Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

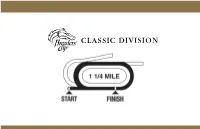

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

World Thoroughbred Racehorse Rankings Conference

EUROPEAN THOROUGHBRED RACEHORSE RANKINGS — 2006 TWO-YEAR-OLDS ICR Kg Age Sex Pedigree Owner Trainer Trained Name 123 55.5 Teofilo (IRE) 2 C Galileo (IRE)--Speirbhean (IRE) Mrs J. S. Bolger J. S. Bolger IRE 122 55.5 Holy Roman Emperor (IRE) 2 C Danehill (USA)--L'On Vite (USA) Mrs John Magnier A. P. O'Brien IRE 121 55 Dutch Art (GB) 2 C Medicean (GB)--Halland Park Lass (IRE) Mrs Susan Roy P. W. Chapple-Hyam GB 119 54 Finsceal Beo (IRE) 2 F Mr Greeley (USA)--Musical Treat (IRE) M. A. Ryan J. S. Bolger IRE Mount Nelson (GB) 2 C Rock of Gibraltar (IRE)--Independence (GB) Mr D. Smith, Mrs J. Magnier, Mr M. Tabor A. P. O'Brien IRE 118 53.5 Spirit One (FR) 2 C Anabaa Blue (GB)--Lavayssiere (FR) B. Chehboub P. H. Demercastel FR 117 53 Battle Paint (USA) 2 C Tale of The Cat (USA)--Black Speck (USA) J. Allen Jean Claude Rouget FR Strategic Prince (GB) 2 C Dansili (GB)--Ausherra (USA) H.R.H. Sultan Ahmad Shah P. F. I. Cole GB 116 52.5 Authorized (IRE) 2 C Montjeu (IRE)--Funsie (FR) Saleh Al Homaizi & Imad Al Sagar P. W. Chapple-Hyam GB Captain Marvelous (IRE) 2 C Invincible Spirit (IRE)--Shesasmartlady (IRE) Mr R. J. Arculli B. W. Hills GB Eagle Mountain (GB) 2 C Rock of Gibraltar (IRE)--Masskana (IRE) Mr D. Smith, Mrs J. Magnier, Mr M. Tabor A. P. O'Brien IRE Haatef (USA) 2 C Danzig (USA)--Sayedat Alhadh (USA) Mr Hamdan Al Maktoum K. -

Betty Parsons Heated Sky Alexander Gray Associates Gray Alexander Betty Parsons: Heated Sky February 26 – April 4, 2020

Betty Parsons Sky Heated Betty Parsons: Heated Sky Alexander Gray Associates Betty Parsons: Heated Sky February 26 – April 4, 2020 Alexander Gray Associates Betty Parsons in her Southold, Long Island, NY studio, Spring 1980 2 3 Betty Parsons in her Southold, Long Island, NY studio, 1971 5 Introduction By Rachel Vorsanger Collection and Research Manager Betty Parsons and William P. Rayner Foundation Betty Parsons’ boundless energy manifested itself not only in her various forms of artistic expression—paintings of all sizes, travel journals, and her eponymous gallery— but in her generosity of spirit. Nearly four decades after Parsons’ death, her family, friends, and former colleagues reinforce this character trait in conversations and interviews I have conducted, in order to better understand the spirit behind her vibrant and impassioned works. Betty, as I have been told was her preferred way to be addressed, was a woman of many actions despite her reticent nature. She took younger family members under her wing, introducing them to major players in New York’s mid-century art world and showing them the merits of a career in the arts. As a colleague and mentor, she encouraged the artistic practice of gallery assistants and interns. As a friend, she was a constant source of inspiration, often appearing as the subject of portraits and photographs. Perhaps her most deliberate act of generosity was the one that would extend beyond her lifetime. As part of her will, she established the Betty Parsons Foundation in order to support emerging artists from all backgrounds, and to support ocean life. After her nephew Billy Rayner’s death in 2018, the Foundation was further bolstered to advance her mission. -

Media Guide 2020

MEDIA GUIDE 2020 Contents Welcome 05 Minstrel Stakes (Group 2) 54 2020 Fixtures 06 Jebel Ali Racecourse & Stables Anglesey Stakes (Group 3) 56 Race Closing 2020 08 Kilboy Estate Stakes (Group 2) 58 Curragh Records 13 Sapphire Stakes (Group 2) 60 Feature Races 15 Keeneland Phoenix Stakes (Group 1) 62 TRM Equine Nutrition Gladness Stakes (Group 3) 16 Rathasker Stud Phoenix Sprint Stakes (Group 3) 64 TRM Equine Nutrition Alleged Stakes (Group 3) 18 Comer Group International Irish St Leger Trial Stakes (Group 3) 66 Coolmore Camelot Irish EBF Mooresbridge Stakes (Group 2) 20 Royal Whip Stakes (Group 3) 68 Coolmore Mastercraftsman Irish EBF Athasi Stakes (Group 3) 22 Coolmore Galileo Irish EBF Futurity Stakes (Group 2) 70 FBD Hotels and Resorts Marble Hill Stakes (Group 3) 24 A R M Holding Debutante Stakes (Group 2) 72 Tattersalls Irish 2000 Guineas (Group 1) 26 Snow Fairy Fillies' Stakes (Group 3) 74 Weatherbys Ireland Greenlands Stakes (Group 2) 28 Kilcarn Stud Flame Of Tara EBF Stakes (Group 3) 76 Lanwades Stud Stakes (Group 2) 30 Round Tower Stakes (Group 3) 78 Tattersalls Ireland Irish 1000 Guineas (Group 1) 32 Comer Group International Irish St Leger (Group 1) 80 Tattersalls Gold Cup (Group 1) 34 Goffs Vincent O’Brien National Stakes (Group 1) 82 Gallinule Stakes (Group 3) 36 Moyglare Stud Stakes (Group 1) 84 Ballyogan Stakes (Group 3) 38 Derrinstown Stud Flying Five Stakes (Group 1) 86 Dubai Duty Free Irish Derby (Group 1) 40 Moyglare ‘Jewels’ Blandford Stakes (Group 2) 88 Comer Group International Curragh Cup (Group 2) 42 Loughbrown -

138904 03 Dirtmile.Pdf

breeders’ cup dirt mile BREEDERs’ Cup DIRT MILE (GR. I) 7th Running Santa Anita Park $1,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS AND UPWARD ONE MILE Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 123 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 120 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $1 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Dirt Mile will be limited to twelve (12). If more than twelve (12) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge Winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Friday, November 1, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Dirt Mile (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Alpha Godolphin Racing, LLC Lessee Kiaran P. McLaughlin B.c.4 Bernardini - Munnaya by Nijinsky II - Bred in Kentucky by Darley Broadway Empire Randy Howg, Bob Butz, Fouad El Kardy & Rick Running Rabbit Robertino Diodoro B.g.3 Empire Maker - Broadway Hoofer by Belong to Me - Bred in Kentucky by Mercedes Stables LLC Brujo de Olleros (BRZ) Team Valor International & Richard Santulli Richard C. -

