Colour Field’: a Reframing.” in David Moos, Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patel Spring 2017 GL ARH 4470 Syllabus

Do not copy without the express written consent of the instructor. Syllabus Spring 2017 ARH 4470/ARH 5482 Contemporary Art A Discipline-Specific Global Learning Course1 Tuesday and Thursday 2-3:15pm Green Library, Room 165 Instructor: Dr. Alpesh Kantilal Patel Assistant Professor, Contemporary Art and Theory Director, MFA in Visual Arts Affiliate Faculty, Center for Women’s and Gender Studies Affiliate Faculty, African and African diaspora Program Contact information for instructor: Department of Art + Art History MM Campus, VH 235 Preferred mode of contact: [email protected] Office hours: Thursday: 12:45-1:45pm Course description: This course examines major artists, artworks, and movements after World War II; as well as broader visual culture—everything from music videos and print advertisements to propaganda and photojournalism—especially as the difference between ‘art’ and non-art increasingly becomes blurred and the objectivity of aesthetics is called into question. Movements studied include Abstract Expressionism, Pop, and Minimalism in the 1950s and 1960s; Post-Minimalism/Process Art, and Land art in the late 1960s and 1970s; Pastiche/Appropriation and rise of interest in “identity” in the 1980s; and the emergence of Post-Identity, Relational Art, Internet/New Media art, and Post- Internet art in the 1990s/post-2000 period. This course will explore the expansion of the art world beyond “Euro- America.” In particular, we will consider the shift from an emphasis on the international to transnational. We will focus not only on artistic production in the US, but also that in Europe, South and East Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. -

Teaching Strategies: How to Explain the History and Themes of Abstract Expressionism to High School Students Using the Integrative Model

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Honors Theses Undergraduate Research 2014 Teaching Strategies: How to Explain the History and Themes of Abstract Expressionism to High School Students Using the Integrative Model Kirk Maynard Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/honors Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Maynard, Kirk, "Teaching Strategies: How to Explain the History and Themes of Abstract Expressionism to High School Students Using the Integrative Model" (2014). Honors Theses. 92. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/honors/92 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. 2014 Kirk Maynard HONS 497 [TEACHING STRATEGIES: HOW TO EXPLAIN THE HISTORY AND THEMES OF ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM TO HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS USING THE INTEGRATIVE MODEL] Abstract: The purpose of my thesis is to create a guideline for teachers to explain art history to students in an efficient way without many blueprints and precedence to guide them. I have chosen to focus my topic on Abstract Expressionism and the model that I will be using to present the concept of Abstract Expressionism will be the integrated model instructional strategy. -

CLAES OLDENBURG by Barbara Rose, the First Comprehensive Treatment of Oldenburg's

No. 56 V»< May 31, 1970 he Museum of Modern Art FOR IMT4EDIATE RELEASE jVest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart (N.B. Publication date of book: September 8) CLAES OLDENBURG by Barbara Rose, the first comprehensive treatment of Oldenburg's life and art, will be published by The Museum of Modern Art on September 8, 1970. Richly illustrated with 224 illustrations in black-and-white and 52 in color, this monograph, which will retail at $25, has a highly tactile., flexible binding of vinyl over foam-rubber padding, making it a "soft" book suggestive of the artist's well- known "soft" sculptures. Oldenburg came to New York from Chicago in 1956 and settled on the Lower East Side, at that time a center for young artists whose rebellion against the dominance of Abstract Expressionism and search for an art more directly related to their urban environment led to Pop Art. Oldenburg himself has been regarded as perhaps the most interesting artist to emerge from that movement — "interesting because he transcends it," in the words of Hilton Kramer, art critic of the New York Times. As Miss Rose points out, however, Oldenburg's art cannot be defined by the label of any one movement. His imagination links him with the Surrealists, his pragmatic thought with such American philosophers as Henry James and John Dewey, his handling of paint in his early Store reliefs with the Abstract Expressionists, his subject matter with Pop Art, and some of his severely geometric, serial forms with the Mini malists. -

