The Prison-Televisual Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July-August 2018

111 The Chamber Spotlight, Saturday, July 7, 2018 – Page 1B INS IDE THIS ISSUE Vol. 10 No. 3 • July - August 2018 ALLIED MEMORIAL REMEMBRANCE RIDE FLIGHTS Of OUR FATHERS AIR SHOW AND FLY-IN NORTH TEXAS ANTIQUE TRACTOR SHOW The Chamber Spotlight General Dentistry Flexible Financing Cosmetic Procedures Family Friendly Atmosphere Sedation Dentistry Immediate Appointments 101 E. HigH St, tErrEll • 972.563.7633 • dralannix.com Page 2B – The Chamber Spotlight, Saturday, July 7, 2018 T errell Chamber of Commerce renewals April 26 – June 30 TIger Paw Car Wash Guest & Gray, P.C. Salient Global Technologies Achievement Martial Arts Academy LLC Holiday Inn Express, Terrell Schaumburg & Polk Engineers Anchor Printing Hospice Plus, Inc. Sign Guy DFW Inc. Atmos Energy Corporation Intex Electric STAR Transit B.H. Daves Appliances Jackson Title / Flowers Title Blessings on Brin JAREP Commercial Construction, LLC Stefco Specialty Advertising Bluebonnet Ridge RV Park John and Sarah Kegerreis Terrell Bible Church Brenda Samples Keith Oakley Terrell Veterinary Center, PC Brookshire’s Food Store KHYI 95.3 The Range Texas Best Pre-owned Cars Burger King Los Laras Tire & Mufflers Tiger Paw Car Wash Chubs Towing & Recovery Lott Cleaners Cole Mountain Catering Company Meadowview Town Homes Tom and Carol Ohmann Colonial Lodge Assisted Living Meridith’s Fine Millworks Unkle Skotty’s Exxon Cowboy Collection Tack & Arena Natural Technology Inc.(Naturtech) Vannoy Surveyors, Inc. First Presbyterian Church Olympic Trailer Services, Inc. Wade Indoor Arena First United Methodist Church Poetry Community Christian School WalMart Supercenter Fivecoat Construction LLC Poor Me Sweets Whisked Away Bake House Flooring America Terrell Power In the Valley Ministries Freddy’s Frozen Custard Pritchett’s Jewelry Casting Co. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Praise Prime Time

August 17 - 23, 2019 Adam Devine, Danny McBride, Edi Patterson and John Goodman star in “The Righteous Gemstones” AUTO HOME FLOOD LIFE WORK Praise 101 E. Clinton St., Roseboro, N.C. 910-525-5222 prime time [email protected] We ought to weigh well, what we can only once decide. SEE WHAT YOUR NEIGHBORS Complete Funeral Service including: Traditional Funerals, Cremation Pre-Need-Pre-Planning Independently Owned & Operated ARE TALKING ABOUT! Since 1920’s FURNITURE - APPLIANCES - FLOOR COVERING ELECTRONICS - OUTDOOR POWER EQUIPMENT 910-592-7077 Butler Funeral Home 401 W. Roseboro Street 2 locations to Hwy. 24 Windwood Dr. Roseboro, NC better serve you Stedman, NC www.clintonappliance.com 910-525-5138 910-223-7400 910-525-4337 (fax) 910-307-0353(fax) Sampson Independent — Saturday, August 17, 2019 — Page 3 Sports This Week SATURDAY 9:55 p.m. WUVC MFL Fútbol Morelia From Pinehurst Resort and Country season. From Broncos Stadium at Mile 8:00 a.m. ESPN Get Up! (Live) (2h) 8:00 p.m. WRAZ NFL Football Jack- at Club América. From Estadio Azteca-- Club-- Pinehurst, N.C. (Live) (3h) High-- Denver, Colo. (Live) (3h) ESPN2 SportsCenter (1h) sonville Jaguars at Miami Dolphins. 7:00 a.m. DISC Major League Fishing Mexico City, Mexico (Live) (2h05) 4:00 p.m. WNCN NFL Football New ESPN2 Baseball Little League World 9:00 a.m. ESPN2 SportsCenter (1h) Pre-season. From Hard Rock Stadi- (2h) 10:00 p.m. WRDC Ring of Honor Orleans Saints at Los Angeles Chargers. Series. From Howard J. Lamade Stadi- 10:00 a.m. -

City Court Lists August Trial Docket

HHERALDING OOVER A CCENTURY OF NNEWS CCOVERAGE •• 1903-20121903-2012 LIFESTYLES SPORTS INSIDE NSU OPENS BOOK AGAINST PROMOTING SIGNING TEXAS TECH GOOD GRADES See Page 6A See Page 8A See Page 2A The Natchitoches Times And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free, John 8:32. Friday, August 31, 2012 Natchitoches, Louisiana • Since 1714 Fifty Cents the Copy Letters to the Editor Let us know what you think, City Court lists write a letter to the editor. See Page 4A for details. Natchitoches Times e-mail [email protected] August trial docket Visit our website at: www.natchitochestimes.com City Court Judge Fred loud music amended disturb- Gahagan lists the trial docket ing the peace, pleaded guilty, WEATHER for Aug. 8. sentence of the court was, HIGH LOW Sharneika Adley, disturb- confine 30 days in jail, 30 days ing the peace/fighting, simple in jail suspended, 6 months 95 76 criminal damage to property, unsupervised probation, pay dismissed. fine and cost totaling $278, Colonda Slate Bell, disturb- default of payment 20 days in Area Deaths ing the peace/fighting, BW jail. failure to appear. Christopher Jackson, loud Obituaries Page 2A Julie Clare Cobb, theft by music amended disturbing shoplifting, dismissed. the peace, reset Feb.11, DA’s SWEPCO personnel departed the staging area on the bypass near the Alliance Nathaniel Dwayne Darville, probation. Wednesday afternoon. Approximately 1,100 non-SWEPCO personnel joined SWEPCO possession of marijuana, Marquitia Jackson, simple Drake employees to provide storm assistance to both the Valley and Shreveport Districts and obstruction of justice, resist- battery, dismissed, diversion. -

A&E Network Orders Ambitious Live Daredevil Series 'The Impossible Live' from Essential Media Group Network and Producer

A&E Network Orders Ambitious Live Daredevil Series ‘The Impossible Live’ From Essential Media Group Network and Producers Also Partner with Bello Nock to Create the Special Live Event ‘Volcano Walk Live’ Documenting the Performer’s Death-Defying Untethered High-Wire Attempt Over an Active Volcano New York, NY, June 21, 2019 – A&E Network has partnered with Essential Media Group, part of KEW MEDIA GROUP INC. (“KEW MEDIA”, “KEW” or the “Company”) (TSX:KEW and KEW.WT) to produce the most ambitious live stunt series ever attempted, “The Impossible Live” (working title). In addition to this ten hour series order, A&E and Essential have also been partnering with world-renowned daredevil Bello Nock and his company Opportunity Nocks, Inc. to create “Volcano Walk Live” (working title), a live special showcasing the longest, most complicated and dangerous stunt ever attempted – a world record high-wire walk over an active volcano. The announcement was made today by Elaine Frontain Bryant, Executive Vice President and Head of Programming for A&E. “‘The Impossible Live’ will take viewers on a wild ride as they witness, in real time, the world’s greatest daredevils risking life and limb to pull off stunts worthy of a Hollywood blockbuster film, but without the benefits of retakes and CGI,” said Frontain Bryant. “The excitement of pulling off the impossible is why we have been working together with Bello, his team and Essential for the last year to continue to develop the biggest stunt of them all.” Over the course of five two-hour episodes, “The Impossible Live” (wt) will feature the world’s greatest daredevils attempting the most death-defying stunts ever seen on live television; including a parachute-less jump from a plane onto a speeding train, a motorcycle jump off a cliff in which the daredevil must drop the bike and grab on to the skids of a passing helicopter before the motorcycle plummets to the ground below; and the highest wire walk ever attempted from one hot air balloon to another. -

