 1946 New York, NY ONE PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2020 Winter Selections, Sears-Peyton Gallery, New York, NY 2017 Takes & Outtakes, Sears-Peyton Gallery, New York, NY 2016 Studio 11, East Hampton, NY 2015 Studio 11, East Hampton, NY 2014 Plans, Sears-Peyton Gallery, New York, NY 2011 Sears-Peyton Gallery, New York, NY 2009 Sears-Peyton Gallery, New York, NY 2006 Sears-Peyton Gallery, New York, NY 2005 Gallery Camino Real, Boca Raton, FL 2005 Butler Fine Arts, East Hampton, NY 2004 Imago Gallery, Palm Desert, CA 2003 Sears-Peyton Gallery, New York, NY 2003 Galerie 22, Hamburg, Germany 2001 Sears-Peyton Gallery, New York, NY 2001 Imago Galleries, Palm Desert, CA 2000 Roseline Koener Gallery, Westhampton, NY 1999 Gallery Camino Real, Boca Raton, FL 1998 Fassbender Gallery, Chicago, IL 1996 Fassbender Gallery, Chicago, IL 1995 Gallery Camino Real, Boca Raton, FL 1993 David Klein Gallery, Birmingham, MI 1992 David Klein Gallery, Birmingham, MI OK Harris Gallery (David Klein), Birmingham, MI 1991 OK Harris Gallery, New York, NY OK Harris Gallery, Birmingham, MI 1989 OK Harris Gallery, New York, NY 1988 OK Harris Gallery, New York, NY 1987 Grayson Gallery and Struve Gallery, Chicago, IL 1986 OK Harris Gallery, New York, NY Grayson Gallery, Chicago, IL 1985 OK Harris Gallery, New York, NY* 1983 OK Harris Gallery, New York, NY 1982 Jorgensen Gallery, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT (Catalogue Essay by Peter Frank) 1981 OK Harris Gallery, New York, NY 1977 Cunningham Ward Gallery, New York, NY 1976 Cunningham Ward Gallery, New York, NY GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2014 Ille Arts Paper and Canvas in Conversation, Amangansett, NY 2012 Sears-Peyton Gallery “Float”, New York, NY 2011 Sears-Peyton Gallery, New York, NY 2009 Lehman College Art Gallery, Bronx, NY 2008 Butler Fine Arts, East Hampton NY 2007 Imago Galleries, Palm Desert Ca 2007 Sears-Peyton Gallery, New York, NY 2005 Sears-Peyton Gallery, New York, NY 2004 Lehman College Art Gallery, Bronx,N.Y.