Dean Court Days Harry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ilzers Apollon Mission!

Jeden Dienstag neu | € 1,90 Nr. 32 | 6. August 2019 FOTOS: GEPA PICTURES 50 Wien 15 SEITEN PREMIER LEAGUE Manchester City will den Hattrick! ab Seite 21 AUSTRIA WIEN: VÖLLIG PUNKTELOS IN DEN EUROPACUP MARCEL KOLLER VS. LASK Aufwind nach dem Machtkampf Seite 6 Ilzers Apollon TOTO RUNDE 32A+32B Garantie 13er mit 100.000 Euro! Mission! Seite 8 Österreichische Post AG WZ 02Z030837 W – Sportzeitung Verlags-GmbH, Linke Wienzeile 40/2/22, 1060 Wien Retouren an PF 100, 13 Die Premier League live & exklusiv Der Auftakt mit Jürgen Klopps Liverpool vs. Norwich Ab Freitag 20 Uhr live bei Sky PR_AZ_Coverbalken_Sportzeitung_168x31_2018_V02.indd 1 05.08.19 10:52 Gratis: Exklusiv und Montag: © Shutterstock gratis nur für Abonnenten! EPAPER AB SOFORT IST MONTAG Dienstag: DIENSTAG! ZEITUNG DIE SPORTZEITUNG SCHON MONTAGS ALS EPAPER ONLINE LESEN. AM DIENSTAG IM POSTKASTEN. NEU: ePaper Exklusiv und gratis nur für Abonnenten! ARCHIV Jetzt Vorteilsabo bestellen! ARCHIV aller bisherigen Holen Sie sich das 1-Jahres-Abo Print und ePaper zum Preis von € 74,90 (EU-Ausland € 129,90) Ausgaben (ab 1/2018) zum und Sie können kostenlos 52 x TOTO tippen. Lesen und zum kostenlosen [email protected] | +43 2732 82000 Download als PDF. 1 Jahr SPORTZEITUNG Print und ePaper zum Preis von € 74,90. Das Abonnement kann bis zu sechs Wochen vor Ablauf der Bezugsfrist schriftlich gekündigt werden, ansonsten verlängert sich das Abo um ein weiteres Jahr zum jeweiligen Tarif. Preise inklusive Umsatzsteuer und Versand. Zusendung des Zusatzartikels etwa zwei Wochen nach Zahlungseingang bzw. ab Verfügbarkeit. Solange der Vorrat reicht. Shutterstock epaper.sportzeitung.at Montag: EPAPER Jeden Dienstag neu | € 1,90 Nr. -

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description An 1896 Athens Olympic Games participation medal, in bronze, designed by N Lytras, struck by Honto-Poulus, the obverse with Nike 1 seated holding a laurel wreath over a phoenix emerging from the flames, the Acropolis beyond, the reverse with a Greek inscription within a wreath A Greek memorial medal to Charilaos Trikoupis dated 1896,in silver with portrait to obverse, with medal ribbonCharilaos Trikoupis was a 2 member of the Greek Government and prominent in a group of politicians who were resoundingly opposed to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. Instead of an a ...[more] 3 Spyridis (G.) La Panorama Illustre des Jeux Olympiques 1896,French language, published in Paris & Athens, paper wrappers, rare A rare gilt-bronze version of the 1900 Paris Olympic Games plaquette struck in conjunction with the Paris 1900 Exposition 4 Universelle,the obverse with a triumphant classical athlete, the reverse inscribed EDUCATION PHYSIQUE, OFFERT PAR LE MINISTRE, in original velvet lined red case, with identical ...[more] A 1904 St Louis Olympic Games athlete's participation medal,without any traces of loop at top edge, as presented to the athletes, by 5 Dieges & Clust, New York, the obverse with a naked athlete, the reverse with an eleven line legend, and the shields of St Louis, France & USA on a background of ivy l ...[more] A complete set of four participation medals for the 1908 London Olympic -

Premier League 2 and Professional Development League

Premier League 2 and Professional Development League No.28 Results Division 1 Blackburn Rovers 2 - 2 Southampton Brighton & Hove Albion 2 - 1 Manchester City Leicester City 3 - 2 Tottenham Hotspur Arsenal 1 - 2 Chelsea Everton 2 - 1 Derby County Wolverhampton Wanderers 1 - 2 Liverpool Division 2 Fulham 2 - 0 Aston Villa Manchester United P - P Swansea City Newcastle United 2 - 0 Sunderland Reading 0 - 1 Middlesbrough West Bromwich Albion P - P Norwich City West Ham United 2 - 2 Stoke City Season 2019/2020 - 19/02/2020 League Tables Division 1 Pld W D L GF GA GD Pts 1 Chelsea 17 9 8 0 33 20 13 35 2 Leicester City 17 9 5 3 33 20 13 32 3 Brighton & Hove Albion 17 9 1 7 32 25 7 28 4 Derby County 17 7 6 4 32 28 4 27 5 Liverpool 17 7 5 5 34 34 0 26 6 Arsenal 17 6 7 4 30 28 2 25 7 Everton 17 5 7 5 32 32 0 22 8 Blackburn Rovers 17 6 3 8 27 26 1 21 9 Manchester City 17 5 3 9 26 27 -1 18 10 Tottenham Hotspur 17 5 3 9 28 32 -4 18 11 Southampton 17 4 3 10 22 44 -22 15 12 Wolverhampton Wanderers 17 2 5 10 19 32 -13 11 Division 2 Pld W D L GF GA GD Pts 1 West Ham United 17 13 4 0 54 21 33 43 2 Manchester United 16 13 1 2 42 15 27 40 3 West Bromwich Albion 15 10 1 4 37 22 15 31 4 Stoke City 17 8 3 6 30 24 6 27 5 Middlesbrough 17 8 2 7 34 41 -7 26 6 Aston Villa 16 6 4 6 26 25 1 22 7 Newcastle United 17 7 1 9 27 32 -5 22 8 Swansea City 16 6 3 7 22 31 -9 21 9 Reading 17 5 2 10 32 36 -4 17 10 Norwich City 16 5 2 9 23 31 -8 17 11 Fulham 17 5 2 10 23 32 -9 17 12 Sunderland 17 0 1 16 10 50 -40 1 Season 2019/2020 - 19/02/2020 Fixture Changes Premier League 2 -

Annual Report 2010

Tottenham Hotspur plc tottenham TM Bill Nicholson Way 748 High Road TO DARE IS TO DO Tottenham London N17 0AP tottenhamhotspur.com hotspur plc annual report 2010 TOTTENHAM HOTSPUR PLC ANNUAL REPORT 2010 OFFICIAL PREMIER LEAGUE OFFICIAL CUP OFFICIAL CLUB SHIRT SPONSOR SHIRT SPONSOR TECHNICAL PARTNER “ This period has seen the Club produce A record turnover and A 23% increase in operating profit. dare to remember WE are benefiting now from our investment to date in the First Team Squad. Our challengE is to accrue further benefits from our investment in capital projects in order to lay the strongest foundations for the future stability and prosperity Of the Club.” DANIEL LEVY CHAIRMAN, TOTTENHAM HOTSPUR PLC CONTENTS 50TH ANNIvERSARy 1961 Football League Champions and winners of The FA Cup. OUR CLUB OUR RESULTS 1 Financial highlights 32 Consolidated income statement Summary and outlook 33 Consolidated balance sheet 2 First Team 34 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 4 Academy 35 Consolidated statement of cash flows 6 Training Ground 36 Notes to the consolidated accounts 8 Stadium 57 Five-year review 10 Our fans 58 Independent auditors’ report 14 Foundation 59 Company balance sheet 60 Notes to the Company accounts Designed and produced by OUR BUSINESS ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Photography by: Pat Graham & Action Images 66 Notice of Annual General Meeting 16 Chairman’s statement This Annual Report is printed on UPM Offset and Regency Gloss, both produced from mixed FSC sources. 71 Appendix It has been manufactured to the certified environmental management system ISO 14001. 20 Financial review 72 Directors, officers and advisers It is TCF (totally chlorine free), totally recyclable and has biodegradable NAPM recycled certification. -

