Sadie) Ross Aitken, M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOOKING at TELEVISION -.:: Radio Times Archive

10 RMHO TIMES, ISSUE DATED JULY 23, 1937 THE WORLD WE LISTEN IN LISTENERS' LETTERS LOOKING AT TELEVISION (Continued from previous page) S. John Woods discvisses die tech• feeling of actuality is an absolutely fundamental Something for a Change part of television. MAY some of the splendid pianists we hear nique of television and contrasts it Intimacy and actuality, then, are two funda• be asked to play some of the works that are with that of the cinema mentals. A third, just as important, is person• never played ? I instance: Mendelssohn's ality. On the stage we have the living actor Concerto in D minor ; the Rondo Brillante before us, and conversely the actor has a living The Editor does not necessarily agree with by the same composer ; Schumann's Concerto audience before him and can gauge its reception the opinions expressed by his contributors in A minor ; Moszkowski's in E major, and of his acting. In television we have a similar many others. sense of having the actor before us, but for him It is quite true that you cannot have too VERY week some 250 million people visit it is more difficult; instead of having an audi• the cinema. Every year 750 million pounds much of a good thing but, as there are other E ence which he can reduce to laughter or tears, good things, why cannot we hear them played are invested in the production of films. Cinemas there is a forbidding, grey camera and a battery hold from 500 to 3,000 spectators and there by these experts ? One hears the announce• of hot lights. -

Discography Section 13: L (PDF)

1 DORA LABETTE (1898 – 1984). Soprano with string quartette Recorded London, December 1924 A-1494 The bonnie banks of Loch Loman’ (sic) (Lady John Scott; trad) Col D-1517, A-1495 A-1495 Comin’ thro the rye (Robert Burns; Robert Brenner) Col D-1517 Recorded London, Tuesday, 21st. February 1928 WA-6993-2 The bonnie banks of Loch Loman’ (Lady John Scott; trad) Col D-1517 WA-6994-1/2/3 Comin’ thro the rye (Robert Burns; Robert Brenner) Col rejected Recorded London, Sunday, 1st. September 1929 WA-6994-5 Comin’ thro the rye (Robert Burns; Robert Brenner) Col D-1517 NOTE: Other records by this artist are of no Scots interest. JAMES LACEY Vocal with piano Recorded West Hampstead, July 1940 M-925 Hame o' mine (Mackenzie Murdoch) Bel 2426, BL-2426 M-926 Mother Machree (Rida J.Young: Chauncey Olcott; Ernest R. Ball) Bel 2428, BL-2428 M-927 Macushla! (Josephine V. Rowe; Dermot MacMurrough) Bel 2428, BL-2428 M-928 Mary (Kind, kind and gentle is she) (T. Richardson; trad) Bel 2427, BL-2427 M-929 Mary of Argyll (Charles Jefferys; Sidney Nelson) Bel 2427, BL-2427 M-930 I'm lying on a foreign shore (The Scottish emigrant) (anon) Bel 2426, BL-2426 DAVID LAING (Aberdour, 1866 - ). “Pipe Major David Laing, on Highland bagpipes with augmented drone accompaniment” Recorded London, ca January 1911 Lxo-1269 A22145 Medley, Intro. Midlothian Pipe Band – march (Farquhar Beaton); The Glendruel Highlander – march (Alexander Fettes); Hot Punch – march (trad) Jumbo A-438; Ariel Grand 1503 Lxo-1271 A22147 The blue bonnets over the Border – march; The rocking stone of Inverness – strathspey; The piper o’ Drummond – reel (all trad) Jumbo 612; Ariel Grand 1504; Reg G-7527; RegAu G-7527 Lxo-1272 A22143 Medley of marches – Lord Lovat; MacKenzie Highlanders; Highland laddie (all trad) Jumbo 612; Ariel Grand 1504; Reg G-7528; RegAu G-7528 Lxo-1279 A22146 March – Pibroch o’ Donald Dhu; strathspey – Because he was a bonny lad; reel – De-il among the tailors (all trad) Jumbo A-438; Ariel Grand 1503 NOTE: Regal issues simply credited to “Pipe-Major David Laing”. -

