A CASE of MATHARE and SOWETO SLUMS, NAIROBI •• Margaret N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Density and Spatial Patterns of Informal Settlements in Nairobi, Kenya

sustainability Article Population Density and Spatial Patterns of Informal Settlements in Nairobi, Kenya Hang Ren 1,2 , Wei Guo 3 , Zhenke Zhang 1,2,*, Leonard Musyoka Kisovi 4 and Priyanko Das 1,2 1 Center of African Studies, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210046, China; [email protected] (H.R.); [email protected] (P.D.) 2 School of Geography and Ocean Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China 3 Department of Social Work and Social Policy, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China; [email protected] 4 Department of Geography, Kenyatta University, Nairobi 43844, Kenya; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-025-89686694 Received: 21 August 2020; Accepted: 15 September 2020; Published: 18 September 2020 Abstract: The widespread informal settlements in Nairobi have interested many researchers and urban policymakers. Reasonable planning of urban density is the key to sustainable development. By using the spatial population data of 2000, 2010, and 2020, this study aims to explore the changes in population density and spatial patterns of informal settlements in Nairobi. The result of spatial correlation analysis shows that the informal settlements are the centers of population growth and agglomeration and are mostly distributed in the belts of 4 and 8 km from Nairobi’s central business district (CBD). A series of population density models in Nairobi were examined; it showed that the correlation between population density and distance to CBD was positive within a 4 km area, while for areas outside 8 km, they were negatively related. The factors determining population density distribution are also discussed. We argue that where people choose to settle is a decision process between the expected benefits and the cost of living; the informal settlements around the 4-km belt in Nairobi has become the choice for most poor people. -

Slum Toponymy in Nairobi, Kenya a Case Study Analysis of Kibera

Urban and Regional Planning Review Vol. 4, 2017 | 21 Slum toponymy in Nairobi, Kenya A case study analysis of Kibera, Mathare and Mukuru Melissa Wangui WANJIRU*, Kosuke MATSUBARA** Abstract Urban informality is a reality in cities of the Global South, including Sub-Saharan Africa, which has over half the urban population living in informal settlements (slums). Taking the case of three informal settlements in Nairobi (Kibera, Mathare and Mukuru) this study aimed to show how names play an important role as urban landscape symbols. The study analyses names of sub-settlements (villages) within the slums, their meanings and the socio-political processes behind them based on critical toponymic analysis. Data was collected from archival sources, focus group discussion and interviews, newspaper articles and online geographical sources. A qualitative analysis was applied on the village names and the results presented through tabulations, excerpts and maps. Categorisation of village names was done based on the themes derived from the data. The results revealed that village names represent the issues that slum residents go through including: social injustices of evictions and demolitions, poverty, poor environmental conditions, ethnic groupings among others. Each of the three cases investigated revealed a unique toponymic theme. Kibera’s names reflected a resilient Nubian heritage as well as a diverse ethnic composition. Mathare settlements reflected political struggles with a dominance of political pioneers in the village toponymy. Mukuru on the other hand, being the newest settlement, reflected a more global toponymy-with five large villages in the settlement having foreign names. Ultimately, the study revealed that ethnic heritage and politics, socio-economic inequalities and land injustices as well as globalization are the main factors that influence the toponymy of slums in Nairobi. -

PROF. GEORGE OKOYE KRHODA, CBS Department of Geography and Environmental Studies University of Nairobi P.O

PROF. GEORGE OKOYE KRHODA, CBS Department of Geography and Environmental Studies University of Nairobi P.O. Box 30197, 00100 Nairobi, KENYA Tel: +254 720 204 305; +254 733 454 216; +254 20-2017213 Fax: +254 020-2017213 Email: [email protected] PROFILE Prof. George Okoye Krhoda, CBS, is Associate Professor of Geography and Environmental Studies and Vice Chairman of the Daystar University Council. He is a Hydrologist/Water Resources Management specialist and has B.Ed.(Hons), M.A and Ph.D on River Hydraulics And Water Resources Planning. Krhoda is also the Managing Director of Research on Environment and Development Planning (REDPLAN) Consultants Ltd. Until December 2006, he was the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources and Chairman of the Negotiation Committee on the Nile Basin Cooperative Framework, and earlier Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Water and Irrigation where most of the water sector reforms were carried under his watch. Currently finalizing “Environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) for Akiira One Geothermal Power Energy in Rift Valley, having completed ESIA for Mount Suswa Geothermal Energy, Formulation of Kenya’s national Groundwater Policy; National Transboundary Water Resources Policy, and Outcome Evaluation of UNDP Rwanda Environment Programme”. Recently, Prof. Krhoda has been involved in “Development of the Mau Forest Complex Investment Programme”, “Lake Naivasha Conservation and Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) Programme” in developing, managing and evaluating -

GEORGE EVANS OWINO (P Department of Sociology, School Of

GEORGE EVANS OWINO (PH.D.- MAGNA CUM LAUDE) Department of Sociology, School of Humanities & Social Sciences, Kenyatta University P.O. Box 43844, 00100, Nairobi, Kenya. Office: +254 (0) 20 8710901 Ext. 4566 Cell-Phone: +254 (0) 722614878 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D University of Bielefeld, School of Public Health, May 2015 Major area: Experiences and Definitions of Health and Illness, Qualitative Research Methods, Public Health, Evidence-based Interventions. Dissertation Title: Illness Experiences of People Living with HIV in Kenya: A Case Study of Kisumu County. Chair: Prof. Dr. Alexander Krämer M.A. Kenyatta University, Department of Sociology, October 2005 Thesis Title: Preferences and Utilization of Health Care Services among Slum Residents in Kenya: A Case of Mathare Valley, Supervisor: Prof. Paul P. W. Achola B.A. Kenyatta University, Faculty of Arts, October 1997 Major subjects: Sociology & Religious Studies, Minor: Philosophy, communication skills, development studies. Languages English, German, Swahili, Dholuo SPECIALIZATION & RESEARCH INTERESTS Medical Sociology; Sociology of Health and Illness; Qualitative Health and Social Research Methods; Philosophy of Social Sciences; Health Systems Research; Monitoring and Evaluation; Evidence-Based Interventions, Early Childhood Development; Health Seeking Behaviour; HIV Prevention with Young People; Parent-Child Interaction Processes; Livelihoods. SCHOLASTIC HONOURS AND AWARDS 2012: Doctoral Scholarship, Sponsor: Kenyan-German Postgraduate Training -

Challenges of Strategy Implementation at Ecobank Kenya Limited

CHALLENGES OF STRATEGY IMPLEMENTATION AT ECOBANK KENYA LIMITED PHYLLIS AYUMA WETANGULA A MANAGEMENT RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION (MBA) DEGREE AT THE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI OCTOBER 2010 DECLARATION STUDENT’S DECLARATION I declare that this project is my original work and has never been submitted for a degree in any other university or college for examination/academic purposes. Signature: ……………………………………………..Date:………………………………… PHYLLIS AYUMA WETANGULA REG. NO: D61/70251/2008 SUPERVISOR’S DECLARATION This research project has been submitted for examination with my approval as the University Supervisor. Signature…………………………………….….Date………………………………….. JEREMIAH KAGWE LECTURER: UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI ii DEDICATION I dedicate this work in loving memory of my late parents Mr. David Habwe and Mrs. Ruth Asami Habwe who impressed on me the importance of education and encouraged me to pursue further studies. Mum, Dad, I miss you, but I am sure wherever you are, you are proud of me. I also dedicate this study to my loving husband Hon. Moses Wetang’ula and children, Sylvia, Eugene, Alvin, Fidel and Pauline who gave me enormous support financially and through encouragement, and sacrificed family time together to ensure I achieved my dream of obtaining a Masters Degree. May the Almighty God bless you all. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I take this opportunity to give thanks to the Almighty God for seeing me through the completion of this project. The work of carrying out this investigation needed adequate preparation and therefore called for collective responsibility of many personalities. The production of this research document has been made possible by invaluable support of many people. -

Appendix 1: Table of Confirmed Deaths and Alleged Perpetrators During Post-Election Violence in Nairobi, 2017 No Name Location Date Description of Status

Appendix 1: Table of Confirmed Deaths and Alleged Perpetrators During Post-Election Violence in Nairobi, 2017 No Name Location Date Description of Status . Violation 1 Francis Njuguna, Kariobangi, Nairobi August Shot dead Body found at 31 years old 11, 2017 City Mortuary 2 Vincent Omondi Dandora, Nairobi August Shot by police Died at Kenyatta Okebe, 27 years 11, 2017 National old Hospital 3 Thomas Dandora, August Shot inside his Died instantly Odhiambo Okul, Nairobi 11, 2017 gate by police 26 years old 4 Kevin Otieno, 23 Dandora, Nairobi August Shot outside Died on way to years old 12, 2017 his gate by hospital police 5 Vitalis Otieno, Dandora, Nairobi August Died of shock Died in his 24 years old 12, 2017 house 6 Sammy Amira Kawangware Stage August Hit by a Died at KNH on Loka, 45 years Two, Nairobi 9, 2017 teargas August 10, 2017 old canister – inhaled teargas 7 Lilian Khavere, Kawangware No.56, August Teargassed, Died at KNH 40 years old, 8 Nairobi 9, 2017 fell and months pregnant trampled by crowd 8 Festo Kevogo, 33 Kawangware No. 56, August Shot through Died on way to years old Nairobi 12, 2017 the head by hospital police 9 Melvin Mboka Satellite/Kawangware, August Shot dead by Body traced at Mwangitsi, 19 Nairobi 9, 2017 police KNH mortuary years old 10 Paul Mungai, 33 Kawangware No 56, August Shot in the Died from years old Nairobi 12, 2017 abdomen by internal bleeding at KNH police in his house 11 Zebedeo Kawangware No. 56, August Shot in the leg, Died at Mbagathi Mukhala, 42 Nairobi 12, 2017 fell and Hospital on years old trampled by August 14, 2017 crowd 12 Violet Khagai, 43 Kawangware Stage August Hit by teargas Died on way to years old Two, Nairobi 12, 2017 and inhaled hospital pepper spray 13 Eric Kwama, 30 Kawangware Stage August Hit by teargas Died at Kenyatta years old Two, Nairobi 10, 2017 fired at close National range, inhaled Hospital (KNH) pepper spray 14 Nelvin Amakove, Kawangware No. -

UN Habitat & Norwegian Government Visit Mukuru Sinai, Kenya

UN Habitat & Norwegian Government Visit Mukuru Sinai, Kenya L-R: Joan Clos (ED UN Habitat), Heikki Holmas (Min. Int'l Dev't, Gov't of Norway), and Robert (Muungano leader) tour the Mukuru Green Fields project. To read this article on the SDI Blog, please click here. NAIROBI, Kenya, November 13 | The Norwegian Minister for International Development, Heikki Holmas and UN-HABITAT Executive Director, Dr Joan Clos, visited Mukuru Kwa Njenga slums to share experiences with the slum dwellers as well as tour some of the ongoing projects such as the Mukuru Greenfields housing project. The two visited the settlement to offer encouragement to the Kenyan people living in slums and encouraged the communities to instill confidence and scope to some of the projects they are engaged in, under the stewardship of Muungano wa Wanavijiji. The visit was organized by UN-HABITAT, SDI, the Norwegian Embassy, and the Kenyan SDI Alliance: Muungano wa Wanavijiji, Akiba Mashinani Trust and Muungano Support Trust. Min. Holmas is received by founder of Mukuru Kwa Njenga settlement, Mr. Mzee Njenga. During the visit, Minister Heikki Holmas made the following statement: “The objective of the visit by representation of the Norwegian Government and UN-HABITAT to Mukuru slums is to give support and encouragement to the Kenyan people and the country’s institutions as it continues to bring about reforms in Kenyan land and housing. The right to own a home gives one and his family the opportunity to grow as a human being. There have been strong movements in Norway that campaign for home ownership. -

Mathare Slum

Standards of Living - Mathare Valley, Kenya Missions of Hope International Standards of Living - Mathare Slum Kenya is a beautiful country, well known for the many game parks and wild animals that abound throughout the country. However, Kenya is home to two of the largest slums in Africa, Kibera and Mathare. It is estimated that 800,000 people live in Mathare in an area of less than a square mile. Most live on an income of less than a dollar per day. Crime and HIV/AIDs are common. Many parents die of AIDS and leave their children to fend for themselves. Missions of Hope tries to care for as many of these orphans as possible, but their resources are limited. Mathare Facts: • 70% of Nairobi's population of four million lives on 5% of the of the city's land area. • Mathare contains a population greater than the cities of Seattle, Denver, or Boston, yet the slum covers an area of less than a square mile. In comparison, Seattle covers 142 square miles, Boston 89 square miles, and Denver 154 square miles. • 40% are HIV positive. • The average life expectancy for a person who is HIV positive in Mathare is five years or less. • Common health problems for children in Mathare include dysentery, malnutrition, malaria, typhoid, cholera, infections, tetanus, and polio. • Juvenile heads of households are common. (A child or teen is left to care for younger siblings, since both parents have died of AIDS.) Mathare has no police or fire protection, and no paved roads. • There are an estimated 70,000 children in the Mathare, with only 3-4 public schools to educate them. -

Nairobi Burning Kenya´S Post-Election Violence from the Perspective of the Urban Poor

PRIF-Report No. 110 Nairobi Burning Kenya´s post-election violence from the perspective of the urban poor Andreas Jacobs © Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) 2011 Correspondence to: PRIF (HSFK) x Baseler Straße 27-31 x 60329 Frankfurt am Main x Germany Telephone: +49(0)69 95 91 04-0 x Fax: +49(0)69 55 84 81 E-mail: [email protected] x Internet: www.prif.org ISBN: 978-3-942532-34-1 Euro 10,– Summary In the aftermath of the elections held in December of 2007, Kenya burst into flames. For nearly three months, the country was unsettled by a wave of ethno-political violence. This period of post-election violence saw more than a thousand Kenyans killed and between 300,000 and 500,000 internally displaced. Among the areas most heavily hit was the capi- tal city of Nairobi. Within Kenya’s political heart, the bulk of the violence took place in the slums. Life there was massively constrained by violent confrontations between follow- ers of Raila Odinga – leader of the oppositional Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) – and the police forces associated with the incumbent regime of President Mwai Kibaki and his Party for National Unity (PNU). At the same time, members of Kibaki’s ethnic com- munity, the Kikuyu, were selectively targeted by opposing groups. When fellow Kikuyu retaliated in the name of their peers, the flames of violence were fuelled even further. The PNU-ODM coalition government formed by President Kibaki and his challenger Odinga, in an attempt to end the violence at the end of February of 2008, has held until today. -

A Study on Quality of Life in Mathare, Nairobi, Kenya

© Kamla-Raj 2013 J Hum Ecol, 41(3): 207-219 (2013) A Study on Quality of Life in Mathare, Nairobi, Kenya Dan Darkey and Angela Kariuki Department of Geography, Geoinformatics and Meteorology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa KEYWORDS Quality of Life. Slum. Urbanisation. Nairobi ABSTRACT Sub-Saharan Africa hosts the highest number of urban slum households in the world with an estimated 60 to 70% of urban residents living in slums. Kenya belongs to this region and has large informal settlements with dire socio-economic conditions. This study on the quality of life, in a typical East African slum, is based on fieldwork carried out in Mathare, Nairobi. The research revealed that Mathare residents prioritise sanitation, waste management and access to water, electricity, education and healthcare as the most essential services for adding quality to their lives. However, one of the main conclusions of this research is that although improved service delivery is necessary, it may not be sufficient in satisfying the quality of life requirements of Mathare residents. Other aspects of economics, such as regular employment as well as socio-cultural issues, like freedom from fear and access to communal security, are equally important and policy objectives should pay holistic attention to both the objective living conditions and the subjective life satisfaction indicators of slum dwellers. INTRODUCTION rising costs of health care and education (UNDP 2007). The Roots of Socio-economic Inequality Many colonial laws and policies were enact- in Kenya ed to maintain the spatial segregation. Black people were not allowed to settle in urban areas, Kenya (see location of the country in Fig. -

