Soil Survey Field and Laboratory Methods Manual; Soil Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sloping and Benching Systems

Trenching and Excavation Operations SLOPING AND BENCHING SYSTEMS OBJECTIVES Upon the completion of this section, the participant should be able to: 1. Describe the difference between maximum allowable slope and actual slope. 2. Observe how the angle of various sloped systems varies with soil type. 3. Evaluate layered systems to determine the proper trench slope. 4. Illustrate how shield systems and sloping systems interface in combination systems. ©HMTRI 2000 Page 42 Trenching REV1 Trenching and Excavation Operations SLOPING SYSTEMS If enough surface room is available, sloping or benching the trench walls will offer excellent protection without any additional equipment. Cutting the slope of the excavation back to its prescribed angle will allow the forces of cohesion (if present) and internal friction to hold the soil together and keep it from flowing downs the face of the trench. The soil type primarily determines the excavation angle. Sloping a method of protecting employees from caveins by excavating to form sides of an excavation that are inclined away from the excavations so as to prevent caveins. In practice, it may be difficult to accurately determine these sloping angles. Most of the time, the depth of the trench is known or can easily be determined. Based on the vertical depth, the amount of cutback on each side of the trench can be calculated. A formula to calculate these cutback distances will be included with each slope diagram. NOTE: Remember, the beginning of the cutback distance begins at the toe of the slope, not the center of the trench. Accordingly, the cutback distance will be the same regardless of how wide the trench is at the bottom. -

NRCS Keys to Soil Taxonomy

United States Department of Agriculture Keys to Soil Taxonomy Ninth Edition, 2003 Keys to Soil Taxonomy By Soil Survey Staff United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service Ninth Edition, 2003 The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call 202-720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Cover: A natric horizon with columnar structure in a Natrudoll from Argentina. 5 Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1: The Soils That We Classify.................................................................................. 9 Chapter 2: Differentiae for Mineral Soils and Organic Soils ............................................... 11 Chapter 3: Horizons and Characteristics Diagnostic for the Higher Categories ................. -

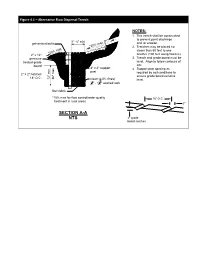

SECTION A-A NTS 2" Grade Board Notches

Figure 4.1 – Alternative Flow Dispersal Trench NOTES: 1. This trench shall be constructed to prevent point discharge 1' - 6" min galvanized bolts and /or erosion. *20% max 2. Trenches may be placed no closer than 50 feet to one *20% max 2" x 12" another (100 feet along flowline). pressure 3. Trench and grade board must be treated grade level. Align to follow contours of board site. 4" x 4" support 4. Support post spacing as post required by soil conditions to 2" x 2" notches ensure grade board remains 18" O.C. 36" max 12" min. clean (< 5% fines) level. 3 1 4" - 1 2" washed rock filter fabric *15% max for flow control/water quality 18" O.C. treatment in rural areas 2" SECTION A-A NTS 2" grade board notches Figure 4.2 – Pipe Compaction Design and Backfill O.D. O.D. limits of pipe W (see note 4) 3' max. 3' max. compaction limit of pipe zone 1' - 0" bedding material for flexible 1' - 0" pipe (see 0.15 O.D. min. note 6) B O.D. limits of pipe compaction 0.65 O.D. min. foundation level A* gravel backfill gravel backfill for for pipe bedding foundations when specified * A = 4" min., 27" I.D. and under 6" min., over 27" I.D. A. Metal and Concrete Pipe Bedding for Flexible Pipe span span span 3' max Flexible Pipe NOTES: 3' max 3' max 1. Provide uniform support under barrels. 1'-0" 2. Hand tamp under haunches. 3. Compact bedding material to 95% max. -

Simple Soil Tests for On-Site Evaluation of Soil Health in Orchards

sustainability Article Simple Soil Tests for On-Site Evaluation of Soil Health in Orchards Esther O. Thomsen 1, Jennifer R. Reeve 1,*, Catherine M. Culumber 2, Diane G. Alston 3, Robert Newhall 1 and Grant Cardon 1 1 Dept. Plant Soils and Climate, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322, USA; [email protected] (E.O.T.); [email protected] (R.N.); [email protected] (G.C.) 2 UC Cooperative Extension, Fresno, CA 93710, USA; [email protected] 3 Dept. Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 September 2019; Accepted: 26 October 2019; Published: 29 October 2019 Abstract: Standard commercial soil tests typically quantify nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, pH, and salinity. These factors alone are not sufficient to predict the long-term effects of management on soil health. The goal of this study was to assess the effectiveness and use of simple physical, biological, and chemical soil health indicator tests that can be completed on-site. Analyses were conducted on soil samples collected from three experimental peach orchards located on the Utah State Horticultural Research Farm in Kaysville, Utah. All simple tests were correlated to comparable lab analyses using Pearson’s correlation. The highest positive correlations were found between Solvita®respiration, and microbial biomass (R = 0.88), followed by our modified slake test and microbial biomass (R = 0.83). Both Berlese funnel and pit count methods of estimating soil macro-organism diversity were fairly predictive of soil health. Overall, simple commercially available chemical tests were weak indicators of soil nutrient concentrations compared to laboratory tests. -

