Organismal Futurisms in Brown Sound and Queer Luminosity: Getting Into Gressman’S Cyborgian Skin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIPAW Wall Texts

3rd Venice International Performance Art Week, 2016 Ouch – Pain and Performance A screening programme curated by Live Art Development Agency, London “I see pain as an inevitable byproduct of interesting performance.” Dominic Johnson According to Wikipedia ‘pain’ is an “unpleasant feeling often caused by intense or damaging stimuli…(it) motivates the individual to withdraw from damaging situations and to avoid similar experiences in the future.” But for many artists and audiences the opposite is just as true, and pain within the context of performance is a challenging, exhilarating and profound experience. Ouch is a collection of documentation and artists’ films looking at pain and performance. The works are not necessarily performances about pain, but in some way involve or invoke pain in their making or reading or experience - both the pain artists cause themselves within the course of their work, whether intentional or not, and the experiences of audiences as they are invited to inflict pain on artists or are subjected to pain and discomfort themselves. The selected works feature eminent and ground breaking artists from around the world whose practices address provocative issues including the lived experiences of illness, the aging female body, cosmetic surgery, addiction, embodied public protest, animalistic impulses, blood letting, staged fights, acts of self harm and flagellation, and what can happen when you invite audiences to be complicit in performance actions. Ouch featured artists: Marina Abramovic, Ron Athey, Marcel.Li Antunez Roca, Franko B, Wafaa Bilal, Rocio Boliver, Cassils, Bob Flanagan, Regina Jose Galindo, jamie lewis hadley, Nicola Hunter & Ernst Fischer, Oleg Kulik, Martin O’Brien, Kira O’Reilly, ORLAN, Petr Pavlensky. -

FAÇADE: ZONE A: Religion/Family

CHECKLIST for Participant Inc. February 14-April 4, 2021 Curated by Amelia Jones Archival and research assistance by Ana Briz, David Frantz, Hannah Grossman, Dominic Johnson, Maddie Phinney *** UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED ALL ITEMS ARE FROM THE RON ATHEY ARCHIVE*** ***NOTE: photographs are credited where authorship is known*** FAÇADE: Rear projection of “Esoterrorist” text by Genesis P’Orridge, edited and video mapped as a word virus, as projected in the final scene of Ron Athey’s Acephalous Monster, “Cephalophore: Entering the Forest,” 2018-19. Video graphics work by Studio Ouroboros, Berlin. ZONE A: Religion/Family This section of the exhibition features a key work expanding on Ron Athey’s family and religious upbringing as a would-be Pentacostal minister: his 2002 live multimedia performance installation Joyce, which is named after Athey’s mother. It also includes elements from Athey’s archive relating to Joyce—including two costumes from the live performance—and his life within and beyond his fundamentalist origin family (such as unpublished writings from his period of recovery in the 1980s, and the numerous flyers advertising fundamentalist revivals he attended). The section is organized around materials that evoke the mix of religiosity and dysfunctional (sexualized and incestuous) family dynamics Athey experienced as a child and wrote about in some of his autobiographical writings that are included in the catalogue, including Mary Magdalene Footwashing Set (1996), which was included in a group show at Western Project in Los Angeles in 2006 and in the Invisible Exports Gallery “Displaced Person” show in 2012, a former gallery just around the corner from Participant Inc.’s location. -

An Examination of Minimalist Tendencies in Two Early Works by Terry Riley Ann Glazer Niren Indiana University Southeast First I

An Examination of Minimalist Tendencies in Two Early Works by Terry Riley Ann Glazer Niren Indiana University Southeast First International Conference on Music and Minimalism University of Wales, Bangor Friday, August 31, 2007 Minimalism is perhaps one of the most misunderstood musical movements of the latter half of the twentieth century. Even among musicians, there is considerable disagreement as to the meaning of the term “minimalism” and which pieces should be categorized under this broad heading.1 Furthermore, minimalism is often referenced using negative terminology such as “trance music” or “stuck-needle music.” Yet, its impact cannot be overstated, influencing both composers of art and rock music. Within the original group of minimalists, consisting of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass2, the latter two have received considerable attention and many of their works are widely known, even to non-musicians. However, Terry Riley is one of the most innovative members of this auspicious group, and yet, he has not always received the appropriate recognition that he deserves. Most musicians familiar with twentieth century music realize that he is the composer of In C, a work widely considered to be the piece that actually launched the minimalist movement. But is it really his first minimalist work? Two pieces that Riley wrote early in his career as a graduate student at Berkeley warrant closer attention. Riley composed his String Quartet in 1960 and the String Trio the following year. These two works are virtually unknown today, but they exhibit some interesting minimalist tendencies and indeed foreshadow some of Riley’s later developments. -

