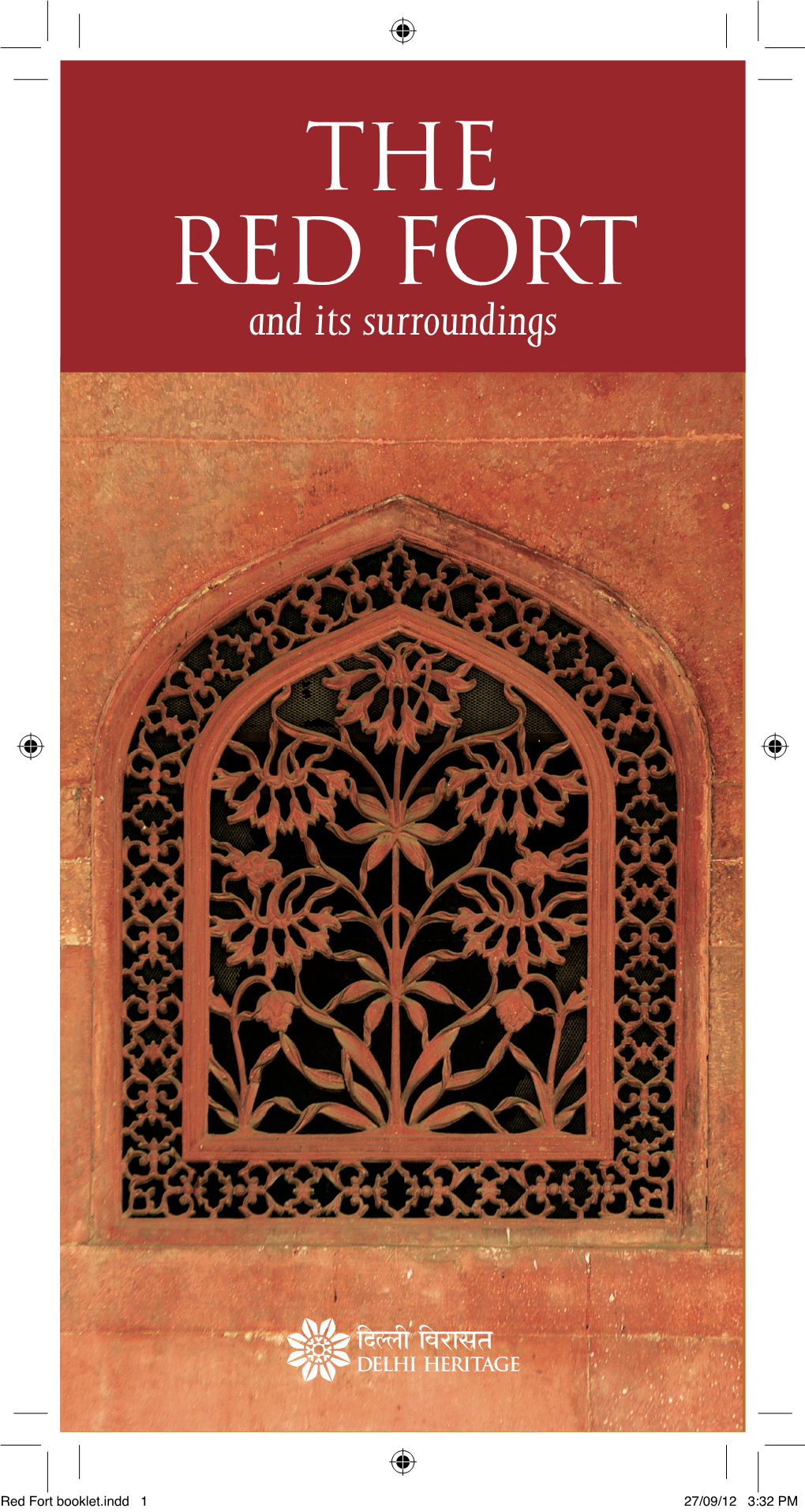

Red Fort Booklet.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Horizon Tours

New Horizon Tours Presents INTOXICATING, INCREDIBLE INDIA MARCH 14 -MARCH 26, 2020 (LAX) Mar. 14, SAT: PARTICIPANTS from Los Angeles (LAX) board on Emirates air at 4.35PM Mar. 15, SUN: LAX PARTICIPANTS ARRIVE IN DUBAI AND CONNECT FLIGHT TO MUMBAI / Washington (IAD) participants depart at 11.10 AM Mar. 16, MON: ARRIVE MUMBAI Different times- LAX passengers arrive at 2.15AM (immediate occupancy of rooms- rooms reserved from Mar. 15). IAD passengers arrive at 2.00 PM- separate arrival transfers for each in Mumbai. Arrive in Mumbai, a cluster of seven islands derives its name from Mumba devi, the patron goddess of Koli fisher folk, the oldest habitants. Meeting assistance and transfer to Hotel. Rest of the day is free. Evening welcome dinner at roof top restaurant at Hotel near airport. HOTEL.OBEROI TRIDENT (Breakfast & Dinner for LAX passengers, Dinner only for IAD participants). Mar. 17, TUE: MUMBAI - CITY TOUR – BL Breakfast at Hotel. This morning embark on city tour of Mumbai visiting the British built Gateway of India, Bombay's landmark constructed in 1927 to commemorate Emperor George V's visit, the first State, ever to see India by a reigning monarch. Followed by a drive through the city to see the unique architecture, Mumbai University, Victoria Terminus, Marine Drive, Chowpatty Beach. Next stop at Hanging Gardens (now known as Sir K.P. Mehta Gardens), where the old English art of topiary is practiced. Continue to the Dhobi Ghat, an open-air laundry where washmen physically clean and iron hundreds of items of clothing, delivering them the next day. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Sacralizing the City: the Begums of Bhopal and Their Mosques

DOI: 10.15415/cs.2014.12007 Sacralizing the City: The Begums of Bhopal and their Mosques Jyoti Pandey Sharma Abstract Princely building ventures in post 1857 colonial India included, among others, construction of religious buildings, even as their patrons enthusiastically pursued the colonial modernist agenda. This paper examines the architectural patronage of the Bhopal Begums, the women rulers of Bhopal State, who raised three grand mosques in their capital, Bhopal, in the 19th and early 20th century. As Bhopal marched on the road to progress under the Begums’ patronage, the mosques heralded the presence of Islam in the city in the post uprising scenario where both Muslims and mosques were subjected to retribution for fomenting the 1857 insurrection. Bhopal’s mosques were not only sacred sites for the devout but also impacted the public realm of the city. Their construction drew significantly on the Mughal architectural archetype, thus affording the Begums an opportunity to assert themselves, via their mosques, as legitimate inheritors of the Mughal legacy, including taking charge of the latter’s legacy of stewardship of Islam. Today, the Bhopal mosques constitute an integral part of the city’s built heritage corpus. It is worth underscoring that they are not only important symbols of the Muslim faith but also markers of their patrons’ endeavour to position themselves at the forefront in the complex political and cultural scenario of post uprising colonial India. Keywords Bhopal Begums; Modernity; Mosques; Mughal legacy; Uprising INTRODUCTION The architecture of British ruled Indian Subcontinent has been a popular subject of scholarship from the colonial perspective with the architectural patronage of princely India also receiving due academic attention1. -

Download List of Famous Mosques in India

Famous Palaces in India Revised on 16-May-2018 ` Railways RRB Study Material (Download PDF) Mosque Location Jama Masjid (Bhilai) Bhilai, Chhattisgarh Jama Masjid Delhi Quwwatul Islam Masjid Delhi Moti Masjid (Red Fort) Delhi Quwwatul Islam Masjid Delhi Jamali Kamali Mosque and Tomb Delhi Sidi Sayyid Mosque Ahmedabad, Gujarat Sidi Bashir Mosque Ahmedabad, Gujarat Jamia Masjid Srinagar, Jammu & Kashmir Hazratbal Shrine Srinagar, Jammu & Kashmir Download Fathers of various fields in Science and Technology PDF Taj-ul-Masajid Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh Haji Ali Dargah Mumbai, Maharashtra Adhai Din Ka Jhonpra Ajmer, Rajasthan Ajmer Sharif Dargah Ajmer, Rajasthan Makkah Masjid Hyderabad, Telangana Gyanvapi Mosque Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh Moti Masjid (Agra Fort) Agra, Uttar Pradesh Nagina Masjid Agra, Uttar Pradesh (Gem Mosque or the Jewel Mosque) Jama Mosque (Fatehpur Sikri) Agra, Uttar Pradesh IBPS PO Free Mock Test 2 / 6 Railways RRB Study Material (Download PDF) Mosque Location Tomb of Salim Chishti Fatehpur Sikri, Uttar Pradesh Bara Imambara Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh Chota Imambara Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh Beemapally Mosque Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala Cheraman Juma Mosque Thrissur, Kerala Other Places of Interest Tombs/ Mausoleums Location Taj Mahal Agra, Uttar Pradesh Tomb of Mariam-uz-Zamani Sikandra, Agra, Uttar Pradesh Tomb of Adam Khan Qutub Minar, Mehrauli, Delhi Bibi Ka Maqbara (Taj of Deccan) Aurangabad, Maharashtra *Humayun’s Tomb Delhi Download Modern India History Notes PDF Tomb of I'timād-ud-Daulah Agra, Uttar Pradesh (Baby Taj) Tomb of -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and w h itephotographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World'sUMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8824569 The architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq McKibben, William Jeffrey, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by McKibben, William Jeflfrey. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

Sales Tax Bar Association

WARD-WISE LIST OF MAIN MARKETS & LOCALITIES OF DELHI Checked and corrected upto 30/11/2016 Ward Main Markets & Localities No. 1. Blocks A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, K, L, M, N, Connaught Place, Palika Bazar, and Parking. 2. I.P.Estate, Kasturba Gandhi Marg, Ansal Bhawan, Hindustan Times House, Barakhamba Road, South Eastern side of Sikandara Road to Connaught Place, Tolstoy Marg, New Delhi House, Scindia House, Eastern side of Janpath, National Stadium, Nehru Sports Club of India, Pragati Maidan. 3. Western side of Janpath, Sansad Marg, Windser Place, (Western Side) Regal Building, Mohan Singh Place, Baba Kharak Singh Marg, Emporium Complex, Bhagat Singh Road, Panchkuian Road, (Southern Side) Ashok Road. 4. Bazar Paharganj, Desh Bandhu Gupta Road (Southern side), Panchkuian Road (Northern side), Aram Bagh, Chelmsford Road, Chuna Mandi, Krishna Market, Amrit Kaur Market, Rattan Market, Nehru Bazar. 5. Nabi Karim Market, Qutub Road (Part), Idgah Road Market (Southern side) 6. Qutab Road (Part), Ram Nagar, Aram Nagar, Desh Bandhu Gupta Marg (Northern side part), Multani Dhanda. 7. Kamla Market, Gandhi Market, Deen Dayal Upadhyay Marg, Bengali Market, Barakhamba Road (Northern side), Kotla Ferozshah, I.P. Stadium 8. Netaji Subhash Marg Shops, Darya Ganj, Ansari Road Market. 9. Asaf Ali Road, Churiwalan Southern side, Pahari Bhojla, Chitle Qabar, Main Market from Delhi Gate Bazar. 10. Netaji Subhash Marg (Western side), Bazar Delhi Gate, Bazar Chitli Qabar, Bazar Daryaganj, Urdu Bazar, Meena Bazar, Esplande Road, Southern side of Chandni Chowk from Netaji Subhash Marg to Dariba Kalan. 11. Mela Ram Market, Mela Ram House, Makki Market, Jain Paper Market, Jama Masjid Motor Market, Chota Chippiwara, Churiwalan Chitla Gate, Charhat. -

The Last Mughal Transcript

The Last Mughal Transcript Date: Monday, 7 July 2008 - 12:00AM THE LAST MUGHAL William Dalrymple I have just flown in from Delhi, which today is a city of about 15 million people, if you count the various suburbs on the edge that have sprung up over the last few years. In contrast, if had you visited Delhi 150 years ago this month, in July 1858, you would have found that this city, which was the cultural capital of North India for so many centuries, had been left completely deserted and empty. Not a single soul lived in the walled city of Delhi in July 1858. The reason for this was that in the previous year, 1857, Delhi became the centre of the largest anti-colonial revolt to take place anywhere in the world, against any European power, at any point in the 19th Century. That uprising is known in this country as 'the Indian Mutiny', is known in India as 'the First War of Independence'. Neither the Indian Mutiny nor the First War of Independence are particularly useful titles. What happened in Delhi was much more than a mutiny of soldiers, because it encompassed almost all the discontented classes of the Gangetic Plains, but was not quite a national war of independence either, as it had rather particular aims of restoring the Mughal Dynasty back to power. Whether we call it an 'uprising' or 'rising', by it the two institutions which had formed North Indian history for the previous 300 years came to an abrupt and complete halt. In human affairs, dates rarely regulate the ebb and flow or real lives. -

Photo Tour of Golden Triangle with Pushkare Fair in 2018

PHOTO TOUR OF GOLDEN TRIANGLE WITH PUSHKARE FAIR IN 2018 11 Nov 2018 Arrival Delhi Traditional welcome on arrival and transfer to hotel for overnight stay. (Only one arrival transfer is included in our tour package, supplement cost of USD 20 will be applicable if any guest will arrive in different flight) Note – Please note that check in time of hotel is 12 Noon 12 Nov 2018 Delhi After breakfast first photo opportunity at Humayun Tomb. Humayun's tomb is the tomb of the Mughal Emperor Humayun in Delhi, India. The tomb was commissioned by Humayun's first wife Bega Begum in 1569-70, and designed by Mirak Mirza Ghiyas, a Persian architect chosen by Bega Begum Later we will take you to the Qutab Minar which is the tallest brick minarety in the world, and the second tallest minar in India after Fateh Burj at Mohali. Qutub Minar, along with the ancient and medieval monuments surrounding it, form the Qutb Complex, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Made of red sandstone and marble, Qutub Minar is a 73-meter (240 feet) tall tapering tower with a diameter measuring 14.32 meters (47 feet) at the base and 2.75 meters (9 feet) at the peak. Inside the tower, a circular staircase with 379 steps leads to the top Afternoon (After Lunch) we will take you to the photo tour of Old Delhi. In the 17th century, the Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan, made his capital in the area that broadly covers present-day Old Delhi—he called it Shahjahanabad. -

Book of Islamic Arts Overview There Is Much Diversity Within Islamic Culture

Book of Islamic Arts Overview There is much diversity within Islamic culture. During this unit, students will learn about several significant forms of Islamic art (mosque architecture, geometric/arabesque design, and calligraphy) by completing a children’s book that is missing important information or images. The book is divided up into 5 class sessions with an optional 6th session to wrap up missing sections or create a cover. Through the exploration, students will learn that Islamic art around the world can include many different concepts, and they will apply new knowledge through note-taking, graphic organizers, drawing, calligraphy, and optional mosaic portions of the book. When finished, each student will have a completed book that reviews the arts covered in the unit and celebrates the diversity of Muslim culture around the world. Grade 5 Subject Visual Arts Essential Standards • 5.V.2.2 - Use ideas and imagery from the global environment as sources for creating art. • 5.V.3.3 - Create art using the processes of drawing, painting, weaving, printing, stitchery, collage, mixed media, sculpture, ceramics, and current technology. • 5.CX.1 - Understand the global, historical, societal, and cultural contexts of the visual arts. Essential Questions • How do pictures help to tell a story? • How do Muslim artists reflect their local culture through the arts? • What can we learn about Islamic culture from the diversity of Islamic arts? • Why is it important to learn about cultures other than our own? Materials • Copies of the children’s book for each student (attached). The student book is 10 pages long and can be printed on regular copy paper, or on stronger paper like Bristol or cardstock if the teacher intends to use paint. -

Street the Heat

Food & Drink FINAL.qxd 7/16/2009 5:20 PM Page 36 Shahjahanabad coolers Street the heat Feeling a bit parched in purani Dilli, Sonal Shahquenches her thirst at various local institutions. Photography Taveeshi Singh Murarilal Inderjit Sharma Bikaner Sweet Shop The crowd outside Murari’s Compared to some surround- lassi, dahi, milk and paneer outlet ing vendors, this namkeen in Kinari Bazaar is relentless. shop is a newbie, having been Established about 60 years ago, established only 27 years ago. the dairy stall uses two of Delhi’s That certainly doesn’t stop Food & Drink classic “Sultan” machines to passers-by from availing of the churn creamy – but not excessive- shop’s convenient location in ly thick – lassi in kullars and steel Dariba, just out of the sun of glasses. Some of the area’s mer- Chandni Chowk. A bucket of chants bring their own silver cups ice holds bottles of kaju milk, to be filled. A squirt of kewra is pista milk and badam milk. added and the glass is topped with 255 Dariba Kalan, off Chandni a thin, creamy-crisp slab of malai Chowk (2328-1971). before serving. A namkeen ver- m Chandni Chowk. Rs 20. sion is also available. 2178 Kinari Bazaar (2327-1464). m Chandni Chowk. Rs 20. Sheher-e-sharbat Though the line of sharbats is manu- factured in the dusty industrial Amritsari Lassi Wala area of Lawrence Road and despite The thickest lassi we’ve found in the fact that most of the ingredients old Delhi is available at this well- listed involve preservatives, known neon-yellow shop. -

FROM the INSIDE ARCHITECTURE in RELATION to the F E M a L E FORM in the TIME of the INDIAN MUGHAL EMPIRE Itinerary

Days 5-8 - Exploration of the city of Jaipur with focus on Moghul architecture, such as the HAWA MAHAL located within days in Jaipur the Royal Palace. The original intent of the lattice design was to allow royal ladies to observe everyday life and festivals celebrated in the street below without being seen. 4 FROM THE INSIDE ARCHITECTURE IN RELATION TO THE F e m a l e FORM IN THE TIME OF THE INDIAN MUGHAL EMPIRE itinerary b e g i n* new delhi jaipur agra If you wander through the hot and crowded streets of windows, called jharokas, that acted as screens be- Jaipur, meander through the grand palace gates, and tween these private quarters and the exterior world. On days in New Delhi find yourself in the very back of the palace complex, the other hand, women held power in these spaces, and you will be confronted by a unique, five story struc- molded these environments to their wills. Their quar- ture of magnificent splendor. It is the Hawa Mahal, ters were organized according to the power they welded and it has 953 lattice covered windows carved out of over the men who housed them. Thus, architecture be- *first and last days are pink stone. Designed in the shape of Lord Krishna’s came the threshold that framed these women’s worlds. reserved3 for travel crown, it was built for one purpose only. To allow royal ladies to observe everyday life and festivals We seek to explore the way the built environment celebrated in the street below without being seen.