2019-20 Impeccable Premier League Soccer Checklist Hobby

2019-20 Impeccable Premier League Soccer Checklist Hobby Autographs=Yellow; Green=Silver/Gold Bars; Relic=Orange; White=Base/Metal Inserts Player Set Card # Team Print Run Callum Wilson Gold Bar - Premier League Logo 13 AFC Bournemouth 3 Harry Wilson Silver Bar - Premier League Logo 8 AFC Bournemouth 25 Joshua King Silver Bar - Premier League Logo 7 AFC Bournemouth 25 Lewis Cook Auto - Jersey Number 2 AFC Bournemouth 16 Lewis Cook Auto - Rookie Metal Signatures 9 AFC Bournemouth 25 Lewis Cook Auto - Stats 14 AFC Bournemouth 4 Lewis Cook Auto Relic - Extravagance Patch + Parallels 5 AFC Bournemouth 140 Lewis Cook Relic - Dual Materials + Parallels 10 AFC Bournemouth 130 Lewis Cook Silver Bar - Premier League Logo 6 AFC Bournemouth 25 Lloyd Kelly Auto - Jersey Number 14 AFC Bournemouth 26 Lloyd Kelly Auto - Rookie + Parallels 1 AFC Bournemouth 140 Lloyd Kelly Auto - Rookie Metal Signatures 1 AFC Bournemouth 25 Ryan Fraser Silver Bar - Premier League Logo 5 AFC Bournemouth 25 Aaron Ramsdale Metal - Rookie Metal 1 AFC Bournemouth 50 Callum Wilson Base + Parallels 9 AFC Bournemouth 130 Callum Wilson Metal - Stainless Stars 2 AFC Bournemouth 50 Diego Rico Base + Parallels 5 AFC Bournemouth 130 Harry Wilson Base + Parallels 7 AFC Bournemouth 130 Jefferson Lerma Base + Parallels 1 AFC Bournemouth 130 Joshua King Base + Parallels 2 AFC Bournemouth 130 Nathan Ake Base + Parallels 3 AFC Bournemouth 130 Nathan Ake Metal - Stainless Stars 1 AFC Bournemouth 50 Philip Billing Base + Parallels 8 AFC Bournemouth 130 Ryan Fraser Base + Parallels 4 AFC -

Yesterday's Men Peter Shilton

THE biG inteRview retro YESTERDAY’S MEN PETER SHILTON European Cup glory, England heartache and “I Got MY managerial misery with a true footballing legend PRACtiCE FOR n WORDS: Richard Lenton thE EUROPEAN CUP FinAL on A PETER ccording to the British Army adage, ‘Perfect Preparation Bit OF GRAss on Prevents Piss Poor Performance’. During his time as SHILTON A ROUNDABOUT A manager of Nottingham Forest, Brian Clough followed With TWO CV the military motto to the letter. Well, kind of – he played » 1005 appearances around with the order of the words just a little. ‘Pissed Up Preparation TRACKSUit toPS in the Football Produces Perfect Performance’ became the new aphorism at the League for Leicester, City Ground… AS GOALPosts!” Stoke, Notts Forest, Southampton, Derby, It’s the afternoon of May 15, 1980, and European Cup holders Plymouth, Bolton Nottingham Forest are in Arenas de San Pedro to the north-west and Leyton Orient of Madrid, preparing for the defence of their crown against Kevin » 125 caps for Keegan’s FC Hamburg. England The atmosphere is typically relaxed; Clough insists that his players Shares the record » should treat European ties like holidays, and this sun-drenched, week- for clean sheets at World Cup finals (10) long trip has been no exception. “The key to preparation is relaxation,” he would say. But there’s ‘relaxation’ – health spas, massages, all- HONOURS round pampering – and ‘relaxation’ – lounging around a Spanish pool » FA Cup runner up quaffing European lager… with Leicester, 1969 Clough is in typically ebullient mood as the hours tick down League » towards kick-off at the Bernabeu. -

Sample Download

Contents Foreword 7 Introduction 9 1 Title Contenders 13 2 The Legend of Andy McDaft 19 3 Be Our Guest 38 4 Food & Drink & Drink 53 5 Celebrity 72 6 Hard, Harder, Hardest 96 7 Call the Cops 116 8 The Gaffer 127 9 Fight! Fight! Fight! 156 10 Banter, Tomfoolery and Hi-Jinks 173 11 The Man (or Woman) In Black (or Green or Yellow or Red) 204 12 Top Shelf 225 13 Why Can’t We All Just Get Along? 241 Postscript 275 Acknowledgements 276 Bibliography 278 1 Title Contenders Hoddledygook As we’ve established, there are an awful lot of footballer autobiographies. As well as a lot of awful footballer autobiographies. In this crowded market it’s important to try to make your book leap from the crowd like Sergio Ramos at a corner and demand attention. A catchy, interesting title can help significantly with that. On the other hand, if you’re a footballer, you’re already instantly recognisable to anybody who might buy and read it anyway, and you have access to a loyal fanbase that consistently proves itself willing to part with hard-earned money for any old rubbish they are served up (bad performances, third kits, club shop tat etc.), so why bother? And not bothering is very much the watchword for many players who clearly think that a nice snap and a simple title will do. Hence the plethora of ‘My Story’, ‘My Life in Football’ or ‘My Autobiography’ efforts clogging up the shelves. Surely we can do better than that? We’re not saying everyone needs to call their book Snod This for a Laugh,1 but come on. -

THE CITIZENS POST WCFC V Weymouth FC Saturday 4Th August 2018 Pre-Season Friendly