AMRC Journal Volume 21

American Music Research Center Jo urnal Volume 21 • 2012 Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder The American Music Research Center Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Dominic Ray, O. P. (1913 –1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music Eric Hansen, Editorial Assistant Editorial Board C. F. Alan Cass Portia Maultsby Susan Cook Tom C. Owens Robert Fink Katherine Preston William Kearns Laurie Sampsel Karl Kroeger Ann Sears Paul Laird Jessica Sternfeld Victoria Lindsay Levine Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Kip Lornell Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25 per issue ($28 outside the U.S. and Canada) Please address all inquiries to Eric Hansen, AMRC, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. Email: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISBN 1058-3572 © 2012 by Board of Regents of the University of Colorado Information for Authors The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing arti - cles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and proposals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (exclud - ing notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, Uni ver - sity of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. Each separate article should be submitted in two double-spaced, single-sided hard copies. -

City Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by City Research Online City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2019). The Historiography of Minimal Music and the Challenge of Andriessen to Narratives of American Exceptionalism (1). In: Dodd, R. (Ed.), Writing to Louis Andriessen: Commentaries on life in music. (pp. 83-101). Eindhoven, the Netherlands: Lecturis. ISBN 9789462263079 This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/22291/ Link to published version: Copyright and reuse: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Historiography of Minimal Music and the Challenge of Andriessen to Narratives of American Exceptionalism (1) Ian Pace Introduction Assumptions of over-arching unity amongst composers and compositions solely on the basis of common nationality/region are extremely problematic in the modern era, with great facility of travel and communications. Arguments can be made on the bases of shared cultural experiences, including language and education, but these need to be tested rather than simply assumed. Yet there is an extensive tradition in particular of histories of music from the United States which assume such music constitutes a body of work separable from other concurrent music, or at least will benefit from such isolation, because of its supposed unique properties. -

Chapter Three Minimal Music

72 Chapter Three Minimal music This chapter begins with a brief outline of minimal music in the United States, Europe and Australia. Focusing on composers and stylistic characteristics of their music, plus aspects of minimal music pertinent to this study, it helps the reader situate the compositions, composers and events referred to throughout the thesis. The chapter then outlines reasons for engaging students aged 9 to 18 years in composing activities drawn from projects with minimalist characteristics, reasons often related to compositional or historical aspects of minimal music since the late 1960s. A number of these reasons are educational, concerned with minimalism as an accessible teaching resource that draws on students’ current musical knowledge and offers a bridge from which to explore musics of other cultures and other contemporary art musics. Other reasons are concerned with the performance capabilities of students, with the opportunity to introduce students to a contemporary aesthetic, to different structural possibilities and collaboration and subject integration opportunities. There is also an educational need for a study investigating student composing activities to focus on these activities in relation to contemporary art music. There are social reasons for engaging students in minimalist projects concerned with introducing students to contemporary arts practice through ‘the new tonality’, involving students with a contemporary music which is often controversial, and engaging students with minimalism at a time of particular activity and expansion in the United States and in Australia. 3.1 Minimalism Minimalism is an aesthetic found across a number of different art forms – architecture, dance, visual art, theatre, design and music - and at the beginning of the twenty-first century, it is still strongly influential on many contemporary artists. -

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: a Question of the Body and Its Reflections As Gesture

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: A Question of the Body and its Reflections as Gesture. ...material action is painting that has spread beyond the picture surface. The human body, a laid table or a room becomes the picture surface. Time is added to the dimension of the body and space. - "Material Action Manifesto," Otto Muhl, 1964 VIS 2 Winter 2017 When: Thursday: 6:30 p.m. to 8:20p.m. Where: PCYNH 106 Professor: Ricardo Dominguez Email: [email protected] Office Hour: Thursday. 11:00 a.m. to Noon. Room: VAF Studio 551 (2nd Fl. Visual Art Facility) The body-as-gesture has a long history as a site of aesthetic experimentation and reflection. Art-as-gesture has almost always been anchored to the body, the body in time, the body in space and the leftovers of the body This class will focus on the history of these bodies-as-gestures in performance art. An additional objective for the course will focus on the question of documentation in order to understand its relationship to performance as an active frame/framing of reflection. We will look at modernist, contemporary and post-contemporary, contemporary work by Chris Burden, Ulay and Abramovic, Allen Kaprow, Vito Acconci, Coco Fusco, Faith Wilding, Anne Hamilton, William Pope L., Tehching Hsieh, Revered Billy, Nao Bustamante, Ana Mendieta, Cindy Sherman, Adrian Piper, Sophie Calle, Ron Athey, Patty Chang, James Luna, and the work of many other body artists/performance artists. Students will develop 1 performance action a week, for 5 weeks, for a total of 5 gestures/actions (during the first part of the class), individually or in collaboration with other students. -