SYLVIA SLEIGH Born 1916, Wales Deceased 2010, New York City

SYLVIA SLEIGH Born 1916, Wales Deceased 2010, New York City Education Depuis 1788 Brighton School of Art, Sussex, England Freymond-Guth Fine Arts Riehenstrasse 90 B CH 4058 Basel T +41 (0)61 501 9020 offi[email protected] www.freymondguth.com Selected Exhibitions & Projects („s“ = Solo Exhibition) 2017 Whitney Museum for American Art, New York, USA Mostyn, Llundadno, Wales, UK (s) Reflections on the surface, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Basel, CH 2016 MUMOK Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Vienna, AUT Museum Brandhorst, Munich, DE 2015 The Crystal Palace, Sylvia Sleigh I Yorgos Sapountzis, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Sadie Coles HQ, London, UK 2014 Shit and Die, Palazzo Cavour, cur. Maurizio Cattelan, Turin, IT Praxis, Wayne State University‘s Elaine L. Jacob Gallery, Detroit, USA Frieze New York, with Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, New York, NY Le salon particulier, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH (s) 2013 / 14 Sylvia Sleigh, CAPC Musée d‘Art Contemporain de Bordeaux Bordeaux, FR (s) Tate Liverpool, UK, (s) CAC Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporanea Sevilla, ES (s) 2013 The Weak Sex / Das schwache Geschlecht, Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern, CH 2012 Sylvia Sleigh, cur. Mats Stjernstedt, Giovanni Carmine, Alexis Vaillant in collaboration w Francesco Manacorda and Katya Garcia-Anton, Kunstnernes Hus Oslo, NOR (s) Kunst Halle St. Gallen, CH (s) Physical! Physical!, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH 2011 Art 42 Basel: Art Feature (with Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich), Basel CH (s) The Secret Garden, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Anyone can do anything? genius without talents, cur. Ann Demeester, De Appel, Amsterdam, NL 2010 Working at home, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH (s) The Comfort of Strangers, curated by Cecila Alemani, PS1 Contemporary Art Cen ter, New York, NY 2009 I-20 Gallery, New York, NY (s) Wiser Than God, curated by Adrian Dannatt, BLT Gallery, New York, NY The Three Fs: form, fashion, fate, curated by Megan Sullivan, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Ingres and the Moderns, Musée national des Beaux-Arts, Quebec. -

LAWRENCE ALLOWAY Pedagogy, Practice, and the Recognition of Audience, 1948-1959

LAWRENCE ALLOWAY Pedagogy, Practice, and the Recognition of Audience, 1948-1959 In the annals of art history, and within canonical accounts of the Independent Group (IG), Lawrence Alloway's importance as a writer and art critic is generally attributed to two achievements: his role in identifying the emergence of pop art and his conceptualization of and advocacy for cultural pluralism under the banner of a "popular-art-fine-art continuum:' While the phrase "cultural continuum" first appeared in print in 1955 in an article by Alloway's close friend and collaborator the artist John McHale, Alloway himself had introduced it the year before during a lecture called "The Human Image" in one of the IG's sessions titled ''.Aesthetic Problems of Contemporary Art:' 1 Using Francis Bacon's synthesis of imagery from both fine art and pop art (by which Alloway meant popular culture) sources as evidence that a "fine art-popular art continuum now eXists;' Alloway continued to develop and refine his thinking about the nature and condition of this continuum in three subsequent teXts: "The Arts and the Mass Media" (1958), "The Long Front of Culture" (1959), and "Notes on Abstract Art and the Mass Media" (1960). In 1957, in a professionally early and strikingly confident account of his own aesthetic interests and motivations, Alloway highlighted two particular factors that led to the overlapping of his "consumption of popular art (industrialized, mass produced)" with his "consumption of fine art (unique, luXurious):' 3 First, for people of his generation who grew up interested in the visual arts, popular forms of mass media (newspapers, magazines, cinema, television) were part of everyday living rather than something eXceptional. -

India Progressive Writers Association; *7:Arxicm

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 124 936 CS 202 742 ccpp-.1a, CsIrlo. Ed. Marxist Influences and South Asaan li-oerazure.South ;:sia Series OcasioLal raper No. 23,Vol. I. Michijar East Lansing. As:,an Studies Center. PUB rAIE -74 NCIE 414. 7ESF ME-$C.8' HC-$11.37 Pius ?cstage. 22SCrIP:0:", *Asian Stud,es; 3engali; *Conference reports; ,,Fiction; Hindi; *Literary Analysis;Literary Genres; = L_tera-y Tnfluences;*Literature; Poetry; Feal,_sm; *Socialism; Urlu All India Progressive Writers Association; *7:arxicm 'ALZT:AL: Ti.'__ locument prasen-ls papers sealing *viithvarious aspects of !',arxi=it 2--= racyinfluence, and more specifically socialisr al sr, ir inlia, Pakistan, "nd Bangladesh.'Included are articles that deal with _Aich subjects a:.the All-India Progressive Associa-lion, creative writers in Urdu,Bengali poets today Inclian poetry iT and socialist realism, socialist real.Lsm anu the Inlion nov-,-1 in English, the novelistMulk raj Anand, the poet Jhaverchan'l Meyhani, aspects of the socialistrealist verse of Sandaram and mash:: }tar Yoshi, *socialistrealism and Hindi novels, socialist realism i: modern pos=y, Mohan Bakesh andsocialist realism, lashpol from tealist to hcmanisc. (72) y..1,**,,A4-1.--*****=*,,,,k**-.4-**--4.*x..******************.=%.****** acg.u.re:1 by 7..-IC include many informalunpublished :Dt ,Ivillable from othr source r.LrIC make::3-4(.--._y effort 'c obtain 1,( ,t c-;;,y ava:lable.fev,?r-rfeless, items of marginal * are oft =.ncolntered and this affects the quality * * -n- a%I rt-irodu::tior:; i:";IC makes availahl 1: not quali-y o: th< original document.reproductiour, ba, made from the original. -

Deadline to Nominate

The World's SATURDAY, 29TH MAY 2021 Yearling Sale EBN EUROPEAN BLOODSTOCK NEWS SEPTEMBERMON. 13 - SAT. 25 FOR MORE INFORMATION: TEL: +44 (0) 1638 666512 • [email protected] • WWW.BLOODSTOCKNEWS.EU • L@bloodstocknews TODAY’S HEADLINES ARQANA EBN Sales Talk Click here to is brought to contact IRT, or you by IRT visit www.irt.com STRONG DEMAND KEY AT ARQANA BREEZE-UP For the second year running, the transplanted Arqana Breeze-Up Sale shrugged off the difficulties of a cross-Channel move and a delay to prove a hit in Doncaster, with strong demand throughout and an international cast of buyers securing choice lots, writes Amy Bennett. Lot 90, a colt by Medaglia D’Oro consigned by Malcolm Trade was headed by a son of Medaglia D’Oro who outstripped Bastard, topped the Arqana Breeze-Up Sale, held at Goffs UK last year’s top price of £650,000 when the hammer eventually in Doncaster yesterday, when being purchased by Godolphin came down at £675,000. for £675,000. © Steve Davies The spirited bidding battle went the way of Anthony Stroud, who confirmed: “He’s been bought for Godolphin. He did a very nice breeze and Malcolm Bastard does a fantastic job, he’s very good at bringing these horses on. He was the horse that we wanted.” The colt’s delighted consignor added: “He is a fantastic horse, he IN TODAY’S ISSUE... breezed great and he has a superb temperament. There is a lot of improvement to come from him. Leading sires’ table p7 “I don’t got excited, I’m realistic, but it’s turning out to be a good Stallion news p8 sale. -

Inside an Unquiet Mind Essays on the Critic and Curator Lawrence Alloway Give a Minor Figure Too Much Credit by Pac Pobric | 19 June 2015 | the Art Newspaper

Inside an unquiet mind Essays on the critic and curator Lawrence Alloway give a minor figure too much credit by Pac Pobric | 19 June 2015 | The Art Newspaper Lawrence Alloway, then a curator at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, speaks at Oberlin College, Ohio, in 1965. Courtesy: Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Of all the minor figures in the history of art criticism, perhaps none is as deserving of his footnote in the annals as the British writer and curator Lawrence Alloway (1926-90). Although he is best known for supposedly coining the term “Pop art” (in fact, no one knows where the phrase originated), Alloway is more important for the small role he played in ushering in the criticism that plagues us today: the type so obsessed with the noise of the art world that it forgets the work entirely. In Alloway’s mind, works of art were “historical documents”, as he put it in 1964— relics, that is, to be unearthed and decoded by the critic as anthropologist. As the art historian Jennifer Mundy explains in an essay in Lawrence Alloway: Critic and Curator, which looks at his work in comprehensive detail, he called for “a criticism that provided objective descriptions of works and forensic analyses of cultural contexts”. For Alloway, art was an indicator of a system. Beyond that, it was irrelevant. Today, it is Alloway who is irrelevant, and the nine art historians who have contributed to this book (edited by Lucy Bradnock, Courtney Martin and Rebecca Peabody) are far too generous to a man whose ideas were largely stillborn. -

