Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start) -

Special Issues

FOR WEEK ENDING JANUARY 20, 1990 Billboard Billboard. Hot Black Singles SALES & AIRPLAYTM A ranking of the top 40 black singles by sales and airplay. respectively, with reference to each title's composite position on the main Hot Black Singles chart. SALES § AIRPLAY m5 TITLE ARTIST g TITLE ARTIST g 1 3 ILL BE GOOD TO YOU QUINCY 1 1 2 JONES I'LL BE GOOD TO YOU QUINCY JONES 1 SPECIAL 4 ISSUES 2 LET'S GET IT ON BY ALL MEANS 3 2 5 MAKE IT LIKE IT WAS REGINA BELLE 2 3 9 MAKE IT LIKE IT WAS REGINA BELLE 2 3 6 SILKY SOUL MAZE FEATURING FRANKIE BEVERLY 4 4 5 PUMP UP THE JAM TECHNOTRONIC FEATURING FELLY 11 4 4 LET'S GET IT ON BY ALL MEANS 3 SPOTLIGHT ISSUE IN THIS SECTION AD DEADLINE 5 1 RHYTHM NATION JANET JACKSON 5 5 10 WALK ON BY SYBIL 8 6 6 SILKY SOUL MAZE FEATURING FRANKIE BEVERLY 4 6 8 I WANNA BE RICH CALLOWAY 10 7 10 REAL LOVE SKYY 6 7 11 REAL LOVE SKYY 6 8 12 ALL NITE 7 7 ENTOUCH FEATURING KEITH SWEAT 8 ALL NITE ENTOUCH FEATURING KEITH SWEAT 7 ART Feb 17 Art At 30 Jan 23 9 14 HOLD ME SERIOUS ON O'JAYS 9 9 1 RHYTHM NATION JANET JACKSON 5 LABOE History 10 13 WALK ON BY SYBIL 8 10 9 SERIOUS HOLD ON ME O'JAYS 9 11 11 TURN IT OUT ROB BASE 17 11 13 SPECIAL THE TEMPTATIONS 14 30TH Oldies 12 2 TENDER LOVER BABYFACE 13 12 15 YOUR SWEETNESS GOOD GIRLS 15 Newies 13 20 f WANNA BE RICH CALLOWAY 10 13 18 SCANDALOUS! PRINCE 12 14 27 SCANDALOUS! PRINCE 12 14 17 NO FRIEND OF MINE CLUB NOUVEAU 16 15 21 NO FRIEND OF MINE CLUB NOUVEAU 16 15 16 SHOULD HAVE BEEN YOU MICHAEL COOPER 21 JOHNNY Feb 24 The Man Jan 30 16 29 40 MORE LIES MICHELLE 18 16 3 TENDER LOVER -

{FREE} the Heart Is a Noisy Room : Your Inner Voices, Why They Matter

THE HEART IS A NOISY ROOM : YOUR INNER VOICES, WHY THEY MATTER - AND HOW TO WIN THEM OVER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dr Ronald Boyd-MacMillan | 208 pages | 22 Jan 2019 | HODDER & STOUGHTON | 9781473677142 | English | London, United Kingdom The Heart is a Noisy Room : Your inner voices, why they matter - and how to win them over PDF Book In , he went to Croatia to write about the war that was then engulfing the Balkans. The answer is simple: none of them. But God has another standard. Are you reporting for duty? Calling all HuffPost superfans! Your heart voice, on the other hand, lives in an environment of stillness, tranquillity, calm, peacefulness and triggers your PNS, parasympathetic nervous system. By signing up you are agreeing to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. I can feel it too much. This is where your blog key for this blog comes in. Until such a voice is named, we cannot find ways to keep the voice in a proper place — doubt and questioning have a valuable place, but not as the only response to life. Book recommendations:. This is not the typical stuff of oratory meets, where even speeches about the most hot-button topics are studiously mild. Get out of the way. Bristol Cathedral is entering a new season following the arrival of a new Dean in October For now, understand it is this voice we need to learn to commune with as we continue to understand ourselves at a deeper level. Contributors control their own work and posted freely to our site. -

