PPG Industries, Inc. V. Tracy (1996), _____ Ohio St.3D _____.]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Carlisle ELECTRICAL & WIRING TREASURED MOTORCAR SERVICES RED BEARDS TOOLS Events App for Iphone and L 195-198, M 196-199 Android

OFFICIAL EVENT GUIDE Contents WORLD’S FINEST CAR SHOWS & AUTOMOTIVE EVENTS 5 WELCOME 7 FORD MOTOR COMPANY 9 SPECIAL GUESTS 10 EVENT HIGHLIGHTS 15 WOMEN’S OASIS 2019-2020 EVENT SCHEDULE 17 NPD SHOWFIELD HIGHLIGHTS JAN. 18-20, 2019 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAYS: AUTO MANIA 19 FORD GT PROTOTYPE ALLENTOWN PA FAIRGROUNDS JAN. 17-19, 2020 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: FEB. 22-24, 2019 21 FORD NATIONALS SELECT WINTER AUTOFEST LAKELAND SUN ’n FUN, LAKELAND, FL FEB. 21-23, 2020 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: 22 40 YEARS OF THE FOX BODY LAKELAND WINTER FEB. 22-23, 2019 COLLECTOR CAR AUCTION FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: SUN ’n FUN, LAKELAND, FL FEB. 21-22, 2020 25 50 YEARS OF THE MACH 1 APRIL 24-28, 2019 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: SPRING CARLISLE CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS 26 50 YEARS OF THE BOSS APRIL 22-26, 2020 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: SPRING CARLISLE APRIL 25-26, 2019 29 50 YEARS OF THE ELIMINATOR COLLECTOR CAR AUCTION CARLISLE EXPO CENTER APRIL 23-24, 2020 29 SOCIAL STOPS IMPORT & PERFORMANCE MAY 17-19, 2019 EVENT MAP NATIONALS 20 CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS MAY 15-17, 2020 19 EVENT SCHEDULE FORD NATIONALS MAY 31-JUNE 2, 2019 PRESENTED BY MEGUIAR’S 34 GUEST SPOTLIGHT CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS JUNE 5-7, 2020 37 SUMMER OF ’69 CHEVROLET NATIONALS JUNE 21-22, 2019 CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS 39 VENDORS: BY SPECIALTY JUNE 26-27, 2020 CARLISLE AUCTIONS JUNE 22, 2019 43 VENDORS: A-Z SUMMER SALE CARLISLE EXPO CENTER JUNE 27, 2020 48 ABOUT OUR PARTNERS JULY 12-14, 2019 CARLISLE FAIRGROUNDS CHRYSLER NATIONALS 51 POLICIES & INFORMATION CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS JULY 10-12, 2020 53 CONCESSIONS TRUCK NATIONALS AUG. -

Kindle / Ford Mustang ^ Read

NA1JRKPM3D Ford Mustang > Book Ford Mustang By - Reference Series Books LLC Jan 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 249x189x10 mm. This item is printed on demand - Print on Demand Titel. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 57. Chapters: Ford Mustang variants, Shelby Mustang, Bullitt, Ford Mustang SVT Cobra, Ford Mustang Mach 1, Ford Mustang SSP, Boss 302 Mustang, California Special Mustang, Ford Mustang I, Eleanor, Ford Mustang SVO, Ford Mustang FR500, Boss 429, Giugiaro Ford Mustang. Excerpt: The first- generation Ford Mustang is the original pony car, manufactured by Ford Motor Company from 1964 until 1973. Initially introduced as a hardtop and convertible, with the fastback version put on sale following year. At the time of its introduction the Mustang, sharing its underpinnings with Falcon, was slotted into a compact car segment. With each revision the Mustang saw an increase in overall dimensions and in engine power. As a result, by 1971 the Mustang had entered the muscle car segment. After an initial surge, sales were steadily declining and Ford began working on a new generation Mustang. When the oil crisis hit in 1973 Ford was prepared, having already designed the smaller Mustang II. This car had no common components with preceding models. As Lee Iacocca's assistant general... READ ONLINE [ 1.66 MB ] Reviews Complete information for publication fans. Better then never, though i am quite late in start reading this one. Its been written in an extremely straightforward way in fact it is just soon after i finished reading this ebook in which basically altered me, change the way i believe. -

