Dot Com Unity: Exploring the Sense of Community in the Af Gang, Idles’ Online Fan Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ST/LIFE/PAGE<LIF-004>

C4 life happenings | THE STRAITS TIMES | FRIDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2020 | Eddino Abdul Hadi Music Correspondent recommends SINGAPORE COMMUNITY RADIO Picks Online music platform Singapore Community Radio has gone through a major revamp and now champions an even wider range of Singapore creatives. New programmes include bi-weekly show The Potluck Music Club, which features guests such as design collective Tell Your Children and carpentry studio Roger&Sons; High Tide, which focuses on Mandarin indie music; and 10 Tracks, where artists, producers and personalities each share 10 songs that define him or her. Besides its regular roster of DJs such as DJ Itch and Kim Wong, the platform will invite musicians such as ambient artist Kin Leonn and electronic artist The Analog Girl to curate and present their mix of music. Other new offerings include The Same Page, a podcast by local bookstore The Moon; and The Squelch Zinecast, a podcast that spotlights the local zine community. Tomorrow and next Saturday, the platform will celebrate the fifth anniversary of local record store The Analog Vault with live-streamed performances by home-grown acts such as .gif, Intriguant, Hanging Up The Moon and Rah. WHERE: Various online platforms including Twitch (www.twitch.tv/sgcommunityradio) and Spotify (spoti.fi/3cJIz1w) The people behind online music platform Singapore Community Radio: (from far left) creative director Darren Tan, managing editor Daniel Peters and producer Hwee En Tan. MUSIC AT MONUMENTS Museum – in conjunction with the This new series features four Chongyang Festival. The Chinese home-grown acts from various holiday to celebrate senior citizens genres whose festive-themed falls on Oct 25 this year. -

This Ain't a Scene, It's a Buzzer Race.Pdf

This Ain’t a Scene, It’s a Buzzer Race Sadboys are temporary. Sad trumpets are forever. Written by Brian Luong Tossups: 1. This band’s extensive and impressive merchandise catalogue can be attributed to guitarist Nick Steinhardt’s side occupation as a graphic designer. A live EP following this band’s sophomore studio album was titled Live on BBC Radio 1 and featured vocals from Jordan Dreyer of La Dispute. It’s not Red Hot Chili Peppers, but this band’s distinct asterisk-shaped logo was meant to evoke converging road markings leading to a sunset, and was first used in promotional artwork for the band’s second album, with that album’s initials “PTSBBAM” arranged in the negative spaces of the logo. This band’s 2016 single “Palm Dreams” was described by their frontman as a song about his inability to ask his mother about why she moved to California after she passed. The album from which that single is taken, as a whole, deals with themes of frontman Jeremy Bolm grieving the loss of his mother due to cancer. For 10 points, give the name of this Los Angeles-based post-hardcore band, which you may know from the albums Parting the Sea Between Brightness and Me and Stage Four. ANSWER: Touché Amoré 2. This website once hosted a stand-up and sketch comedy tour titled All Comics Are Bastards. This website’s sister site was also responsible for the creation and management of the Twitter account of Ace Watkins, whose bio reads, “The only Gamer running for President of the United States”. -

