The Law of Real Property in England and the United States: Some Comparisons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk

Federal Trade Commission ftc.gov The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk Buying a home can be exciting. It also can be somewhat daunting, even if you’ve done it before. You will deal with mortgage options, credit reports, loan applications, contracts, points, appraisals, change orders, inspections, warranties, walk-throughs, settlement sheets, escrow accounts, recording fees, insurance, taxes...the list goes on. No doubt you will hear and see words and terms you’ve never heard before. Just what do they all mean? The Federal Trade Commission, the agency that promotes competition and protects consumers, has prepared this glossary to help you better understand the terms commonly used in the real estate and mortgage marketplace. A Annual Percentage Rate (APR): The cost of Appraisal: A professional analysis used a loan or other financing as an annual rate. to estimate the value of the property. This The APR includes the interest rate, points, includes examples of sales of similar prop- broker fees and certain other credit charges erties. a borrower is required to pay. Appraiser: A professional who conducts an Annuity: An amount paid yearly or at other analysis of the property, including examples regular intervals, often at a guaranteed of sales of similar properties in order to de- minimum amount. Also, a type of insurance velop an estimate of the value of the prop- policy in which the policy holder makes erty. The analysis is called an “appraisal.” payments for a fixed period or until a stated age, and then receives annuity payments Appreciation: An increase in the market from the insurance company. -

Guidance Note

Guidance note The Crown Estate – Escheat All general enquiries regarding escheat should be Burges Salmon LLP represents The Crown Estate in relation addressed in the first instance to property which may be subject to escheat to the Crown by email to escheat.queries@ under common law. This note is a brief explanation of this burges-salmon.com or by complex and arcane aspect of our legal system intended post to Escheats, Burges for the guidance of persons who may be affected by or Salmon LLP, One Glass Wharf, interested in such property. It is not a complete exposition Bristol BS2 0ZX. of the law nor a substitute for legal advice. Basic principles English land law has, since feudal times, vested in the joint tenants upon a trust determine the bankrupt’s interest and been based on a system of tenure. A of land. the trustee’s obligations and liabilities freeholder is not an absolute owner but • Freehold property held subject to a trust. with effect from the date of disclaimer. a“tenant in fee simple” holding, in most The property may then become subject Properties which may be subject to escheat cases, directly from the Sovereign, as lord to escheat. within England, Wales and Northern Ireland paramount of all the land in the realm. fall to be dealt with by Burges Salmon LLP • Disclaimer by liquidator Whenever a “tenancy in fee simple”comes on behalf of The Crown Estate, except for In the case of a company which is being to an end, for whatever reason, the land in properties within the County of Cornwall wound up in England and Wales, the liquidator may, by giving the prescribed question may become subject to escheat or the County Palatine of Lancaster. -

Overreaching: Beneficiaries in Occupation

-The Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 188) TRANSFER OF LAND OVERREACHING: BENEFICIARIES IN OCCUPATION Laid before Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 19 December 1989 LONDON HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE L4.90 net 61 The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commissioners are- The Right Honourable Lord Justice Beldam, Chairman Mr Trevor M. Aldridge Mr Jack Beatson Mr Richard Buxton, Q.C. Professor Brenda Hoggett, Q.C. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Collon and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WClN 2BQ. OVERREACHING BENEFICIARIES IN OCCUPATION CONTENTS Pa ragraph Page PART I: INTRODUCTION 1.1 1 Background and scope 1.1 1 Recommendations 1.7 2 Structure of this report 1.8 2 PART 11: THE PRESENT LAW 2.1 3 Introductory 2.1 3 Equitable interests 2.3 3 Overreaching 2.9 4 Mortgagees 2.14 5 Personal representatives 2.16 6 Bare trustees 2.17 6 Safeguard for beneficiaries 2.18 7 Registered land 2.2 1 7 Registration of beneficiary’s interests 2.25 8 Beneficiary in occupation: summary 2.28 9 PART 111: NEED FOR REFORM 3.1 10 Change of circumstances 3.1 10 Protecting occupation of property 3.4 10 Bare trusts 3.10 12 PART IV REFORM PROPOSALS 4.1 13 Principal recommendation 4.1 13 Beneficiaries 4.4 13 (a) Interests 4.5 13 (b) Capacity 4.8 14 (c) Occupation 4.11 14 (d) Consent 4.15 15 Conveyances by mortgagees 4.20 16 Conveyances by personal representatives 4.22 16 Conveyances under court order 4.23 17 Conveyancing procedure 4.24 17 Second recommendation: bare trusts 4.27 18 Transitional provisions 4.28 18 Application to the Crown 4.30 18 PART V: SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS 5.1 19 APPENDIX A Draft Law of Property (Overreaching) Bill with Explanatory Notes 21 APPENDIX B: Individuals and organisations who com- mented on Working Paper No. -

