The Trees of Arlington National Cemetery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Women and Their Families in the 19Th Century: Papers

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Research Collections in Women’s Studies General Editors: Anne Firor Scott and William H. Chafe Southern Women and Their Families in the 19th Century: Papers and Diaries Consulting Editor: Anne Firor Scott Series A, Holdings of the Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Parts 4–6: Nicholas Philip Trist Papers; Alabama, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida Collections; Virginia Collections Associate Editor and Guide Compiled by Martin P. Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Southern women and their families in the 19th century, papers, and diaries. Series A, Holdings of the Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill [microform] / consulting editor, Anne Firor Scott. microfilm reels. -- (Research collections in women’s studies) Accompanied by printed reel guide compiled by Martin P. Schipper. Contents: pt. 1. Mary Susan Ker Papers, 1785–1923 -- [etc.] -- pt. 5. Alabama, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida collections -- pt. 6. Virginia collections. ISBN 1-55655-417-6 (pt. 4 : microfilm) ISBN 1-55655-418-4 (pt. 5 : microfilm) ISBN 1-55655-419-2 (pt. 6 : microfilm) 1. Women--Southern States--History--19th century. 2. Family-- Southern States--History 19th century. I. Scott, Anne Firor, 1921– . II. Schipper, Martin Paul. III. Ker, Mary Susan, 1839–1923. IV. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library. Southern Historical Collection. V. University Publications of America (Firm). VI. Series. [HQ1458] 305.4′0975--dc20 91-45750 CIP Copyright © 1991 by University Publications of America. -

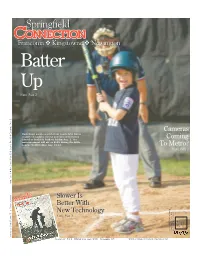

Springfieldspringfield

SpringfieldSpringfield FranconiaFranconia ❖❖ KingstowneKingstowne ❖❖ NewingtonNewington Batter Up News, Page 2 Cameras Classified, Page 15 Classified, Zach Keast awaits a pitch from coach John Burns ❖ as part of a public service announcement being Coming filmed at Trailside Park on Friday, Aug. 1. The announcement will air on ESPN during the Little League World Series, Aug. 15-24. To Metro? News, Page 2 Sports, Page 13 ❖ Real Estate, Page 12 Real Estate, ❖ Faith, Page 14 SlowerSlower IsIs insideinside BetterBetter WithWith Requested in home 8-8-08 Time sensitive material. NewNew TechnologyTechnology Attention Postmaster: /The Connection News,News, PagePage 33 U.S. Postage PRSRT STD PERMIT #322 Easton, MD PAID Sam Funt Photo by Photo Auguust 7-13, 2008 Volume XXII, Number 32 www.connectionnewspapers.com www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Springfield Connection ❖ August 9-13, 2008 ❖ 1 News Lights! Camera! Play Ball! TV spot will run during Little League World Series later this month. layers and coaches from the ball. Springfield Challenger Baseball Games are non-competitive, have two or P League had their Hollywood three innings and take place on Sunday af- moment on Friday, Aug. 1, as a ternoons. Challenger Baseball allows chil- crew filmed them at Trailside Park for a dren to socialize, develop skills, make public service announcement. friends and feel a sense of accomplishment. Little League Baseball and the Depart- Typically, each team has 10 or 11 players ment of Labor chose the Springfield Chal- and the league has 20 teams with over 200 lenger League to star in the television spot, players in the league. The league runs two which will air on ESPN Aug. -

Elly Doyle Park Service Awards Program | 2019

Fairfax County Park Authority EllyFairfax County Park AuthorityDoyle EllyPark ServiceDoyle Awards Park Service Awardsv November 22, 2019 Waterford at Fair Oaks v Chairman’s Choice Awards Harold L. Strickland Partnership and Collaboration Award Mayo Stuntz Cultural Stewardship Award Sally B. Ormsby Environmental Stewardship Award Fairfax County Park Foundation Eakin Philanthropy Awards Outstanding Volunteer Recognition Elly Doyle Park Service Awards Congratulations to all 2019 Award Recipients Program In the lobby reception area, enjoy the performance by Pianist Bob Boguslaw v Introductions Marguerite F. Godbold, Master of Ceremonies Sully District Representative Fairfax County Park Authority Board Welcoming Remarks & Presentation of Chairman’s Choice Awards William G. Bouie, Chairman Fairfax County Park Authority Board Presentation of the Harold L. Strickland Partnership and Collaboration Award John Foust, Dranesville District Supervisor Fairfax County Board of Supervisors Presentation of the Mayo Stuntz Cultural Stewardship Award Catherine Hudgins, Hunter Mill District Supervisor Fairfax County Board of Supervisors Presentation of the Sally B. Ormsby Environmental Stewardship Award Honorable Gerald Connolly, Congressman Virginia’s 11th Congressional District U.S. House of Representatives Presentation of the Fairfax County Park Foundation Eakin Philanthropy Awards Tim Eakin Walsh and Laura Eakin Erlacher Getting to Gold Kirk Kincannon, Executive Director Fairfax County Park Authority 2019 Outstanding Volunteers Awards Elly Doyle Youth Award Elly Doyle Special Recognition Awards Elly Doyle Park Service Awards v Chairman’s Choice Award Fairfax County Board of Supervisors Chairman, Sharon Bulova Board of Supervisors Chairman Sharon Bu- lova has been an ardent supporter of parks throughout more than 30 years of service on the Board of Supervisors, including 10 years as Board Chairman. -

Laurel Hill Laurel Hill

PRSRT STD U.S. Postage PAID Laurel Hill Elkton, MD PERMIT #31 Attention Postmaster: Time sensitive material. Requested in home 8-8-08 Lorton ❖ Lorton Valley ❖ Crosspointe National Night Out participants from the Southpointe Estates neighborhood in Lorton gather for a picture before indulging in the ice cream. Bottom row, from left, are: Taylor Plummer and Alex Jones; first row, Ann Van Houten, Allison Bruder, Kevin Mullins and Caitlin Mullins; second row, Bill Van Houtin, Jodi Clarken, Susan Mullins and Han Big Night Out Garcia; third row, Linda Bruder, Doug Bruder, Kyle Mullins, Santos Garcia and Mike Dragonette; and top row: News, Page 3 Jackson Plummer. insideinside Classified, Page 15 Classified, ❖ Faith, Page 13 ❖ Sports, Page 12 Cat Came Back News, Page 3 Top Marks For Cancer Center News, Page 4 Photo By Esther Pak/The Connection By Esther Photo www.connectionnewspapers.com www.ConnectionNewspapers.comAugust 7-13, 2008 Volume XXII, Number 32 Clifton/Fairfax Station/Laurel Hill Connection ❖ August 7-13, 2008 ❖ 1 News Feline, Lost and Found Blind therapy cat rescued after five-day search in Fairfax Station. By Rebecca Koenig and several have been eld- The Connection erly at the time of their adoption. To Davidson, the by Photo heodore was lost, and the rewards of welcoming an situation did not seem additional animal into her Tpromising. The blind cat, family make the work re- Rebecca Koenig a former therapy animal, quired to care for them escaped from his worthwhile. owner’s home on “It takes a great deal of “It’s nice to Thursday, July 24. -

MASTER LIST: FAIRFAX COUNTY INVENTORY of HISTORIC SITES Sorted by Supervisory Districts As of August 2021

MASTER LIST: FAIRFAX COUNTY INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES Sorted by Supervisory Districts As of August 2021 Status codes: * Indicates demolition of primary resource: potential intact archaeological components N National Register of Historic Places V Virginia Landmarks Register H Historic Overlay District L National Historic Landmark + Added to the Inventory of Historic Sites by the History Commission, but not yet included in tables in the Comprehensive Plan. Currently, the Comprehensive Plan shows the Inventory as of February 8, 2018 Red text includes other revisions that are not yet reflected in the Comprehensive Plan Braddock District Name Status Location Parcel Number Date Church of the Good Shepherd 5070 Twinbrook Run Drive 069-3 ((23)) 4 c. 1884-1888 Fairfax Church of the Holy Spirit 8800 Braddock Road 070-3 ((1)) 5 1966 Annandale Fairfax Villa Community Park East of Shirley Gate Road 056-4 ((6)) A, 39, c. 5000 BCE – between Route 29 and Braddock 40, 41, 42, 87A; Early 20th Road 057-3 ((1)) 1, 2; century 057-3 ((7)) A1 Little Zion Baptist Church and 10018 Burke Lake Road 077-4 ((1)) 14 1891 Cemetery Burke +National Bank of Fairfax 5234 Rolling Road, Burke 0694 01 0041C 1971-1972 Headquarters Building Oak Hill N, V 4716 Wakefield Chapel Road 070-1 ((16)) 285 c. 1790 Annandale Ossian Hall* 4957/5001 Regina Drive 070-4 ((6)) 124, c. 1783 Annandale 125 Ossian Hall Cemetery 7817 Royston Street 070-4 ((7)) 63 c. 1800 Annandale Wakefield Chapel 8415 Toll House Road 070-1 ((1)) 18 1897-1899 Annandale Dranesville District Name Status Location -

