This Northside Subdivision on Sibbald Avenue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Want to Be a Part of It: Popular Music and Me an Honors Thesis (HONRS

- I Want to Be a Part of It: Popular Music and Me An Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) by William L. Allen Thesis Advisors Dr. Tony Edmonds Mr. Stan Sollars Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April 1996 May 1996 (expected graduation date) " , " - I .~.!~, Author's Note: IA6~ What you are about to read is basically my autobiography. It concerns my relationship with popular music, which, outside of family and friends, is the most important part of my life. It's a relationship that has been going on for more than two decades, and I feel it is worth close examination on my part. For my senior thesis, I decided to perform my own concert. I would like more than anything in life to be an entertainer. Since show business is so hard to get into (and be successful), I thought I should perform while I still had the chance--before I had to settle down and get a real job. The written part, which you are now reading, is very informal. Throughout high school, I was always told not to use contractions and not to write in the informal second person. I've always questioned this. After all, it's my work. Who has the right to tell me what I can and can not put in it? I write in a very conversational style. When I tell a story, it helps if I feel as though I'm conversing with or writing a letter to you, the reader. Consequently, I use the pronoun "you" from time to time. I use contractions because that's how we as human beings speak. -

Technical Rider

TECHNICAL RIDER (SUBJECT TO CHANGES AS REQUIRED) Schirmer Theatrical, LLC part of the Music Sales Group 180 Madison Avenue, 24th Floor New York, NY 10016 Email: [email protected] www.schirmertheatrical.com Greenberg Artists 36 Bender Way Pound Ridge, NY 10576 Tel. 646.504.8084 Email: [email protected] www.greenbergartists.com/shows Initial: ______ 1.DEFINITIONS At all times, the definition of the word “PRESENTER” shall refer to the legal entity that is engaging this production, which includes musicians, staff, management, etc. “VENUE” shall refer to the concert hall and location in which the production shall take place. “PRODUCTION” shall refer to the orchestral concert Paul Simon Songbook. “PRODUCERS” shall jointly refer to the co-producers Greenberg Artists and Schirmer Theatrical, LLC, both legal entities incorporated and operating under the laws and jurisdiction of the State of New York. All equipment, materials, personnel and/or labor specified in this rider will be provided by the PRESENTER, at the PRESENTER’s own expense (except where rider specifically notes otherwise). Upon completion of the agreement or sixty (60) days prior to performance, the PRESENTER shall provide to the PRODUCERS plans and information about the VENUE including a stage and seating diagram, backline lists of lighting, audio equipment, and any additional information such as working hours or labor stipulations that may be vital to the planning of this engagement. All audio and lighting components, as described below, must be set-up, tested, and fully operational before first rehearsal of the PRODUCTION, whether that rehearsal is with or without the orchestra (see Rehearsals). -

How They Got Over: a Brief Overview of Black Gospel Quartet Music

How They Got Over: A Brief Overview of Black Gospel Quartet Music Jerry Zolten October 29, 2015 Jerry Zolten is Associate Professor of Communication Arts & Sciences, American Studies, and Integrative Arts at the Penn State-Altoona. his piece takes you on a tour through black gospel music history — especially the gospel quartets T — and along the way I’ll point you to some of the most amazing performances in African American religious music ever captured on film. To quote the late James Hill, my friend and longtime member of the Fairfield Four gospel quartet, “I don't want to make you feel glad twice—glad to see me come and glad to see me go.” With that in mind I’m going to get right down to the evolution from the spirituals of slavery days to the mid-twentieth century “golden age” of gospel. Along the way, we’ll learn about the a cappella vocal tradition that groups such as the Fairfield Four so brilliantly represent today. The black gospel tradition is seeded in a century and a half of slavery and that is the time to begin: when the spirituals came into being. The spirituals evolved out of an oral tradition, sung solo or in groups and improvised. Sometimes the music is staid, sometimes histrionic. Folklorist Zora Neale Hurston famously described how spirituals were never sung the same way twice, “their truth dying under training like flowers under hot water.”1 We don’t know the names of the people who wrote these songs. They were not written down at the time. -

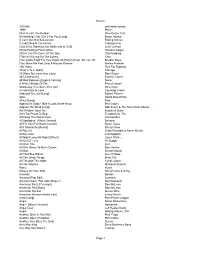

Radio Starz Karaoke Song Book

Radio Starz Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID Aerosmith Barenaked Ladies Angel RSZ613-12 What A Good Boy RSZ604-11 Baby, Please Don't Go RSZ613-01 When I Fall RSZ604-09 Back In The Saddle RSZ613-16 Beatles, The Big Ten Inch Record RSZ613-13 All You Need Is Love RSZ623-08 Cryin' RSZ613-17 And I Love Her RSZ623-06 Dream On RSZ613-04 And Your Bird Can Sing RSZ622-17 Dude (Looks Like A Lady) RSZ613-06 Another Girl RSZ621-16 I Don't Want To Miss A Thing RSZ613-10 Back In The USSR RSZ622-02 Jaded RSZ613-07 Birthday RSZ622-05 Janie's Got A Gun RSZ613-14 Can't Buy Me Love RSZ622-09 Last Child RSZ613-03 Come Together RSZ621-14 Love In An Elevator RSZ613-09 Day Tripper RSZ621-07 Mama Kin RSZ613-11 Do You Want To Know A Secret RSZ623-11 Same Old Song And Dance RSZ613-15 Don't Let Me Down RSZ623-09 Sweet Emotion RSZ613-05 Eight Days A Week RSZ623-05 Train Kept A Rollin' RSZ613-18 Eleanor Rigby RSZ622-13 Walk This Way RSZ613-08 From Me To You RSZ623-15 What It Takes RSZ613-02 Get Back RSZ622-04 Alanis Morissette Golden Slumbers, Carry That Weight, The End RSZ621-20 All I Really Want RSZ626-13 Good Day Sunshine RSZ621-06 Everything RSZ626-11 Hard Days Night, A RSZ623-03 Forgiven RSZ626-12 Hello Goodbye RSZ622-06 Hand In My Pocket RSZ626-05 Help! RSZ621-04 Hands Clean RSZ626-08 Helter Skelter RSZ622-08 Hands Clean RSZ626-08A Here, There & Everywhere RSZ623-18 Hands Clean RSZ626-08B Hey Jude RSZ622-01 Head Over Feet RSZ626-07 I Feel Fine RSZ622-10 Ironic RSZ626-02 I Saw Her Standing There RSZ621-01 Precious Illusions -

040719.Log ********** 88.5 Fm Keom 04/07/19

040719.LOG ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 04/07/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 12:00 A 72 I'll Take You There Staple Singers 12:03 A 75 Once You Get Started Rufus 12:07 A 74 Dancing Machine Jackson 5 12:09 A 82 Rock This Town Stray Cats 12:16 A 66 The Sound Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 12:19 A Steppin' Out (Gonna Boogie Tonight) Tony Orlando & Dawn 12:22 A 83 Tender Is The Night Jackson Browne 12:26 A 72 The Way Of Love Cher 12:31 A 73 Neither One Of Us (Wants To Be The Gladys Knight & The Pips 12:35 A 97 I Want You Savage Garden 12:39 A 80 More Than I Can Say Leo Sayer 12:42 A 78 Sweet Life Paul Davis 12:46 A 96 Insensitive Jann Arden 12:50 A 79 Stumblin' In Suzi Quatro & Chris Norman 12:53 A Sister Golden Hair America 12:58 A Cover Girl New Kids On The Block ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 04/07/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 01:00 A 75 Dance With Me Orleans 01:03 A Jackie Blue Ozark Mountain Daredevils 01:06 A 81 Hard To Say Dan Fogelberg Page 1 040719.LOG 01:10 A 93 Baby I'm Yours Shai 01:16 A 89 If You Don't Know Me By Now Simply Red 01:19 A 73 Goodbye Yellow Brick Road Elton John 01:22 A 69 Come Together Beatles 01:27 A 78 You're The One That I Want John Travolta & Olivia Newton-John 01:29 A Piece Of My Heart Tara Kemp 01:31 A 86 Will You Still Love Me Chicago 01:35 A 87 Something So Strong Crowded House 01:38 A If Wishes Came True Sweet Sensation 01:46 A 77 You Made Me Believe In Magic Bay City Rollers 01:49 A 75 Jive Talkin' Bee Gees 01:52 A 74 Waterloo ABBA 01:54 A 84 Desert Moon Dennis DeYoung ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 04/07/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 02:00 A 78 How Much I Feel Ambrosia 02:04 A 78 This Time I'm In It For Love Player 02:08 A 70 Ain't No Mountain High Enough (Shor Diana Ross 02:11 A 67 Happy Together Turtles 02:14 A 75 Breaking Up Is Hard To Do Neil Sedaka 02:16 A I.G.Y. -

Ukulelesongbook-20110710.Pdf

47. Me and Julio Down By The School Yard (Paul Table of Contents Simon) ... 77 48. Teenage Dirtbag (Wheatus) ... 79 1. Jambalaya (Hank Williams) ... 3 49. Teo Torriate (Brian May / Queen) ... 81 2. Horse With No Name (America) ... 4 50. Turning Japanese (The Vapors) ... 83 3. Elanor Rigby (The Beatles (Lenon/McCartney)) 51. Something Good (The Sound of Music ... 5 (Rogers/Hammerstein)) ... 85 4. Jamaica Farewell (Trad, Belafonte) ... 7 52. I Like Bananas (Becuase They Have No Bones) 5. Paperback Writer (The Beatles (Chris Yacich) ... 86 (Lenon/McCartney)) ... 8 53. Happy Talk (Rogers and Hammerstein) ... 87 6. Tom Dooley (Trad.) ... 9 54. Sweet Child O' Mine (Guns'N'Roses) ... 88 7. Brown Girl In The Ring (Trad Jamaican, Boney 55. Got My Mind Set on You (George Harrison) M) ... 10 ... 89 8. I Saw Her Standing There (Beatles) ... 11 56. Woyaya (We Are Going) (Osibisa) ... 90 9. Octopus' Garden (The Beatles 57. Sunny Afternoon (The Kinks) ... 91 (Lenon/McCartney)) ... 13 58. Peaches (Presidents of the United States) ... 10. With Or Without You (U2) ... 14 93 11. YMCA (Village People) ... 15 59. I Want A Banana (Tolchard Evans / Ralph 12. My Beloved Monster (Eels) ... 17 Butler) ... 94 13. Wimoweh ... 18 60. Short People (Randy Newman) ... 95 14. Midnight Special (Trad ) ... 19 61. Something Stupid (C. Carson Parks) ... 97 15. Love Me Do (Lenon/McCartney) ... 20 62. All You Need Is Love (Lenon/McCartney) ... 16. Down on the Corner (John Fogerty (Creedence 99 Clearwater Revival)) ... 21 63. Tomorrow (Strouse/Charnin) ... 101 17. Turn Turn Turn (Pete Seeger) ... 22 64. Walk Right In (Gus Cannon) .. -