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

Le Grand Film Marathon Man Mercredi 11 Novembre À 20.40

BULLETIN 46 SEMAINE 46 DU 07/11 AU 13/11 LE GRAND FILM MARATHON MAN MERCREDI 11 NOVEMBRE À 20.40 IL ÉTAIT UNE FOIS... LES ENFANTS DU PARADIS DIMANCHE 8 NOVEMBRE À 19.45 CYCLE AL PACINO DONNIE BRASCO JEUDI 12 NOVEMBRE À 20.40 LE GRAND FILM MARATHON MAN (-16), 1976, Couleur, VM, THR, de John Schlesinger, avec Dustin Hoffman, Laurence Olivier, Roy Scheider, William Devane Mercredi 11 novembre, découvrez Marathon Man, un thriller d’espionnage paranoïaque DIFFUSIONS : et haletant, avec un terrifiant Laurence Olivier et un grand Dustin Hoffman. Un sommet de psychose. 11/11 À 20.40 14/11 À 18.35 SYNOPSIS Babe Levy est un jeune étudiant new-yorkais, coureur de marathon. Son frère Doc, 27/11 À 20.40 membre d'une organisation gouvernementale secrète, est assassiné sous ses yeux. Babe 29/11 À 17.40 se retrouve alors au coeur d'un véritable cauchemar, poursuivi par le Dr Szell, un criminel de guerre nazi. Un grand thriller parano, avec au moins une scène anthologique : celle où Laurence Olivier torture Dustin Hoffman avec des instruments dentaires. AUTOUR DU FILM Ce film est tiré du roman Marathon Man de William Goldman, auteur connu des cinéphiles pour les scénarios de Butch Cassidy et le Kid, Les Hommes du Président, ou encore Maverick. Sept ans après Macadam Cowboy (1969), Dustin Hoffman et John Schlesinger s'associent de nouveau sur un thriller dont le scénario se nourrit de l’actualité enflammée de l’époque : Anciens nazis réfugiés et douloureux souvenir du maccarthysme. Dans cette intrigue sur fond d'opposition et de haine entre juifs et anciens nazis, le réalisateur distille une intrigue menée sur un rythme effréné, possédant un scénario dense, complexe et ter- riblement prenant. -

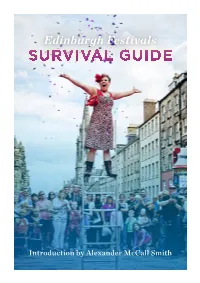

Survival Guide

Edinburgh Festivals SURVIVAL GUIDE Introduction by Alexander McCall Smith INTRODUCTION The original Edinburgh Festival was a wonderful gesture. In 1947, Britain was a dreary and difficult place to live, with the hardships and shortages of the Second World War still very much in evidence. The idea was to promote joyful celebration of the arts that would bring colour and excitement back into daily life. It worked, and the Edinburgh International Festival visitor might find a suitable festival even at the less rapidly became one of the leading arts festivals of obvious times of the year. The Scottish International the world. Edinburgh in the late summer came to be Storytelling Festival, for example, takes place in the synonymous with artistic celebration and sheer joy, shortening days of late October and early November, not just for the people of Edinburgh and Scotland, and, at what might be the coldest, darkest time of the but for everybody. year, there is the remarkable Edinburgh’s Hogmany, But then something rather interesting happened. one of the world’s biggest parties. The Hogmany The city had shown itself to be the ideal place for a celebration and the events that go with it allow many festival, and it was not long before the excitement thousands of people to see the light at the end of and enthusiasm of the International Festival began to winter’s tunnel. spill over into other artistic celebrations. There was How has this happened? At the heart of this the Fringe, the unofficial but highly popular younger is the fact that Edinburgh is, quite simply, one of sibling of the official Festival, but that was just the the most beautiful cities in the world. -

Vision 2019 Updating You on the Greyfriars Community

Vision 2019 Updating you on the Greyfriars Community Welcome/Fáilte! It has been two years since the Greyfriars Review was first published. Much has been happening in the Greyfriars community and therefore there is a lot to report! ‘Vision 2019’ aims to give you an update on what we have been doing and to outline future plans. Worship, the arts and community outreach are centered at our three locations – Greyfriars Kirk (GK), the Grassmarket Community Project (GCP) and the Greyfriars Charteris Centre (GCC). They are managed independently, but key members are common to all three organisations so the Greyfriars ethos and ideals are maintained. With enlarged teams, we are taking on more work and responsibilities within the parish and wider community. As with any organisation we are very dependent on our dedicated members, congregation, volunteers and staff to make things happen and are therefore very grateful to them all. We welcome new faces to be part of our community and if you would like to get involved, we will find a place for you. GREYFRIARS TEAM Rev Dr Richard Frazer Steve Lister Minister, Greyfriars Kirk Operations Manager, Greyfriars Kirk [email protected] [email protected] Rev Ken Luscombe Jonny Kinross Associate Minister, Greyfriars Kirk CEO, Grassmarket Community Project [email protected] [email protected] Jo Elliot Session Clerk, Greyfriars Kirk Daniel Fisher Manager, Greyfriars Charteris Centre [email protected] [email protected] Dan Rous Development Manager, Greyfriars Charteris Centre [email protected] 1 OUR ACHIEVEMENTS Greyfriars Kirk (GFK) • Established the University Campus Ministry based at the Greyfriars Charteris Centre. • Grown our congregation with new and contributing members. -

Scotland: BBC Weeks 51 and 52

BBC WEEKS 51 & 52, 18 - 31 December 2010 Programme Information, Television & Radio BBC Scotland Press Office bbc.co.uk/pressoffice bbc.co.uk/iplayer THIS WEEK’S HIGHLIGHTS TELEVISION & RADIO / BBC WEEKS 51 & 52 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ MONDAY 20 DECEMBER The Crash, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland TUESDAY 21 DECEMBER River City TV HIGHLIGHT BBC One Scotland WEDNESDAY 22 DECEMBER How to Make the Perfect Cake, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland THURSDAY 23 DECEMBER Pioneers, Prog 1/5 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Scotland on Song …with Barbara Dickson and Billy Connolly, NEW BBC Radio Scotland FRIDAY 24 DECEMBER Christmas Celebration, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC One Scotland Brian Taylor’s Christmas Lunch, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Watchnight Service, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland A Christmas of Hope, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland SATURDAY 25 DECEMBER Stark Talk Christmas Special with Fran Healy, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland On the Road with Amy MacDonald, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Stan Laurel’s Glasgow, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Christmas Classics, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland SUNDAY 26 DECEMBER The Pope in Scotland, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC One Scotland MONDAY 27 DECEMBER Best of Gary:Tank Commander TV HIGHLIGHT BBC One Scotland The Hebridean Trail, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Two Scotland When Standing Stones, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Another Country Legends with Ricky Ross, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland TUESDAY 28 DECEMBER River City TV HIGHLIGHT -

Access Statement

Access Statement The Pleasance Theatre Trust is committed to promoting equality and providing a welcoming and accessible environment for all its patrons, employees and performers, irrespective of their gender, gender reassignment, race, disability, sexual orientation, marital status, age, religion, belief or political affiliation. We are continually looking at how to better our facilities, procedures and training to create a fully inclusive and enjoyable festival experience. Over the last 5 years we have made significant progress in our commitment to accessibility. By working alongside our partners at the Edinburgh University, Edinburgh University Students’ Association and Edinburgh International Conference Centre, we have improved our facilities so that all of our performance spaces at our 3 main venues are now accessible for wheelchair users. We have also increased provision for access patrons in other ways, including offering all frontline festival staff disability awareness training and expanding the number of shows in our programme offering accessible performances within their run. We recognise that there is always more that can be done to improve the way our venue operates and we will endeavour to continually assess the accessibility of our venue and artistic programme. We are always open to new partnerships which will assist us in this venture and welcome any feedback either via the contact details below or through Euan’s Guide. Updated: May 2019 The Pleasance Theatre Trust Ltd Contact Us To contact us regarding access queries, please email [email protected] or call the box office on 0131 556 6550. We will try to respond to any enquiries as quickly as possible, however requests received outside of regular work hours may take slightly longer. -

Critchon's the Lavender Hill

1 The Lavender Hill Mob Directed by Charles Critchon. Produced by Michael Balcon. Screenplay and story by T.E. “Tebby” Clarke. Cinematography by Douglas Slocombe. Art Direction by William Kellner. Original Music by Georges Auric. Edited by Seth Holt. Costumes by Anthony Mendleson. Cinematic length: 81 minutes. Companies: Ealing Studos and the Rank Organisation. Cinematic release: June 1951. DVD release: 2002 DVD/Blue Ray 60th Anniversary Release 2011. Check for ratings. Rating 90%. All images are taken from the Public Domain and Wiki derivatives with permission. Written Without Prejudice Cast Alec Guinness as Henry Holland Stanley Holloway as Alfred Pendlebury Sid James as Lackery Wood Alfie Bass as Shorty Fisher John Gregson as Detective Farrow 2 Marjorie Fielding as Mrs. Chalk Edie Martin as Miss Evesham Audrey Hepburn as Chiquita John Salew as Parkin Ronald Adam as Turner Arthur Hambling as Wallis Gibb McLaughlin as Godwin Clive Morton as the Station Sergeant Sydney Tafler as Clayton Marie Burke as Senora Gallardo William Fox as Gregory Michael Trubshawe as the British Ambassador Jacques B. Brunius, Paul Demel, Eugene Deckers and Andreas Malandrinos as Customs Officials David Davies and Meredith Edwards as city policemen Cyril Chamberlain as Commander Moultrie Kelsall as a Detective Superintendent Christopher Hewett as Inspector Talbot Patrick Barr as a Divisional Detective Inspector Ann Heffernan as the kiosk attendant Robert Shaw as a lab technician Patricia Garwood as a schoolgirl Peter Bull as Joe the Gab Review Although Ealing Studios started making comedies in the later 1930s, the decade between 1947 and 1957, after which the studio was sold to the BBC and changed direction, was their classic period. -

Old Town Edinburgh

Investing in your gas supply Old Town Edinburgh We will soon be starting work in Edinburgh’s Old Town to upgrade our gas network in the High Street, Blackfriars Street, Cowgate, Holyrood Road and St John Street. Our essential work involves replacing old All businesses in the local area will remain metal pipework, which is around 120 years old, open as usual. We do have a compensation with modern plastic pipe. This will ensure a scheme in place for small businesses which continued safe and reliable gas supply for the suffer a genuine loss of trade because of our local community for many years to come. The work. Packs are available from our website, modern plastic pipe has a minimum lifespan of sgn.co.uk, via the Publications section. around 80 years. All being well, our work should be Following consultation with the local completed in October. authority, Police Scotland, Scottish Fire and Rescue Service and local bus companies, If you have any enquiries about this project, our work will start on Monday 20 March please call us on 0131 469 1728 during office and take approximately 28 weeks. hours (9am to 5pm) or on 0800 912 1700 outwith these times. We’ll do everything we can to minimise disruption. At times during our work there will You’ll find further details, such as where be some diversions and road closures in place, we’ll be working, overleaf. however, our work has been planned to be carried out in phases, and around high profile To explain more about our work we are events which take place in the area, to minimise holding a drop-in session at the Radisson inconvenience and keep traffic flowing. -

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook Illustrations of Edinburgh and other material collected by Sir Daniel Wilson, some of which he used in his Memorials of Edinburgh in the olden time (Edin., 1847). The following list gives possible sources for the items; some prints were published individually as well as appearing as part of larger works. References are also given to their use in Memorials. Quick-links within this list: Box I Box II Box III Abbreviations and notes Arnot: Hugo Arnot, The History of Edinburgh (1788). Bann. Club: Bannatyne Club. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated: W. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated in a series of views [ca. 1840]. Beauties of Scotland: R. Forsyth, The Beauties of Scotland (1805-8). Billings: R.W. Billings, The Baronial and ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland (1845-52). Black (1843): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1843). Black (1859): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1859). Edinburgh and Mid-Lothian (1838). Drawings by W.B. Scott, engraved by R. Scott. Some of the engravings are dated 1839. Edinburgh delineated (1832). Engravings by W.H. Lizars, mostly after drawings by J. Ewbank. They are in two series, each containing 25 numbered prints. See also Picturesque Views. Geikie, Etchings: Walter Geikie, Etchings illustrative of Scottish character and scenery, new edn [1842?]. Gibson, Select Views: Patrick Gibson, Select Views in Edinburgh (1818). Grose, Antiquities: Francis Grose, The Antiquities of Scotland (1797). Hearne, Antiquities: T. Hearne, Antiquities of Great Britain illustrated in views of monasteries, castles and churches now existing (1807). Heriot’s Hospital: Historical and descriptive account of George Heriot’s Hospital. With engravings by J. -

A Brief Look at the History of the Deaconess Hospital, Edinburgh

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2018; 48: 78–84 | doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2018.118 PAPER A brief look at the history of the Deaconess Hospital, Edinburgh, 1894–1990 HistoryER McNeill1, D Wright2, AK Demetriades 3& Humanities The Deaconess Hospital, Edinburgh, opened in 1894 and was the rst Correspondence to: establishment of its kind in the UK, maintained and wholly funded as it E McNeill Abstract was by the Reformed Church. Through its 96-year lifetime it changed and Chancellor’s Building evolved to time and circumstance. It was a school: for the training of nurses 48 Little France Crescent and deaconesses who took their practical skills all over the world. It was a Edinburgh EH16 45B sanctum: for the sick-poor before the NHS. It was a subsidiary: for the bigger UK hospitals of Edinburgh after amalgamation into the NHS. It was a specialised centre: as the Urology Department in Edinburgh and the Scottish Lithotripter centre. And now it is currently Email: student accommodation. There is no single source to account for its history. Through the use [email protected] of original material made available by the Lothian Health Services Archives – including Church of Scotland publications, patient records, a doctor’s casebook and annual reports – we review its conception, purpose, development and running; its fate on joining the NHS, its identity in the latter years and nally its closure. Keywords: Charteris, Church of Scotland, Deaconess Hospital, Pleasance Declaration of interests: No confl ict of interests declared Introduction Figure 1 Charteris Memorial Church, St Ninian’s and the Deaconess Hospital, 1944 On a November morning in 1888, two men stood in the Pleasance area of Edinburgh looking across the street to an old house, which 200 years before had been the town residence of Lord Carnegie.