Non-Representational Theory and the Creative Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creativity and Place – Conference Timetable

Creativity and Place – conference timetable Wednesday 23rd June Registration from 2pm Welcome David Harvey, Nicola Thomas, Harriet Hawkins 3.00-3.30pm 3.30- 5.00 pm Session 1: A Site and memory Dr Sarah Bennett, University of Plymouth Dis-placing memory: the wall as memory archive Veronica Vickery, University College Falmouth Peopled Places: residual traces of memory and dwelling, material objects and the social Polly Macpherson and Simon Persighetti, University of Plymouth and Dartington College of Arts Reading the Backs B Policy and Place Carmel Confrey, University of West of England Creativity and Place: The Rural Case of Stroud District Gloucestershire Felicity Paynter, Queen Mary, University of London Cultural Values on the edge of the city: cultural policy and development in suburban places David C. Harvey; Nicola J. Thomas and Harriet Hawkins, University of Exeter, Island Creativity, Policy and practice. 5.30-6.30 pm Prof. Sam Smiles (Art History, Plymouth) Key note 6.30-8.00 pm Conference reception Exhibition opening Thursday 24th June 9.00 - 10.30 Session 2: A Creative industries, neighbourhoods and cities Cristina Fregni and Claudia Meschiari From Industrial to Creative, a neighbourhood in Modena Italy Soraia Pereira da Silva Cinematographic Industry in Lisbon: reflexive development and network analysis Sam Henderson (TBC) B Engaging with site: relationality and ethics David Crouch, University of Derby Flirting with space Andrew Stooke, The Oliver Holt Gallery, Sherborne School Places in audience Richard Povall, Aune Head Arts and University College Falmouth, An engaged ethics? Models for engaged practice in the work of Aune Head arts. 10.30- 11.00 Coffee 11.00-12.30 Session 3: A Creative geographies Vladimir Geroimenko, School of Art and Media, University of Plymouth “Plymouth Hoe and the Rest of the World” : The Idea and Production of a Panoramic Digital Painting. -

HARRIET HAWKINS Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University Llandinam Building, Aberystwyth, SY23 3DB, Wales, UK

HARRIET HAWKINS Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University Llandinam Building, Aberystwyth, SY23 3DB, Wales, UK Email: [email protected] PRIMARY RESEARCH AREAS Geography, Art and Aesthetics Geographical thought and methods Creative Industries Esp. themes of embodiment, Esp. the place of Creative Geographies Esp. Cultural perspectives matter, and landscape EDUCATION 10/2002-06/2007 PhD in Geography: Geographies of Rubbish and Art. AHRC funded studentship, School of Geography University of Nottingham 2001-2002 MA Landscape and Culture, AHRC funded studentship, School of Geography University of Nottingham 1998-2001 BA Hons (Geography) Class 1, Awarded the University Prize, the School of Geography Prize and the Edwards Prize School of Geography University of Nottingham RESEARCH AND TEACHING POSITIONS January 2011- NSF/AHRC Research Fellow, Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University. ‘Art-Science Collaborations: bodies and environments.’ September 2010- Lecturer in Human Geography, University of Bristol. February 2011 October 2007- AHRC Research Fellow, School of Geography, University of Exeter. ‘Negotiating the September 2010 Politics and Poetics of cultural identity in the creative industries in South West Britain’. October 2006- Part-time lecturer/tutor, School of Geography/Department of Art History, University of May 2007 Nottingham October 2003- Occasional lecturer/tutor, School of Geography, University of Nottingham September 2006 PUBLICATIONS A. Books ~ Pearson, M. Wylie, J, Merriman, P. and Hawkins, H. (eds) Landscaping, ( in preparation) ~ Hawkins, H. and Jones, P. (eds) Creative Methods. …. ( in preperation) 2013 Hawkins, H. and Straughan, E. (eds) Geographical Aesthetics: Bodies, Politics and Environments, Ashgate (under contract) 1 2009 Hawkins, H and Lovejoy, A. Insites. An artists’ book (Penryn: Insites Press). -