032819.Log ********** 88.5 Fm Keom 03/28/19

032819.LOG ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 03/28/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 12:00 A 72 I'd Love You To Want Me Lobo 12:03 A 75 Evil Woman Electric Light Orchestra 12:06 A 77 Blue Bayou Linda Ronstadt 12:10 A Keep The Fire Burnin' REO Speedwagon 12:14 A 65 I Hear A Symphony Diana Ross & Supremes 12:16 A 74 The Show Must Go On Three Dog Night 12:19 A 82 Breaking Us In Two Joe Jackson 12:24 A 71 Brand New Key Melanie 12:26 A 91 Power Of Love-Love Power Luther Vandross 12:31 A 89 On Our Own Bobby Brown 12:36 A 74 Doctor's Orders Carol Douglas 12:39 A 96 Always Be My Baby Mariah Carey 12:46 A 78 (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 12:50 A 72 I'll Be Around Spinners ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 03/28/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 01:00 A 76 Evergreen Barbra Streisand 01:03 A 76 Nights Are Forever Without You England Dan & John Ford Coley 01:05 A 76 Welcome Back John Sebastian 01:08 A 83 Never Gonna Let You Go Sergio Mendes 01:12 A 66 We Can Work It Out Beatles Page 1 032819.LOG 01:16 A 74 Hollywood Swinging Kool & The Gang 01:19 A 84 If She Knew What She Wants Bangles 01:23 A 73 Danny's Song Anne Murray 01:26 A 72 You're So Vain Carly Simon 01:31 A 95 Run Around Blues Traveler 01:35 A 87 Who's That Girl Madonna 01:39 A 78 The Power Of Gold Dan Fogelberg 01:43 A 90 Love Will Lead You Back Taylor Dayne 01:46 A 79 Sara Fleetwood Mac 01:50 A 73 Loves Me Like A Rock Paul Simon 01:54 A 74 I'm Not In Love 10CC ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 03/28/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 02:00 A 70 The Letter Joe Cocker 02:04 A 76 Get Up And Boogie Silver Convention -

Top500 Final

35. NEIL YOUNG Heart Of Gold 36. PRINCE When Doves Cry 37. EAGLES Lyin’ Eyes 38. ARCHIES Sugar, Sugar 39. THE KNACK My Sharona 40. BEE GEES Stayin’ Alive 41. BOB DYLAN Like A Rolling Stone 42. AMERICA Sister Golden Hair 43. ALANNAH MYLES Black Velvet 44. FRANKI VALLI Grease 45. PAT BENATAR Hit Me With Your Best Shot 46. EMOTIONS Best Of My Love 47. KIM CARNES Bette Davis Eyes 48. LYNYRD SKYNYRD Sweet Home Alabama 49. STEPPENWOLF Born To Be Wild 50. ELTON JOHN PhiladelPhia Freedom 51. LOVERBOY Working For The Weekend 52. ROLLING STONES Honky Tonk Women 53. BILL HALEY & THE COMETS (We’re Gonna) Rock Around The Clock 54. GORDON LIGHTFOOT Sundown 55. BILLY JOEL It’s Still Rock And Roll To Me 56. MONKEES I’m A Believer 57. JONI MITCHELL HelP Me 58. DAVID BOWIE Modern Love 59. THREE DOG NIGHT Joy To The World 60. ANDY KIM Rock Me Gently 61. STEVIE WONDER Sir Duke 62. CYNDI LAUPER Girls Just Want To Have Fun 63. TURTLES HaPPy Together 64. TERRY JACKS Seasons In The Sun 65. ROLLING STONES Start Me UP 66. IRENE CARA Flashdance 67. OTIS REDDING Dock Of The Bay 68. KIM MITCHELL Patio Lanterns 69. WINGS Band On The Run 70. HUMAN LEAGUE Don’t You Want Me 71 . MICHAEL JACKSON Thriller 72. COREY HART Sunglasses At Night 73. BEATLES I Want To Hold Your Hand 74. GUESS WHO These Eyes 75. BON JOVI You Give Love A Bad Name 76. RIGHTEOUS BROTHERS You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling 77. -