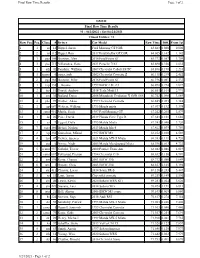

DMVR Final Raw Time Results #1 - 04242021 - Sat 04-24-2021 Timed Entries: 73 Raw Pos

Final Raw Time Results Page 1 of 2 DMVR Final Raw Time Results #1 - 04242021 - Sat 04-24-2021 Timed Entries: 73 Raw Pos. Pos. Class # Driver Car Model Raw Time Diff. From 1st 1 1 ss 12 Rippel, Jason Ford Mustang GT350R 63.663 0.000 0.000 2 2 ss 112 Rippel, Ron 2017 Ford Shelby GT350R 64.805 1.142 1.142 3 1 pgs 106 Bronson, Alex 2016 Ford Focus ST 65.372 0.567 1.709 4 3 pas 711 Villanueva, Hans 2021 Porsche 718T 65.698 0.326 2.035 5 1 sth 42 Fanchier, William 2009 Chevrolet Cobalt SS/TC 65.896 0.198 2.233 6 3 tcams 0 jones, josh 2002 Chevrolet Corvette Z 66.115 0.219 2.452 7 2 pgs 160 Bronson, Mike 2016 Ford Focus ST 66.196 0.081 2.533 8 1 txp 138 .., Boonie 1999 BMW 2.8L Z3 66.490 0.294 2.827 9 2 tss 61 Dostal, Andrew 2018 Tesla Model 3 66.654 0.164 2.991 10 1 sm 30 Ballard, Darin 2008 Mitsubishi Evolution X GSR SSS 66.752 0.098 3.089 11 4 pbs 99 Walker, Adam 1997 Chevrolet Corvette 66.845 0.093 3.182 12 1 xp 687 Watters, William 1996 Mazda miata 67.037 0.192 3.374 13 1 camt 916 Mattis, Scott 1987 Ford Mustang GT 67.242 0.205 3.579 14 1 ds 26 Price, David 2019 Honda Civic Type R 67.343 0.101 3.680 15 1 es 9 Eggert, Dave 1995 Mazda Miata 67.383 0.040 3.720 16 7 txsa 180 Bickel, Nathan 2013 Mazda Mx-5 67.422 0.039 3.759 17 2 xp 350 Gustafson, Mikael 1997 BMW M3 68.252 0.830 4.589 18 4 tcs 47 Dewey, Spencer 2021 Mazda MX-5 Miata 68.383 0.131 4.720 19 1 stu 6 Nimry, Nadir 2005 Mazda Mazdaspeed Miata 68.396 0.013 4.733 20 5 tcamt 957 Seibold, Trevor 2000 Pontiac Trans Am 68.482 0.086 4.819 21 2 camt 667 Folkestad, Preston 1984 Chevrolet C10 -

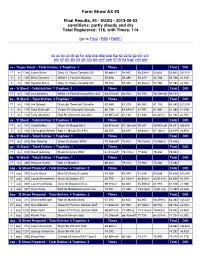

Final Results, #3 - SUSQ - 2013-06-02 Conditions: Partly Cloudy and Dry Total Registered: 116, with Times: 114