THE CITIZENS POST WCFC v Weymouth FC Saturday 4th August 2018 Pre-Season Friendly Winchester City Football Club is a committee run members club and as such is an unincorporated association. THE CITIZENS POST TODAY’S VISITORS – WEYMOUTH FC CLUB HISTORY For Weymouth FC full club history, visit: http://theterras.com/index.php/club- info/history-previous-seasons/ THE CITIZENS POST TODAY’S VISITORS – WEYMOUTH FC PLAYER PROFILES Management Profiles MARK MOLESLEY - First Team Manager – An England C international with 4 caps Mark is a vastly experienced midfielder signed by the Terras in July 2015 following his release by Aldershot Town. Mark became First Team Manager following the departure of Jason Matthews in April 2017 and has impressed with his professional attitude. Mark started his career with Hayes, coming through their youth system. Spells with Cambridge City, Aldershot Town, Stevenage Borough and Grays Athletic before being transferred to Bournemouth. He made his debut for Bournemouth, away to Shrewsbury Town, in the 4-1 defeat in the League Two on 18 October 2008. Molesley signed for Exeter City on 18 January 2013. On 30 April 2013, he was released by Exeter due to the expiry of his contract and joined Aldershot Town. Mark made 40 appearances for the Shots and scored 8 goals. Mark joined Weymouth in Summer 2015 and played for two seasons before retiring to take over as First Team Manager. Mark combines his role at Weymouth with Bournemouth Under 23s. TOM PRODOMO – Assistant Manager – Previously First-Team Manager at Bashley FC in the Sydenhams Football League. PAUL MAITLAND – Director of Football – Has also been an Assistant Manager and Caretaker Manager during his time at the club. -

Intermediary Transactions 2019-20 1.9MB

24/06/2020 01/03/2019AFC Bournemouth David Robert Brooks AFC Bournemouth Updated registration Unique Sports Management IMSC000239 Player, Registering Club No 04/04/2019AFC Bournemouth Matthew David Butcher AFC Bournemouth Updated registration Midas Sports Management Ltd IMSC000039 Player, Registering Club No 20/05/2019 AFC Bournemouth Lloyd Casius Kelly Bristol City FC Permanent transfer Stellar Football Limited IMSC000059 Player, Registering Club No 01/08/2019 AFC Bournemouth Arnaut Danjuma Groeneveld Club Brugge NV Permanent transfer Jeroen Hoogewerf IMS000672 Player, Registering Club No 29/07/2019AFC Bournemouth Philip Anyanwu Billing Huddersfield Town FC Permanent transfer Neil Fewings IMS000214 Player, Registering Club No 29/07/2019AFC Bournemouth Philip Anyanwu Billing Huddersfield Town FC Permanent transfer Base Soccer Agency Ltd. IMSC000058 Former Club No 07/08/2019 AFC Bournemouth Harry Wilson Liverpool FC Premier league loan Base Soccer Agency Ltd. IMSC000058 Player, Registering Club No 07/08/2019 AFC Bournemouth Harry Wilson Liverpool FC Premier league loan Nicola Wilson IMS004337 Player Yes 07/08/2019 AFC Bournemouth Harry Wilson Liverpool FC Premier league loan David Threlfall IMS000884 Former Club No 08/07/2019 AFC Bournemouth Jack William Stacey Luton Town Permanent transfer Unique Sports Management IMSC000239 Player, Registering Club No 24/05/2019AFC Bournemouth Mikael Bongili Ndjoli AFC Bournemouth Updated registration Tamas Byrne IMS000208 Player, Registering Club No 26/04/2019AFC Bournemouth Steve Anthony Cook AFC Bournemouth -

Team Checklist I Have the Complete Set 1975/76 Monty Gum Footballers 1976

Nigel's Webspace - English Football Cards 1965/66 to 1979/80 Team checklist I have the complete set 1975/76 Monty Gum Footballers 1976 Coventry City John McLaughlan Robert (Bobby) Lee Ken McNaught Malcolm Munro Coventry City Jim Pearson Dennis Rofe Jim Brogan Neil Robinson Steve Sims Willie Carr David Smallman David Tomlin Les Cartwright George Telfer Mark Wallington Chris Cattlin Joe Waters Mick Coop Ipswich Town Keith Weller John Craven Ipswich Town Steve Whitworth David Cross Kevin Beattie Alan Woollett Alan Dugdale George Burley Frank Worthington Alan Green Ian Collard Steve Yates Peter Hindley Paul Cooper James (Jimmy) Holmes Eric Gates Manchester United Tom Hutchison Allan Hunter Martin Buchan Brian King David Johnson Steve Coppell Larry Lloyd Mick Lambert Gerry Daly Graham Oakey Mick Mills Alex Forsyth Derby County Roger Osborne Jimmy Greenhoff John Peddelty Gordon Hill Derby County Brian Talbot Jim Holton Geoff Bourne Trevor Whymark Stewart Houston Roger Davies Clive Woods Tommy Jackson Archie Gemmill Steve James Charlie George Leeds United Lou Macari Kevin Hector Leeds United David McCreery Leighton James Billy Bremner Jimmy Nicholl Francis Lee Trevor Cherry Stuart Pearson Roy McFarland Allan Clarke Alex Stepney Graham Moseley Eddie Gray Anthony (Tony) Young Henry Newton Frank Gray David Nish David Harvey Middlesbrough Barry Powell Norman Hunter Middlesbrough Bruce Rioch Joe Jordan David Armstrong Rod Thomas - 3 Peter Lorimer Stuart Boam Colin Todd Paul Madeley Peter Brine Everton Duncan McKenzie Terry Cooper Gordon McQueen John Craggs Everton Paul Reaney Alan Foggon John Connolly Terry Yorath John Hickton Terry Darracott Willie Maddren Dai Davies Leicester City David Mills Martin Dobson Leicester City Robert (Bobby) Murdoch David Jones Brian Alderson Graeme Souness Roger Kenyon Steve Earle Frank Spraggon Bob Latchford Chris Garland David Lawson Len Glover Newcastle United Mick Lyons Steve Kember Newcastle United This checklist is to be provided only by Nigel's Webspace - http://cards.littleoak.com.au/. -

Premier League, 2018–2019

Premier League, 2018–2019 “The Premier League is one of the most difficult in the world. There's five, six, or seven clubs that can be the champions. Only one can win, and all the others are disappointed and live in the middle of disaster.” —Jurgen Klopp Hello Delegates! My name is Matthew McDermut and I will be directing the Premier League during WUMUNS 2018. I grew up in Tenafly, New Jersey, a town not far from New York City. I am currently in my junior year at Washington University, where I am studying psychology within the pre-med track. This is my third year involved in Model UN at college and my first time directing. Ever since I was a kid I have been a huge soccer fan; I’ve often dreamed of coaching a real Premier League team someday. I cannot wait to see how this committee plays out. In this committee, each of you will be taking the helm of an English Football team at the beginning of the 2018-2019 season. Your mission is simple: climb to the top of the world’s most prestigious football league, managing cutthroat competition on and off the pitch, all while debating pressing topics that face the Premier League today. Some of the main issues you will be discussing are player and fan safety, competition with the world’s other top leagues, new rules and regulations, and many more. If you have any questions regarding how the committee will run or how to prepare feel free to email me at [email protected]. -

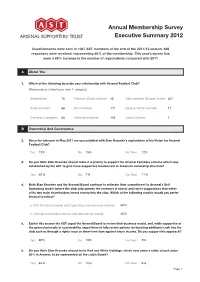

Annual Membership Survey Executive Summary 2012

Annual Membership Survey Executive Summary 2012 Questionnaires were sent to 1067 AST members at the end of the 2011/12 season. 636 responses were received, representing 60% of the membership. This year’s survey has seen a 65% increase in the number of respondents compared with 2011 A About You 1. Which of the following describe your relationship with Arsenal Football Club? (Respondents ticked more than 1 category) Shareholder:70 Platinum (Club) member:45 Gold member (Season ticket): 301 Silver member:66 Red member:171 Away scheme member: 17 Overseas supporter:60 Fanshare member:105 Junior Gunner: 1 B Ownership And Governance 2. Since his takeover in May 2011 are you satisfi ed with Stan Kroenke’s explanation of his Vision for Arsenal Football Club? Yes: 13%No: 75% No View: 12% 3. Do you think Stan Kroenke should make it a priority to support the Arsenal Fanshare scheme which was established by the AST to give more supporters involvement in Arsenal’s ownership structure? Yes: 82%No: 7% No View: 11% 4. Both Stan Kroenke and the Arsenal Board continue to reiterate their commitment to Arsenal’s Self- Sustaining model (where the club only spends the revenues it raises) and reject suggestions that either of its two main shareholders invest money into the club. Which of the following models would you prefer Arsenal to follow? a. Self-Sustaining model (only spending club revenues earned) 60% b. Outside investment into the club (benefactor model) 40% 5. Earlier this season the AST urged the Arsenal Board to review their business model, and, while supportive of the general principle of sustainability, urged them to fully review options for injecting additional cash into the club such as through a rights issue or short-term loan against future income.