Ossian Hall Master Plan Revision

FAIRFAX COUNTY PARK AUTHORITY OSSIAN HALL MASTER PLAN REVISION Approved July 28, 2004 The Fairfax County Park Authority acknowledges the special efforts of the Ossian Hall Task Force members in developing the recommendations for this plan. O SSIAN H ALL P ARK ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Fairfax County Park Authority Ossian Hall Park Master Plan Revision July 2004 Park Authority Board Winifred S. Shapiro, Chairman, Braddock District Gilbert S. McCutcheon, Vice Chairman, Mt. Vernon District Jennifer E. Heinz, Secretary, At-Large Kenneth G. Feng, Treasurer, Springfield District Glenda M. Blake, Hunter Mill District Edward R. Batten, Sr., Lee District Kevin J. Fay, Dranesville District Georgette Kohler, At-Large George Lovelace, At-Large Joanne E. Malone, Providence District Harold L. Strickland, Sully District Frank S. Vajda, Mason District Senior Staff Michael A. Kane, Director Timothy K. White, Deputy Director Charlie Bittenbring, Acting Director, Park Services Division Brian Daly, Director, Park Operations Division Cindy Messinger, Director, Resource Management Division Miriam C. Morrison, Director, Administration Division Judy Pedersen, Public Information Officer Lynn S. Tadlock, Director, Planning & Development Division Project Team Angela, Allen, Park Planning Branch Todd Bolton, Resource Management Division Kelly Davis, Special Projects Branch Kirk Holley, Park Planning Branch Richard Maple, Park Operations Division Jenny Pate, Park Planning Branch Richard Sacchi, Resource Management Division P AGE 2 O SSIAN H ALL P ARK TABLE OF CONTENTS I. -

Alexandria Library, Special Collections Subject Index to Northern Virginia History Magazines

Alexandria Library, Special Collections Subject Index to Northern Virginia History Magazines SUBJECT TITLE MAG DATE VOL ABBEY MAUSOLEUM LAND OF MARIA SYPHAX & ABBEY MAUSOLEUM AHM OCT 1984 VOL 7 #4 ABINGDON ABINDGON MANOR RUINS: FIGHT TO SAVE AHM OCT 1996 V 10 #4 ABINGDON OF ALEXANDER HUNTER, ET. AL. AHM OCT 1999 V 11 #3 AMONG OUR ARCHIVES AHM OCT 1979 VOL 6 #3 ARLINGTON'S LOCAL & NATIONAL HERITAGE AHM OCT 1957 VOL 1 #1 LOST HERITAGE: EARLY HOMES THAT HAVE DISAPPEARED NVH FEB 1987 VOL 9 #1 VIVIAN THOMAS FORD, ABINGDON'S LAST LIVING RESIDENT AHM OCT 2003 V 12 #3 ABOLITION SAMUEL M. JANNEY: QUAKER CRUSADER NVH FEB 1981 VOL 3 #3 ADAMS FAMILY SOME 18TH CENTURY PROFILES, PT. 1 AHM OCT 1977 VOL 6 #1 AESCULAPIAN HOTEL HISTORY OF SUNSET HILLS FARM FHM 1958-59 VOL 6 AFRICAN-AMERICANS BLACK HISTORY IN FAIRFAX COUNTY FXC SUM 1977 VOL 1 #3 BRIEF HISTORY & RECOLLECTIONS OF GLENCARLYN AHM OCT 1970 VOL 4 #2 DIRECTOR'S CHAIR (GUM SPRINGS) AAVN JAN 1988 VOL 6 #1 GUM SPRINGS COMMUNITY FXC SPR 1980 VOL 4 #2 GUM SPRINGS: TRIUMPH OF BLACK COMMUNITY FXC 1989 V 12 #4 NEW MT. VERNON MEMORIAL: MORE THAN GW'S SLAVES FXC NOV 1983 VOL 7 #4 SOME ARL. AREA PEOPLE: THEIR MOMENTS & INFLUENCE AHM OCT 1970 VOL 4 #1 SOME BLACK HISTORY IN ARLINGTON COUNTY AHM OCT 1973 VOL 5 #1 UNDERGROUND RAILROAD ADVISORY COM. MEETING AAVN FEB 1995 V 13 #2 AFRICAN-AMERICANS-ALEXANDRIA ARCHAEOLOGY OF ALEXANDRIA'S QUAKER COMMUNITY AAVN MAR 2003 V 21 #2 AFRICAN-AMERICANS-ARCHAEOLOGY BLACK BAPTIST CEMETERY ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVEST AAVN AUG 1991 VOL 9 #8 CEMETERY DISCOVERIES AAVN FEB 1992 V 10 #2 -

VERTICAL FILE SUBJECT GUIDE DRAWER # 1 Abingdon African Americans a a Abolition a a Alexandria Museum Black History a @ Biograph

VERTICAL FILE SUBJECT GUIDE DRAWER # 1 Abingdon African Americans A A Abolition A A Alexandria Museum Black History A @ Biographies, 18th-19th Centuries A A Biographies, 20th Century A A Cemeteries " " Freedman’s Cemetery A A Demographic Studies A A Free Negroes A A Freedman=s Bureau A A Genealogy " " Heritage Tours, VA A A Historic Sites (Alexandria) A @ Pearl Incident 4/15/1848 A A Resources A A Revolutionary War A A Schools - Contraband Washington, DC Airports Alexandria Academy A Academy McGroarty Correspondence All-American City & Misc Slogans A Anniversary - #250 A Archives A Association A Bicentennial B 1949 A A Postage Stamp A A U. S. 1974 A Gazette A Historical Society A Library A A Company “ “ Sit-in, 1939 A Light Infantry A Sesquicentennial B 1899 Alleys Antiques Apothecary Shop Archaeology, 3 folders Architecture Arlington County Art and Artists Authors DRAWER # 2 Banks BIOGRAPHIES A A (misc) Adams Family Alexander Family Appich Family B B (misc) Bales, Richard Ball Family Barrett Family Blackbeard & the Pirate Booth Family Boothe, A Boush, Nathaniel Braddock, General Edward Brager Family Brenman, Ben Brent, Margaret Brent, Judge Samuel G. Broadwater, Charles Brown, William, Dr. Bryan, Daniel Burchell Burke Burke, Harry Burroughs C C (misc) Cameron, Baron of (see Fairfax Family) Carlyle, John Cates Family Cazenove Family Chapman, John G/Conrad W. Cone, Spencer H. Conger, Clement Conway, Richard Cooper, Samuel Corse, Montgomery Cox, Ethelyn Craik, Dr. Cranch, Judge William Custis Family Custis, Eliza Parke D D (misc) Daingerfield Family Dalton, John Davis, Gladys H. Davis, Samuel H. Dawkins, Nolan (Judge) Demaine Family Deneal Family Dermott, James DeVaughn, Samuel Dick, Dr. -

The Ravensworth Farmer Issue 7

The Official Publication of the Ravensworth Farm Civic Association, Inc. Springfield, Virginia May 2016 The Ravensworth Farmer Issue 7 SERVE IN YOUR COMMUNITY! GENERAL MEMBERSHIP CIVIC ASSOC. ELECTIONS MEETING, MAY 26 Elections for the Fall 2016-Summer 2017 Ravensworth Farm Civic Association board will be held Thursday, Thursday, May 26 @ 7:30PM May 26 during the General Meeting of the Civic Associ- Community of Christ Church on Inverchapel ation. While some members of the Board are able to serve again, there are several vacancies. Please consider Tyler Small, resident of Ravensworth Farm and serving on your Civic Associa- tion’s board. If you are interested professional home inspector, will talk about in serving, contact Kevin Joyce or maintenance and repair issues for our homes any other member of the current here in Ravensworth. Board for more information on the positions. Homeowners and renters in Ravensworth Farm are eligible IN THIS ISSUE to serve on the Board. Nominate an Environmental Hero, pg. 4 President - VACANT - Kevin Joyce stepping down as they prepare for the arrival of a little Joyce this summer Ravensworth Farms’ Own Farmers Market, pg. 8 1st Vice President - VACANT 2nd Vice President - Scott Houghton - willing to Pool News, pg. 8 serve again Treasurer - Heather Scott - willing to serve again History of Ravensworth PlantaƟon, pg. 9 Corresponding Secretary - VACANT Recording Secretary - Ginger Rogers - willing to Upcoming Events, pg. 17 serve again Coyote Awareness Tips, pg. 22 Article I, Section 3, of the Civic Association's By-Laws provides that the Association shall be strictly non-partisan, non-political, and non- sectarian. -