(Un)Disciplined Bodies: Ascetic Transformation in Performance Art

(Un)Disciplined Bodies: Ascetic Transformation in Performance Art Tatiana A. Koroleva A Thesis In the Department Of Humanities Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Humanities) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April, 2014 © Tatiana A. Koroleva, 2014 ABSTRACT (Un)Disciplined Bodies: Ascetic Transformation in Performance Art Tatiana A. Koroleva, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2014 This dissertation investigates different modalities of self-transformation enacted in ritualistic performance art by the examination of the work of three contemporary performance artists – Marina Abramović, Linda Montano and Ron Athey. Drawing on theoretical models of ritual, in particular the model of ascetic ritual developed in the works of Gavin Flood and Richard Valantasis, Georges Bataille’s theory of sacrifice, concepts of wounded healing by Laurence J. Kirmayer and Jess Groesbeck, and recent studies of ascetic self-injury in psychiatry and psychoanalysis, I argue that ritualistic performance provides a useful model of the therapy of the body that undermines rigid models of the individual self. Ritualistic performance employs a variety of methods of re-patterning of the dominant standard of individuality and formation of alternative model of the body associated with the ascetic self. In view of significance of the transcendence of the body in the work of these artists I employ a theory of “transformation” to reflect upon performative methodology developed in the artworks of Abramović, Montano, and Athey. iii AKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the support and generosity I have received from my academic advisors: Mark Sussman, Tim Clark, and Shaman Hatley. Their work and contributions have been invaluable to the research and writing for this dissertation. -

ON PAIN in PERFORMANCE ART by Jareh Das

BEARING WITNESS: ON PAIN IN PERFORMANCE ART by Jareh Das Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Geography Royal Holloway, University of London, 2016 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Jareh Das hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 19th December 2016 2 Acknowledgments This thesis is the result of the generosity of the artists, Ron Athey, Martin O’Brien and Ulay. They, who all continue to create genre-bending and deeply moving works that allow for multiple readings of the body as it continues to evolve alongside all sort of cultural, technological, social, and political shifts. I have numerous friends, family (Das and Krys), colleagues and acQuaintances to thank all at different stages but here, I will mention a few who have been instrumental to this process – Deniz Unal, Joanna Reynolds, Adia Sowho, Emmanuel Balogun, Cleo Joseph, Amanprit Sandhu, Irina Stark, Denise Kwan, Kirsty Buchanan, Samantha Astic, Samantha Sweeting, Ali McGlip, Nina Valjarevic, Sara Naim, Grace Morgan Pardo, Ana Francisca Amaral, Anna Maria Pinaka, Kim Cowans, Rebecca Bligh, Sebastian Kozak and Sabrina Grimwood. They helped me through the most difficult parts of this thesis, and some were instrumental in the editing of this text. (Jo, Emmanuel, Anna Maria, Grace, Deniz, Kirsty and Ali) and even encouraged my initial application (Sabrina and Rebecca). I must add that without the supervision and support of Professor Harriet Hawkins, this thesis would not have been completed. -

Fluxus: the Is Gnificant Role of Female Artists Megan Butcher

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College Summer 7-2018 Fluxus: The iS gnificant Role of Female Artists Megan Butcher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Contemporary Art Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Butcher, Megan, "Fluxus: The iS gnificant Role of Female Artists" (2018). Honors College Theses. 178. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/178 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract The Fluxus movement of the 1960s and early 1970s laid the groundwork for future female artists and performance art as a medium. However, throughout my research, I have found that while there is evidence that female artists played an important role in this art movement, they were often not written about or credited for their contributions. Literature on the subject is also quite limited. Many books and journals only mention the more prominent female artists of Fluxus, leaving the lesser-known female artists difficult to research. The lack of scholarly discussion has led to the inaccurate documentation of the development of Fluxus art and how it influenced later movements. Additionally, the absence of research suggests that female artists’ work was less important and, consequently, keeps their efforts and achievements unknown. It can be demonstrated that works of art created by little-known female artists later influenced more prominent artists, but the original works have gone unacknowledged. -

FIGURE 7.1. Demonstration/Performance by The

07 Chapter 7.qxd 12/8/2006 2:46 PM Page 192 FIGURE 7.1. Demonstration/performance by the Art Workers Coalition at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1971, in support of AWC cofounder Hans Haacke, whose exhibition was canceled by the museum’s director over his artwork Shapolsky et al., Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971. Photographer unknown. L 07 Chapter 7.qxd 12/8/2006 2:46 PM Page 193 7. Artists’ Collectives Mostly in New York, 1975–2000 ALAN W. MOORE The question of collectivism in recent art is a broad one. Artists’ groups are an intimate part of postmodern artistic production in the visual arts, and their presence informs a wide spectrum of issues including modes of artistic practice, the exhibition and sales system, publicity and criticism, even the styles and subjects of art making. Groups of all kinds, collectives, collaborations, and organizations cut across the landscape of the art world. These groups are largely autonomous organizations of artistic labor that, along with the markets and institutions of capital expressed through galleries and museums, comprise and direct art. The presence of artistic collectives is not primarily a question of ideology; it is the expression of artistic labor itself. The practical requirements of artistic production and exhibition, as well as the education that usually precedes active careers, continuously involves some or a lot of collective work. The worldwide rise in the number of self- identiWed artist collectives in recent years reXects a change in patterns of artistic labor, both in the general economy (that is, artistic work for com- mercial media) and within the special economy of contemporary art. -

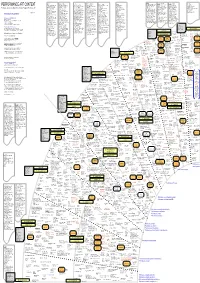

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles