Phylogenetic Inference and Trait Evolution of the Psychedelic Mushroom Genus Psilocybe Sensu Lato (Agaricales)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Squamanita Odorata (Agaricales, Basidiomycota), New Mycoparasitic Fungus for Poland

Polish Botanical Journal 61(1): 181–186, 2016 DOI: 10.1515/pbj-2016-0008 SQUAMANITA ODORATA (AGARICALES, BASIDIOMYCOTA), NEW MYCOPARASITIC FUNGUS FOR POLAND Marek Halama Abstract. The rare and interesting fungus Squamanita odorata (Cool) Imbach, a parasite on Hebeloma species, is reported for the first time from Poland, briefly described and illustrated based on Polish specimens. Its taxonomy, ecology and distribution are discussed. Key words: Coolia, distribution, fungicolous fungi, mycoparasites, Poland, Squamanita Marek Halama, Museum of Natural History, Wrocław University, Sienkiewicza 21, 50-335 Wrocław, Poland; e-mail: [email protected] Introduction The genus Squamanita Imbach is one of the most nita paradoxa (Smith & Singer) Bas, a parasite enigmatic genera of the known fungi. All described on Cystoderma, was reported by Z. Domański species of the genus probably are biotrophs that from one locality in the Lasy Łochowskie forest parasitize and take over the basidiomata of other near Wyszków (valley of the Lower Bug River, agaricoid fungi, including Amanita Pers., Cysto- E Poland) in September 1973 (Domański 1997; derma Fayod, Galerina Earle, Hebeloma (Fr.) cf. Wojewoda 2003). This collection was made P. Kumm., Inocybe (Fr.) Fr., Kuehneromyces Singer in a young forest of Pinus sylvestris L., where & A.H. Sm., Phaeolepiota Konrad & Maubl. and S. paradoxa was found growing on the ground, possibly Mycena (Pers.) Roussel. As a result the among grass, on the edge of the forest. Recently, host is completely suppressed or only more or less another species, Squamanita odorata (Cool) Im- recognizable, and the Squamanita basidioma is bach, was found in northern Poland (Fig. 1). -

CRISTIANE SEGER.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ CRISTIANE SEGER REVISÃO TAXONÔMICA DO GÊNERO STROPHARIA SENSU LATO (AGARICALES) NO SUL DO BRASIL CURITIBA 2016 CRISTIANE SEGER REVISÃO TAXONÔMICA DO GÊNERO STROPHARIA SENSU LATO (AGARICALES) NO SUL DO BRASIL Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Botânica, área de concentração em Taxonomia, Biologia e Diversidade de Algas, Liquens e Fungos, Setor de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Paraná, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em Botânica. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Vagner G. Cortez CURITIBA 2016 '«'[ir UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ UFPR Biológicas Setor de Ciências Biológicas ***** Programa de Pos-Graduação em Botânica .*•* t * ivf psiomD* rcD í?A i 0 0 p\» a u * 303a 2016 Ata de Julgamento da Dissertação de Mestrado da pos-graduanda Cristiane Seger Aos 13 dias do mês de maio do ano de 2016, as nove horas, por meio de videoconferência, na presença cia Comissão Examinadora, composta pelo Dr Vagner Gularte Cortez, pela Dr* Paula Santos da Silva e pela Dr1 Sionara Eliasaro como titulares, foi aberta a sessão de julgamento da Dissertação intitulada “REVISÃO TAXONÓMICA DO GÊNERO STROPHARIA SENSU LATO (AGARICALES) NO SUL DO BRASIL” Apos a apresentação perguntas e esclarecimentos acerca da Dissertação, a Comissão Examinadora APROVA O TRABALHO DE CONCLUSÃO do{a) aluno(a) Cristiane Seger Nada mais havendo a tratar, encerrou-se a sessão da qual foi lavrada a presente ata, que, apos lida e aprovada, foi assinada pelos componentes da Comissão Examinadora Dr Vagr *) Dra, Paula Santos da Stlva (UFRGS) Dra Sionara Eliasaro (UFPR) 'H - UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANA UfPR , j í j B io lo g ic a s —— — — ——— Setor de Ciências Biologicas *• o ' • UrPK ----Programa- de— Pós-Graduação em Botânica _♦ .»• j.„o* <1 I ‘’Hl /Dl í* Ui V* k P, *U 4 Titulo Mestre em Ciências Biológicas - Área de Botânica Dissertação “REVISÃO TAXONÔMICA DO GÉNERO STROPHARIA SENSU LATO (AGARICALES) NO SUL DO BR ASIL” . -

