Baesler on Kirsch, 'Proving Grounds: Project Plowshare and the Unrealized Dream of Nuclear Earthmoving'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duck and Cover: How Print Media, the U.S. Government, and Entertainment Culture Formedamerica's Understanding of the Atom

DUCK AND COVER: HOW PRINT MEDIA, THE U.S. GOVERNMENT, AND ENTERTAINMENT CULTURE FORMEDAMERICA’S UNDERSTANDING OF THE ATOM BOMB A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By Daniel Patrick Wright B.A., University of Cincinnati, 2013 2015 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL May 5, 2015 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Daniel Patrick Wright ENTITLED Duck and Cover: How Print Media, the U.S. Government and Entertainment Culture Formed America’s Understanding of the Atom Bomb BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts ________________________________ Jonathan Winkler, Thesis Director ________________________________ Carol Herringer, Chair History Department Committee on College of Liberal Arts Final Examination ________________________________ Drew Swanson, Ph.D. ________________________________ Nancy Garner, Ph.D. ________________________________ Robert E. W. Fyffe, Ph.D. Vice President for Research and Dean of the Graduate School ABSTRACT Wright, Daniel Patrick. M.A. Department of History, Wright State University, 2015. Duck and Cover: How Print Media, the U.S. Government and Entertainment Culture Formed America’s Understanding of the Atom Bomb This research project will explore an overview of the different subsections of American post-war society that contributed to the American “atomic reality” in hopes of revealing how and why the American understanding of atomic weapons did not slowly evolve over the course of a generation, but instead materialize rapidly in the years following the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. By analyzing government sources and programs, print media sources such as newspapers and magazines, and the American entertainment culture of the 1940s and 1950s, this research project will answer exactly why and how the American public arrived at its understanding of the atom bomb. -

Japan, the Atomic Bomb, and the “Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Power” 日本、原爆、「原子力の平和利用」•Japanese Translation Available

Volume 9 | Issue 18 | Number 1 | Article ID 3521 | May 02, 2011 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Japan, the Atomic Bomb, and the “Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Power” 日本、原爆、「原子力の平和利用」•Japanese translation available Yuki Tanaka, Peter J. Kuznick sense, a nuclear power accident can be seen as an “act of indiscriminate mass destruction,” Japan, the Atomic Bomb, and the and thus “an unintentionally committed crime “Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Power” against humanity.” Yuki Tanaka and Peter Kuznick It is well known that the origin of “the peaceful use of nuclear energy” was part of “Atoms for In this two part article Yuki Tanaka and Peter Peace,” a policy that U.S. President Dwight D. Kuznick explore the relationship between the Eisenhower launched at the U.N. General atomic bombing of Japan and that nation’s Assembly in December 1953. embrace of nuclear power, a relationship that may be entering a new phase with the 3.11 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear catastrophe at Fukushima. A Japanese translation by Noa Matsushita is available here. “The Peaceful Use of Nuclear Energy” and Hiroshima Yuki Tanaka The ongoing grave situation at the Fukushima No. 1 Nuclear Power Plant, which continues to contaminate vast areas of surrounding land and sea with high levels of radiation, forces us to reconsider the devastating impact of the so- called “peaceful use of nuclear energy” upon all forms of life, including human beings and Eisenhower addresses the UN General nature. The scale of damage to human beings Assembly, December 13, 1953 and the environment caused by a major accident at a nuclear power plant, where radiation is emitted either from the nuclear As Peter Kuznick concisely explains in the vessel or spent fuel rods, may be comparable to following article, what the U.S. -

Nuclear Weapons, Propaganda, and Cold War Memory Expressed in Film: 1959-1989 Michael A

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2016 Their swords, our plowshares: "Peaceful" nuclear weapons, propaganda, and Cold War memory expressed in film: 1959-1989 Michael A. St. Jacques James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Cultural History Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Political History Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Recommended Citation St. Jacques, Michael A., "Their swords, our plowshares: "Peaceful" nuclear weapons, propaganda, and Cold War memory expressed in film: 1959-1989" (2016). Masters Theses. 102. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/102 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Their Swords, Our Plowshares: "Peaceful" Nuclear Weapons, Propaganda, and Cold War Memory Expressed in Film: 1949-1989 Michael St. Jacques A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2016 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Dr. Steven Guerrier Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Maria Galmarini Dr. Alison Sandman Dedication For my wife, my children, my siblings, and all of my family and friends who were so supportive of me continuing my education. At the times when I doubted myself, they never did. -

The Discursive Emergence of Us Nuclear Weapons Policy

BUILDING MORE BOMBS: THE DISCURSIVE EMERGENCE OF US NUCLEAR WEAPONS POLICY by JOHN M. VALDEZ A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Political Science and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2018 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: John M. Valdez Title: Building More Bombs: The Discursive Emergence of US Nuclear Weapons Policy This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Political Science by: Jane K. Cramer Chair Gerald Berk Core Member Lars Skalnes Core Member Greg McLauchlan Institutional Representative and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2018. ii © 2018 John M. Valdez iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT John M. Valdez Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science June 2018 Title: Building More Bombs: The Discursive Emergence of US Nuclear Weapons Policy This dissertation investigates the social construction and discursive emergence of US nuclear weapons policy against the backdrop of the nuclear taboo and its associated anti-nuclear discourse. The analysis is drawn from poststructuralism with a focus on the discourses that construct the social world and its attendant “common sense,” and makes possible certain policies and courses of action while foreclosing others. This methodology helps overcome the overdetermined nature of foreign policy, or its tendency to be driven simultaneously by the international strategic environment, the domestic political environment, and powerful domestic organizations, and while being shaped and delimited by the discourses associated with the nuclear taboo. -

LLNL 65 Th Anniversary Book, 2017

Scientific Editor Paul Chrzanowski Production Editor Arnie Heller Pamela MacGregor (first edition) Graphic Designer George Kitrinos Proofreader Caryn Meissner About the Cover Since its inception in 1952, the Laboratory has transformed from a deactivated U.S. Naval Air Station to a campus-like setting (top) with outstanding research facilities through U.S. government investments in our important missions and the efforts of generations of exceptional people dedicated to national service. This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC, About the Laboratory nor any of their employees makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) was founded in 1952 to enhance process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to the security of the United States by advancing nuclear weapons science and any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise technology and ensuring a safe, secure, and effective nuclear deterrent. With does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States a talented and dedicated workforce and world-class research capabilities, the government or Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC. The views and opinions of authors expressed Laboratory strengthens national security with a tradition of science and technology herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. -

Subject Series, Alphabetical Subseries

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS WHITE HOUSE OFFICE, OFFICE OF THE STAFF SECRETARY: Records of Paul T. Carroll, Andrew J. Goodpaster, L. Arthur Minnich and Christopher H. Russell, 1952-61 Subject Series, Alphabetical Subseries CONTAINER LIST Box No. Contents 1 Governor Adams (1) [June 1953 - February 1956] [material re the President’s schedule; personnel matters; Commission on International Telecommunications; Rowland Hughes] Governor Adams (2) [March 1956] [Gov. Kohler of Wisconsin; federal appointments] Governor Adams (3) [May-October 1956] [1956 presidential campaign; Suez situation; Executive Pay-Retirement bill; Bricker amendment] Governor Adams (4) [November 1956 - February 1957] [federal appointments; OCB activities; foreign agricultural situation] Governor Adams (5) [April-May 1957] [Oxbow project; conflict between Sen. Anderson and Lewis Strauss; appropriations on an expenditure basis] Governor Adams (6) [June-November 1957] [Soviet propaganda; Idaho Power Co.; appropriation on an expenditure basis (H.R. 8002); appointment of Robert B. Anderson as Secretary of the Treasury] Governor Adams (7) [federal appointments; St. Lawrence Seaway opening; disarmament; National Science Foundation] Governor Adams (8) [April-September 1958] [Federal Aviation Agency; Lewis Strauss; Frances G. Knight; Leo Hoegh; Small Business Investment Act of 1958; copper-import taxes; Haiti] Administration Turnover [July-December 1960] (1)-(4) [material re transition between the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations] Administrative Arrangements (Denver - 1955) (1)-(3) [administrative operation of the WH staff during DDE’s convalescence in Denver] Administrative Vice President [January-March 1956] Advanced Research Projects Agency [January-August 1959] Agency Reports - Gold Directive [November 1960 - January 1961] (1)-(4) [material re Presidential directive of November 16, 1960 concerning balance of payments] Special Air Defense Study of Army Policy Council, Feb. -

Plowshare Report

DOE/NV/26383-22 CULTURAL RESOURCES TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 111 DIVISION OF EARTH AND ECOSYSTEM SCIENCES DESERT RESEARCH INSTITUTE LAS VEGAS, NEVADA THE OFF-SITE PLOWSHARE AND VELA UNIFORM PROGRAMS: Assessing Potential Environmental Liabilities through an Examination of Proposed Nuclear Projects, High Explosive Experiments, and High Explosive Construction Activities VOLUME 3 of 3 by Colleen M. Beck, Susan R. Edwards, and Maureen L. King with contributions by Harold Drollinger, Robert Jones, and Barbara Holz September 2011 Disclaimer This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors or their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or any third party’s use or the results of such use of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof or its contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. Available for sale to the public from: U.S. Department of Commerce National Technical Information Service 5301 Shawnee Road Alexandria, VA 22312 Phone: 800.553.6847 Fax: 703.605.6900 E-mail: [email protected] Online ordering: http://www.ntis.gov/help/ordermethods.aspx Available electronically at http://www.osti.gov/bridge Available for a processing fee to the U.S. -