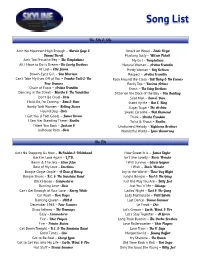

Skyline Orchestras

PRESENTS… SKYLINE Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, you’ll be viewing the band Skyline, led by Ross Kash. Skyline has been performing successfully in the wedding industry for over 10 years. Their experience and professionalism will ensure a great party and a memorable occasion for you and your guests. In addition to the music you’ll be hearing tonight, we’ve supplied a song playlist for your convenience. The list is just a part of what the band has done at prior affairs. If you don’t see your favorite songs listed, please ask. Every concern and detail for your musical tastes will be held in the highest regard. Please inquire regarding the many options available. Skyline Members: • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES…………………………..…….…ROSS KASH • VOCALS……..……………………….……………………………….….BRIDGET SCHLEIER • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..………….…………………….……VINCENT FONTANETTA • GUITAR………………………………….………………………………..…….JOHN HERRITT • SAXOPHONE AND FLUTE……………………..…………..………………DAN GIACOMINI • DRUMS, PERCUSSION AND VOCALS……………………………….…JOEY ANDERSON • BASS GUITAR, VOCALS AND UKULELE………………….……….………TOM MCGUIRE • TRUMPET…….………………………………………………………LEE SCHAARSCHMIDT • TROMBONE……………………………………………………………………..TIM CASSERA • ALTO SAX AND CLARINET………………………………………..ANTHONY POMPPNION www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 DANCE: 24K — BRUNO MARS A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY — FERGIE A SKY FULL OF STARS — COLD PLAY LONELY BOY — BLACK KEYS AIN’T IT FUN — PARAMORE LOVE AND MEMORIES — O.A.R. ALL ABOUT THAT BASS — MEGHAN TRAINOR LOVE ON TOP — BEYONCE BAD ROMANCE — LADY GAGA MANGO TREE — ZAC BROWN BAND BANG BANG — JESSIE J, ARIANA GRANDE & NIKKI MARRY YOU — BRUNO MARS MINAJ MOVES LIKE JAGGER — MAROON 5 BE MY FOREVER — CHRISTINA PERRI FT. ED SHEERAN MR. SAXOBEAT — ALEXANDRA STAN BEST DAY OF MY LIFE — AMERICAN AUTHORS NO EXCUSES — MEGHAN TRAINOR BETTER PLACE — RACHEL PLATTEN NOTHING HOLDING ME BACK — SHAWN MENDES BLOW — KE$HA ON THE FLOOR — J. -

Most Requested Songs of 2009

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on nearly 2 million requests made at weddings & parties through the DJ Intelligence music request system in 2009 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 4 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 5 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 6 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 7 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 8 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 9 B-52's Love Shack 10 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 11 ABBA Dancing Queen 12 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 13 Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow 14 Rihanna Don't Stop The Music 15 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 16 Outkast Hey Ya! 17 Sister Sledge We Are Family 18 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 19 Kool & The Gang Celebration 20 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 21 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 22 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 23 Lady Gaga Poker Face 24 Beatles Twist And Shout 25 James, Etta At Last 26 Black Eyed Peas Let's Get It Started 27 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 28 Jackson, Michael Thriller 29 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 30 Mraz, Jason I'm Yours 31 Commodores Brick House 32 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 33 Temptations My Girl 34 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 35 Vanilla Ice Ice Ice Baby 36 Bee Gees Stayin' Alive 37 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 38 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