AAHS New Objective Grading System to Provide Prognostic Value To

New Objective Grading System to Provide Prognostic Value to Cubital Tunnel Surgery Cory Lebowitz, DO; Lauryn Bianco, MS; Manuel Pontes, PhD; Mitchel K. Freedman, DO; Michael Rivlin, MD INTRODUCTION TABLE 1: ELECTRODIAGNOSTIC GRADING SYSTEM RESULTS CONCLUSION • The use of electrodiagnostic (EDX) • • 101 patients; 60 male & 41 Electrodiagnostic studies is well documented on its female studies not only aid a value as diagnostic tool, however, little clinical diagnosis of is known about its prognostic value for • Overall quickDASH went from 38 to 41 CuTS but can cubital tunnel surgery (CuTS) provide a framework • We report which EDX results yield • Discovered a cut off of a for the outcome of prognostic value for the surgical Sensory Amplitude of 38 treatment for CuTS based on patients surgery • We form an EDX based grading quickDASH improvement • system for CuTS that is predictive of • Patients with a sensory Specifically when outcome amplitude that was looking at the considered normal MCV across the METHODS based off the literature elbow with the but abnormal (i.e <38) sensory • Patients with CuTS were treated based off our data amplitude surgically with an ulnar nerve failed to improve in decompression +/- transposition their quickDASH • The grading system • Pre & Postoperative quickDASH scores is reproducible and scores and demographics reviewed • 97 patients (96%) fit in to can aid in following • Preoperative EDX reviewed: similar patient for • EMG the grading system • 93.8% inter-observer outcome evaluation • Motor Amplitudes and clinical studies • Motor Conduction Velocities reliability to use the • Sensory Amplitude grading system • Conduction Block • Those with a grade 3 had • Grading system constructed solely on the largest quickDASH EDX: nerve conduction studies and improvement electromyography variable. -

Soil Testing Can Help Nutrient Deficiencies Or Imbalances

Do You Have Problems With: • Nutrient deficiencies in crops • Poor plant growth and response from applied fertilizers • Hard to manage weeds • Low crop yields • Poor quality forages • Irregular plant growth in your fields • Managing manure or compost applications Soil tests help to identify production problems related to Soil Testing Can Help nutrient deficiencies or imbalances. Above: Nitrogen defi- ciency in corn (photo: Ryan Stoffregen, Illinois). Below: Phosphorus deficiency in corn. Source: www.ipni.net Benefits of Soil Testing: • Determines nutrient levels in the soil • Determines pH levels (lime needs) • Provides a decision making tool to determine what nutrients to apply and how much • Potential for higher yielding crops • Potential for higher quality crops • More efficient fertilizer use Costs: Generally soil tests cost $7 to $10.00 per sample. The costs of soil tests vary depending on: 1. Your state (some states offer free soil testing) 2. The lab that is used. 3. The items being tested for (the cost increases as more nutrients are being analyzed). NOTE: Some state agencies and land grant universities provide free soil testing for the basic soil test items (pH, available phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium, and organic matter). Additional costs may be charged for testing for micronutrients. In other states, all soil testing is done by private labs and generally charge $7-$10 for the basic test. One soil test should be taken for each field, or for each 20 acres within a field. See example on page 3. Soil Testing How Often Should I Soil Test? Generally, you should soil test every 3-5 years or more often if manure is applied or you are trying to make large nutrient or pH changes in the soil. -

Electrophysiological Grading of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Electrophysiological Grading of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome MUHAMMAD WAZIR ALI KHAN ABSTRACT Background: Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS) is the most common entrapment neuropathy caused by a conduction block of distal median nerve at wrist. Women are affected more commonly than men. Clinical signs are quite helpful in diagnosis but electrophysiological tests yield accurate diagnosis and severity grading along with follow-up and management. Aim: To utilize nerve conduction studies (NCS) to diagnose carpal tunnel syndrome and further classify its severity according to the AAEM criteria. Methods: This descriptive study was conducted at the Department of Neurology, Sh. Zayed Medical College/Hospital, Rahim Yar Khan from June 2013 to Dec 2014. Overall, 90 patients and 180 hands were evaluated through nerve conduction studies. Patients with clinically high suspicion of CTS were included for NCS. Clinical grading was done using the AAEM criteria for CTS. Other variables like duration of symptoms, handedness, bilateral disease and gender were noted. Mean and median were calculated for age of the patients. Results: Ninety patients and 126 hands were identified with carpal tunnel syndrome. Most patients (80%) were females with age range from 19 to 75 years. More than one third had bilateral disease. Dominant hand was involved in majority of the patients. Most patients had (42.8%) severe CTS as per AAEM criteria. Also duration of symptoms directly correlated with severity of disease. Conclusion: Nerve conduction study is a valuable tool in accurate diagnosis and grading of carpal tunnel syndrome. Keywords: Phalen sign, Tinel Sign, electrophysiology, median nerve INTRODUCTION 4,5,6 electrophysiological findings, are quite valuable . -