Historical Geography Research Group

HGRG Newsletter Summer 2014 Historical Geography Research Group Dear HGRG members, IN THIS ISSUE: Welcome to this ‘Summer’ edition of the Historical Geography Research Group newsletter. After an extraordinary burst of activity in the summer of 2013 marking Practising Historical our 40th year, members might expect that in the summer of 2014 we would down Geography: Bristol 2014 tools, take off our collective tweeds, and recline with a good book, one of the HGRG-sponsored HGRG monograph series perhaps. Not a bit of it. While we cannot promise cake sessions at the RGS-IBG and wine this year, the annual conference of the RGS-IBG promises a (surely) rec- ord number of sessions sponsored by the group, some 20 in total over 11 different Dissertation Prize—call themes. In particular, may I draw members’ attentions to the three ‘New and for entries Emerging Research in Postgraduate Historical Geography’ sessions on Thursday 28 August. These sessions are always a highlight of the conference, so please come along and support our postgraduate researchers. On the same day – at lunchtime, to be precise – we will hold our Annual General Meeting. If you are able to attend, please make every effort to do so for there is, as ever, much business to discuss. Before the AGM I will be circulating a draft, updated ‘Mission Statement’/ Constitution for the group. This is necessary in part for reasons of constant renewal but also to formally accommodate changes to committee positions that will be pro- posed, including some formalising and rationalising of roles and the appointing of CLICK FOR.. -

Historical Geography Research Group

HGRG SUMMER 2011 Historical Geography Research Group Letter from the chair Dear HGRG members, Traditionally the summer period is quiet for HGRG, however this year we held the ‘Teaching Historical Geography’ workshop in May at the RGS-IBG in London. 27 participants gathered to consider the place of historical geography in the higher education curriculum, funded by a grant from the Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences Subject Centre. Many thanks to the RGS-IBG for supporting the event, participants who attended during one of the Map of Iceland busiest times of the academic year, and also to those who supported the event but were not able to be there in person. A full IN THIS ISSUE report will be published in the autumn newsletter, however the long-term outcomes of this workshop will include the development ✦ Letter from the chair of an online bank of teaching resources. ✦ HGRG general information ✦ JHG announcement ✦ RGS-IBG 2011 sponsored Progress is being made with the HGRG archive project. Innes sessions details Keighren (RHUL, HGRG committee member) and I have started an ✦ Other announcements initial catalogue process to identify the range of papers and give a ✦Work in Progress rough guide to content. Thanks to the efforts of previous ✦ Thesis abstracts committee members we have the records of the group going back to the late 1960’s (in the days of ALRG) and the formal establishment of HGRG in 1972. The archive is very rich, indeed, it COPY FOR NEXT ISSUE was timely to discover the agenda for the ‘Teaching Historical Geography’ symposium held in January 1988 convened by Denis Date for new copy: Cosgrove, including contributions by Felix Diver and Mike 20th September 2011 Heffernan who also attended the workshop in May 2011. -

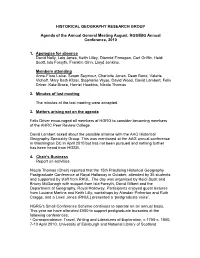

2010 AGM Minutes

HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHY RESEARCH GROUP Agenda of the Annual General Meeting August, RGS/IBG Annual Conference, 2010 1. Apologies for absence David Nally, Lois Jones, Keith Lilley, Diarmid Finnegan, Carl Griffin, Heidi Scott, Isla Forsyth, Franklin Ginn, Lloyd Jenkins. Members attending Anne-Flore Laloe, Susan Seymour, Charlotte Jones, Dean Bond, Valerie Vichoff, Mary Beth Kitzel, Stephanie Wyse, David Wood, David Lambert, Felix Driver, Kate Brace, Harriet Hawkins, Nicola Thomas 2. Minutes of last meeting The minutes of the last meeting were accepted. 3. Matters arising not on the agenda Felix Driver encouraged all members of HGRG to consider becoming members of the AHRC Peer Review College. David Lambert asked about the possible alliance with the AAG Historical Geography Speciality Group. This was mentioned at the AAG annual conference in Washington DC in April 2010 but has not been pursued and nothing further has been heard from HGSG. 4. Chair’s Business Report on activities Nicola Thomas (Chair) reported that the 15th Practising Historical Geography Postgraduate Conference at Royal Holloway in October, attended by 35 students and supported by staff from RHUL. The day was organised by Heidi Scott and Briony McDonagh with support from Isla Forsyth, David Gilbert and the Department of Geography, Royal Holloway. Participants enjoyed guest lectures from Luciana Martins and Keith Lilly; workshops by Alasdair Pinkerton and Ruth Craggs, and a Lowri Jones (RHUL) presented a ‘postgraduate voice’. HGRG’s Small Conference Scheme continues to operate on an annual basis. This year we have allocated £500 to support postgraduate bursaries at the following conferences: • Correspondence: Travel, Writing and Literatures of Exploration, c.1750-c. -