Farm Show AX #3 Final Results, #3 - SUSQ - 2013-06-02 conditions: partly cloudy and dry Total Registered: 116, with Times: 114 [go to Final | PAX | RAW ] ss as bs cs ds gs hs asp bsp dsp esp fsp xp cp fp gp bm cm em stf stc sts str stx stu sm smf ssm rtf rtr rta bspl cml sml ss - 'Super Stock' - Total Entries: 3 Trophies: 1 Times Total Diff. 1T ss 1106 Jason Burns Grey 10 Chevy Corvette GS 56.886+1 54.567 55.534+1 53.823 53.823 [-]0.913 2 ss 122 Brian Conners White 11 Porsche Boxstor 55.606 55.369 55.122 54.736 54.736 +0.913 3 ss 106 Heather Burns Grey 10 Chevy Corvette GS 59.722 59.395 60.503+1 57.785 57.785 +3.049 as - 'A Stock' - Total Entries: 1 Trophies: 1 Times Total Diff. 1T as 116 Lisa Leathery White 13 Ford Mustang Boss 302 64.072+off 84.703 69.755 58.739+off 69.755 - bs - 'B Stock' - Total Entries: 3 Trophies: 1 Times Total Diff. 1T bs 109 Jim Bobeck Black 89 Chevrolet Corvette 62.999 61.078 60.062 61.124 60.062 [-]1.018 2 bs 119 Cord Kisthardt Yellow 91 Chevrolet Corvette 66.728 64.594+1 61.787 61.080 61.080 +1.018 3 bs 114 Tony Sklareski Red 90 Chevrolet Corvette 62.967+off 61.132 61.430 64.421+1 61.132 +0.052 cs - 'C Stock' - Total Entries: 2 Trophies: 1 Times Total Diff. -

Final Results

Farm Show AX #11 - SUSQ SCCA - 2013-09-15 PM conditions: sunny & warm all day Total Registered: 89, with Times: 89 [go to Final | PAX | RAW ] ss as bs cs es hs ssp bsp csp dsp esp fsp xp cp fp gp am bm em fm stc sts str stx stu sm smf ssm rtf rtr rta hsl ss - 'Super Stock' - Total Entries: 3 Trophies: 1 Times Total Diff. Silver 02 Chevrolet 1T ss 308 Ryan Palmer 54.081 53.155 54.866+1 59.198+3 53.155 - Z06 Richard Black 02 Chevy 2 ss 314 65.378 64.550 67.024 66.352+1 64.550 +11.395 Puerzer Corvette Andrew Black 02 Chevy 3 ss 1314 68.740 67.311 64.662 65.092 64.662 +0.112 Puerzer Corvette as - 'A Stock' - Total Entries: 1 Trophies: 1 Times Total Diff. White 13 Ford Boss 1T as 324 Lisa Leathery 66.130 62.176 60.554 60.013 60.013 - Mustang bs - 'B Stock' - Total Entries: 2 Trophies: 1 Times Total Diff. Red 90 Chevrolet 1T bs 1312 Kyle Sklareski 54.672 55.508 54.495 56.564+1 54.495 [-]0.839 Corvette Red 90 Chevrolet 2 bs 312 Tony Sklareski 57.104 55.522 55.924 55.334 55.334 +0.839 Corvette cs - 'C Stock' - Total Entries: 1 Trophies: 1 Times Total Diff. 1T cs 301 Chad Kettler Silver 10 Mazda Mx-5 55.376 55.790 59.859+2 55.191 55.191 - es - 'E Stock' - Total Entries: 2 Trophies: 1 Times Total Diff. -

Special Thanks...Revell Inc Thanks the Following Licensors For

Special Thanks... Revell Inc thanks the following licensors for their cooperation and support: Acme Trading Co. D&M – Dave Glass IMG/VW Northrop Grumman Systems Corporation Street Fighter is a registered trademark Daimler Trucks North America, LLC K.S. Pittman A-7A Corsair II®, A-10 Thunderbolt®, and used with permission from Acme ™ ™ Dave Deal Jim Wangers Production A-10 Warthog , A-6E , F4U-4 Trading Co. ® ™ Dave Deal name and designs used Jim Wanger name, likeness, vehicle Corsair , F6F Hellcat , F-14A ™ ™ AM General LLC. under license designs used under license Tomcat , F-14D Super Tomcat , F-84G HUMVEE®, the HUMVEE® design Thunderjet™, OS2U Kingfisher™, P-47D and the HUMVEE® trade dress are Ed Roth Joel Rosen-Baldwin Motion Thunderbolt®, P-47N Thunderbolt®, trademarks of AM General, LLC and are Feld Motor Sports, Inc. Lamborghini P-61 Black Widow® are trademarks used under license. All Rights Reserved. Monster Jam® and Grave Digger® are The trademarks, copyrights and of Northrop Grumman Systems AUDI AG trademarks used under license by Feld design rights in and associated with Corporation and is are used under Trademarks, design patents and Motor Sports, Inc. All rights reserved. the following Lamborghini vehicle license to Revell Inc. Diablo, Countach and Murciélago are copyrights are used with the approval of Ferrari S.p.A PACCAR Inc the owner AUDI AG. Produced under license of Ferrari Spa, used under license from Automobili Lamborghini S.p.A, Italy. Porsche AG BMW FERRARI, the PRANCING HORSE device, Porsche, the Porsche shield and the The MINI logo and the MINI wordmark all associated logos and distinctive Lockheed Martin Corporation ® ® distinctive design of Porsche cars are trademarks of BMW AG and are designs are property of Ferrari Spa. -

CAM Challenge Entrant List W Work Assignments

Class List 2021 Tire Rack SCCA Peru CAM Challenge 08/06/2021 - 08/08/2021 www.ProntoTimingSystem.com Nbr Driver's name, Hometow Car, Sponsor Tire Mfg Region, Division Work Assign CkIn Index Classic American Muscle Category Classic American Muscle Spo (CAMS) Drivers: 32 193 Kevin Keys 2000 Chevrolet Corvette NavyBlue BFGoodrich Indianapolis event tech [93] Huntington, IN ConeHub 06/07/2021 19:12:08 Great Lakes 474651 99 Steve Waters 2017 Chevrolet Corvette White Yokohama Atlanta Safety [199] Smyrna, GA 06/10/2021 12:45:15 Southeast 242533 177 Dan Doroff 2008 Chevrolet Corvette Blue Falken Land O Lakes Corner 2 [77] Shoreview, MN 06/11/2021 17:44:15 Great Lakes 555767 71 Dave Baird 2006 Pontiac Solstice Red Yokohama South Bend Corner 4 [171] Lowell, MI Dave Baird 06/13/2021 21:43:48 Great Lakes 489638 75 Les Schober 2002 Chevrolet Corvette Blue Yokohama Indianapolis set up Fenton, MI Applegate Racing 06/15/2021 13:51:55 Midwest 242043 81 Robert Armstrong 2007 Chevrolet C6Z Blk Yokohama Cincinnati Grid [81] Monroe, OH ART 06/18/2021 04:15:31 Great Lakes 450912 45 Eric Peachey 2007 Chevrolet Corvette Z06 Red BFGoodrich Susquehanna Solo Matters [145] Manheim, PA 06/23/2021 15:16:13 Northeast 487714 145 Justin Peachey 2007 Chevrolet Corvette Z06 Red/Wh BFGoodrich Susquehanna Corner 2 Radio [45] Manheim, Pa Stranoparts/Borg Motorsports/Hawk Performan 06/23/2021 21:18:17 Northeast 500954 38 Bill Hughes 2003 Chevrolet Z06 Red Yokohama Western Ohio Corner 2 Kettering oh, OH 06/27/2021 23:34:31 Great Lakes 204608 42 Christopher Scafero 2002 Chevrolet -

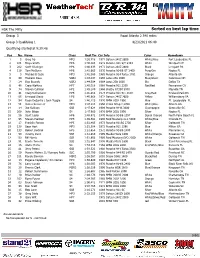

Sorted on Best Lap Time Group 3 Road Atlanta 2.540 Miles Group 3 Qualifying 1 4/23/2021 06:40 Qualifying Started at 9:39:46