Phylogeny of the Pluteaceae (Agaricales, Basidiomycota): Taxonomy and Character Evolution

AperTO - Archivio Istituzionale Open Access dell'Università di Torino Phylogeny of the Pluteaceae (Agaricales, Basidiomycota): taxonomy and character evolution This is the author's manuscript Original Citation: Availability: This version is available http://hdl.handle.net/2318/74776 since 2016-10-06T16:59:44Z Published version: DOI:10.1016/j.funbio.2010.09.012 Terms of use: Open Access Anyone can freely access the full text of works made available as "Open Access". Works made available under a Creative Commons license can be used according to the terms and conditions of said license. Use of all other works requires consent of the right holder (author or publisher) if not exempted from copyright protection by the applicable law. (Article begins on next page) 23 September 2021 This Accepted Author Manuscript (AAM) is copyrighted and published by Elsevier. It is posted here by agreement between Elsevier and the University of Turin. Changes resulting from the publishing process - such as editing, corrections, structural formatting, and other quality control mechanisms - may not be reflected in this version of the text. The definitive version of the text was subsequently published in FUNGAL BIOLOGY, 115(1), 2011, 10.1016/j.funbio.2010.09.012. You may download, copy and otherwise use the AAM for non-commercial purposes provided that your license is limited by the following restrictions: (1) You may use this AAM for non-commercial purposes only under the terms of the CC-BY-NC-ND license. (2) The integrity of the work and identification of the author, copyright owner, and publisher must be preserved in any copy. -

Major Clades of Agaricales: a Multilocus Phylogenetic Overview

Mycologia, 98(6), 2006, pp. 982–995. # 2006 by The Mycological Society of America, Lawrence, KS 66044-8897 Major clades of Agaricales: a multilocus phylogenetic overview P. Brandon Matheny1 Duur K. Aanen Judd M. Curtis Laboratory of Genetics, Arboretumlaan 4, 6703 BD, Biology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, Wageningen, The Netherlands Worcester, Massachusetts, 01610 Matthew DeNitis Vale´rie Hofstetter 127 Harrington Way, Worcester, Massachusetts 01604 Department of Biology, Box 90338, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 Graciela M. Daniele Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biologı´a Vegetal, M. Catherine Aime CONICET-Universidad Nacional de Co´rdoba, Casilla USDA-ARS, Systematic Botany and Mycology de Correo 495, 5000 Co´rdoba, Argentina Laboratory, Room 304, Building 011A, 10300 Baltimore Avenue, Beltsville, Maryland 20705-2350 Dennis E. Desjardin Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, Jean-Marc Moncalvo San Francisco, California 94132 Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, Royal Ontario Museum and Department of Botany, University Bradley R. Kropp of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2C6 Canada Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84322 Zai-Wei Ge Zhu-Liang Yang Lorelei L. Norvell Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Pacific Northwest Mycology Service, 6720 NW Skyline Sciences, Kunming 650204, P.R. China Boulevard, Portland, Oregon 97229-1309 Jason C. Slot Andrew Parker Biology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, 127 Raven Way, Metaline Falls, Washington 99153- Worcester, Massachusetts, 01609 9720 Joseph F. Ammirati Else C. Vellinga University of Washington, Biology Department, Box Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, 111 355325, Seattle, Washington 98195 Koshland Hall, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-3102 Timothy J. -

Basidiomycota: Agaricales) Introducing the Ant-Associated Genus Myrmecopterula Gen

Leal-Dutra et al. IMA Fungus (2020) 11:2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s43008-019-0022-6 IMA Fungus RESEARCH Open Access Reclassification of Pterulaceae Corner (Basidiomycota: Agaricales) introducing the ant-associated genus Myrmecopterula gen. nov., Phaeopterula Henn. and the corticioid Radulomycetaceae fam. nov. Caio A. Leal-Dutra1,5, Gareth W. Griffith1* , Maria Alice Neves2, David J. McLaughlin3, Esther G. McLaughlin3, Lina A. Clasen1 and Bryn T. M. Dentinger4 Abstract Pterulaceae was formally proposed to group six coralloid and dimitic genera: Actiniceps (=Dimorphocystis), Allantula, Deflexula, Parapterulicium, Pterula, and Pterulicium. Recent molecular studies have shown that some of the characters currently used in Pterulaceae do not distinguish the genera. Actiniceps and Parapterulicium have been removed, and a few other resupinate genera were added to the family. However, none of these studies intended to investigate the relationship between Pterulaceae genera. In this study, we generated 278 sequences from both newly collected and fungarium samples. Phylogenetic analyses supported with morphological data allowed a reclassification of Pterulaceae where we propose the introduction of Myrmecopterula gen. nov. and Radulomycetaceae fam. nov., the reintroduction of Phaeopterula, the synonymisation of Deflexula in Pterulicium, and 53 new combinations. Pterula is rendered polyphyletic requiring a reclassification; thus, it is split into Pterula, Myrmecopterula gen. nov., Pterulicium and Phaeopterula. Deflexula is recovered as paraphyletic alongside several Pterula species and Pterulicium, and is sunk into the latter genus. Phaeopterula is reintroduced to accommodate species with darker basidiomes. The neotropical Myrmecopterula gen. nov. forms a distinct clade adjacent to Pterula, and most members of this clade are associated with active or inactive attine ant nests. -

The Mycological Society of San Francisco • Jan. 2016, Vol. 67:05

The Mycological Society of San Francisco • Jan. 2016, vol. 67:05 Table of Contents JANUARY 19 General Meeting Speaker Mushroom of the Month by K. Litchfield 1 President Post by B. Wenck-Reilly 2 Robert Dale Rogers Schizophyllum by D. Arora & W. So 4 Culinary Corner by H. Lunan 5 Hospitality by E. Multhaup 5 Holiday Dinner 2015 Report by E. Multhaup 6 Bizarre World of Fungi: 1965 by B. Sommer 7 Academic Quadrant by J. Shay 8 Announcements / Events 9 2015 Fungus Fair by J. Shay 10 David Arora’s talk by D. Tighe 11 Cultivation Quarters by K. Litchfield 12 Fungus Fair Species list by D. Nolan 13 Calendar 15 Mushroom of the Month: Chanterelle by Ken Litchfield Twenty-One Myths of Medicinal Mushrooms: Information on the use of medicinal mushrooms for This month’s profiled mushroom is the delectable Chan- preventive and therapeutic modalities has increased terelle, one of the most distinctive and easily recognized mush- on the internet in the past decade. Some is based on rooms in all its many colors and meaty forms. These golden, yellow, science and most on marketing. This talk will look white, rosy, scarlet, purple, blue, and black cornucopias of succu- at 21 common misconceptions, helping separate fact lent brawn belong to the genera Cantharellus, Craterellus, Gomphus, from fiction. Turbinellus, and Polyozellus. Rather than popping up quickly from quiescent primordial buttons that only need enough rain to expand About the speaker: the preformed babies, Robert Dale Rogers has been an herbalist for over forty these mushrooms re- years. He has a Bachelor of Science from the Univer- quire an extended period sity of Alberta, where he is an assistant clinical profes- of slower growth and sor in Family Medicine. -

Studies of Species of Hebeloma (FR.) KUMMER from the Great Lakes Region of North America I

©Verlag Ferdinand Berger & Söhne Ges.m.b.H., Horn, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Studies of Species of Hebeloma (FR.) KUMMER from the Great Lakes Region of North America I. *) Alexander H. SMITH Professor Emeritus, University Herbarium University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA Introduction The genus Hebeloma is a member of the family Cortinariaceae of the order Agaricales. In recent times it has emerged from relative taxonomic obscurity largely, apparently, because most of its species are thought to be mycorrhiza formers with our forest trees, and this phase of forest ecology is now much in the public eye. The genus, as recognized by SMITH, EVENSON & MITCHEL (1983) is essentially that of SINGER (1975) with some adjustments in the infrageneric categories recognized. It is also, the same, for the most part, as the concept proposed by the late L. R. HESLER in his unfinished manuscript on the North American species which SMITH is now engaged in completing. In the past there have been few treatments of the North American species which recognized more than a dozen species. MURRILL (1917) recognized 49 species but a number of these have been transferred to other genera. In the recent past, how- ever, European mycologists have showed renewed interest in the genus as is to be noted by the papers of ROMAGNESI (1965), BRUCHET (1970), and MOSER (1978). The species included here are some that have been observed for years by the author (1929—1983) in local localities, and the obser- vations on them have clarified their identity and allowed their probable relationships to be proposed. -

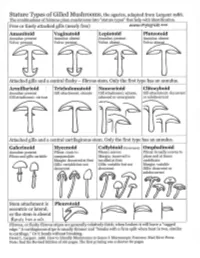

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

Version 1.1 Standardized Inventory Methodologies for Components Of

Version 1.1 Standardized Inventory Methodologies For Components Of British Columbia's Biodiversity: MACROFUNGI (including the phyla Ascomycota and Basidiomycota) Prepared by the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks Resources Inventory Branch for the Terrestrial Ecosystem Task Force, Resources Inventory Committee JANUARY 1997 © The Province of British Columbia Published by the Resources Inventory Committee Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Standardized inventory methodologies for components of British Columbia’s biodiversity. Macrofungi : (including the phyla Ascomycota and Basidiomycota [computer file] Compiled by the Elements Working Group of the Terrestrial Ecosystem Task Force under the auspices of the Resources Inventory Committee. Cf. Pref. Available through the Internet. Issued also in printed format on demand. Includes bibliographical references: p. ISBN 0-7726-3255-3 1. Fungi - British Columbia - Inventories - Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. BC Environment. Resources Inventory Branch. II. Resources Inventory Committee (Canada). Terrestrial Ecosystems Task Force. Elements Working Group. III. Title: Macrofungi. QK605.7.B7S72 1997 579.5’09711 C97-960140-1 Additional Copies of this publication can be purchased from: Superior Reproductions Ltd. #200 - 1112 West Pender Street Vancouver, BC V6E 2S1 Tel: (604) 683-2181 Fax: (604) 683-2189 Digital Copies are available on the Internet at: http://www.for.gov.bc.ca/ric PREFACE This manual presents standardized methodologies for inventory of macrofungi in British Columbia at three levels of inventory intensity: presence/not detected (possible), relative abundance, and absolute abundance. The manual was compiled by the Elements Working Group of the Terrestrial Ecosystem Task Force, under the auspices of the Resources Inventory Committee (RIC). The objectives of the working group are to develop inventory methodologies that will lead to the collection of comparable, defensible, and useful inventory and monitoring data for the species component of biodiversity. -

Agaricales, Hymenogastraceae)