List of Covid-Vaccination Sites August 2021

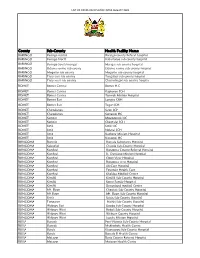

LIST OF COVID-VACCINATION SITES AUGUST 2021 County Sub-County Health Facility Name BARINGO Baringo central Baringo county Referat hospital BARINGO Baringo North Kabartonjo sub county hospital BARINGO Baringo South/marigat Marigat sub county hospital BARINGO Eldama ravine sub county Eldama ravine sub county hospital BARINGO Mogotio sub county Mogotio sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty east sub county Tangulbei sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty west sub county Chemolingot sub county hospital BOMET Bomet Central Bomet H.C BOMET Bomet Central Kapkoros SCH BOMET Bomet Central Tenwek Mission Hospital BOMET Bomet East Longisa CRH BOMET Bomet East Tegat SCH BOMET Chepalungu Sigor SCH BOMET Chepalungu Siongiroi HC BOMET Konoin Mogogosiek HC BOMET Konoin Cheptalal SCH BOMET Sotik Sotik HC BOMET Sotik Ndanai SCH BOMET Sotik Kaplong Mission Hospital BOMET Sotik Kipsonoi HC BUNGOMA Bumula Bumula Subcounty Hospital BUNGOMA Kabuchai Chwele Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma County Referral Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi St. Damiano Mission Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Elgon View Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma west Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi LifeCare Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Fountain Health Care BUNGOMA Kanduyi Khalaba Medical Centre BUNGOMA Kimilili Kimilili Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Korry Family Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Dreamland medical Centre BUNGOMA Mt. Elgon Cheptais Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Mt.Elgon Mt. Elgon Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Sirisia Sirisia Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Tongaren Naitiri Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Webuye -

The Case of Mlango Kubwa and Kawangware in Nairobi

African Review Vol. 44, No. 1, 2017: 27-61 Community-Led Security Mechanisms: The case of Mlango Kubwa and Kawangware in Nairobi Eva A. Maina Ayiera* Abstract The state assertion of monopoly over the provision of security and use of force remains a contested reality in Kenya. Challenges of inadequate finances, personnel and equipment limit the state’s capacity to secure the entire territory. The political economy allows for hierarchy in the provision of security and results in marginalisation of poor neighbourhoods and their security needs. Instead, they are seen as a source of insecurity and policing exerts a repressive hand. In the resulting lacuna, community-led security mechanisms emerge to provide security in poor neighbourhoods. The experience, successes and challenges of these mechanisms hold important lessons for policy-making on urban security. This paper presents the findings of a study assessing the effectiveness of community-led security mechanisms in two poor neighbourhoods in Nairobi and argues that nodal governance of security is the de-facto reality and indicates the trajectory of security governance in Kenya. Keywords: Security governance, poor urban neighbourhoods, Nairobi Introduction Public policing in Kenya and other nations in Africa has not succeeded in asserting monopoly over the provision of security and the use of force across the entire territory of the state (CHRIPS 2014). Often, a number of regions within the state remain underserved in the delivery of state security services. Inadequate financial resources and deficiency in security personnel numbers are among the key factors that limit state capacity to extend security services across the entire territory in Kenya and a number of countries in Africa.