Daryl Lowery Sample Songlist Bridal Songs

DARYL LOWERY SAMPLE SONGLIST BRIDAL SONGS Song Title Artist/Group Always And Forever Heatwave All My Life K-Ci & Jo JO Amazed Lonestar At Last Etta James Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Breathe Faith Hill Can't Help Falling In Love Elvis Presley Come Away With Me Nora Jones Could I Have This Dance Anne Murray Endless Love Lionel Ritchie & Diana Ross (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams From This Moment On Shania Twain & Brian White Have I Told You Lately Rod Stewart Here And Now Luther Van Dross Here, There And Everywhere Beatles I Could Not Ask For More Edwin McCain I Cross My Heart George Strait I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees I Don't Want To Miss A Thing Aerosmith I Knew I Loved You Savage Garden I'll Always Love You Taylor Dane In Your Eyes Peter Gabriel Just The Way You Are Billy Joel Keeper Of The Stars Tracy Byrd Making Memories Of Us Keith Urban More Than Words Extreme One Wish Ray J Open Arms Journey Ribbon In The Sky Stevie Wonder Someone Like You Van Morrison Thank You Dido That's Amore Dean Martin The Way You Look Tonight Frank Sinatra The Wind Beneath My Wings Bette Midler Unchained Melody Righteous Brothers What A Wonderful World Louis Armstrong When A Man Loves A Woman Percy Sledge Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton You And Me Lifehouse You're The Inspiration Chicago Your Song Elton John MOTHER/SON DANCE Song Title Artist/Group A Song For Mama Boyz II Men A Song For My Son Mikki Viereck You Raise Me Up Josh Groban Wind Beneath My Wings Bette Midler FATHER/DAUGHTER DANCE Song Title Artist/Group Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Butterfly Kisses Bob Carlisle Daddy's Little Girl Mills Brothers Unforgettable Nat & Natalie King Cole What A Wonderful World Louis Armstrong Popular Selections: "Big Band” To "Hip Hop" Song Title Artist/Group (Oh What A Night) December 1963 Four Seasons 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 21 Questions 50 Cent 867-5309 Tommy Tutone A New Day Has Come Celine Dion A Song For My Son Mikki Viereck A Thousand Years Christine Perri A Wink And A Smile Harry Connick, Jr. -

Broadside Songbook

a d..sid..e BOB DYLAN: W"HAT HIS SONGS REALLY SAY ; DIANA DAVIES IN THIS ISSUE: Bob Dylan's songs interpreted by Alan Weberman, who finds in them the radical militant continuing to protest The Establishment. ALSO: Songs by ARLO GUTHRIE, BRUCE PHILLIPS, PABLO NERUDA, JAN DAVIDSON. FOREWORD Dear Readers of this Songbook: I got a check in the mail the other day. It Bill." They spelled out in detail the whole was for $3,050.06. It came, like similar list of a nation's crime against a people - ones before it over the last few years, by with a clear and precise schedule of cash pay airmail from a Berlin bank in Germany. As ments due. for each. All realistically worked usual, the explanation on the check said in out in negotiations with the Germans. A cash German, ENTSCHADIGUNGSZAHLUNG. I still can't value placed on all the categories of horrors! pronounce it, but I can translate it: RESTI So much for Loss of Life ... Loss of Liberty •.. TUTION PAYMENT. Restitution! To whom? For Loss of Health ... of Parents ... of Education .. c.what? Most important of all -- ~ whom? of Property ... bf Inheritance ... of Insurance .. stitution to the survivors and victims of of Business. It was an enormous task, cover ial persecution for the deaths and terrible ing 13 years, and the accounting involved ses they suffered under the Nazi government some six million people killed by the Nazis. Germany. Paid out -- not by the actually But the restitution payments have made it ty Hitler government, but by the suc- possible for the surviving vict~ms of 7ac~sm or government which accepted its responsi to start a decent life over aga1n. -