60 Days in Narcoland Episode Guide

60 days in narcoland episode guide Continue 60 DAYS IN: NARCOLAND is a one-hour reality show that follows six contestants as they go undercover in critical areas along I-65 - one of the largest drug trafficking corridors in the country, spanning six counties in Kentucky and Indiana - for a first-hand look at how drug cartels have infiltrated the heart of America. Secret participants came from different walks of life to address the drug crisis from different perspectives. Onlookers watch participants on the streets and at the Clark County Jail in Indiana, and travel with local law enforcement as part of the Drug Enforcement Division in an effort to get a 360-degree look at the epidemic. After the eight-episode season concludes, as well as the premiere reunion special. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Tuesday, September 24, 2019 at 10pm ET/PT, ASE premiere 60 Days in: NARCOLAND's reunion show. Starring Production and Distribution Settings Clark County Jail - Indiana USA - Kentucky USA American reality show 60 Days of InGenreReality TVStarring Jamie Noel (Seasons 1'2) Scotty Maples (Seasons 1'2) Mark Adger (Seasons 3'4) Mark Lamb (Season 5) Jonathan W. Horton (Season 6) Country Of Origin seasons6N. Episodes87 (Episodes)ProductionSy Producer (s) Gregory Henry Kimberly Woodard Jeff Grogan Production Spot (s) Jeffersonville, Indiana (Seasons 1'2) Atlanta, Georgia (Seasons 3'4) Florence, Arizona (Season 5) Gadsden, Alabama (Season 6) Installation cameraMultipleRunning time40-50 minutesProduction Company (s) Lucky 8Budget $3 million USDReleaseOriginal networkA'EPicture format480i (SDTV)1080i (HDTV)Original release10, 2016 (2016-03-10) - presentChronologyRelated showsBeyond Scared Straight, Caught Red HandedExternal Links60 Days InLucky 8 60 Days In is a television docuseries at ASE. -

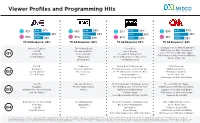

Viewer Profiles and Programming Hits

Viewer Profiles and Programming Hits 42% 18-34 27% 55% 18-34 28% 33% 18-34 28% 59% 18-34 34% 35-54 41% 35-54 39% 35-54 43% 35-54 38% 58% 45% 55-65+ 32% 55-65+ 33% 67% 55-65+ 28% 41% 55-65+ 28% TV Ad Response1 63% TV Ad Response1 60% TV Ad Response1 63% TV Ad Response1 64% America’s Top Dog The Walking Dead Below Deck The Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Live PD Two and a Half Men Project Runway CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera State of the Union With Jake Tapper Alaska PD Better Call Saul Below Deck Sailing Yacht Q1 CNN Newsroom With Fredricka Whitfield Live PD: Wanted Talking Dead The Real Housewives of New Jersey Cuomo Prime Time Breaking Bad Vanderpump Rules Live PD Tombstone Below Deck Mediterranean CNN Newsroom Biography Two and a Half Men The Real Housewives of New York City CNN Newsroom Live Q2 Live PD: Wanted Better Call Saul The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills Erin Burnett OutFront Live PD: Rewind Movies Vanderpump Rules Cuomo Prime Time Below Deck Sailing Yacht CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera Live PD Two and a Half Men The Real Housewives Of Orange County The Lead With Jake Tapper Biography Fear the Walking Dead The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills CNN Newsroom With Brooke Baldwin Q3 Garth Brooks: The Road I’m On Movies Below Deck Mediterranean Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Live PD: Wanted Southern Charm CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera The Real Housewives Of New York City Anderson Cooper 360 Garth Brooks: The Road I’m On The Walking Dead The Real Housewives of Orange County CNN Tonight With Don Lemon Court Cam Talking Dead Below Deck Mediterranean Cuomo Prime Time Q4 Live PD Movies Below Deck Anderson Cooper 360 Live PD: Wanted Project Runway Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Watch What Happens Live With Andy Cohen CNN Newsroom With Brooke Baldwin 1 Percentage of network viewers that have seen/heard a TV ad in the last 12 months that has led them to take action as defined as clicking on a banner ad, doing an internet search, going to the advertisers website, buying the product advertised or calling/visiting the advertiser. -

Today Friday Daytime April 17 Cs – Charter Spectrum Dtv – Directv D – Dish Movies Sports Kids