Soil Taxonomy" in Particular ,

1. CONTROL NUMBER 2. SUBECT CLASSIFICATION (695) BIBLIOGRAPItlC DATA SHEET IN-AAJ-558 AF26-0000-0000 3. TITLE ANt) SUBTITLE (240) Experimental designs for predicting crop productivity with environmental and economic inputs for al rotcchnology transfer 4. PERSON.\I. AUTHORS (10P) Silva, J. A. 5. CORPORATE AUTHORS (101) Hawaii Univ. College of Tropical Agriculture 6. IDOCUMEN2< DATE (110)7. NUMBER OF PAGES (120) 8.ARC NUMBER [7 1981 13n631.5.S586b __ 9. R FRENCE ORGANIZATION (130) Hawaii 10. SUPI'PLEMENTARY NOTES (500) (In Departmental paper 49) 11. ABSTRACT (950) 12. DESCRIPTORS (920) 13. PROJECT NUMBER (150) Agricultural production Agricultural technology 931582C00 Technology transferi!Techoloy tansferYieldY e d14. CONTRACT NO.(I It)) 15. CONTRACT Soil fertility Experimentation TYPE (140) Tropics Productivity AID/ta-C-1108 Forecasting 16. TYPE OF DOCUMENT (160) AM 590-7 (10-79) Departmental Paper 49 Experimental Designs for Predicting Crop Productivity with Environmental and Economic Inputs for Agrotechnology Transfer Edited by James A. Silva ...... ,..,... *** .......... ....* ...... .... .. 00400O 00€€€€*00 .. ...* Y Y*b***S4....... ~~~.eeeeeoeeeeeU ........ o .. *.4.............*e............ :0 ooee............. ........... ....... nae of T c.e Haw i. ns..ut. CollegeofTrpclgr.cut a UnversityoHa B....EMAR.SO University of Hawaiio~ee BENCHMAR SO I Le~eSPoJECTU/ADCotac o.t-C1 14.. C4 '4 t 10 wte IA:A 77 d E/ Adt , I 26Esi ',. ,~ )~'I *3-! * Ire ~ -I ~ 0 1 N Koel4 'I M M Experimental Designs for Predicting Crop Productivity with Environmental and Economic Inputs for Agrotechnology Transfer Edited by James A. Silva Benchmark Soils Project UH/AiD Contract No. to-C-1108 The Author James A. Silva is Soil Scientist and Principal Investigator, Benchmark Soils Project/Hawaii, Department of Agronomy and Soil Science, College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, University of Hawaii, Honolulu. -

Sustainable Use of Soils and Water: the Role of Environmental Land Use Conflicts

sustainability Editorial Sustainable Use of Soils and Water: The Role of Environmental Land Use Conflicts Fernando A. L. Pacheco CQVR – Chemistry Research Centre, University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro, Quinta de Prados Ap. 1013, Vila Real 5001-801, Portugal; [email protected] Received: 3 February 2020; Accepted: 4 February 2020; Published: 6 February 2020 Abstract: Sustainability is a utopia of societies, that could be achieved by a harmonious balance between socio-economic development and environmental protection, including the sustainable exploitation of natural resources. The present Special Issue addresses a multiplicity of realities that confirm a deviation from this utopia in the real world, as well as the concerns of researchers. These scholars point to measures that could help lead the damaged environment to a better status. The studies were focused on sustainable use of soils and water, as well as on land use or occupation changes that can negatively affect the quality of those resources. Some other studies attempt to assess (un)sustainability in specific regions through holistic approaches, like the land carrying capacity, the green gross domestic product or the eco-security models. Overall, the special issue provides a panoramic view of competing interests for land and the consequences for the environment derived therefrom. Keywords: water resources; soil; land use change; conflicts; environmental degradation; sustainability Competition for land is a worldwide problem affecting developed as well as developing countries, because the economic growth of activity sectors often requires the expansion of occupied land, sometimes to places that overlap different sectors. Besides the social tension and conflicts eventually caused by the competing interests for land, the environmental problems they can trigger and sustain cannot be overlooked. -

Fire and Emergency Medical Services Operations and Data Analysis Flint, Michigan Center for Public Safety Management

Fire and Emergency Medical Services Operations and Data Analysis Flint, Michigan December 2014 FIRE EMS Operational Analysis Center for Public Safety Management 474 K Street, NW, Suite 702 Washington, DC 20001 www.cpsm.us – 716-969-1360 Exclusive Provider of Public Safety Technical Assistance for the International City/County Management Association General Information About ICMA The International City/County Management Association (ICMA) is a 100-year-old, nonprofit professional association of local government administrators and managers, with approximately 9,000 members located in 32 countries. Since its inception in 1914, ICMA has been dedicated to assisting local governments in providing services to its citizens in an efficient and effective manner. Its work spans all of the activities of local government—parks, libraries, recreation, public works, economic development, code enforcement, brownfields, public safety, etc. ICMA advances the knowledge of local government best practices across a wide range of platforms including publications, research, training, and technical assistance. ICMA’s work includes both domestic and international activities in partnership with local, state, and federal governments as well as private foundations. For example, it is involved in a major library research project funded by the Bill &Melinda Gates Foundation and it is providing community policing training in Panama working with the U.S. State Department. It worked in Afghanistan assisting with building wastewater treatment plants and has teams in Central America working with SOUTHCOM to provide training in disaster relief. Center for Public Safety Management LLC The ICMA Center for Public Safety Management (ICMA/CPSM) is one of four Centers within the Information and Assistance Division of ICMA providing support to local governments in the areas of police, fire, EMS, emergency management, and homeland security. -

Good Practices for the Preparation of Digital Soil Maps

UNIVERSIDAD DE COSTA RICA CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIONES AGRONÓMICAS FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS AGROALIMENTARIAS GOOD PRACTICES FOR THE PREPARATION OF DIGITAL SOIL MAPS Resilience and comprehensive risk management in agriculture Inter-american Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture University of Costa Rica Agricultural Research Center UNIVERSIDAD DE COSTA RICA CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIONES AGRONÓMICAS FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS AGROALIMENTARIAS GOOD PRACTICES FOR THE PREPARATION OF DIGITAL SOIL MAPS Resilience and comprehensive risk management in agriculture Inter-american Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture University of Costa Rica Agricultural Research Center GOOD PRACTICES FOR THE PREPARATION OF DIGITAL SOIL MAPS Inter-American institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA), 2016 Good practices for the preparation of digital soil maps by IICA is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/) Based on a work at www.iica.int IICA encourages the fair use of this document. Proper citation is requested. This publication is also available in electronic (PDF) format from the Institute’s Web site: http://www.iica. int Content Editorial coordination: Rafael Mata Chinchilla, Dangelo Sandoval Chacón, Jonathan Castro Chinchilla, Foreword .................................................... 5 Christian Solís Salazar Editing in Spanish: Máximo Araya Acronyms .................................................... 6 Layout: Sergio Orellana Caballero Introduction .................................................. 7 Translation into English: Christina Feenny Cover design: Sergio Orellana Caballero Good practices for the preparation of digital soil maps................. 9 Printing: Sergio Orellana Caballero Glossary .................................................... 15 Bibliography ................................................. 18 Good practices for the preparation of digital soil maps / IICA, CIA – San Jose, C.R.: IICA, 2016 00 p.; 00 cm X 00 cm ISBN: 978-92-9248-652-5 1. -

A New Era of Digital Soil Mapping Across Forested Landscapes 14 Chuck Bulmera,*, David Pare´ B, Grant M

CHAPTER A new era of digital soil mapping across forested landscapes 14 Chuck Bulmera,*, David Pare´ b, Grant M. Domkec aBC Ministry Forests Lands Natural Resource Operations Rural Development, Vernon, BC, Canada, bNatural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Laurentian Forestry Centre, Quebec, QC, Canada, cNorthern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, St. Paul, MN, United States *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Soil maps provide essential information for forest management, and a recent transformation of the map making process through digital soil mapping (DSM) is providing much improved soil information compared to what was available through traditional mapping methods. The improvements include higher resolution soil data for greater mapping extents, and incorporating a wide range of environmental factors to predict soil classes and attributes, along with a better understanding of mapping uncertainties. In this chapter, we provide a brief introduction to the concepts and methods underlying the digital soil map, outline the current state of DSM as it relates to forestry and global change, and provide some examples of how DSM can be applied to evaluate soil changes in response to multiple stressors. Throughout the chapter, we highlight the immense potential of DSM, but also describe some of the challenges that need to be overcome to truly realize this potential. Those challenges include finding ways to provide additional field data to train models and validate results, developing a group of highly skilled people with combined abilities in computational science and pedology, as well as the ongoing need to encourage communi- cation between the DSM community, land managers and decision makers whose work we believe can benefit from the new information provided by DSM.