HEADLINE NEWS • 9/25/05 • PAGE 2 of 10

SILVERFOOT IMPRESSES AT HEADLINE KY. DOWNS... p4 NEWS For information about TDN, DELIVERED EACH NIGHT BY FAX AND FREE BY E-MAIL TO SUBSCRIBERS OF call 732-747-8060. www.thoroughbreddailynews.com SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 2005 STAR-STUDDED MILE CROWN FITS NANNINA They may have surrendered the Ashes to England, When it came down to bare knuckles, it was but the Australians were back in the number one spot Cheveley Park Stud’s Nannina (GB) (Medicean {GB}) after Starcraft (NZ) (Soviet Star) had bested Dubawi who pulled the killer punch to oust Alexandrova (Ire) (Ire) (Dubai Millennium {GB}) by 3/4 of a length in yes- (Sadler’s Wells) in yester- terday’s G1 Queen Elizabeth II day’s G1 Fillies' Mile at S. at Newmarket. Last year’s Newmarket. Sent off at 5-1, G1 Australian Derby hero had the Aug. 28 G3 Prestige S. this contest set up for him by winner was temporarily stuck Godolphin’s rabbit Blatant in behind as that rival rolled (GB) (Machiavellian) and had to the front approaching the already done the damage by eighth peg, but her rally took the time that operation’s first Nannina (4) tops Alexandrova her past in the final 100 Starcraft (red) bests Dubawi Getty Images Getty Images string appeared on the scene. yards and she held on for the Answering Christophe-Patrice short-head verdict. “It was a real test and she’s a very Lemaire’s call up the rising ground, the 7-2 shot pulled game filly and gritted her teeth,” commented trainer away to provide owner Paul Makin with the dream John Gosden, celebrating his third success in this con- scenario. -

Dubai Duty Free Shergar Cup

DUBAI DUTY FREE SHERGAR CUP Ascot, Saturday, August 11, 2012 MEDIA GUIDE INDEX 3 THE DUBAI DUTY FREE SHERGAR CUP 4 ORDER OF RUNNING & ADMISSION DETAILS 5 TIMETABLE OF EVENTS, FAMILY ENTERTAINMENT 6 POST-RACING CONCERT – “HERE AND NOW” THE VERY BEST OF THE 1980’s 7 THE PRIZES 8 “BEST DAY’S RACING FOR OWNERS”, DETAILS OF RESERVES, LADBROKES – OFFICAL BOOKMAKER 9 DUBAI DUTY FREE SHERGAR CUP RULES DUBAI DUTY FREE SHERGAR CUP 'DRAW' PROCEDURE & ALLOCATION OF MOUNTS 10 – 13 PROFILES OF PARTICIPATING JOCKEYS 14 PAST WINNERS OF THE “SILVER SADDLE” FOR LEADING JOCKEY AT THE DUBAI DUTY FREE SHERGAR CUP 15 REMEMBERING SHERGAR 16 ABOUT DUBAI DUTY FREE – SPONSORSHIP SUCCESS AS SALES SOAR 17 – 36 PAST RESULTS AT THE DUBAI DUTY FREE SHERGAR CUP 37 KEY ASCOT CONTACTS, ACCREDITATION & MEDIA SERVICES 2 THE DUBAI DUTY FREE SHERGAR CUP • The Dubai Duty Free Shergar Cup is Britain's premier jockeys' competition, a unique event where top jockeys in four teams - Great Britain and Ireland, Europe, the Rest of the World and for the first time this year The Girls - battle against each other in a thrilling six- race showdown. • The six races are limited to 10 runners with either two or three horses racing for each team (this will balance itself out over the course of the afternoon), and points are awarded on a 15, 10, 7, 5, 3 basis to the first five horses home (non runners score 4 points). Subject to full fields, each jockey has five rides and the team with the highest total after the sixth race lifts the Dubai Duty Free Shergar Cup.