Download De Pdf Van Mania 371

www.platomania.nl 9 oktober 2020 - nr. 371 Het blad van/voor muziekliefhebbers NO RISK DISC Idles MANIA major muscle • independent spirit proudly presents Action Bronson 23.10 “My next album is only for dolphins” aldus Action Bronson op zijn vorige album. De rapper, chef, TV-bekendheid, schrijver en acteur hield zich aan zijn woord. Het nieuwe album “Only For Dolphins” geeft een tour door het creatieve brein van Bronson. Matt Berninger Peter Gabriel 16.10 16.10 ‘Live in Athens 1987’ is de tweede ‘Serpentine Prison’ is het uit een reeks van vier liveplaten solodebuut van GRAMMY- van Peter Gabriel die de komende winnaar en The National frontman maanden uitkomen. Deze show Matt Berninger. Het album bevat was de climax van de ‘This Way diep persoonlijke tracks, gegoten Up’ tour en werd opgenomen in in de karakteristieke sound een Grieks openluchttheater. Dit NO van de veel geprezen producer album vescheen nooit eerder op Booker T. Jones. vinyl. RISK Underworld 09.10 DISC Deze CD box is een verzameling IDLES van het ‘Drift Series 1’ experiment Ultra Mono van Underworld. De box bevat naast alle Drift Series 1 films en (Partisan/PIAS) een 50 pagina’s tellend boek ook LP coloured ltd., LP Deluxe, LP, CD een CD met daarop het nooit Als een van de spannendste Britse gitaarbandjes eerder uitgebrachte heeft IDLES na de doorbraak twee jaar terug ‘RicksDubbedOutDriftExperience’ wel flink wat waar te maken. War zet meteen (live in Amsterdam). de toon met een vuige baslijn en machinale drums. Seconden later slingert zanger Joe Talbot zelfspot en sarcasme. -

Fore- Verbatim Inside

VOLUME 53, ISSUE 4 MONDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2019 WWW.UCSDGUARDIAN.ORG SAN DIEGO PHOTOCONCERT REVIEW:TEASE !"#$%&'()%*+',-.."/%+' RAVEENA GOES HERE 0++1%+'2#"#%3%4#')4' 5-#6'7)3%.%++4%++'8."4' The statement is in regards to the 1.9 million dollars in funding that the city is providing to combat homelessness !/#P=P=$%#"$%E -./00(*,%&', The San Diego City Council unanimously accepted the City of San Diego Community Action Plan on Homelessness which aims to prevent homelessness and provide PHOTO BY NAME HERE /GUARDIAN housing service with $1.9 million funding over the next 10 years on CAPTION PREVIEWING Oct. 14, 2019. "Raveena reminded UC San Diego Family Weekend kicks of with Homecoming soccer wins. // Photo by Lauren McGee THEus ARTICLE all to PAIREDdo what WITH Prior to the City Council’s weTHE needPHOTO the TEASE. most: FOR voting, Father Joe’s Villages, a EXAMPLE IF THE PHOTO local organization that provides Take a moment. services such as food, sheltering WERE OF A BABY YOU RESEARCH Breathe. Soften and transitioning programs for WOULD SAY “BABIES SUCK! ;52@'5-#%A'B-#$'#$%'@%"#$'): 'C'D%+%"&=$'21EF%=#+ homeless people in San Diego, yourTHEY AREedges. WEAK Love. AND !"##$%&'()#*$###!""#$%!&'()'*"('+%&#, made a statement about the Heal." Community Action Plan, showing ,5:4203D##1-I5##FA&E, page 8 ecent allegations have come to light should treat their test subjects humanely and approval and support. that UC San Diego poisoned six with respect. “If this plan is to be successful, J-72-335##92..2-J,03 animal research subjects in October “This violation is particularly heinous a critical component will be the R2018. -

Nightshift Magazine

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 261 April Oxford’s Music Magazine 2017 The August List “The idea of disappearing or living in absolute isolation photo:Ian Wallman is a rejection of the world and I find that fascinating.” Oxford’s first couple of country on hermits and the power of drones. Also in this issue: Introducing LOWWS STORNOWAY bow out plus Oxford music news, reviews, previews, and seven pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshiftmag.co.uk Barnabas Church; The Pitt Rivers Museum and St Aldates Tavern. The Folk Weekend line-up also features sets from Leverett; The Melrose Quartet; Ange Hardy; Jim Moray; Jackie Oates & Megan Henwood; John Spiers; Dan Walsh; Dipper Malkin; Jimmy Aldridge & Sid Goldsmith and The Emily Askew Band, while the local folk contingent is represented by Coldharbour; Edward Pope, White IDRIS ELBA is the latest star name added to the line-up for Truck Horse Whisperers and Shivelight, Festival. The star of The Wire and Luther will play a DJ set at the among others. As well as concerts festival over the weekend of the 21st-23rd July at Hill Farm in there will be the traditional round Steventon. The event, headlined by The Libertines, Franz Ferdinand of ceilidhs, dance displays, Morris KT TUNSTALL, JON BODEN and The Vaccines, is close to selling out in advance with no general dancers and workshops, while and ELIZA CARTHY head weekend camping tickets left. -

Tracks of Our Year

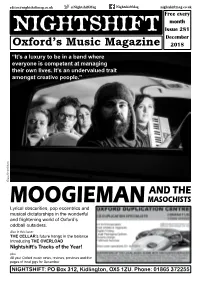

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 281 December Oxford’s Music Magazine 2018 “It’s a luxury to be in a band where everyone is competent at managing their own lives. It’s an undervalued trait amongst creative people.” GlassHertzzPhoto AND THE MOOGIEMAN MASOCHISTS Lyrical obscurities, pop eccentrics and musical dictatorships in the wonderful and frightening world of Oxford’s oddball outsiders. Also in this issue: THE CELLAR’s future hangs in the balance Introducing THE OVERLOAD Nightshift’s Tracks of the Year! plus All your Oxford music news, reviews, previews and five pages of local gigs for December NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshiftmag.co.uk NICK COPE releases his sixth album this month. The former Candyskins frontman turned children’s songwriter releases `Have You Heard About Hugh?’ on the 8th December and features an array of local musicians, including folk singer Jackie Oates. Talking about his latest THE FUTURE OF THE CELLAR HUNG IN THE BALANCE set of family-friendly songs, Nick as Nightshift went to press. said: “The title track is a huge live As of the 20th November the crowdfunding campaign has raised over favourite about a poor hedgehog £55,000 – 69% of the total £80,000 needed to complete the construction stranded on the A32 with his mum work required on the building to allow it to regain its full capacity. A willing him on from the other side of safety inspection in July ruled the venue’s fire escape, which has stood the road; it’s edge of the seat stuff! for 40 years, was 30cm too narrow; consequently its capacity was cut to KYLIE MINOGUE is the first There are also songs about gender just 60, making the venue financially unviable. -

Sfreeweekl Ysince | April

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | APRIL | APRIL CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE TK TK. By TK TK THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | APRIL | VOLUME NUMBER IN THIS ISSUE T R - homeandothersmanthefrontlines ofJoeMantegna’steenagegarage @ ofcoronavirustransmissionthe bandtheApocryphals censusgoeson 35 EarlyWarningsRescheduled PTB 10 Dukmasova|HousingA concertsandotherupdatedlistings EC S K KH leakedvideochatrevealsthecity’s C LRH MEP M landlordsareconcernedoverstaff TDKR “decimation”andtheopticsof CEBW “stepping”ontenants AEJL SWMD L G 12 Reid|NewsTheAmerican DIBJ MS SignLanguageinterpreterforthe THEATER EAS N L governorisinthespotlightbuthe 19 DanceDancersfi gureouthowto G D AH CITYLIFE L CSC -J 03 SightseeingThedeathsof wantsustoknowmoreaboutthe createinisolation CE BN B nearlyathousandsailorsatGreat ChicagoHearingSociety’sservices L C MDLC M LakesNavalTrainingStation C J F SF J FILM H IH C MJ inholdlessonsforthe 22 SmallScreenThedigital M K S K COVIDpandemic televisionplatformOTVisthriving 35 GossipWolfMavisStaples N DL JL 23 MoviesofnoteNeverRarely dropsabenefi tsingletohelp MMA M-K JRN JN M SometimesAlwaysisaslowmoving Chicagoseniorssurvivethe O M S C S fi lmbuttheseyoungwomenwill pandemicMukqsembarkson ---------------------------------------------------------------- staywithyoulonga erthefi lm aweeklyseriesofliverecorded D D J D endsThere’sSomethinginthe experimentalEPsandmore D AC W Wateriscrucialviewingforanyone SMCJ G MP C whocaresaboutthelastingripple OPINION YD eff ectsofenvironmentalneglect 36 SavageLoveDanSavageoff -

Daily Eastern News: February 03, 2020

Eastern Illinois University The Keep February 2020 2-3-2020 Daily Eastern News: February 03, 2020 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2020_feb Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: February 03, 2020" (2020). February. 1. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2020_feb/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the 2020 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in February by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHECKING IN 0 NEW YEAR'S RESOLUTIONS BLOWOUT WIN We talked to Eastern students and asked them how their new year's 'The Eastern women's basketball team won resolutions were going as we are now one month into the year 2020. big over Austin Peay on Saturday 76-47. The Panthers are now 6-4 in OVC play. PAGE 8 t I AILY �-ASTERN EWS "TELL THE TRUTH AND DON'T BE AFRAID" Garoppolo, 49ers fall short in Super Bowl MIAMI GARDENS, Fla. (AP) - Patrick Mahomes led Kansas City to three touchdowns in the final 6:13, and the Chiefs overcame a double-digit deficit for the third postseason , . game in a row to beat the San Francisco 49ers 31-20 Sunday in the Super Bowl. The Chiefs (15-4) were playing in the cham pionship game for the first time since 1970, when they won their only previous NFL title. Coach Andy Reid earned his 222nd career victo ry, and his first in a Super Bowl. The Chiefs trailed 20-10 and faced a third and 15 when Mahomes threw deep to a wide open Tyreek Hill for 44 yards. -

Punks, Die Keine Sein Wollen

# 2020/41 dschungel https://jungle.world/artikel/2020/41/punks-die-keine-sein-wollen Das neue Album der Idles Punks, die keine sein wollen Von Konstantin Nowotny Die britischen Idles sind die »woke« Version einer Rockband. Mal ehrlich: Was ist eigentlich noch Punk? Ein bisschen antibürgerlicher Habitus, eine Frisur wie Sascha Lobo – oder 1977 und sonst nichts? Jahrelang stritten sich Bands und Fans um das begehrte Label, aber heutige Gruppen wollen damit nichts mehr zu tun haben. »Zum letzten Mal: Wir sind keine verdammte Punkband«, insistierte Joe Talbot, der Sänger der britischen Band Idles, bei einer Show in Manchester im traditionsreichen »The Ritz«, das heutzutage kapitalistisch korrekt »O2 Ritz« heißt. Das war 2018, Idles hatten gerade ihr zweites Album »Joy as an Act of Resistance« veröffentlicht, das ähnlich erfolgreich war wie das Debüt »Brutalism« von 2017. Die 2009 gegründete Band spielte ausverkaufte Konzerte auf Welttourneen, eröffnete für die Foo Fighters, war später bei den Brit Awards 2019 für den Titel »Best Breakthrough Act« nominiert. Ziemlich unpunkig, das Ganze, oder? Was Idles schon immer besonders gemacht hat, ist, dass sie Schicksale nicht ausschließlich auf individuelle Ursachen zurückführen und sich damit von der ewig gleichen introspektiven, unpolitischen Befindlichkeitslyrik abheben. Die jüngst erschienene Platte »Ultra Mono« ist anders. Zum Glück, möchte man sagen, denn beide Vorgängeralben haben ihren Ursprung zu weiten Teilen in persönliche Tragödien Talbots. Der Veröffentlichung von »Brutalism« ging der Tod seiner Mutter voraus, die er seit seinem 16. Lebensjahr pflegte. Sie starb, während die Band das Album schrieb. Er verewigte sie in Form einer Fotografie auf dem Cover. -