Historical Geography Research Group

HGRG NEWSLETTER WINTER 2011 Historical Geography Research Group Letter from the chair Dear HGRG members, Welcome to the Spring edition of the newsletter. I am able to report that the Practicing Historical Geography Workshop held at Nottingham University had excellent attendance and I’d like to welcome new postgraduates who attended the day to the group. You will see the report of the day in the newsletter, however I’d like to extend my thanks to the School of Geography for their generous hosting of the event and Caroline Map of Iceland Bressey, Susanne Seymour, Lucy Veale, David Matless and George Revill who all gave inspiring sessions. A special thanks to Briony McDonagh IN THIS ISSUE (Conference Officer) is due as she came back from her maternity leave to ensure the day went smoothly. ✦ Letter from the chair ✦ HGRG general information In the Autumn the committee with the RGS-IBG Research and Higher ✦ JHG announcement Education Division put in a grant to the Geography, Earth and ✦ LGHG special feature Environment Subject Centre to support the forthcoming Teaching ✦ RGS-IBG 2011 sponsored Historical Geography Workshop (19th and 20th May, 2011). We heard sessions (HGRG) before Christmas that this was successful which means we will be able to ✦ Other announcements give significant financial support for participants attending the days. Full ✦ Thesis abstracts details will shortly be sent by the HGRG e-mail list however you will find a ‘save the date’ flyer in the newsletter. Please update your details with Lloyd Jenkins ([email protected]) if you are not receiving emails. -

Historical Geography Research Group

HGRG NEWSLETTER ! AUTUMN 2010 Historical Geography Research Group Letter from the chair Dear Members, Welcome to the autumn edition of the HGRG newsletter. In this edition you will find the minutes of the Annual General Meeting held during the RGS-IBG annual conference in September. I would like to express my thanks to those who attended the AGM, which was unfortunately timetabled during the last session Map of Iceland of the conference. We were at least able to retire to the closing IN THIS ISSUE reception once the AGM had finished. At the AGM a number of committee members completed their ! Letter from the chair ! HGRG general information term of office and stepped aside. Firstly, may I thank Prof Jon ! Practicing Historical Stobart who has been Treasurer of HGRG for many years. Jon has Geography Conference gently but firmly steered the group into a more stable financial details position. I am very grateful to him for ensuring that the core ! RGS-IBG 2011 call for funding that HGRG provides to members has been secured. sessions ! Conference reports I’d like to thank Dr Diarmid Finnegan for ably managing the ! Conference announcements dissertation prize for the last five years. Diarmid will be ! Work in progress completing the judging for the 2010 competition with Prof Miles ! Thesis abstracts Ogborn and myself and we hope to announce the prize winner in the next newsletter. I am also grateful to Franklin Ginn for his COPY FOR NEXT ISSUE contribution as the Research Series Assistant Editor. Franklin has Date for new copy: now completed his PhD and therefore moves on from this role that is usually occupied by a postgraduate. -

Main Panel C

MAIN PANEL C Sub-panel 13: Architecture, Built Environment and Planning Sub-panel 14: Geography and Environmental Studies Sub-panel 15: Archaeology Sub-panel 16: Economics and Econometrics Sub-panel 17: Business and Management Studies Sub-panel 18: Law Sub-panel 19: Politics and International Studies Sub-panel 20: Social Work and Social Policy Sub-panel 21: Sociology Sub-panel 22: Anthropology and Development Studies Sub-panel 23: Education Sub-panel 24: Sport and Exercise Sciences, Leisure and Tourism Where required, specialist advisers have been appointed to the REF sub-panels to provide advice to the REF sub-panels on outputs in languages other than English, and / or English-language outputs in specialist areas, that the panel is otherwise unable to assess. This may include outputs containing a substantial amount of code, notation or technical terminology analogous to another language In addition to these appointments, specialist advisers will be appointed for the assessment of classified case studies and are not included in the list of appointments. Main Panel C Main Panel C Chair Professor Jane Millar University of Bath Deputy Chair Professor Graeme Barker* University of Cambridge Members Professor Robert Blackburn University of Liverpool Mr Stephen Blakeley 3B Impact From Mar 2021 Professor Felicity Callard* University of Glasgow Professor Joanne Conaghan University of Bristol Professor Nick Ellison University of York Professor Robert Hassink Kiel University Professor Kimberly Hutchings Queen Mary University of London From Jan 2021