Negotiating the “Negro Problem”: Stew's Passing (Made) Strange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OSLO Big Winner at the 2017 Lucille Lortel Awards, Full List! by BWW News Desk May

Click Here for More Articles on 2017 AWARDS SEASON OSLO Big Winner at the 2017 Lucille Lortel Awards, Full List! by BWW News Desk May. 7, 2017 Tweet Share The Lortel Awards were presented May 7, 2017 at NYU Skirball Center beginning at 7:00 PM EST. This year's event was hosted by actor and comedian, Taran Killam, and once again served as a benefit for The Actors Fund. Leading the nominations this year with 7 each are the new musical, Hadestown - a folk opera produced by New York Theatre Workshop - and Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, currently at the Barrow Street Theatre, which has been converted into a pie shop for the intimate staging. In the category of plays, both Paula Vogel's Indecent and J.T. Rogers' Oslo, current Broadway transfers, earned a total of 4 nominations, including for Outstanding Play. Playwrights Horizons' A Life also earned 4 total nominations, including for star David Hyde Pierce and director Anne Kauffman, earning her 4th career Lortel Award nomination; as did MCC Theater's YEN, including one for recent Academy Award nominee Lucas Hedges for Outstanding Lead Actor. Lighting Designer Ben Stanton earned a nomination for the fifth consecutive year - and his seventh career nomination, including a win in 2011 - for his work on YEN. Check below for live updates from the ceremony. Winners will be marked: **Winner** Outstanding Play Indecent Produced by Vineyard Theatre in association with La Jolla Playhouse and Yale Repertory Theatre Written by Paula Vogel, Created by Paula Vogel & Rebecca Taichman Oslo **Winner** Produced by Lincoln Center Theater Written by J.T. -

“Kiss Today Goodbye, and Point Me Toward Tomorrow”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By BRYAN M. VANDEVENDER Dr. Cheryl Black, Dissertation Supervisor July 2014 © Copyright by Bryan M. Vandevender 2014 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 Presented by Bryan M. Vandevender A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Cheryl Black Dr. David Crespy Dr. Suzanne Burgoyne Dr. Judith Sebesta ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I incurred several debts while working to complete my doctoral program and this dissertation. I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to several individuals who helped me along the way. In addition to serving as my dissertation advisor, Dr. Cheryl Black has been a selfless mentor to me for five years. I am deeply grateful to have been her student and collaborator. Dr. Judith Sebesta nurtured my interest in musical theatre scholarship in the early days of my doctoral program and continued to encourage my work from far away Texas. Her graduate course in American Musical Theatre History sparked the idea for this project, and our many conversations over the past six years helped it to take shape. -

Musical! Theatre!

Premier Sponsors: Sound Designer Video Producer Costume Coordinator Lance Perl Chrissy Guest Megan Rutherford Production Stage Manager Assistant Stage Manager Stage Management Apprentice Mackenzie Trowbridge* Kat Taylor Lyndsey Connolly Production Manager Dramaturg Assistant Director Adam Zonder Hollyann Bucci Jacob Ettkin Musical Director Daniel M. Lincoln Directors Gerry McIntyre+ & Michael Barakiva+ We wish to express our gratitude to the Performers’ Unions: ACTORS’ EQUITY ASSOCIATION AMERICAN GUILD OF MUSICAL ARTISTS AMERICAN GUILD OF VARIETY ARTISTS SAG-AFTRA through Theatre Authority, Inc. for their cooperation in permitting the Artists to appear on this program. * Member of the Actor's Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. + ALEXA CEPEDA is delighted to be back at The KRIS COLEMAN* is thrilled to return to the Hangar. Hangar! Select credits: Mamma Mia (CFRT), A Broadway Credit: Jersey Boys (Barry Belson) Chorus Line (RTP), In The Heights (The Hangar Regional Credit: Passing Strange (Narrator), Jersey Theatre), The Fantasticks (Skinner Boys - Las Vegas (Barry Belson), Chicago (Hangar Barn), Cabaret (The Long Center), Anna in the Theatre, Billy Flynn), Dreamgirls (Jimmy Early), Sister Tropics (Richard M Clark Theatre). She is the Act (TJ), Once on This Island (Agwe), A Midsummer founder & host of Broadway Treats, an annual Nights Dream (Oberon) and Big River (Jim). benefit concert organized to raise funds for Television and film credits include: The Big House Animal Lighthouse Rescue (coming up! 9/20/20), and is (ABC), Dumbbomb Affair, and The Clone. "As we find ourselves currently working on her two-person musical Room 123. working through a global pandemic and race for equality, work Proud Ithaca College BFA alum! "Gracias a mamacita y papi." like this shows the value and appreciation for all. -