School Magazine

Editor's Note Dear Readers, Thank You for reading the first issue of the 2018 school magazine, it’s been a long time coming and the school magazine team have been working really hard on writing their articles and getting them out to you, hope you enjoy! The editorial team, Kate Heggie, Rosie Maguire, Douglas Simpson and Dylan Brotherston. Contents: Sport The Rugby Season World Record Attempt At Haddington Rugby Club Girls Fitness and Breakfast Club Horoscope Music MGK vs Eminem Joy As An Act Of Resistance Film And Television The Incredibles 2 The Princess Bride Shaun Of The Dead Retrospective I Love Rahul But He Shouldn’t Have Won God's Not Dead In Loving Memory Food, Drinks And Baking East Lothian Food And Drink Recommendations Very Late Halloween Recipes For all The Goths Out There (Gregor) Knox Sport The Rugby Season Knox u18s have had a rather easy start to the season, with two development games which were automatic wins due to other teams not having enough players. We turned up to play competitive and so did our components, Linlithgow Academy and Lasswade High School. Although we had won before the game had begun by the end of the games our team were the deserved winners. Linlithgow Academy(Match one) We travelled about an hour to get to Linlithgow, the “hype” tunes were blaring and someone put George Ezra on, on in Bruce’s famous clio. We arrived at the ground with “Take Me Home Country Road” blaring out the speaker with the window down trying be intimidating but this did absolutely not work. -

Vol LII Issue 1

Volume LII Issue 1 September 12, 2018 page 2 the paper september 12, 2018 NYS Govenor, pg. 3 Kaepernick, pg. 9 Jurassic Park, pg. 15 F & L, pg. 21-22 Earwax, pg. 23 the paper “What school supply are you?” c/o Office of Student Involvement Editors-in-Chief Fordham University Colleen “Fine Point Sharpie” Burns Bronx, NY 10458 Claire “A Condom” Nunez [email protected] Executive Editor http://fupaper.blog/ Michael Jack “A DVD of Ice Age 3” O’Brien News Editors the paper is Fordham’s journal of news, analysis, comment and review. Students from all Christian “Stapler” Decker years and disciplines get together biweekly to produce a printed version of the paper using Andrew “Silly Bandz” Millman Adobe InDesign and publish an online version using Wordpress. Photos are “borrowed” from Opinions Editors Internet sites and edited in Photoshop. Open meetings are held Tuesdays at 9:00 PM in McGin- Jack “Giant Ass Paper Cutter” Archambault ley 2nd. Articles can be submitted via e-mail to [email protected]. Submissions from Hillary “Teeny Tiny Scissors” Bosch students are always considered and usually published. Our staff is more than willing to help new writers develop their own unique voices and figure out how to most effectively convey their Arts Editors thoughts and ideas. We do not assign topics to our writers either. The process is as follows: Meredith “Kooky Pen” McLaughlin have an idea for an article, send us an e-mail or come to our meetings to pitch your idea, write Annie “Pencil Pouch” Muscat the article, work on edits with us, and then get published! We are happy to work with anyone Earwax Editor who is interested, so if you have any questions, comments or concerns please shoot us an e- Marty “Mattress Protector” Gatto mail or come to our next meeting. -

So Much More Than You’Re Expecting

We deliver so much more than you’re expecting. At UPMC Magee-Womens Hospital, we deliver so much for parents and their babies. By creating a personalized journey for every expectant mom, we help women with uncomplicated pregnancies as well as those who need more complex care. From genetic testing to our internationally recognized expertise in comprehensive maternal-fetal medicine for high-risk pregnancies, Magee delivers so much more than you’re expecting. To learn more, visit UPMC.com/MageeWeDeliver. 8983_upmc_magee_wd_general_er_10.5x12.25_a.indd 1 10/5/18 3:59 PM CONTENTS: From the Editors The only local voice for A rebuilding year: news, arts, and culture. December 19, 2018 We deliver Editors-in-Chief: brick by brick Brian Graham & Adam Welsh ver the past few years we’ve felt some Managing Editor: 2018 Year in Review – 5 Nick Warren negativity as the Year in Review issue ap- proached. That burning desire to finally so much more Copy Editor: Snuffing out the dumpster fire of O Matt Swanseger disillusionment en route to improvement say good-bye to the year that was and start again. than you’re expecting. Contributing Editors: Looking back on our covers you’ll find the looming Ben Speggen Gem City Playbook: It’s All in the specter of death putting an end to 2014, a garbage Jim Wertz dump in 2015, and in 2016 we needed a martini Contributors: Execution – 10 just to process it all. Those years seem like child’s At UPMC Magee-Womens Hospital, we deliver so much for parents and their babies.