February 5, 2018 Paul Simon Announces Homeward

FEBRUARY 5, 2018 PAUL SIMON ANNOUNCES HOMEWARD BOUND – THE FAREWELL TOUR Artist to stage ultimate concert performances in North America, UK and Europe, promising audiences an historic evening of career-spanning hits and timeless classics NEW YORK, February 5, 2018 – Legendary songwriter, recording artist and performer Paul Simon, will embark on his farewell concert tour on May 16 in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada at Rogers Arena. Homeward Bound – The Farewell Tour will encompass shows across North America, the United Kingdom and Europe, with Simon and his band bringing to the stage a stunning, career-spanning repertoire of timeless hits and classic songs which have permeated and influenced popular culture for generations. Tickets for Paul Simon’s Homeward Bound – The Farewell Tour will go on sale beginning February. The complete tour itinerary is listed below. Go to PaulSimon.com for ticketing information as it becomes available. According to Simon, the Homeward Bound tour is a fitting culmination of a performing career that began in the early 1960s and has coincided with his artistic journey as a songwriter and recording artist until the present day. He said of this farewell tour, “I’ve often wondered what it would feel like to reach the point where I'd consider bringing my performing career to a natural end. Now I know: it feels a little unsettling, a touch exhilarating and something of a relief. I love making music, my voice is still strong, and my band is a tight, extraordinary group of gifted musicians. I think about music constantly. I am very grateful for a fulfilling career and, of course, most of all to the audiences who heard something in my music that touched their hearts.” - more – Having created a distinctive and beloved body of work that includes 13 studio albums, plus five studio albums as half of Simon & Garfunkel, Paul Simon is the recipient of 16 Grammy Awards, three of which—Bridge over Troubled Water, Still Crazy after All These Years, and Graceland— were Album of the Year honorees. -

Sheet1 Page 1 3:00 AM Matchbox Twenty 1999 Prince

Sheet1 3:00 AM matchbox twenty 1999 Prince (Don't Fear) The Reaper Blue Oyster Cult (Everything I Do) I Do It For You [Long] Bryan Adams (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (Just Like) Starting Over [false end at 3:20] John Lennon (Keep Feeling) Fascination Human League (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (This Is) A Song For The Lonely Cher (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) [Yeah :00, voc :07 Beastie Boys (You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman Aretha Franklin 100 Years Five For Fighting 25 Or 6 To 4 [Edit] Chicago 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Paul Simon 867-5309/Jenny Tommy Tutone 99 Red Balloons [English Version] Nena A Whiter Shade Of Pale Procol Harum Absolutely (The Story Of A Girl) Nine Days Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Addicted To Love [Long] Robert Palmer Adia Sarah McLachlan Africa [Long] Toto Against All Odds (Take A Look At Me Now) Phil Collins Against The Wind [Long] Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band Ain't Nothin' 'bout You Brooks & Dunn Ain't Too Proud To Beg Temptations, The All Along The Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All Apologies [Album Version] Nirvana All For You [Full Band Version] Sister Hazel All I Wanna Do [Remix] Sheryl Crow All My Life Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville All My Love Led Zeppelin All Night Long (All Night) [Short] Lionel Richie All Out Of Love Air Supply All Over You Live All She Wants To Do Is Dance Don Henley All Star Smash Mouth All That She Wants Ace Of Base All The Small Things Blink-182 All Through The Night Cyndi Lauper All -

Schedule Quickprint TKRN-FM

Schedule QuickPrint TKRN-FM 12/31/2020 10A through 12/31/2020 2PM s: AirTime s: Runtime Schedule: Description 10:00:00a 00:00 Thursday, December 31, 2020 10A 10:00:00a 03:37 MY BEST FRIEND'S GIRL / CARS 10:03:37a 03:15 DOES ANYBODY REALLY KNOW WHAT TIME IT IS? / CHICAGO 10:06:52a 02:32 YOU ARE THE WOMAN / FIREFALL 10:09:24a 03:47 BROWN SUGAR / ROLLING STONES 10:13:11a 03:28 WE ARE FAMILY / SISTER SLEDGE 10:16:39a 04:46 TAKIN' CARE OF BUSINESS / BACHMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE 10:21:25a 03:55 YOUR SONG / ELTON JOHN 10:25:20a 03:03 LOVES ME LIKE A ROCK / PAUL SIMON 10:28:27a 03:30 STOP-SET 10:35:13a 03:36 ISN'T SHE LOVELY (EDIT) / STEVIE WONDER 10:38:49a 03:05 HI HI HI / PAUL MC CARTNEY & WINGS 10:41:54a 06:22 HOTEL CALIFORNIA / EAGLES 10:48:16a 04:32 MOONDANCE / VAN MORRISON 10:52:48a 03:30 STOP-SET 11:00:00a 00:00 Thursday, December 31, 2020 11A 11:00:00a 03:48 DON'T YOU WANT ME / HUMAN LEAGUE 11:03:48a 04:14 EVERYTIME YOU GO AWAY / PAUL YOUNG 11:08:02a 02:57 WAKE ME UP BEFORE YOU GO-GO / WHAM! 11:10:59a 04:42 IN YOUR EYES / PETER GABRIEL 11:15:41a 04:21 FAITHFULLY / JOURNEY 11:20:02a 04:03 YOU KEEP ME HANGIN' ON / KIM WILDE 11:24:05a 04:22 TOO MUCH TIME ON MY HANDS / STYX 11:28:31a 03:30 STOP-SET 11:35:15a 03:58 FOREVER YOUNG / ROD STEWART 11:39:13a 04:29 SARA (SINGLE) / FLEETWOOD MAC 11:43:42a 04:44 WITH OR WITHOUT YOU / U2 11:48:26a 04:17 I JUST CALLED TO SAY I LOVE YOU / STEVIE WONDER 11:52:43a 03:30 STOP-SET 12:00:00p 00:00 Thursday, December 31, 2020 12P 12:00:00p 03:28 SWEET DREAMS (ARE MADE OF THIS) / EURHYTHMICS 12:03:28p 04:11 VOICES -

The Songs YOU Voted As Your Favorites! (Special Expanded Edition)

The Songs YOU Voted As Your Favorites! (Special Expanded Edition) Title Artist Year 1 Hey Jude Beatles 1968 2 Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 3 American Pie Don McLean 1972 4 I Want To Hold Your Hand Beatles 1964 5 In The Still Of The Nite Five Satins 1956 6 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 7 Light My Fire Doors 1967 8 Rag Doll Four Seasons 1964 9 Good Vibrations Beach Boys 1966 10 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon and Garfunkel 1970 11 Ain't No Mountain High Enough Diana Ross 1970 12 MacArthur Park Richard Harris 1968 13 Let It Be Beatles 1970 14 Bohemian Rhapsody Queen 76/92 15 God Only Knows Beach Boys 1966 16 Cherish Association 1966 17 Be My Baby Ronettes 1963 18 She Loves You Beatles 1964 19 Hotel California Eagles 1977 20 My Girl Temptations 1965 21 Like A Rolling Stone Bob Dylan 1965 22 A Day In The Life Beatles 1967 23 Downtown Petula Clark 1965 24 Since I Don't Have You Skyliners 1959 25 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 26 California Dreamin' Mamas and the Papas 1966 27 Wichita Lineman Glen Campbell 1968 28 Taxi Harry Chapin 1972 29 Waterloo Sunset Kinks 1967 30 Can't Find The Time Orpheus 1969 31 Layla Derek & the Dominos 1972 32 You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' Righteous Brothers 1965 33 Suspicious Minds Elvis Presley 1969 34 Will You Love Me Tomorrow Shirelles 1961 35 Brandy (You're A Fine Girl) Looking Glass 1972 36 The Rain The Park & Other Things Cowsills 1967 37 Can't Help Falling In Love Elvis Presley 1962 38 Crystal Blue Persuasion Tommy James and the Shondells 1969 39 Aquarius Let The Sunshine In 5th Dimension