Chapter 6 Summary Ownership of Real Property

Chapter 6 Summary Ownership of Real Property California Real Estate Principles Estate in land - degree of ownership one holds in the land. Feudal system - all land was once owned by the king/government; Allodial System (USA) - although the government detains some rights, individuals own property without proprietary control of government. Freehold estate - the estate lasts at least a lifetime; leasehold estate - renting or leasing. Types of freehold: • Fee Simple (Fee Simple Absolute) - Owns the bundle of rights – unlimited duration; inheritable. • Fee Simple Defeasible is based on an occurrence of a specified event – conditions. • Fee Tail - Property inherited by a monarch is illegal in the United States. • Life Estate: Voluntary Life Estates or "Conventional Life Estates." o Estate in Reversion • A life estate that is deeded to a life tenant - incomplete bundle of rights during lifetime. • A reversion estate that is retained by the grantor. After death of life tenant, grantor has complete bundle of rights. o Estate in remainder: differs from the above because the remainder estate is given to a third party who is known as the remainderman. After death of life tenant, the remainderman has complete bundle of rights. o Pur Autre Vie (estate in reversion/estate in remainder) - life tenant has the incomplete bundle of rights until a third party dies. o Involuntary Life Estates are legal life estates or marital right. It is not possible to sell the property without the consent of the partner, or to own property in one name only. o Dower - a wife's interest in the husband's property; Curtesy - a husband's interest in a wife's property; Homestead - protection against unsecured debts for the party who did not sign for the loan. -

Confronting Remote Ownership Problems with Ecological Law

CONFRONTING REMOTE OWNERSHIP PROBLEMS WITH ECOLOGICAL LAW Geoffrey Garver* ABSTRACT ThomasBerry’s powerfulappeal foramutually enhancing human- Earthrelationshipfaces many challengesdue to theecological crisis that is co-identifiedwith dominant growth-insistenteconomic,political, andlegal systemsacrossthe world. Thedomains of environmental history, ecological restoration, and eco-culturalrestoration, as well as studies by Elinor Ostrom and othersofsustainableuse of commonpool resources,provide insightsonthe necessary conditions foramutually enhancing human-Earth relationship. Atheme commontothesedomains is theneed forintimate knowledgeofand connectiontoplace that requiresalong-standing commitment of people to theecosystems that sustainthem.Remoteprivate ownership—oftenbylarge and politically powerful multinational corporations financed by investorsseeking thehighest possiblereturns and lacking knowledgeorinterestinthe places and people they harm—is deeplyengrained in theglobal economic system.The historical rootsof remote ownership and controlgoback to territorial extensification associated with thesharpriseofcolonialismand long-distancetradeinthe earlymodernera.Yet remote owners’and investors’ detachment from place poses an enormous challenge in thequest foramutually enhancing human-Earthrelationship. ThisEssaypresents an analysis of how contemporary environmental lawundergirds theremoteownershipproblem and of how limits-insistentecological lawcouldprovide solutions. ABSTRACT..................................................................................................425 -

Present Legal Estates in Fee Simple

CHAPTER 3 Present Legal Estates in Fee Simple A. THE ENGLISH LAW T THE beginning of the thirteenth century, when the royal courts of justice were acquiring effective A control of the development of private law, the possible forms of action and their limits were uncertain. It seemed then that a new form of action could be de vised to fit any need which might arise. In the course of that century the courts set themselves to limiting the possible forms of action to a definite list, defining with certainty the scope of permitted actions, and so refusing relief upon states of fact which did not fall within the fixed limits of permitted forms of action. This process, of course, operated to fix and limit the classes of private rights protected by law.101 A parallel process went on with respect to interests in land. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, when alienation of land was becoming possible, it seemed that any sort of interest which ingenuity could devise might be created by apt terms in the transfer creating the interest. Perhaps the form of the gift could create interests of any specified duration, with peculiar rules for descent, with special rights not ordinarily in cident to ownership, or deprived of some of the ordinary incidents of ownership. As in the case of the forms of action, the courts set themselves to limiting the possible interests in land to a definite list, defining with certainty 1o1 Maitland, FoRMS OF ACTION AT CoMMON LAW 51-52 (reprint 1941). 37 38 PERPETUITIES AND OTHER RESTRAINTS the incidents of permitted interests, and refusing to en force provisions of a gift which would add to or subtract from the fixed incidents of the type of interest conveyed. -