The BG News September 3, 1997

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 9-3-1997 The BG News September 3, 1997 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News September 3, 1997" (1997). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6196. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6196 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. TODAY Directory SPORTS OPINION 2 Switchboard 372-2601 Classified Ads 372-6977 Natalie: Beware of first impressions Display Ads 372-2605 Women's Soccer Editorial 372-6966 Sports 372-2602 at Dayton cool Entertainment 372-2603 tonight, 7:30 p.m. WORLD 5 *# Story Idea? Give us a call Falcons search for second victory of the and sunny weekdays from I pm. to 5 pm., or season on the road against Flyers Russians trying to blame Mir's team j$f e-mail: "[email protected]" High: 68 Low: 51 WEDNESDAY September 3,1997 Volume 84, Issue 5 The BG News Bowling Green, Ohio n "Serving the Bowling Green community for over 75years" Suspects faced with manslaughter Paparazzi placed under formal investigation The Associated Press PARIS - A French judge de- clared seven paparazzi to be manslaughter suspects Tuesday in the death of Princess Diana, including one aggressive photog- rapher said to have felt the dying princess's pulse while snapping shots of the car wreck. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

90'S-2000'S Ballads 1. with Open Arms

90’s-2000’s Ballads 14. Fooled Around And Fell In Love - Elvin Bishop 1. With Open Arms - Creed 15. I Just Wanna Stop - Gino Vannelli 2. Truly Madly Deeply - Savage Garden 16. We've Only Just Begun - The Carpenters 3. I Knew I Loved You - Savage Garden 17. Easy - Commodores 4. As Long As You Love Me - Backstreet Boys 18. Three Times A Lady - Commodores 5. Last Kiss - Pearl Jam 19. Best Of My Love - Eagles 6. Aerosmith - Don't Wanna Miss A Thing 20. Lyin' Eyes - Eagles 7. God Must Have Spent A Little More Time - N'Sync 21. Oh Girl - The Chi-Lites 8. Everything I Do - Bryan Adams 22. That's The Way Of The World - Earth Wind & Fire 9. Have I Told You Lately - Rod Stewart 23. The Wedding Song - Paul Stokey 10. When A Man Loves A Woman - Michael Bolton 24. Wonder Of You - Elvis Presley 11. Oh Girl - Paul Young 25. You Are The Sunshine Of My Life - Stevie Wonder 12. Love Will Keep Us Alive - Eagles 26. You've Got A Friend - James Taylor 13. Can You Feel The Love Tonight - Elton John 27. Annie's Song - John Denver 14. I Can't Fight This Feeling Anymore - R.E.O. 28. Free Bird - Lynyrd Skynyrd 15. Unforgettable - Natalie Cole 29. Riders On The Storm - Doors 16. Endless Love - Luther Vandross 30. Make It With You - Bread 17. Forever In Love - Kenny G 31. If - Bread 18. Butterfly Kisses - Bob Carlisle 32. Fallin' In Love - Hamilton, Joe Frank & Reynolds 19. Unforgettable - Nat King & Natalie Cole 33. -

New Song List.Pages

Song List Te 50s & 60s Ain’t No Mountain High Enough – Marvin Gaye & Knock on Wood – Eddie Floyd Tammi Terrell Mustang Sally – Wilson Pickett Ain’t Too Proud to Beg – Te Temptations My Girl – Temptations All I Have to Do Is Dream - Te Everly Brothers Natural Woman – Aretha Franklin At Last – Etta Jame Pretty Woman – Roy Orbion Brown-Eyed Girl – Van Morrion Respect – Aretha Franklin Can’t Take My Eyes Off of You – Frankie Valli & Te Rock Around the Clock - Bill Haley & Hi Comets Four Seaons Rocky Top – Various Artits Chain of Fools – Aretha Franklin Shout – Te Isley Brothers Dancing in the Street – Martha & Te Vandella Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay – Oti Redding Don’t Be Cruel - Elvi Soul Man – Sam & Dave Hold On, I’m Coming – Sam & Dave Stand by Me – Ben E. King Honky Tonk Women – Rolling Stone Sugar, Sugar - Te Archie Hound Dog - Elvi Sweet Caroline – Neil Diamond I Got You (I Feel Good) – Jame Brown Think – Aretha Franklin I Saw Her Standing There - Beatle Twist & Shout – Beatle I Want You Back – Jackson 5 Unchained Melody – Righteous Brothers Jailhouse Rock - Elvi Wonderful World – Loui Armstrong Te 70s Ain’t No Stopping Us Now – McFadden & Whitehead How Sweet It Is – Jame Taylor Back in Love Again – L.T.D. Isn’t She Lovely – Stevie Wonder Benni & The Jets – Elton John I Will Survive – Gloria Gaynor Best of My Love – Emotions I Wish – Stevie Wonder Boogie Oogie Oogie – A Tate of Honey Joy to the World – Tree Dog Night Boogie Shoes – K.C. & Te Sunshine Band Jungle Boogie – Kool & Te Gang Brick House – Commodore Just the Way You Are – Billy Joel Burning Love - Elvi Just You ‘n’ Me – Chicago Can’t Get Enough of Your Love – Barry White Ladies’ Night – Kool & Te Gang Car Wash – Roe Royce Lady Marmalade – Patti Labelle Dancing Queen – ABBA Last Dance - Donna Summer December 1963 – Four Seaons Le Freak – Chic Disco Inferno – Te Trammps Let’s Groove – Earth, Wind, & Fire Easy – Commodore Let’s Stay Together – Al Green Fire – Ohio Players Long Train Runnin’ – Te Doobie Brothers Fire – Pointer Siters Love Rollercoaster – Ohio Players Get Down Tonight – K.C. -