Annie Dorsen Holland Festival 2015

HOLLAND FESTIVAL 2015 YESTERDAY T0MORROW ANNIE DORSEN met bijdrage van with additional support by The MAP Fund, with the assistance of the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; INFO Mount Tremper Arts; Abrons Arts Center; New York State DO 4.6 Council on the Arts, with the support of Governor Andrew THU 4.6 Cuomo and the New York State Legislature aanvang starting time met dank aan thank you 20:30 8:30 pm Dylan Fried, Tian Jiang, Greg Purnhagen, Tomas Cruz, Wiesenburg, The Bach Project locatie venue Muziekgebouw aan ‘t IJ wereldpremière world premiere Amsterdam, 4 juni 2015 duur running time 60 minuten, geen pauze 60 minutes, no interval inleiding introduction door by Thea Derks ANNIE DORSEN: 19:45 7:45 pm YESTERDAY TOMORROW, EEN CREDITS ALGORITMISCHE concept, regie concept, direction Annie Dorsen MUSICAL muzikale leiding music director door Thea Derks Joanna Bailie Regisseur Annie Dorsen is bekend vanwege haar ‘algoritmisch algoritme-ontwerp algorithm design theater’, waarin ze bestaande teksten uit elkaar pluist en Pierre Godard weer in elkaar zet met behulp van computers. In Hello Hi There (2010) wierp ze een nieuw licht op een historisch geluidsontwerp sound design gesprek tussen de Franse filosoof Michel Foucault en de Greg Beller Amerikaanse linguïst Noam Chomsky. Op het toneel zien we twee laptops via chatbots discussiëren over serieuze ontwerp videosysteem video systems design onderwerpen. Doordat zij de meest onverwachte zijpaden Ryan Holsopple bewandelen, bevragen zij de optimistische verwachting dat machines uiteindelijk de mens kunnen vervangen. lichtontwerp en technische productie lighting design and Tegelijkertijd illustreren ze de onmogelijkheid van werkelijke technical direction communicatie en verbinding. -

The Hamilcast's Transcribing Army

The Hamilcast: An American Podcast #21: What are the odds the gods would put us all in one spot? Hosts: Gillian Pennsavalle and Bianca Soto Description: This is a milestone episode! Seth Stewart (@IAMSethStewart) is the first Hamilton cast member to come on the podcast! Seth talks backstage at the Tonys, his responsibilities as the Green Captain of “Hamilton”, the moment he realized he’d be best friends with Lin-Manuel Miranda, and why we should all #StayWeird. He also speaks directly to the Hamilfans. Jam!!! Transcribed by: Autumn Clarke, Proofed by: Joan Crofton The Hamilcast’s Transcribing Army Ok, so we are doing this . ___________________________________________________ GILLIAN PENSAVALLE: Hey, everybody! BIANCA SOTO: Hey! G.PEN: Hi! B.SO: How are you? G.PEN: I’m awesome! B.SO: Yeah me too! G.PEN: How are you? B.SO: I’m great! G.PEN: I’m Gillian B.SO: I’m Bianca G.PEN: This is a big ep B.SO: Big ep! G.PEN: Milestone ep B.SO: For sure! We’re at Shetler Studios here in NYC. For those of you who don’t know, it’s a rehearsal studio space G.PEN: It’s not just a milestone because we’re not in my living room in my apartment, but we have an actual cast member of Hamilton in the flesh, Seth Stewart. SETH STEWART: Jam! G.PEN AND B.SO: [Excited noises] G.PEN: How are you? S.STEW: Good! G.PEN: Thank you so much for being here S.STEW: Of course G.PEN: It’s a really big deal S.STEW: Of course G.PEN: So, again, I’m apologizing for audio. -

Passing Strange Wins 2008 Tony Award for Best Book of a Musical

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For More Information Contact: JUNE 15, 2008 Amy McGee [email protected]/310-492-2333 PASSING STRANGE WINS 2008 TONY AWARD FOR BEST BOOK OF A MUSICAL June 15, 2008 - New York – PASSING STRANGE and Stew , tonight received the 2008 Tony Award for Best Book of a Musical . Sundance's latest project to land on Broadway, PASSING STRANGE was cultivated at the 2004 and 2005 Sundance Institute Theatre Labs. The Tony Awards were announced in a three-hour CBS telecast from Radio City Music Hall. Whoopi Goldberg served as host. "We congratulate Stew and Heidi and the entire cast on PASSING STRANGE. We're so happy they are part of the Sundance family and for all of their recent successes," said Philip Himberg. "PASSING STRANGE is unlike other Broadway musicals; it is significant that the show is enjoying critical success. And it is exciting that audiences are hungry for work that's completely unique." Stew, who wrote the book of PASSING STRANGE with Heidi Rodewald, accepted the award at a pre-broadcast ceremony. "I don't know what to say, because I didn't know we were going to do this right now," he said. "I thought this was going to happen in an hour or something. I was looking for some M & M's in my pocket." Later in the awards program Stew appeared sporting a fake nose and moustache. PASSING STRANGE is currently on Broadway at The Belasco Theatre, 111 West 44th Street, New York City. The Antoinette Perry Awards for Excellence in Theatre, more commonly known as the Tony Awards, recognize achievement in live American theatre and are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League. -

Mark Sonnenblick Contact Mark Orsini at Bret Adams, Ltd

Mark Sonnenblick Contact Mark Orsini at Bret Adams, Ltd. [email protected] PROFESSIONAL THEATER • Independents (lyricist, revised book) FringeNYC/SoHo Playhouse 2012. Won “Best Overall Production,” the Fringe’s highest honor. Extended off-Broadway and designated a NYTimes “Critics’ Pick.” • Midnight at The Never Get (composer, lyricist, bookwriter) New York Musical Festival July 2016. Special event; played for three sold-out nights. Being developed for a full production in 2017. • Ship Show (lyricist, bookwriter) Yale Institute for Music Theatre June 2015. Directed by Mark Brokaw. • Stompcat in Lawndale (lyricist, bookwriter, co-composer) Ars Nova 2014, various bars Ant Fest June 2014; played in bars all over New York. Immersive rock musical experience. • Wheel of Misfortune (co-writer, composer, performer) Denver Center for the Performing Arts 2013. New multimedia performance piece in the style of a live game show. • NYC Cabaret Circuit (composer, lyricist) Songs performed at Lincoln Center, Symphony Space, NYMF (’12 and ’13), Don’t Tell Mama, Duplex, etc. PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT • American Opera Initiative (librettist) Washington National Opera Commissioned for 2015—opera premiered at the Kennedy Center in December 2015. • Johnny Mercer Writers Colony Goodspeed Musicals February 2016. • Dramatists Guild Fellowship (lyricist, bookwriter) 2014-2015. Developed Ship Show with composer Ben Wexler. Led by Michael Korie and Diana Son. • Rhinebeck Writers Retreat Summer 2016. Previous attendees include Duncan Sheik, Michael Friedman, Heidi Rodewald/Stew. • Composers And The Voice (librettist fellow) American Opera Projects 2015-2017. Led by Stephen Osgood, Mark Campbell. • Johnny Mercer Songwriting Project American Music Theatre Project June 2014. Weeklong songwriting intensive. Studied with Craig Carnelia, Andrew Lippa, Lari White. -

Wedding Band Bio Poster.Indd

PLAY BY THE BOOK: UPRISING SERIES Wedding Band by Alice Childress MARION ADLER HERMANN’S MOTHER ALLISON EDWARDSCREWE MATTIE Stratford: Grandma Elliot in Billy Elliot the Musical, lyricist for The Merry Wives of Allison has traveled across Canada performing on stage and screen. Selected Windsor, Lady Markby in An Ideal Husband, Mrs. Dubose in To Kill a Mockingbird, credits: Theatre: Serving Elizabeth (Western Canada Theatre); The Color Purple Cicero, Volumnius in Julius Caesar, Lady Capulet in Romeo and Juliet, Gabrielle (Citadel Theatre and Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre); School Girls; Or, the African in The Madwoman of Chaillot, Diana in and lyricist for The Adventures of Pericles. Mean Girls Play (Obsidian and Nightwood Theatre); How Black Mothers Say Elsewhere: Paulina and Hermione in The Winter’s Tale, Queen Marguerite in I Love You (Factory Theatre); All Shook Up (The Globe Theatre); Miss Bennet: Exit the King, Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing, Philaminte in The Learned Christmas at Pemberley (Citadel); Girls Like That (Tarragon Theatre); ’da Kink in Ladies, Titania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Shakespeare Theatre of New My Hair (Theatre Calgary, National Arts Centre); Dreamgirls (Grand Theatre). Film/ Jersey); Princess of France in Love’s Labour’s Lost, Emilia in Othello, Mistress TV: The Handmaid’s Tale (MGM/Hulu), Baby in a Manger (BrainPower), Surviving Quickly in Henry IV Part 2 (Shakespeare Santa Cruz). Et cetera: Ms Adler is an Evil (Cinefl ix), Black Actress (JungleWild). Audio Dramas: Liming (Expect Theatre/CBC), Every Second internationally acclaimed, award-winning lyricist. of Every Day (Factory Theatre). Training: High Honours Bachelor of Music Theatre, Sheridan College. -

Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation Within American Tap Dance Performances of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 © Copyright by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 by Brynn Wein Shiovitz Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Susan Leigh Foster, Chair Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950, looks at the many forms of masking at play in three pivotal, yet untheorized, tap dance performances of the twentieth century in order to expose how minstrelsy operates through various forms of masking. The three performances that I examine are: George M. Cohan’s production of Little Johnny ii Jones (1904), Eleanor Powell’s “Tribute to Bill Robinson” in Honolulu (1939), and Terry- Toons’ cartoon, “The Dancing Shoes” (1949). These performances share an obvious move away from the use of blackface makeup within a minstrel context, and a move towards the masked enjoyment in “black culture” as it contributes to the development of a uniquely American form of entertainment. In bringing these three disparate performances into dialogue I illuminate the many ways in which American entertainment has been built upon an Africanist aesthetic at the same time it has generally disparaged the black body. -

THOSE MAGIC CHANGES in Case You Haven't Noticed, the American Musical Is Changing Keys and Adding New Voices

THOSE MAGIC CHANGES In case you haven't noticed, the American musical is changing keys and adding new voices. SCOTT MILLER's small theatre in St. Louis is keeping score. BY ROB WEINERT-KENDT HEN THE MUSICAL HIGH FIDELITY CLOSED Though composer abruptly after just 13 unlucky performances on Broad Kitt didn't make the pil Wway, composer Tom Kitt and lyricist Amanda Green grimage, he followed the were nursing their wounds-and then they got a call from St. Louis, show's fortunes admiringly Mo. Somebody there loved, loved, loved their show, and wanted to from afar. mount the first regional production. Though this stage adaptation "Having someone of the beloved ick Hornby novel and Stephen Frears film about a come forward and say, 'I passionate pop-music fan and his rocky love life had been roundly love it and want to do it' panned by critics and resoundingly rejected by audiences in New was really important to the York, a guy named Scott Miller desperatt;ly wanted to do the first show," confirms Kitt, who regional production at his scrappy little New Line Theatre. went on to write Next to The show wasn't yet officially licensed (it's now available via Normal (seen at New Line Playscripts) and the score still needed some cleanup, but Miller in 2013) and the current nabbed the rights, and his 2008 production got raves from St. Louis Broadway outing If/Then. critics. And it still gets high marks from lyricist Green, who attended. "And not only did Scott "Seeing it there in a bare-bones production, a very respectful Miller do it-he did a production that was unanimously praised in production-I don't mean respectful in a boring way, but very atten St. -

Hollywood Pantages Theatre Los Angeles, California

® HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 3.12.20 - 3.31.20 Hamilton @ Pantages LA.indd 1 2/27/20 4:29 PM HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE March 12-March 31, 2020 Jeffrey Seller Sander Jacobs Jill Furman AND The Public Theater PRESENT BOOK, MUSIC AND LYRICS BY Lin-Manuel Miranda INSPIRED BY THE BOOK ALEXANDER HAMILTON BY Ron Chernow WITH Rubén J. Carbajal Nicholas Christopher Joanna A. Jones Taylor Iman Jones Carvens Lissaint Simon Longnight Rory O’Malley Sabrina Sloan Wallace Smith Jamael Westman AND Sam Aberman Gerald Avery Amanda Braun Cameron Burke Yossi Chaikin Trey Curtis Jeffery Duffy Karlee Ferreira Tré Frazier Aaron Alexander Gordon Sean Green, Jr. Jared Howelton Sabrina Imamura Jennifer Locke Yvette Lu Taeko McCarroll Mallory Michaellann Antuan Magic Raimone Julian Ramos Jen Sese Willie Smith III Terrance Spencer Raven Thomas Tommar Wilson Mikey Winslow Morgan Anita Wood SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN David Korins Paul Tazewell Howell Binkley Nevin Steinberg HAIR AND WIG DESIGN ARRANGEMENTS MUSIC COORDINATORS ASSOCIATE MUSIC SUPERVISOR Charles G. LaPointe Alex Lacamoire Michael Keller Matt Gallagher Lin-Manuel Miranda Michael Aarons EXECUTIVE PRODUCER PRODUCTION SUPERVISOR PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER MUSIC DIRECTOR Maggie Brohn J. Philip Bassett Scott Rowen Andre Cerullo MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS TECHNICAL SUPERVISION CASTING Laura Matalon Hudson Theatrical Associates Telsey + Company John Gilmour Bethany Knox, CSA ASSOCIATE & SUPERVISING DIRECTOR ASSOCIATE & SUPERVISING CHOREOGRAPHER Patrick Vassel -

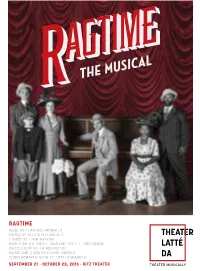

Ragtime Program

RAGTIME BOOK BY TERRENCE MCNALLY MUSIC BY STEPHEN FLAHERTY THEATER LYRICS BY LYNN AHRENS BASED ON THE NOVEL “RAGTIME” BY E. L. DOCTOROW LATTÉ DIRECTED BY PETER ROTHSTEIN MUSIC DIRECTION BY DENISE PROSEK CHOREOGRAPHY BY KELLI FOSTER WARDER DA SEPTEMBER 21 – OCTOBER 23, 2016 • RITZ THEATER THEATER MUSICALLY Theater Latté Da presents RAGTIME Book by Terrence McNally Music by Stephen Flaherty Lyrics by Lynn Ahrens Based on the novel “Ragtime” by E. L. Doctorow Directed by Peter Rothstein** Music Direction by Denise Prosek*** Choreography by Kelli Foster Warder FEATURING Sasha Andreev*, Debra Berger, Georgia Blando, Benjamin Dutcher, Daniel S. Hines*, Emily Jansen, Riley McNutt, Soren Thayne Miller, David L. Murray, Jr., Britta Ollmann*, James Ramlet, Noelle Renae Hunter, Traci Allen Shannon*, Andre Shoals*, Dominic Tidmarsh-Kilander, and Julia Fé Foster Warder *Member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors ** Member of SDC, the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society, a national theatrical labor union ***Member of Twin Cities Musicians Union, American Federation of Musicians RAGTIME will be performed with one intermission Opening Night: Saturday, September 24, 2016 ASL Interpreted and Audio Described Performance: Thursday, October 6, 2016 Post-Show Discussions: Wednesdays, September 28, October 5, 12, and 19; Thursdays, September 29, October 6, 13, and 20; Sundays, September 25, October 2, 9, and 16 RAGTIME is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International [MTI]. All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI, New York, NY. Tel: 212-541-4684. Fax: 212-397-4684. www.mtishows.com The video and/or audio recording of this performance by any means whatsoever is strictly prohibited.