The Law of Property

THE LAW OF PROPERTY SUPPLEMENTAL READINGS Class 14 Professor Robert T. Farley, JD/LLM PROPERTY KEYED TO DUKEMINIER/KRIER/ALEXANDER/SCHILL SIXTH EDITION Calvin Massey Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law The Emanuel Lo,w Outlines Series /\SPEN PUBLISHERS 76 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 http://lawschool.aspenpublishers.com 29 CHAPTER 2 FREEHOLD ESTATES ChapterScope ------------------- This chapter examines the freehold estates - the various ways in which people can own land. Here are the most important points in this chapter. ■ The various freehold estates are contemporary adaptations of medieval ideas about land owner ship. Past notions, even when no longer relevant, persist but ought not do so. ■ Estates are rights to present possession of land. An estate in land is a legal construct, something apart fromthe land itself. Estates are abstract, figments of our legal imagination; land is real and tangible. An estate can, and does, travel from person to person, or change its nature or duration, while the landjust sits there, spinning calmly through space. ■ The fee simple absolute is the most important estate. The feesimple absolute is what we normally think of when we think of ownership. A fee simple absolute is capable of enduringforever though, obviously, no single owner of it will last so long. ■ Other estates endure for a lesser time than forever; they are either capable of expiring sooner or will definitely do so. ■ The life estate is a right to possession forthe life of some living person, usually (but not always) the owner of the life estate. It is sure to expire because none of us lives forever. -

Get a Glossary of Terms Used in the Title Industry

GLOSSARY A Abstract Plant – A geographically arranged abstract plant, currently kept to date, that is adequate for use in insuring titles, so as to provide for the safety and protection of the policyholders. An abstract plant as further defined in Rule P-12 and as further provided for in the Insurance Code, Chapter 2501.003 and Chapter 2502, must include an abstract plant for each county in which a title insurance agent or direct operation maintains an office. Abstract of Title - A compilation of all the recorded documents relating to a parcel of land. Usually kept by the land owner and used as the basis for an attorney as to the condition of title. Still in use in some states, and in some areas of Texas, but mostly replaced by issuance of title insurance. Abstract of Judgment – A lien created by a statutory filing of a court judgment in the real property records. This lien, commonly referred to as an AJ (in Texas), attaches to all non- exempt real property of the person or entity that the judgment was against. Acceleration Clause (in a mortgage) – Specifies conditions under which the lender may advance the time when the entire debt which is secured by the mortgage becomes due. For example, most mortgages contain provisions that the note shall become due immediately upon the sale of the securing land without the lender's consent or upon failure of the landowner to pay an installment when due. Access – The right to enter and leave a tract of land from a public way. Can include the right to enter and leave over the lands of another. -

Article1. Land Law Article2. Land Ownership Arlicle 3. Unified

LAND CODE OF THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN The present Code regulates land relations and it is directed at the rational use and protection of land, recreation of fertility of the soil, maintenance and improvement of the natural environment and for equal development ofall forms ofeconomic activity in Tajikistan. Chapter 1. BASIC PROVISIONS Article 1. Land law Land relations in the Republic of Tajikistan are regulated by this Code and other Land Laws issued on the basisofthis Code. Issues related to the ownership and use of mountains, forests and water resources, to use and protection of the flora and fauna, protection of the environment is regulated by the current legislation of the Republic ofthe Republic ofTajikistan. Article2. Land ownership Land in the Republic of Tajikistan is an exclusive ownership of the state. The state guarantees its effective use in the interests of its citizens. Certiorari oflands, which belonged to the ancestors, is banned. Arlicle 3. Unified national resources In accordance with the purpose they serve, all national land resources of the Republic of Tajikistan are divided into the following categories: 1. Farming lands, 2. Populated lands (cities, towns, and villages), 3. Land used for industrial, transport, communications, defense and other purposes, 4. Conservation land, land ofhistoric and cultural value, land used for health-improvement and recreation purposes, 5. Lands ofnational wood reserves, 6. Lands ofnational water reserves, 7. State land reserves. The category ofland is stated in the following documents: a) In the state land cadastre; b) In the land use register; 238 c) In the decisions ofexecutive bodies about land allotment; d) In title deeds to land use and tillage. -

UNDERSTANDING INDEFEASIBILITY UNDER the VICTORIAN TRANSFER of LAND ACT by BERNARD O'brien*

UNDERSTANDING INDEFEASIBILITY UNDER THE VICTORIAN TRANSFER OF LAND ACT By BERNARD O'BRIEN* INTRODUCTION The central concept in Torrens system legislation is the principle of indefeasibility. It is commonly thought that once a title is recorded on the register, not only is the title created by the act of registration, but upon registration the statute will guarantee the validity of that title and confer upon it an immunity from any attack. Whilst it seems to be universally acknowledged that indefeasibility will result from the registration of title, controversy nonetheless exists as to when indefeasibility will attach to a registered title. The line of battle is drawn between those who favour the view of immediate indefeasibility and those who prefer the concept of deferred indefeasibility. It is dubious whether the various protagonists in this debate can be all grouped behind such simple labels. For instance, the deferred indefeasibility camp in turn divides according to two basically different approaches. There are those who rest their case on the basis that the registration of a void instrument cannot confer an indefeasible title in favour of the registrant even when that person is a bona fide purchaser for value.1 Alternatively, there are those who place paramount importance on s.43 of the Transfer of Land Act 1958 as being fundamental to the statutory scheme of indefeasibility.2 That section can be briefly described as providing that when a transferee of a registered proprietor deals with the registered proprietor he shall be relieved of the requirements of notice. The proponents of this view argue that this provision implies that indefeasibility only attaches to those titles which have been registered by a person who has acquired his title and entered the transaction on the faith of the register. -

REAL ESTATE LAW LESSON 1 OWNERSHIP RIGHTS (IN PROPERTY) Real Estate Law Outline LESSON 1 Pg

REAL ESTATE LAW LESSON 1 OWNERSHIP RIGHTS (IN PROPERTY) Real Estate Law Outline LESSON 1 Pg Ownership Rights (In Property) 3 Real vs Personal Property 5 . Personal Property 5 . Real Property 6 . Components of Real Property 6 . Subsurface Rights 6 . Air Rights 6 . Improvements 7 . Fixtures 7 The Four Tests of Intention 7 Manner of Attachment 7 Adaptation of the Object 8 Existence of an Agreement 8 Relationships of the Parties 8 Ownership of Plants and Trees 9 Severance 9 Water Rights 9 Appurtenances 10 Interest in Land 11 Estates in Land 11 Allodial System 11 Kinds of Estates 12 Freehold Estates 12 Fee Simple Absolute 12 Defeasible Fee 13 Fee Simple Determinable 13 Fee Simple Subject to Condition Subsequent 14 Fee Simple Subject to Condition Precedent 14 Fee Simple Subject to an Executory Limitation 15 Fee Tail 15 Life Estates 16 Legal Life Estates 17 Homestead Protection 17 Non-Freehold Estates 18 Estates for Years 19 Periodic Estate 19 Estates at Will 19 Estate at Sufferance 19 Common Law and Statutory Law 19 Copyright by Tony Portararo REV. 08-2014 1 REAL ESTATE LAW LESSON 1 OWNERSHIP RIGHTS (IN PROPERTY) Types of Ownership 20 Sole Ownership (An Estate in Severalty) 20 Partnerships 21 General Partnerships 21 Limited Partnerships 21 Joint Ventures 22 Syndications 22 Corporations 22 Concurrent Ownership 23 Tenants in Common 23 Joint Tenancy 24 Tenancy by the Entirety 25 Community Property 26 Trusts 26 Real Estate Investment Trusts 27 Intervivos and Testamentary Trusts 27 Land Trust 27 TEST ONE 29 TEST TWO (ANNOTATED) 39 Copyright by Tony Portararo REV. -

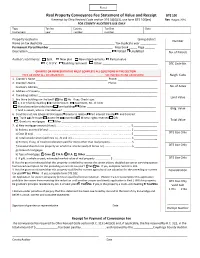

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt DTE 100 If exempt by Ohio Revised Code section 319.54(G)(3), use form DTE 100(ex) Rev 1/14 FOR COUNTY AUDITOR’S USE ONLY Type Tax list County Tax Dist Date Instrument year number number Property located in ____________________________________________________________ taxing district Number Name on tax duplicate ____________________________________________ Tax duplicate year __________ Permanent Parcel Number _______________________________________ Map book _____ Page ______ Description ___________________________________________________ Platted Unplatted No. of Parcels Auditor’s comments: Split New plat New improvements Partial value C.A.U.V. Building removed Other __________________________________ DTE Code No. GRANTEE OR REPRESENTATIVE MUST COMPLETE ALL QUESTIONS IN THIS SECTION TYPE OR PRINT ALL INFORMATION SEE INSTRUCTIONS ON REVERSE Neigh. Code 1. Grantor’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ 2. Grantee’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ Grantee’s Address__________________________________________________________________________________ No. of Acres 3. Address of Property ________________________________________________________________________________ 4. Tax billing address _________________________________________________________________________________ Land Value 5. Are there buildings on the land? Yes No If yes, Check type: 1, 2 or 3 family dwelling Condominium