Journal of Black Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Da Brat Unrestricted Mp3, Flac, Wma

Da Brat Unrestricted mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Unrestricted Country: UK Released: 2000 MP3 version RAR size: 1341 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1725 mb WMA version RAR size: 1814 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 151 Other Formats: FLAC MP3 AHX AU MOD MP1 MMF Tracklist Hide Credits Intro A1 1:58 Featuring – Millie Jackson, TwistaProducer – Jermaine Dupri, Timbaland We Ready A2 4:00 Co-producer – Carl So-LoweFeaturing – Jermaine Dupri, Lil' JonProducer – Jermaine Dupri What'Chu Like A3 3:41 Co-producer – Bryan-Michael CoxProducer – Jermaine DupriVocals – Tyrese At The Club (Interlude) A4 0:38 Vocals – Alicia Keys, Ice Cold Fuck You A5 2:45 Producer – Jermaine Dupri Back Up B1 4:08 Featuring – Ja RuleProducer – Jermaine DupriVocals – Tamara Savage Hands In The Air B2 3:49 Featuring – MystikalProducer – Deric "D-Dot" Angelettie Runnin' Out Of Time B3 4:14 Producer – Aaron PittmanVocals – Kelly Price That's What I'm Looking For B4 3:44 Producer – Jermaine Dupri Breeve On Em C1 3:53 Featuring – Twenty IIProducer – Aaron Pittman What's On Ya Mind C2 Co-producer – Carl So-LoweFeaturing – Twenty IIProducer – Jermaine DupriVocals – 4:08 LaTocha Scott, Trey Lorenz C3 Leave Me Alone (Interlude) 0:17 High Come Down C4 3:06 Producer – Jermaine DupriVocals – LaTocha Scott, Trey Lorenz All My Bitches D1 3:57 Co-producer – Bryan-Michael CoxProducer – Jermaine Dupri Pink Lemonade D2 3:50 Co-producer – Carl So-LoweProducer – Jermaine Dupri D3 A Word From...Da Bishop Don "Magic" Juan (Interlude) 0:19 Chi Town D4 4:06 Producer – Kanye WestVocals [Additional] – LaJoyce Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Columbia, Sony COL 491780 2, COL 491780 2, Unrestricted (CD, Music 4917802000, Da Brat 4917802000, Europe 2000 Album) Entertainment Inc., none none So So Def Unrestricted (CDr, Sony Music none Da Brat none Europe 2000 Album, Promo) Entertainment Inc. -

Hip Hop Pedagogies of Black Women Rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Guillory, Nichole Ann, "Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 173. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/173 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SCHOOLIN’ WOMEN: HIP HOP PEDAGOGIES OF BLACK WOMEN RAPPERS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Nichole Ann Guillory B.S., Louisiana State University, 1993 M.Ed., University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 1998 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 Nichole Ann Guillory All Rights Reserved ii For my mother Linda Espree and my grandmother Lovenia Espree iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am humbled by the continuous encouragement and support I have received from family, friends, and professors. For their prayers and kindness, I will be forever grateful. I offer my sincere thanks to all who made sure I was well fed—mentally, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. I would not have finished this program without my mother’s constant love and steadfast confidence in me. -

1 | P a G E CITY of SALEM BOARD of HEALTH MEETING MINUTES

CITY OF SALEM BOARD OF HEALTH MEETING MINUTES SPECIAL MEETING Virtual Meeting held via Zoom and Recorded by SATV December 17, 2020 MEMBERS PRESENT: Dr. Jeremy Schiller, Paul Kirby, Geraldine Yuhas, Sara Moore, Datanis Elias OTHERS PRESENT: David Greenbaum, Health Agent, Maureen Davis, Clerk of the Board, Patti Morsillo, City Council Liaison, Mayor Kimberley Driscoll ATTENDEES ADDRESSED: Several (please see minutes) TOPIC DISCUSSION/ACTION J. Schiller read aloud that, pursuant to Governor Baker’s orders, there exists COVID-19 Emergency Open Meeting Law Guidance regarding the implementation of virtual public meetings, etc. 1. Call to Order 7:04pm 2. Discussion and vote on additional J. Schiller thanked all participants, including the Mayor. There are a COVID restrictions, including tremendous number of participants viewing. He said this is not a meeting rolling back to Phase 2, Step 2 of we wanted to be having, but the trajectory is such that it required a meeting the Commonwealths phased like this to consider a rollback. He has received the most amount of reopening process responses he has ever received from the public since he has been on the Board and they have had a big impact on him. The responses highlighted just how much exercise means to people. There were some comments about museums as well. He said we are considering this rollback at a time when cases are spiking. We are now in the red, hospital admissions are way up, and capacity is entering a real critical phase. Museums and gyms are not being particularly targeted. This is a state-wide phase and protocol that the Governor set up in the beginning back in March. -

1001 Quick, Healthy and Nutritious Recipes for Everyone to Eat Well Everyday

THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE INSTANT POT COOKBOOK : 1001 QUICK, HEALTHY AND NUTRITIOUS RECIPES FOR EVERYONE TO EAT WELL EVERYDAY Author: Jasmine Anderson Number of Pages: 262 pages Published Date: 10 Jun 2020 Publisher: Jasmine Anderson Publication Country: none Language: English ISBN: 9781801240215 DOWNLOAD: THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE INSTANT POT COOKBOOK : 1001 QUICK, HEALTHY AND NUTRITIOUS RECIPES FOR EVERYONE TO EAT WELL EVERYDAY The Most Comprehensive Instant Pot Cookbook : 1001 Quick, Healthy and Nutritious Recipes for Everyone to Eat Well Everyday PDF Book "You can say goodbye to the diet fad of the month and say hello to an easy-to-follow program with wonderful, long-lasting results. By the end of the Second World War, Jowett had modified the pre-war commercial and re-named it the Bradford. This is, perhaps, surprising given that GH deficiency (GHD) in adulthood had been 'recognized' as long ago as the 1960s. Biofuels such as bioethanol, biodiesel, bio-oil, and biohydrogen are produced using technologies for thermochemically and biologically converting biomass. Your journal contains the answers to your most burning questions. They deliver solid advice on hiring an illustrator-or not; participating in workshops and conferences to learn the business and hone a story; finding an agent; and, finally, submitting the manuscript to publishers and - if you are successful-signing a contract. You'll learn to deal with localization issues such as time zones and translations, and to customize the look and feel of an APEX website to blend in with your corporate branding strategy. In between cups of tea, rounds of toast and the occasional 'cuddle' with Mrs Naked Trader, he describes the straightforward techniques that have enabled him to succeed in the markets and escape the rat race. -

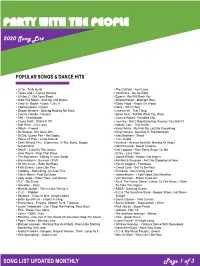

View the Full Song List

PARTY WITH THE PEOPLE 2020 Song List POPULAR SONGS & DANCE HITS ▪ Lizzo - Truth Hurts ▪ The Outfield - Your Love ▪ Tones And I - Dance Monkey ▪ Vanilla Ice - Ice Ice Baby ▪ Lil Nas X - Old Town Road ▪ Queen - We Will Rock You ▪ Walk The Moon - Shut Up And Dance ▪ Wilson Pickett - Midnight Hour ▪ Cardi B - Bodak Yellow, I Like It ▪ Eddie Floyd - Knock On Wood ▪ Chainsmokers - Closer ▪ Nelly - Hot In Here ▪ Shawn Mendes - Nothing Holding Me Back ▪ Lauryn Hill - That Thing ▪ Camila Cabello - Havana ▪ Spice Girls - Tell Me What You Want ▪ OMI - Cheerleader ▪ Guns & Roses - Paradise City ▪ Taylor Swift - Shake It Off ▪ Journey - Don’t Stop Believing, Anyway You Want It ▪ Daft Punk - Get Lucky ▪ Natalie Cole - This Will Be ▪ Pitbull - Fireball ▪ Barry White - My First My Last My Everything ▪ DJ Khaled - All I Do Is Win ▪ King Harvest - Dancing In The Moonlight ▪ Dr Dre, Queen Pen - No Diggity ▪ Isley Brothers - Shout ▪ House Of Pain - Jump Around ▪ 112 - Cupid ▪ Earth Wind & Fire - September, In The Stone, Boogie ▪ Tavares - Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel Wonderland ▪ Neil Diamond - Sweet Caroline ▪ DNCE - Cake By The Ocean ▪ Def Leppard - Pour Some Sugar On Me ▪ Liam Payne - Strip That Down ▪ O’Jay - Love Train ▪ The Romantics -Talking In Your Sleep ▪ Jackie Wilson - Higher And Higher ▪ Bryan Adams - Summer Of 69 ▪ Ashford & Simpson - Ain’t No Stopping Us Now ▪ Sir Mix-A-Lot – Baby Got Back ▪ Kenny Loggins - Footloose ▪ Faith Evans - Love Like This ▪ Cheryl Lynn - Got To Be Real ▪ Coldplay - Something Just Like This ▪ Emotions - Best Of My Love ▪ Calvin Harris - Feel So Close ▪ James Brown - I Feel Good, Sex Machine ▪ Lady Gaga - Poker Face, Just Dance ▪ Van Morrison - Brown Eyed Girl ▪ TLC - No Scrub ▪ Sly & The Family Stone - Dance To The Music, I Want ▪ Ginuwine - Pony To Take You Higher ▪ Montell Jordan - This Is How We Do It ▪ ABBA - Dancing Queen ▪ V.I.C. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

Missy Elliott Supa Dupa Fly Torrent Download Supa Dupa Fly

missy elliott supa dupa fly torrent download Supa Dupa Fly. Arguably the most influential album ever released by a female hip-hop artist, Missy "Misdemeanor" Elliott's debut album, Supa Dupa Fly, is a boundary-shattering postmodern masterpiece. It had a tremendous impact on hip-hop, and an even bigger one on R&B, as its futuristic, nearly experimental style became the de facto sound of urban radio at the close of the millennium. A substantial share of the credit has to go to producer Timbaland, whose lean, digital grooves are packed with unpredictable arrangements and stuttering rhythms that often resemble slowed-down drum'n'bass breakbeats. The results are not only unique, they're nothing short of revolutionary, making Timbaland a hip name to drop in electronica circles as well. For her part, Elliott impresses with her versatility -- she's a singer, a rapper, and an equal songwriting partner, and it's clear from the album's accompanying videos that the space-age aesthetic of the music doesn't just belong to her producer. She's no technical master on the mic; her raps are fairly simple, delivered in the slow purr of a heavy-lidded stoner. Yet they're also full of hilariously surreal free associations that fit the off-kilter sensibility of the music to a tee. Actually, Elliott sings more on Supa Dupa Fly than she does on her subsequent albums, making it her most R&B-oriented effort; she's more unique as a rapper than she is as a singer, but she has a smooth voice and harmonizes well. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Amy Smith-Stewart

Suzanne McClelland Just Left Feel Right Suzanne McClelland Just Left Feel Right The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum third party by Amy Smith-Stewart I’m not sure what “coming out right” means. It often means that what you do holds a kind of energy that you wouldn’t just put there, that comes about through grace of some sort. - Jasper Johns1 Sweet, crazy conversations full of half sentences, daydreams and misunderstandings more thrilling than understanding could ever be. – Toni Morrison2 Suzanne McClelland has spent her thirty-year career collecting messaging. Words she overhears, sounds she absorbs, and data she gathers. Mining the methods of its application, and the implications of meaning, McClelland compiles research, combing what is said, what is streamed, what trends; hoarding symptomatic information that drops in and out of our lives. This focused twenty-seven-year survey, 1990 to 2017, concentrates on works that range from painting to installation, glass, ceramic, and works on paper, from specific periods of her career that all share a distinctive commonality; they capture the eruptive and disparate voices of a shifting American vernacular and its rippling effect on the way we communicate and, hence, how we understand each other. Many of the works in the exhibition are being presented for the first time, others have rarely been seen, and some haven’t been shown since their debut. McClelland’s rich and investigational practice tracks the ways we have changed our modalities of communication over three decades. She has said on numerous occasions that, for her, reading and listening represent “political actions”3 and her inimitable methodology envisages these activities. -

Black Women Queering the Mic: Missy Elliott Disturbing the Boundaries of Racialized Sexuality and Gender

Journal of Homosexuality, 58:775–792, 2011 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0091-8369 print/1540-3602 online DOI: 10.1080/00918369.2011.581921 Black Women Queering the Mic: Missy Elliott Disturbing the Boundaries of Racialized Sexuality and Gender NIKKI LANE, PhD Candidate Department of Anthropology, American University, Washington, DC, USA Though there were and always have been djs, dancers, graffiti artists, and rappers who were Black women, they are placed on the periphery of hip-hop culture; their voices, along with “gay rap- pers” and “white rappers” devalued and their contribution to the global rise of hip-hop either forgotten or eschewed. This article is an attempt to articulate the existence of Black women who work outside of the paradigms of the “silence, secrecy, and a partially self-chosen invisibility” that Evelynn Hammonds describes. At the center of this article lies an attempt to locate a new configura- tion and expression of desire and sexuality, opening a door, wide open, to gain a different view of Black women, their sexuality, their expression of it, and the complexities that arise when they attempt to express it in hip hop nation language. KEYWORDS Black women, hip-hop, linguistic anthropology, queer, rap INTRODUCTION Cecilia Cutler (2003) writes that “there is a powerful discourse within hip-hop that privileges the black body and the black urban street experi- ence” (p. 212). What is important to understand, however, is that there is a particular gendered Black body that is privileged in hip hop. The body is of the urban Black heterosexual male, and his set of experiences shape not only the discourse, but also the language of hip hop itself. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR.