Program Notes SUNDAY, JUNE 30

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Anthropology Through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-Based Sentiment

Cultural Anthropology through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-based Sentiment Peter A. Gloor, Joao Marcos, Patrick M. de Boer, Hauke Fuehres, Wei Lo, Keiichi Nemoto [email protected] MIT Center for Collective Intelligence Abstract In this paper we study the differences in historical World View between Western and Eastern cultures, represented through the English, the Chinese, Japanese, and German Wikipedia. In particular, we analyze the historical networks of the World’s leaders since the beginning of written history, comparing them in the different Wikipedias and assessing cultural chauvinism. We also identify the most influential female leaders of all times in the English, German, Spanish, and Portuguese Wikipedia. As an additional lens into the soul of a culture we compare top terms, sentiment, emotionality, and complexity of the English, Portuguese, Spanish, and German Wikinews. 1 Introduction Over the last ten years the Web has become a mirror of the real world (Gloor et al. 2009). More recently, the Web has also begun to influence the real world: Societal events such as the Arab spring and the Chilean student unrest have drawn a large part of their impetus from the Internet and online social networks. In the meantime, Wikipedia has become one of the top ten Web sites1, occasionally beating daily newspapers in the actuality of most recent news. Be it the resignation of German national soccer team captain Philipp Lahm, or the downing of Malaysian Airlines flight 17 in the Ukraine by a guided missile, the corresponding Wikipedia page is updated as soon as the actual event happened (Becker 2012. -

Literature and Film of the Weimar Republic (In English Translation) OLLI@Berkeley, Spring 2019 Mondays, April 1—29, 2019 (5 Weeks), 10:00 A.M

Instructor: Marion Gerlind, PhD (510) 430-2673 • [email protected] Literature and Film of the Weimar Republic (in English translation) OLLI@Berkeley, Spring 2019 Mondays, April 1—29, 2019 (5 weeks), 10:00 a.m. — 12:30 p.m. University Hall 41B, Berkeley, CA 94720 In this interactive seminar we shall read and reflect on literature as well as watch and discuss films of the Weimar Republic (1919–33), one of the most creative periods in German history, following the traumatic Word War I and revolutionary times. Many of the critical issues and challenges during these short 14 years are still relevant today. The Weimar Republic was not only Germany’s first democracy, but also a center of cultural experimentation, producing cutting-edge art. We’ll explore some of the most popular works: Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s musical play, The Threepenny Opera, Joseph von Sternberg’s original film The Blue Angel, Irmgard Keun’s bestseller The Artificial Silk Girl, Leontine Sagan’s classic film Girls in Uniform, Erich Maria Remarque’s antiwar novel All Quiet on the Western Front, as well as compelling poetry by Else Lasker-Schüler, Gertrud Kolmar, and Mascha Kaléko. Format This course will be conducted in English (films with English subtitles). Your active participation and preparation is highly encouraged! I recommend that you read the literature in preparation for our sessions. I shall provide weekly study questions, introduce (con)texts in short lectures and facilitate our discussions. You will have the opportunity to discuss the literature/films in small and large groups. We’ll consider authors’ biographies in the socio-historical background of their work. -

By Jeeves Music: Andrew Lloyd Webber Lyrics: Alan Ayckbourn Book: Alan Ayckbourn Premiere: Tuesday, April 22, 1975

------------------------------------------------------------------------------ By Jeeves Music: Andrew Lloyd Webber Lyrics: Alan Ayckbourn Book: Alan Ayckbourn Premiere: Tuesday, April 22, 1975 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ The Code of the Woosters BERTIE I obey the Code of the Woosters. It's a simple philosophy. When perhaps a chap's in trouble. I respond with alacrity. And if my fellow men have problems Whatever they might be They call on me The sterling Wooster B. For despite This easy nature Come the evening When battle dawns To see a Wooster Grab the livestock by both the horns For when a Wooster's mask of pleasure Becomes a steely stare You'll know he's there He'll never turn a hair What would a chap do without it? How would he get through without it? How could he stay true wihtout the Code of the Woosters? If you're at sea, I shall be there, even put off tea to be there Woosters have swum oceans for the Code of Allegiance duly owed to the Wooster Code What a load If a girl Is in the doldrums Not a paddle To her name I'll be there Though frankly speaking Womanizing's not my game But if she's really in a lather Wild eyed and hat askew He'll see her through Old you know who... Whenever it calls, can't ignore it, even give up Ascot for it Woosters have died gladly for the code of For that rugged, heavy load called the Wooster Code What a load Take my card In case you need me, if you're jousting a losing cause Like the chap Who wins the double I can rattle The natural laws So if you're eaten up with anguish I'll snatch you from its jaws No second's pause From one sincerely yours.. -

A Kitchenette Cooks up a New Solo Cabaret Show by Dan Pine Staff Writer

Friday October 7, 2005 - Thursday October 13, 2005 Thursday October 6, 2005 A Kitchenette cooks up a new solo cabaret show by dan pine staff writer Many cabaret singers cite artists like Judy Garland and Ella Fitzgerald as influences. Lua Hadar loves both, but she adds another to her personal pantheon: Lili von Shtupp, the Marlene Dietrich send-up from “Blazing Saddles.” Hadar sings the von Shtupp classic “I’m Tired” in her new solo cabaret show “It’s About Time Already,” which premieres at the Purple Onion in San Francisco on Friday, Oct. 7. She will have two other performances later this month and next month in Napa and Larkspur. Von Shtupp was played by the late Madeline Kahn in the classic 1974 Mel Brooks film, and Hadar hopes to generate the same kind of comic energy in her show that Kahn did. After all, she performs the tune with a troop of dancing Chassids, in a kind of “Fiddler”-meets-Madonna moment. Fans of Hadar’s cabaret trio The Kitchenettes already know about her sense of humor. But the new show isn’t all about laughs. In fact, the show (and an accompanying CD of the same name) was born out of personal tragedy. Hadar’s mother died last year, leaving the singer as the last living member of her original nuclear family. The resulting grief, and the growing consciousness of mortality, spurred her to create the CD and solo show. “[The show and CD are] about my coming of age emotionally in the middle third of life,” she says. -

Kadimah Yiddish Theatre 2021 SEASON PREVIEW Kadimah.Org.Au

Kadimah Yiddish Theatre 2021 SEASON PREVIEW kadimah.org.au When theatres suddenly went dark in March 2020, lightbulbs of another type switched on for us at Kadimah Yiddish Theatre. While our live shows were cancelled and you, our dear loyal audience, were stuck at home, sparks were flying in our imaginations and in our home studios. Audio books were recorded, Digital Shakespeare Monologues in Yiddish were created and live Zoom conversations were had with leading Yiddishists around the world. All through the long months of COVID-19 lockdown, the creative team has been busy writing, researching and composing a program of exciting, new and original Yiddish theatre projects that we can’t wait to share with you. As restrictions in Victoria gradually ease, our plans to present and perform these new projects are coming to life. We’ll keep you posted on dates as we know more. But in the meantime, we want to share some of the exciting ideas we’re working on - and chalishing for you to see and enjoy. Biz 2021! Galit Klas & Evelyn Krape Artistic Co-Directors, Kadimah Yiddish Theatre Durkh a Modnem Gloz Through a Strange Lens GALIT KLAS AND JOSH ABRAHAMS If you can imagine a mash-up of Laurie Anderson, Marlene Dietrich and Kraftwerk, all in Yiddish, you might come close to the breathtakingly original musical concept that is Durkh a Modnem Gloz. The brainchild of world-renowned composer Josh Abrahams and performer Galit Klas, it sets an extraordinary electronic score to lyrics based on Yiddish poetry written by women. With alternatively dreamy, cinematic, robotic techno and Eurodance style tunes, Durkh A Modnem Gloz establishes Yiddish electronic music as a genre. -

German Cinema As a Vehicle for Teaching Culture, Literature

DOCUMENT7RESUMEA f ED 239 500 FL 014 185 AUTHOR' Duncan, Annelise M. TITLE German Cinema as a Vehicle for Teaching Culture, . Literature and Histoy. 01 PUB DATE Nov 83 . NOTE Pp.; Paper presented at the Annual' Meeting of the. AmeriCan Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (San Franci co, , November 24-26, 1993), PUB TYPE Guides - Cla r om User Guides (For Teachers) (052) Speeches/Conference Papers "(150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Art Education; *Cultural Education; . *Film Study; *German; Higher Educati-on; History InStruction; Instructional Materials; Interdisciplinary Approach; *Literature Appreciation; *SeCond Language Instruction; Social HiStory ABSTRACT The use of German film in four instructional; contexts, based on experiences in developinga university course,, is aiScussed. One use is as part ofa German culture course taught in German, emphasizing the role of film as a cultural statement of ,its time, intended to be'either a social criticismor a propaganda tool.t A second use is integration of the film intoa literature course taught in German, employing a series of television' plays acquired from the Embassy of Wkst Germany. Experience with filmas part of an interdisciplinary German/journalism course offers ideas for,a third use: a curriculum, offered in Engl4sh, to explore a hi toric pdriod or film techniques. A fourth use is as an element of p riod course taught either in German or,if interdepartmental, En fish, such as a. course on t'he artistic manifestations of expres (Author/MSE) O 9- * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ** * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * 4* * ** * * * * * * * * * *********** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made '* from the original document. -

Addendum III—The Return

AODENIDUMI --------------- Addendum III The Return Gear Technology's bimonthly aberration - gear trivia, humor, weirdness and oddments for the edification and amusement of our readers. Contributions are welcome. Gears on fil'm He)'; I've Been Looking 'Of OneoHhose • PUZZLE .• PUZZLE. PUULE • PUZZLE •. It's Friday night at the video store, The Missouri State Highway and a The supply room at Wacky ~ H ~ and as usual, all the new releases are Transportation Department is trying to i Widgets Gearrnoror Company ;; checked out. You can't decide between give away the Mark Twain Memorial contains two shelves, Shelf A has III "I Killer Teenage Cheerleaders from Bridge across the Mississippi River at ... C half spur gears and half helical H Outer Space and a documentary on the Hannibal, MO, No, they're not kidding. H i= gears, Shelf B has two-thirds spur I; mating rituals of the hippopotamus. The cost [0 repair the bridge, which is : gears and one-third helical. Gear Technology is here to help. listed on the National Register of His- ! H !Every g·earmotor made by H The Addendum page is proud to pre- toric Places, is greater than the cost to H Wa.cky Widgets turns out slightly ;;; sent a list of films for gear lovers. All build a new one, so the state must try to i ~ different (that's why they're of these films feature the industry's find an alternative use for the structure ! Wacky). Their production method H own star, the late Luella Gear. before it can tear it down, e H Born in 1900 in New York, Gear More than 100 proposals were sub- Do ls to blindfold the foreman, spin Iii made her broadway debut in 1917. -

PRESS RELEASE for IMMEDIATE RELEASE DATE: 15 June 2016

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DATE: 15 June 2016 HK Phil Season Finale with Ashkenazy and Behzod (1 & 2 July) Great pianists of two generations on stage for Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto no. 3 [15 June 2016, Hong Kong] Vladimir Ashkenazy has long been considered one of the great pianists of our time, and his career as a conductor has left audiences no less enthralled. In July, he returns to close the season of the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra (HK Phil) with Elgar’s noble first Symphony. This concert combines his musical mastery with the talents of phenomenal young pianist Behzod Abduraimov who returns to Hong Kong by popular demand, this time to perform Prokofiev’s dazzling and hugely exciting Piano Concerto no. 3. Prokofiev clearly had a particular affection for his Piano Concerto no. 3, as it was the only one of his five piano concertos which he recorded. The concerto was ecstatically received by American audiences at its premiere, and, has become a mainstay of the piano repertoire. Its dynamism, rhythmic intensity and technical bravura are unfailingly thrilling. Between Abduraimov, with his amazing technique and musicianship, and Ashkenazy with his understanding of the work as both pianist and conductor, Hong Kong audiences are in for a rare treat. In the second half of the concert, Ashkenazy will lead the orchestra in Elgar’s Symphony no. 1. Elgar’s music is characterised by the instruction ‘nobilmente’, and is indeed the definition of noble. He dedicated it to Hans Richter, the Austro-Hungarian conductor who directed the work’s triumphant premiere, and who declared it “the greatest symphony of modern times”. -

Behzod Abduraimov Piano

Behzod Abduraimov Piano “Abduraimov can do anything. His secret: authenticity, control and a velvet pianissimo.” (NRC Handelsblad). Behzod Abduraimov’s performances combine an immense depth of musicality with phenomenal technique and breath-taking delicacy. He works with leading orchestras worldwide including the Los Angeles Philharmonic, London Symphony Orchestra, NHK Symphony Orchestra and Münchner Philharmoniker, and prestigious conductors including Valery Gergiev, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Manfred Honeck, Lorenzo Viotti, Vasily Petrenko, James Gaffigan, Jakub Hrůša and Vladimir Jurowski. Forthcoming European engagements include Orchestre de Paris, Leipzig Gewandhaus, Luzerner Sinfonieorchester - including a tour to the Tongyeong International Music Festival under Michael Sanderling - English Chamber Orchestra, and St Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra with performances in St Petersburg and Barcelona. He will also be presented in recital at the Kölner Philharmonie, Festspielhaus Baden-Baden and returns to the Verbier and Rheingau festivals. Behzod has recently worked with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, BBC Symphony, hr-Sinfonieorchester, BBC Scottish Symphony and Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra. In May 2018, he was Artist in Residence at the Zaubersee Festival in Lucerne, which included a performance of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No.2 as well as a number of chamber recitals. He has also performed at Lucerne and Kissinger Sommer Festivals. Last season recital highlights included the Concertgebouw Amsterdam, Barbican Hall London and Prinzregententheater in Munich. Behzod continues his collaboration with Truls Mørk following their highly successful tours last season with forthcoming recitals including Wigmore Hall and Washington DC. In North America, Behzod returns to both the Pittsburgh and Seattle symphonies and will be presented in recital at Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 92nd Street Y, Maestro Foundation and Vancouver Recital Series amongst others. -

BOOK REVIEWS 361 Artists in Exile

BOOK REVIEWS 361 Artists in Exile: How Refugees from Twentieth-Century War and Revolution Transformed the American Performing Arts. By Joseph Horowitz. (New York: HarperCollins, 2008. Pp. xix, 458. Illustra- tions. $27.50.) Joseph Horowitz, formerly a music critic for the New York Times and prolific author of valued books about music and musicians in the United States, has now expanded his scope of interests to include the American blend of classical ballet with modern dance (most notably through George Balanchine); Hollywood films directed by such emigr´ es´ as Josef von Sternberg and Ernst Lubitsch with glamorous stars like Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo; serious theater and Broadway musicals (directed by the likes of Rouben Mamoulian and scenes designed by the brilliant Boris Aronson); along with composers and conductors ranging from George Szell to Leopold Stokowski (Garbo’s sometime traveling companion). It’s a very full and rich menu, organized biographically within those topical categories, with a few writers (Thomas Mann and Vladimir Nabokov) thrown in rather cursorily at the end. The author states his purpose near the outset: “how during the first half of the twentieth century immigrants in the performing arts impacted American culture—and how, as part of the same process of transference and exchange, the United States impacted upon them” (p. 8). The book reads well despite the repeated use of “impacted” as an active verb (federalese lapsing into common usage, alas) and a few spots where syntax and phrasing seem oddly off-key. Preparing the book required prodigious research: examining many musical scores and listening to numerous recorded performances; watching countless films, many of them obscure; reading raft- loads of biographies and theater criticism; and looking at numer- ous manuscript collections. -

Clothes Make the (Wo)Man: Marlene Dietrich and “Double Drag”

Kennison, Rebecca (2002) “Clothes Make the (Wo)man,” Journal of Lesbian Studies, 6:2, 147–156. DOI: 10.1300/J155v06n02_19 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J155v06n02_19 Clothes Make the (Wo)man: Marlene Dietrich and “Double Drag” Rebecca Kennison SUMMARY. Dietrich, like Madonna, has been called gender‐bending and androgynous, but Dietrich’s on‐ and off‐screen fluidity of gender identity, as reflected in her adoption of the “double drag,” upsets the traditional dichotomy encoded more generally as that of male or female and more particularly as that of the butch or femme. KEYWORDS. Dietrich, drag, gender roles, performance, subversion She steps out on stage to sing, dressed in a man’s suit, short blond hair brushed back from her face, legs apart, one hand on her hip, the other holding a monocle to her eye—for all the male garb, very much a woman. She looks into the camera— provocatively, seductively, erotically. Madonna on her 1990 Blond Ambition tour? Or Marlene Dietrich, who defined blond ambition 60 years earlier? Although it is Madonna who has been called “the virtual embodiment of Judith Butler’s arguments in Gender Trouble” (Mistry) on the fluidity of gender roles and the subversiveness of drag, Dietrich performed that role well before Gender Trouble was ever written—or Madonna even born. In fact, through Dietrich’s appropriation of gay male and lesbian fashion, combined with a femme sensibility, her on‐ and off‐screen fluidity of gender identity upsets the dichotomy and tautology of the roles encoded by traditional gender identification as either male or female, as well as that of the traditional lesbian terminology of butch or femme. -

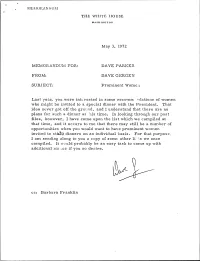

Dave Gergen to Dave Parker Re

MEf\IOR/\NIHJM THE WHITE HOUSE WASIIINGTON May 3, 1972 MEMORANDUM FOR: DAVE PARKER FROM: DAVE GERGEN SUBJECT: Prominent Wome~l Last year, you were int( rested in some recomrrj "c1ations of women who might be invited to a special dinner with the President. That idea never got off the ground, and I understand that there are no plans for such a dinner at :lis time. In looking through our past files, however, I have come upon the list which we compiled at that time, and it occurs to me that there Inay still be a number of opportunities when you would want to have prominent wom.en invited to st~~ dinners on an individual basis. For that purpose: I am sending along to you a copy of some other li i~S we once compiled. It would probably be an easy task to come up with additional nm, ~cs if you so desire. cc: Barbara Franklin r-------------------------------------------------------------- Acaflemic Hanna Arendt - Politic'al Scientist/Historian Ar iel Durant - Histor ian Gertrude Leighton - Due to pub lish a sem.ina 1 work on psychiatry and law, Bryn Mawr Katherine McBride - Retired Bryn Mawr President Business Buff Chandler - Business executive and arts patron Sylvia Porter - Syndicated financial colun1.nist Entertainment Mar ian And ",r son l Jacqueline I.. upre - British cellist Joan Gan? Cooney - President, Children1s Television Workshop; Ex(,cutive Producer of Sesaxne St., recently awarded honorary degre' fron'l Oberlin Agnes DeMille - Dance Ella Fitzgerald Margot Fonteyn - Ballerina Martha Graham. - Dance Melissa Hayden - Ballerina Helen Hayes Katherine Hepburn Jv1ahilia Jackson Mary Martin 11ary Tyler Moore Leontyne Price Martha Raye B(~verley Sills - Has appeared at "\V1-I G overnmcnt /Politics ,'.