TVTODAY FRIDAY DAYTIME APRIL 17 CS – CHARTER SPECTRUM DTV – DIRECTV D – DISH MOVIES SPORTS KIDS . Tonight's CS DTV D 8 AM 8:30 9 AM 9:30 10 AM 10:30 11 AM 11:30 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 BROADCAST CHANNELS best bets KTLM 2 40 40 (7:00) Un nuevo dia (N) Dueños Decision Perro Noticias Noticias En CasaSuelta la sopa Al rojo vivo (N) Al Rojo Vivo (N) KGBT 4 4 4 (7:00) Morning (N) Daytime Price Right Young & R. (N) News B & B The Talk (N) Make a Deal Jeop.Jeop (N) Judy Judy KRGV 5 5 5 (7:00) GMA (N) Live The View Pandemic News (N) General Hospital Wendy Williams Feud Feud Ellen DeGeneres FOX 6 2 2 Minute Healthy H.Bench H.Bench The Real Friends Friends TMZExtra People Court (N) Kelly Clarkson The Dr. Oz Show Dateline XHAB 7 Agenda Pública Matutino Express Ciclo Festival de Gala Noticias Al Dia Onda Juvenil A Las 3 XERV 19 Al Aire Paola (N) Hoy (N) Cuéntamelo Ya!Juego Estrellas Que Pobres TanDestilando amor KTVF 20 22 Per Inq. Minute News News Today (N) Today III (N) Live Hoda - Jenna (N) Modern Mom Days. Lives (N) KVEO 8 23 23 (7:00) Today (N) Today III (N) Hoda - Jenna (N) Rachael Ray Days. Lives (N) Daily Daily Mel Robbins The Doctors Dr. Phil KLUJ 9 44 Creflo J.Hagee Osteen Intend Copelnd King FurtickR.Morris Life BetterTo Life CBD1 The 700 Club J.Hagee HopePraise KNVO 3 48 48 (7:00) Despierta America Te perdone Dios Noticier Noticier Como dice dichoMe Declaro C Univision Presen Gordo y flaca KMBH 10 60 60 Xavier Luna D.Tiger Clifford Sesame PinkaPet DinoT CatHat SesameSplashB. -

Disclaimer: Nothing Within This Page Or on This Site Overall Is the Product Of

Disclaimer: Nothing within this page or on this site overall is the product of Panagiotis Kondylis's thought and work unless it is a faithful translation of something Kondylis wrote. Any conclusions drawn from something not written by Panagiotis Kondylis (in the form of an accurate translation) cannot constitute the basis for any valid judgement or appreciation of Kondylis and his work. (This disclaimer also applies, mutatis mutandis, to any other authors and thinkers linked or otherwise referred to, on and within all of this website). EVERYBODY MUST OBEY, ABIDE BY AND FOLLOW THE LAW ALL KILLINGS AND CAUSING OF DEATH AND INJURY TO INNOCENT NON-COMBATANTS ANYWHERE IN THE WORLD ARE CONDEMNED A POSTERIORI AND A PRIORI, REGARDLESS OF WHO THE VICTIMS ARE If you read stuff written by the ABSOLUTELY CRAZED CONTINUALLY SELF- LOBOTOMISING ULTRA-LOONY MAD SATIRICAL LITERARY PERSONA (born c. 599, 699, 799, 899 or 999 A.D. in Hellenic Eastern Rome) WITHOUT HAVING READ AND STUDIED AND UNDERSTOOD ALL OF P.K.'s CORE TEXTS FIRST (AND AT THE RATE I'M CURRENTLY GOING, THAT WON'T BE POSSIBLE (UNLESS YOU KNOW GERMAN OR GREEK) BEFORE c. 2052 IF I MAKE IT THAT FAR IN AN ABLE-BODIED STATE (HIGHLY UNLIKELY, IF NOT IMPOSSIBLE)), THEN YOU ARE DOING WHAT YOU HAVE BEEN TOLD NOT TO DO, AND YOU ARE BEING RATHER NAUGHTY - TO SAY THE LEAST. I FIND, THOUGH, THAT NO-ONE EVER LISTENS TO ME, SO THEREFORE, I MUST BE WRONG. I MUST BE NO POLITICAL-IDEOLOGICAL COURSE OF ACTION IS BEING SUPPORTED OR OTHERWISE SUGGESTED BY THIS SITE EVER (THE SITE'S SATIRICAL-LITERARY PERSONA IS LITERALLY CRAZED CRAZY LOONY MAD) UNLESS IT IS SOMETHING P.K. -

APRIL 2019 Concerned Oklahomans for the Highway Patrol Society Newsletter

COHPSCOHPS APRIL 2019 Concerned Oklahomans for the Highway Patrol Society Newsletter Troopers of the Year honored at 50th Annual DPS Awards Luncheon Photos: Elise Rinta The 50th Annual Department of Public Safety Awards Luncheon took place April 9 at the Oklahoma History Center in Oklahoma City. The event was sponsored by AAA, COHPS, the Oklahoma State Troopers Association and the Retired Oklahoma Troopers Association. Numerous troopers and civilian employees were honored for outstanding performance during 2018. DPS Commissioner Rusty Rhoades said, “We would like to thank COHPS for their ongoing support of troopers and their family throughout the year, and for their role in sponsoring our annual award luncheon. We very much appreciate their contribution that helped to make this important event possible.” Pictured above left: Commissioner Rusty Rhoades, Assistant Commissioner Megan Simpson, and Chief Michael Harrell present a Trooper of the Year Award to Trp. Austin Ellis #318, honored for his actions on August 26 when he was fired upon by a fleeing suspect. Above right: Commissioner Rhoades and Chief Harrell present Trooper of the Year Awards to seven members of the OHP Tactical Team for a May 11 event in Talihina where the suspect barricaded himself in a building and engaged the team members in gunfire. For more pictures and award information, see page 2. DPS Awards 2 OSPOA; Live PD; Meyer Resolution 3 Nicholas Dees Memorial Run 4 Troop M honored 5 COHPSCOHPS Retirements, OHP Out & About 6 OHP Out & About 7-9 www.cohps.org Kudos, OHP misc. 10 501(c)(3) organization COHPS info 11 Chief’s Awards: Trp. -

Daddy Issues

Veterinary Medical Clinic September 21 - 27, 2019 William Oglesby, DVM We Treat Michael Sheen and Tom Payne Both Small co-star in “Prodigal Son” Animals and Large Animals 804 Southeast Boulevard Clinton, NC 28328 Monday-Friday 7:30am-5:30pm (910) 592-3338 Healthy Animals are Happy Animals AUTO HOME FLOOD LIFE WORK Daddy issues 101 E. Clinton St., Roseboro, N.C. 910-525-5222 [email protected] We ought to weigh well, SEE WHAT YOUR NEIGHBORS ARE TALKING ABOUT! what we can only once decide. Complete Funeral Service including: Traditional Funerals, Cremation Outdoor Power Equipment Pre-Need-Pre-Planning Independently Owned & Operated Since 1920’s Complete parts Butler Funeral Home and service department! 401 W. Roseboro Street 2 locations to Hwy. 24 Windwood Dr. Roseboro, NC better serve you Stedman, NC 401 NE Blvd., Clinton, NC • 910-592-7077 • www.clintonappliance.com 910-525-5138 910-223-7400 910-525-4337 (fax) 910-307-0353(fax) Sampson Independent — Saturday, September 21, 2019 — Page 3 Sports This Week SATURDAY 9:55 p.m. WUVC MFL Fútbol Querétaro FSS Cliff Diving (1h) 5:30 p.m. ESPN Pardon the Interruption 10:00 p.m. ESPN2 WNBA Basketball 6:00 p.m. ESPN SportsCenter (1h) at Club América. (Live) (2h05) 6:00 p.m. ESPN Baseball Tonight (Live) (30m) Playoffs. (Live) (2h) ESPN2 Around the Horn (30m) 6:00 a.m. WGN Wingshooting USA 10:00 p.m. WRDC Ring of Honor Wres- (30m) FSS N.C. State: One With Wolfpack 6:30 p.m. ESPN2 Pardon the Interrup- (30m) tling (1h) 6:30 p.m. -

Live Pd Bingo Cards

Live PD Bingo myfreebingocards.com Safety First! Before you print all your bingo cards, please print a test page to check they come out the right size and color. Your bingo cards start on Page 3 of this PDF. If your bingo cards have words then please check the spelling carefully. If you need to make any changes go to mfbc.us/e/cdqvr8 Play Once you've checked they are printing correctly, print off your bingo cards and start playing! On the next page you will find the "Bingo Caller's Card" - this is used to call the bingo and keep track of which words have been called. Your bingo cards start on Page 3. Virtual Bingo Please do not try to split this PDF into individual bingo cards to send out to players. We have tools on our site to send out links to individual bingo cards. For help go to myfreebingocards.com/virtual-bingo. Help If you're having trouble printing your bingo cards or using the bingo card generator then please go to https://myfreebingocards.com/faq where you will find solutions to most common problems. Share Pin these bingo cards on Pinterest, share on Facebook, or post this link: mfbc.us/s/cdqvr8 Edit and Create To add more words or make changes to this set of bingo cards go to mfbc.us/e/cdqvr8 Go to myfreebingocards.com/bingo-card-generator to create a new set of bingo cards. Legal The terms of use for these printable bingo cards can be found at myfreebingocards.com/terms.