National Register Forms Template

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) (Expires Jan. 2005) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Oak Hill (029-0028) other names/site number 2. Location street & number 4716 Wakefield Chapel Road not for publication city or town Annandale vicinity state Virginia code VA county Fairfax code 059 zip code 22003 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally statewide X locally. -

Fairfax Serving High School Graduating Areas of Burke Class Throw Their Caps in Fairfax Areas of Burke the Air Following the Pre- Sentation of Their Diplomas

Members of the Fairfax Serving High School graduating Areas of Burke class throw their caps in Fairfax Areas of Burke the air following the pre- sentation of their diplomas. RainingRaining CapsCaps Commencement,Commencement, PagePage 1717 Classified, Page 26 Classified, ❖ Camps & Schools, Page 7 Camps & Schools, ❖ Faith, Page 24 ❖ Sports, Page 22 insideinside Requested in home 6-20-08 Time sensitive material. Attention Postmaster: U.S. Postage PRSRT STD PERMIT #322 Easton, MD Silverthorne’s Koger Firm PAID 18-Year Run Auctioned Off News, Page 3 News, Page 3 Photo By Sam Funt/The Connection Photo www.connectionnewspapers.com www.ConnectionNewspapers.com June 19-25, 2008 Volume XXII, Number 25 Fairfax Connection ❖ June 19-25, 2008 ❖ 1 2 ❖ Fairfax Connection ❖ June 19-25, 2008 www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Fairfax Connection Editor Michael O’Connell News 703-917-6440 or [email protected] 2 Cases, 2 Courts, Same Day Groner gave Koger his Jeffrey Koger appears in Miranda rights en route to court on attempted capital Inova Fairfax Hospital. “You are under arrest for murder of police officer. attempted capital murder Koger Firm Sold of a police officer,” Groner told Koger, who was admit- Sheriff’s Photo Sheriff’s By Ken Moore ted to the hospital in criti- Troubled management firm The Connection cal condition. On Tuesday, June 17, auctioned in bankruptcy court. effrey Scott Koger held a shotgun Judge Penney S. Azcarate against his shoulder and pointed the certified the case to a By Nicholas M. Horrock gun at Virginia State Trooper The Connection J Jeffrey Koger Fairfax grand jury, one of Jonathan Groner. -

Society of the Lees of Virginia

Society of the Lees of Virginia Collection, 1771-2000. 82 boxes, 264 A--264 CCCC (38 linear ft.). Biographical/Historical Note: The Society of the Lees of Virginia was established in 1921 by Cazenove Gardner Lee, Jr. and other members of the Lee family in order to: ...promote a better knowledge of the patriotic services of the Lee Family of Virginia to their country, to assist in the compiling of matter concerning periods of state, national and Lee family history; to mark, preserve, and restore historic sites of family interest; to draw together the widely scattered members of the Lee Family; to promote a wider feeling of fellowship among its members by means of social gatherings, pilgrimages and commemorative exercises. (From the Articles of Incorporation of the Society of the Lees of Virginia, 1961). The membership is composed of descendants of Col. Richard Lee, "The Emigrant," who settled in York County, Virginia, by 1642. Eleanor Lee Templeman (1906-1990), a Northern Virginia author, genealogist, and historian, assembled much of this collection. Her writings and correspondence capture the activities and interests of the Society, as well as the genealogy of the Lees. Scope and Content Note: This collection documents the family history of Lees in Virginia, especially to the Lees related to Richard Lee the Emigrant. There are extensive series of files by names of individuals with the surname of Lee, by surnames of other families which intermarried with the Lees, and by names of properties associated with these families. Other major series cover the English ancestry of the Lees, antique objects associated with the Lees, and the records of the Society of the Lees of Virginia.