CZECH MYCOL. 62(1): 33–42, 2010 Epitypification of Naucoria bohemica (Agaricales, Hymenogastraceae) 1 2 PIERRE-ARTHUR MOREAU and JAN BOROVIČKA 1 Faculté des Sciences Pharmaceutiques et Biologiques, Univ. Lille Nord de France, F–59006 Lille, France; [email protected] 2 Nuclear Physics Institute, v.v.i., Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Řež 130, CZ–25068 Řež near Prague, Czech Republic; [email protected] Moreau P.-A. and Borovička J. (2010): Epitypification of Naucoria bohemica (Agaricales, Hymenogastraceae). – Czech Mycol. 62(1): 33–42. The holotype of Naucoria bohemica Velen. has been revised. This collection corresponds to the most frequent interpretation of the taxon in modern literature. Since the condition of the material is not sufficient to determine microscopic and molecular characters, the authors designate a well-docu- mented collection from the same area (central Bohemia) and corresponding in all aspects with the holotype as an epitype. Description and illustrations are provided for both collections. Key words: Basidiomycota, Alnicola bohemica, taxonomy, typification. Moreau P.-A. a Borovička J. (2010): Epitypifikace druhu Naucoria bohemica (Agaricales, Hymenogastraceae). – Czech Mycol. 62(1): 33–42. Revidovali jsme holotyp druhu Naucoria bohemica Velen. Tato položka odpovídá nejčastější inter- pretaci tohoto taxonu v moderní literatuře, avšak není v dostatečně dobrém stavu pro mikroskopické a molekulární studium. Autoři proto stanovují jako epityp dobře dokumentovaný sběr pocházející ze stejné oblasti (střední Čechy), který ve všech aspektech odpovídá holotypu. Obě položky jsou dokumentovány popisem a vyobrazením. INTRODUCTION Naucoria bohemica Velen., a species belonging to a small group of ectomyco- rrhizal naucorioid fungi devoid of clamp connections [currently classified in the genus Alnicola Kühner, or alternatively Naucoria (Fr.: Fr.) P. -

Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area

Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area • Giuseppe Venturella Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area Edited by Giuseppe Venturella Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Diversity www.mdpi.com/journal/diversity Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area Editor Giuseppe Venturella MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editor Giuseppe Venturella University of Palermo Italy Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Diversity (ISSN 1424-2818) (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/diversity/special issues/ fungal diversity). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03936-978-2 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03936-979-9 (PDF) c 2020 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Editor .............................................. vii Giuseppe Venturella Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area Reprinted from: Diversity 2020, 12, 253, doi:10.3390/d12060253 .................... 1 Elias Polemis, Vassiliki Fryssouli, Vassileios Daskalopoulos and Georgios I. -

Revision of Pyrophilous Taxa of Pholiota Described from North America Reveals Four Species—P

Mycologia ISSN: 0027-5514 (Print) 1557-2536 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/umyc20 Revision of pyrophilous taxa of Pholiota described from North America reveals four species—P. brunnescens, P. castanea, P. highlandensis, and P. molesta P. Brandon Matheny, Rachel A. Swenie, Andrew N. Miller, Ronald H. Petersen & Karen W. Hughes To cite this article: P. Brandon Matheny, Rachel A. Swenie, Andrew N. Miller, Ronald H. Petersen & Karen W. Hughes (2018): Revision of pyrophilous taxa of Pholiota described from North America reveals four species—P.brunnescens,P.castanea,P.highlandensis, and P.molesta, Mycologia, DOI: 10.1080/00275514.2018.1516960 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00275514.2018.1516960 Published online: 27 Nov 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 28 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=umyc20 MYCOLOGIA https://doi.org/10.1080/00275514.2018.1516960 Revision of pyrophilous taxa of Pholiota described from North America reveals four species—P. brunnescens, P. castanea, P. highlandensis, and P. molesta P. Brandon Matheny a, Rachel A. Sweniea, Andrew N. Miller b, Ronald H. Petersen a, and Karen W. Hughesa aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee, Dabney 569, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996-1610; bIllinois Natural History Survey, University of Illinois Urbana Champaign, 1816 South Oak Street, Champaign, Illinois 61820 ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY A systematic reevaluation of North American pyrophilous or “burn-loving” species of Pholiota is Received 17 March 2018 presented based on molecular and morphological examination of type and historical collections.