United States Nuclear Testing Program Chronology

C EDR.BFS 3 893 UNITED STATES NUCLEAR TESTING PROGRAM CHRONOLOGY JUNE 18, 1992 U.S. NUCLEAR TESTING PROGRAM Chronology DATE EVENT January 1939 German scientists Hahn and Strassmann published results of their 1938 experiments with which they discovered the fission process. September 1, 1939 Nazi Germany Invaded Poland; World War II began. December 7 & 15, 1941 United States entered war with Japan and Germany, respectively. August 13, 1942 Manhattan Engineer District established to produce nuclear weapons. December 2, 1942 Physicists under direction of Enrico Fermi at the University of Chicago's Metallurgical Laboratory created the first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. March 15, 1943 Weapon laboratory established at Los Alamos, New Mexico. Now called Los Alamos National Laboratory. July 16, 1945 First atomic bomb, Trinitv, detonated at Alamogordo, New Mexico by the Manhattan Engineer District .r-'\ August6, 1~ First atomic bomb •UttJe Boy- dropped on Hiroshima, Japan. August 9, 1945 Second atomic bomb •Fat Man• detonated over Nagasaki, Japan. August 14, 1945 The government of Imperial Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration and surrendered. January 26, 1946 The United Nations General Assembly In London established the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission. June 14, 1946 Bernard Baruch, U.S. delegate to the U.N. Atomic Energy Commission, proposed a plan to outlaw the manufacture of atomic bombs, dismantle those already existing, and share atomic energy secrets with other nations. The Soviet Union rejected the plan and It failed. June-July 1946 The Manhattan Engineer District conducted Operation Crossroads, detonating two shots in the Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. August 1, 1946 Atomic Energy Act signed by President Truman established the Atomic Energy Commission and transferred the Army's Manhattan Engineer District atomic programs and facilities to the five member commission. -

Nevada Test Site – Site Description Effective Date: 05/27/2008 Type of Document TBD Supersedes: Revision 01

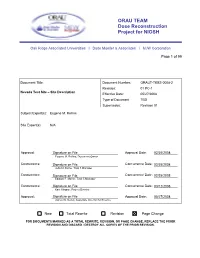

ORAU TEAM Dose Reconstruction Project for NIOSH Oak Ridge Associated Universities I Dade Moeller & Associates I MJW Corporation Page 1 of 99 Document Title: Document Number: ORAUT-TKBS-0008-2 Revision: 01 PC-1 Nevada Test Site – Site Description Effective Date: 05/27/2008 Type of Document TBD Supersedes: Revision 01 Subject Expert(s): Eugene M. Rollins Site Expert(s): N/A Approval: Signature on File Approval Date: 02/25/2008 Eugene M. Rollins, Document Owner Concurrence: Signature on File Concurrence Date: 02/25/2008 John M. Byrne, Task 3 Manager Concurrence: Signature on File Concurrence Date: 02/25/2008 Edward F. Maher, Task 5 Manager Concurrence: Signature on File Concurrence Date: 03/12/2008 Kate Kimpan, Project Director Approval: Signature on File Approval Date: 05/27/2008 James W. Neton, Associate Director for Science New Total Rewrite Revision Page Change FOR DOCUMENTS MARKED AS A TOTAL REWRITE, REVISION, OR PAGE CHANGE, REPLACE THE PRIOR REVISION AND DISCARD / DESTROY ALL COPIES OF THE PRIOR REVISION. Document No. ORAUT-TKBS-0008-2 Revision No. 01 PC-1 Effective Date: 05/27/2008 Page 2 of 99 PUBLICATION RECORD EFFECTIVE REVISION DATE NUMBER DESCRIPTION 02/02/2004 00 New technical basis document for the Nevada Test Site – Site Description. First approved issue with the restriction that states, “Nevada Test Site incidents are to be included in future revisions of the Nevada Test Site Technical Basis Documents.” Incorporates formal internal and NIOSH review comments. Initiated by Eugene M. Rollins. 10/01/2007 01 Approved Revision 01 initiated as a result of the biennial document review. -

The Plowshare Program

A Look Back: The Plowshare Program Login Contact Us Text Size: A Look Back: The Plowshare Program 06/19/2018 Likes(1) | Comments(2) | Printer-friendly Project Gnome, the first nuclear Plowshare experiment held Dec 10, 1961. High Resolution Image The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) established the Plowshare Program in June 1957 to explore the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. The program took its name from the Bible (Isaiah 2:4), "they will beat their swords into plowshares." The purpose of the AEC program, instituted by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), was to develop the necessary technology for using nuclear explosions for civil and industrial projects, such as the creation of harbors and canals and the stimulation of natural gas reservoirs. Watch the 11 minute film, "Civilian Applications of Nuclear Explosives." The idea of using nuclear explosions for non-military purposes was first raised by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in his famous "Atoms for Peace" speech in December 1953 -- an idea that resonated with Edward Teller. In the summer of 1956, Harold Brown (LLNL director, 1960-1961) proposed a symposium on the subject to the AEC, and a meeting was held at LLNL in February 1957. Some 24 papers were presented, covering a broad array of ideas. While interest was high, discussions were hampered by the lack of data on the effects of underground explosions. Such data was subsequently generated with the Rainier event in September 1957. On Sept. 19, 1957, LLNL conducted the first contained underground nuclear explosion. Rainier was fired beneath a high mesa at the Nevada Test Site. -

Atoms for Peace and War, 1953-1961: Eisenhower and the on the Effects Ofnuclear Weapons, Stating That, "...Personal Atomic Energy Commission

Atoms for Peace and War, 1953-1961: Eisenhower and the on the effects ofnuclear weapons, stating that, "...personal Atomic Energy Commission. (A History of the United ly I think the time has arrived when the American people States Atomic Energy Commission, Vol. 3.) Richard G. must have more information on this subject, if they are to Hewlett and Jack M. Holl. 725 pp. University ofCalifor act intelligently.. .! think the time has come to be far more, nia Press, Berkeley, 1989. Price: $60.00 ISBN 0-520 let us say, frank with the American people than we have 06018-0. (Reviewed by David Hafemeister.) been in the past" (p. 55). By informing the public more about the effects of megaton blasts, but not informing the Ifyou wish to become informed on the present history of public about the danger to uranium miners and the fall-out nuclear arms control negotiations in the 1970s and 80s, at St. George, Utah, the goals of "candor" were only par read Strobe Talbott's trilogy: Endgame, Deadly Gambits, tially fulfilled. By amending the Atomic Energy Act of and Masterofthe Game. Ifyou wish to become informed on 1946, some of the secrets of the atom were unclassified in the in-depth, historical beginnings of the atomic age, read order to establish the commercial fuel cycle. Atoms for Richard Hewlett's trilogy: The New World, 1939-1946, Peace ultimately creates a dilemma. Greater access by oth Atomic Shield, 1947-1952, and the subject of this review, ercountries to nuclear methods and special nuclear materi the recently released AtomsforPeace and War, 1953-1961. -

Plowshare Program

Acknowledgements The U.S. Department of Energy, Nevada Operations Office, Office of Public Affairs and Information, acknowledges the contribution of Dr. William C. Beck, Belfort Engineering & Environmental Services, Incorporated, for providing historical information for this publication; Patricia Nolan Bodin, Janine M. Ford, Sandra A. Smith and Warren S. Udy, U.S. Department of Energy, Nevada Operations Office, Office of Public Affairs and Information; Beverly A. Bull, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; Richard Reed, Remote Sensing Laboratory (operated by Bechtel Nevada); Carole Schoengold, Martha DeMarre, Coordination and Information Center (operated by Bechtel Nevada); Loretta Bush, Technical Information Resource Center (operated by Bechtel Nevada). i Executive Summary Plowshare Program Introduction The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), now the Department of Energy (DOE), established the Plowshare Program as a research and development activity to explore the technical and economic feasibility of using nuclear explosives for industrial applications. The reasoning was that the relatively inexpensive energy available from nuclear explosions could prove useful for a wide variety of peaceful purposes. The Plowshare Program began in 1958 and continued through 1975. Between December 1961 and May 1973, the United States conducted 27 Plowshare nuclear explosive tests comprising 35 individual detonations. Conceptually, industrial applications resulting from the use of nuclear explosives could be divided into two broad categories: 1) large-scale excavation and quarrying, where the energy from the explosion was used to break up and/or move rock; and 2) underground engineering, where the energy released from deeply buried nuclear explosives increased the permeability and porosity of the rock by massive breaking and fracturing. Possible excavation applications included: canals, harbors, highway and railroad cuts through mountains, open pit mining, construction of dams, and other quarry and construction-related projects.