Sizzling 70'S Printable List

Sizzling 70’s Printable List SHE'S IN LOVE WITH YOU SUZI QUATRO BEST OF MY LOVE EAGLES WHERE YOU LEAD BARBARA STREISAND SAY YOU LOVE ME FLEETWOOD MAC SHINING STAR EARTH WIND & FIRE MIND GAMES JOHN LENNON LOVE'S THEME LOVE UNLIMITED GIRLS ON THE AVENUE RICHARD CLAPTON SOFT DELIGHTS NEW DREAM CRACKLIN' ROSIE NEIL DIAMOND AIN'T GONNA BUMP NO MORE (WITH NO BIG FAT WOMAN) JOE TEX BECAUSE I LOVE YOU MASTER'S APPRENTICES RIDE A WHITE SWAN T REX PRECIOUS LOVE BOB WELCH PRELUDE/ANGRY YOUNG MAN BILLY JOEL STAYIN' ALIVE BEE GEES EVERYBODY PLAYS THE FOOL MAIN INGREDIENT ROCK AND ROLL ALL NITE KISS NA NA HEY HEY KISS HIM GOODBYE STEAM GOODBYE STRANGER SUPERTRAMP NEVER CAN SAY GOODBYE GLORIA GAYNOR GOODBYE TO LOVE CARPENTERS BABY IT'S YOU PROMISES (YOU GOTTA WALK) DON'T LOOK BACK PETER TOSH SATURDAY NIGHT BAY CITY ROLLERS SATURDAY NIGHTS ALRIGHT FOR FIGHTING ELTON JOHN ANOTHER SATURDAY NIGHT CAT STEVENS DANCIN' (ON A SATURDAY NIGHT) BARRY BLUE TUMBLING DICE ROLLING STONES SHAKE YOUR BOOTY K.C. & SUNSHINE BAND COZ I LUV YOU SLADE BANKS OF THE OHIO OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN MORE THAN A FEELING BOSTON FEELING ALRIGHT JOE COCKER GOOD FEELIN MAX MERRITT PEACEFUL EASY FEELING EAGLES HELLO ITS ME TODD RUNDGREN EBONY EYES BOB WELCH STAR SONG MARTY RHONE EGO (IS NOT A DIRTY WORD) SKYHOOKS ON THE COVER OF THE ROLLING STONE DR HOOK I HEAR YOU KNOCKING DAVE EDMUNDS EVERLASTING LOVE ANDY GIBB LET'S PRETEND RASPBERRIES WHO'LL STOP THE RAIN CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL BICYCLE RACE QUEEN YOU TOOK THE WORDS RIGHT OUT OF MY MOUTH (HOT SU MEAT LOAF CAPTAIN ZERO MIXTURES SWEET