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

Gallery-Guide-Off-Kilter For-Web.Pdf

Dave Yust, Circular Composition (#11 Round), 1969 UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR THE ARTS 1400 Remington Street, Fort Collins, CO artmuseum.colostate.edu [email protected] | (970) 491-1989 TUES - SAT | 10 A.M.- 6 P.M. THURSDAY OPEN UNTIL 7:30 P.M. ALWAYS FREE OFF KILTER, ON POINT ART OF THE 1960s FROM THE PERMANENT COLLECTION ABOUT THE COLLECTION Drawing on the museum’s longstanding strength in 20th-century art of the United States and Europe and including long-time visitor favorites and recent acquisitions, Off Kilter, On Point: Art of the 1960s from the Permanent Collection highlights the depth and breadth of artworks in the museum permanent collection. The exhibition showcases a wide range of media and styles, from abstraction to pop, presenting novel juxtapositions that reflect the tumult and innovations of their time. The 1960s marked a time of undeniable turbulence and strife, but also a period of remarkable cultural and societal change. The decade saw the civil rights movement and the Civil Rights Act, the Cuban missile crisis, the Vietnam conflict, political assassinations, the moon landing, the first televised presidential debate, “The Pill,” and, arguably, a more rapid rate of technological advancement and cultural change than ever before. The accelerated pace of change was well reflected in the art of the time, where styles and movements were almost constantly established, often in reaction to one another. This exhibition presents most of the major stylistic trends of art of the 1960s in the United States and Europe, drawn from the museum’s permanent collection. An art collection began taking shape at CSU long before there was an art museum, and art of the 1960s was an early focus. -

THE AMERICAN ART-1 Corregido

THE AMERICAN ART: AN INTRODUCTION Compiled by Antoni Gelonch-Viladegut For the Gelonch Viladegut Collection Paris-Boston, April 2011 SOMMARY INTRODUCTION 3 18th CENTURY 5 19th CENTURY 6 20th CENTURY 8 AMERICAN REALISM 8 ASHCAN SCHOOL 9 AMERICAN MODERNISM 9 MODERNIST PAINTING 13 THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST 14 HARLEM RENAISSANCE 14 NEW DEAL ART 14 ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM 15 ACTION PAINTING 18 COLOR FIELD 19 POLLOCK AND ABSTRACT INFLUENCES 20 ART CRITICS OF THE POST-WORLD WAR II ERA 21 AFTER ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM 23 OTHER MODERN AMERICAN MOVEMENTS 24 THE GELONCH VILADEGUT COLLECTION 2 http://www.gelonchviladegut.com The vitality and the international presence of a big country can also be measured in the field of culture. This is why Statesmen, and more generally the leaders, always have the objective and concern to leave for posterity or to strengthen big cultural institutions. As proof of this we can quote, as examples, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the British Museum, the Monastery of Escorial or the many American Presidential Libraries which honor the memory of the various Presidents of the United States. Since the Holy Roman Empire and, notably, in Europe during the Renaissance times cultural sponsorship has been increasingly active for the sake of art or for the sense of splendor. Nowadays, if there is a country where sponsors have a constant and decisive presence in the world of the art, this is certainly the United States. Names given to museum rooms in memory of devoted sponsors, as well as labels next to the paintings noting the donor’s name, are a very visible aspect of cultural sponsorship, especially in America. -

2013 Issue #5

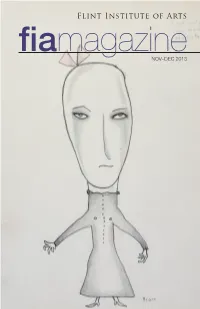

Flint Institute of Arts fiamagazineNOV–DEC 2013 Website www.flintarts.org Mailing Address 1120 E. Kearsley St. contents Flint, MI 48503 Telephone 810.234.1695 from the director 2 Fax 810.234.1692 Office Hours Mon–Fri, 9a–5p exhibitions 3–4 Gallery Hours Mon–Wed & Fri, 12p–5p Thu, 12p–9p video gallery 5 Sat, 10a–5p Sun, 1p–5p art on loan 6 Closed on major holidays Theater Hours Fri & Sat, 7:30p featured acquisition 7 Sun, 2p acquisitions 8 Museum Shop 810.234.1695 Mon–Wed, Fri & Sat, 10a–5p Thu, 10a–9p films 9–10 Sun, 1p–5p calendar 11 The Palette 810.249.0593 Mon–Wed & Fri, 9a–5p Thu, 9a–9p news & programs 12–17 Sat, 10a–5p Sun, 1p–5p art school 18–19 The Museum Shop and education 20–23 The Palette are open late for select special events. membership 24–27 Founders Art Sales 810.237.7321 & Rental Gallery Tue–Sat, 10a–5p contributions 28–30 Sun, 1p–5p or by appointment art sales & rental gallery 31 Admission to FIA members .............FREE founders travel 32 Temporary Adults .........................$7.00 Exhibitions 12 & under .................FREE museum shop 33 Students w/ ID ...........$5.00 Senior citizens 62+ ....$5.00 cover image From the exhibition Beatrice Wood: Mama of Dada Beatrice Wood American, 1893–1998 I Eat Only Soy Bean Products pencil, color pencil on paper, 1933 12.0625 x 9 inches Gift of Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, LLC, 2011.370 FROM THE DIRECTOR 2 I never tire of walking through the sacred or profane, that further FIA’s permanent collection galleries enhances the action in each scene. -

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

The Effect of War on Art: the Work of Mark Rothko Elizabeth Leigh Doland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 The effect of war on art: the work of Mark Rothko Elizabeth Leigh Doland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Doland, Elizabeth Leigh, "The effect of war on art: the work of Mark Rothko" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2986. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2986 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECT OF WAR ON ART: THE WORK OF MARK ROTHKO A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts in The Interdepartmental Program in Liberal Arts by Elizabeth Doland B.A., Louisiana State University, 2007 May 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………iii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………........1 2 EARLY LIFE……………………………………………………....3 Yale Years……………………………………………………6 Beginning Life as Artist……………………………………...7 Milton Avery…………………………………………………9 3 GREAT DEPRESSION EFFECTS………………………………...13 Artists’ Union………………………………………………...15 The Ten……………………………………………………….17 WPA………………………………………………………….19 -

Summer 1987 CAA Newsletter

newsletter Volume 12. Number 2 Summer 1987 1988 annual meeting studio sessions Studio sessions for the 1988 annual meeting in Houston (February Collusion and Collision: Critical Engagements with Mass 11-13) have been planned by Malinda Beeman, assistant professor, Culture. Richard Bolton, c! 0 Ha,rvard University Press, 79 University of Houston and Karin Broker, assistant professor, Rice Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138. University. Listed below are the topics they have selected. Anyaddi Art and mass culture: it is customary to think of these two as antagon tional information on any proposed session will be published in the Fall ists, with art kept apart to best preserve its integrity. But recent art and newsletter. Those wishing to participate in any open session must sub theory has questioned the necessity of this customary antagonism, and mit proposals to the chair of that session by October I, 1987. Note: Art many contemporary artists now regularly borrow images and tech history topics were announced in a special mailing in April. The dead niques from mass culture. This approach is fraught with contradic line for those sessions was 31 May. tions, at times generating critical possibility, at times only extending the reign of mass culture. It becomes increasingly difficult to distin Artists' Visions of Imaginary Cultures. Barbara Maria Stafford (art guish triviality from relevance, complicity from opposition, collusion historian). University of Chicago and Beauvais Lyons (print from collision. Has the attempt to redraw the boundaries between maker), University of Tennessee, Department of Art, 1715 Vol mass culture and art production been successful? Can society be criti unteer Blvd., Knoxville, TN 37996-2410. -

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Alice Aycock: Sculpture and Projects

Alice Aycock: Sculpture and Projects. Cambridge and London: M.I.T. Press, 2005; pp. 1-8. Text © Robert Hobbs The Beginnings of a Complex The problem seems to be how to connect without connecting, how to group things together in such a way that the overall shape would resemble "the other shape, ifshape it might be called, that shape had none," referred to by Milton in Paradise Lost, how to group things haphazardly in much the way that competition among various interest groups produces a kind ofhaphazardness in the way the world looks and operates. The problem seems to be how to set up the conditions which would generate the beginnings ofa complex. Alice Aycock Project Entitled "The Beginnings ofa Complex . ." (1976-77): Notes, Drawings, Photographs, 1977 In Book 11 of Milton's Paradise Lost, Death assumes the guise of two wildly dissimilar figures near Hell's entrance, each with an extravagantly inconsistent appearance. The first, a trickster, appears as a fair woman from above the waist and a series of demons below, while the second-a "he;' according to Milton-is far more elusive. It assumes "the other shape" that Aycock refers to above. 1 When searching for a poetic image capable of communicating the world's elusiveness and indiscriminate randomness, Aycock remembered this description of Death's incommensurability, which she then incorporated into her artist's book Project Entitled "The Beginnings ofa Complex . ." (1976-77): Notes, Drawings, Photographs. Although viewing death in terms oflife is certainly not an innovation, as anyone familiar with Etruscan and Greco-Roman culture can testify, seeing life's complexity in terms of this shape-shifting allegorical figure signaling its end is a remarkable poetic enlists images from the past and from other inversion.