HSR The Mitty Sorted on best lap time Group 3 Road Atlanta 2.540 miles Group 3 Qualifying 1 4/23/2021 06:40 Qualifying started at 9:39:46 Pos No. Name Class Best Tm Car Info Color Hometown 1 5 Greg Ira MP3 1:36.718 1971 Datsun 240Z 2800 White/Blue Fort Lauderdale FL 2 101 Mayo Smith HP6 1:40.083 1972 Porsche 911 S/T 2464 White Westport CT 3 202 Scott Kissinger HP6 1:40.633 1971 Datsun 240Z 2800 Black Leesport PA 4 118 Tom McGlynn HP6 1:41.665 1970 Porsche 914/6 GT 2400 Purp/Grn Naples FL 5 3 Michael B Cobb MP3 1:42.360 1985 Porsche 924 Turbo 1781 Orange Atlanta GA 6 69 Malcolm Ross VSR2 1:43.047 1965 Lotus 23b 1600 Blue/Silver Columbus OH 7 24 Doc Buundy VSR2 1:44.504 1964 Lotus 23b 1600 Blu Dallas TX 8 46 Craig Watkins HP7 1:45.018 1968 Porsche 911 2200 Tan/Red Penngrove CA 9 74 Steven Cullman HP2 1:45.180 1966 Shelby GT350 5000 Mayville TN 10 41 Craig Sutherland HP6 1:45.254 1973 Porsche 911 S/T 2500 Grey/Red Roeland Park KS 11 85 Linwood Staub HP6 1:45.868 1972 Datsun 240Z 2800 Yellow Williamsburg VA 12 94 Dean DeSantis / Josh Tuggle S4 1:46.213 1976 BMW 2002 1990 Blue Ft. Lauderdale FL 13 51 James Reeves Jr MP3 1:47.113 1966 Yenko Stinger 2700 White/Blue Atlanta GA 14 14 Joe Sullivan SSB 1:47.624 1989 Porsche 944S 3000 Champagne Greenville SC 15 208 John Bibbo S4 1:47.960 1976 BMW 2002 1995 Silver Naples FL 16 56 Scott Leder HP6 1:48.972 1970 Porsche 914/6 2397 Signal Orange North Palm Beach FL 17 95 Steven Piantieri HP5 1:49.562 1965 Ford Mustang 2+2 5000 White/Blue Orlando FL 18 17 Franklin Farrow HP5 1:51.405 1973 Porsche 911RS -

Production Car Classes & SPA Schedule

6. Point Assessment Schedule 6.1 The point assessment schedule will be used to place a vehicle into the proper category when any modifications are made to the vehicle. Any addition of a kit/system will be assessed an SPA for each individual component/part added. “Bumping” of a vehicle will occur when certain modifications are judged to offer a competitive advantage over other vehicles in the prescribed category. Points are assessed at technical inspection for such modifications. The addition of modification points, including Stock Assessment Points (SAP) within the Midwestern Council Autocross Classification List, if any, is used to determine when a vehicle is to be bumped to a higher category: Point Assessment Schedule Total Points Category 0-2 Stays in Stock Category 3-9 Bump to Prepared Category 10-22 Bump to Modified Category 23 and over Move to Race or Street Tire Class 6.2 Dealer-installed options that are not available from the factory are considered vehicle modifications from the base model. The modifications should be assessed appropriate points as listed in Section 6.3. 6.3 Points will be assessed at tech as follows: Tires, Wheels, and Suspension Adjustable non-factory air spring 4 Coil-over addition or kit (additional camber adjustability is allowed) 4 Tires with a wear rating less than 140 3 Change of rim width, per full inch increment of increase over stock 1 Suspension bushing replacement, excluding sway bars and shock absorbers 1 Sway bar revision or addition: Front=1; Rear=1 1,1 Change of spring rate (including modification of stock springs, i.e. -

Secondary Controls in Domestic 1986 Model Year Cars Paul Green Don Ottens Sue Adams

UMTRI-87-21 Secondary Controls in Domestic 1986 Model Year Cars Paul Green Don Ottens Sue Adams October 1987 The University of Michigan UMTRI Transportation Research Institute Tuhaical Roport Documontation Page 1. R-rt No. 2. Govemmt Accession No. 3. Rocipimt's Cotolog No. UMTRI-87-21 4. Title ad Subtitle 5. Rmport Dote October, 1987 SECONDARY CONTROLS IN DOMESTIC 1986 MODEL 6. Pwforning Orgottirotion Cod. YEAR CARS 389036 8. PwhingOr9onixation Report NO. 7. Auhdal P. Green, D. Ottens, and S. Adams UMTRI-87-21 9. Perkming Orgmimtion Nme md Addreas 10. Work Unit No. The University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute 11. bntroct O, Grant NO. 2901 Baxter Road DRDA-85-2382-P1 , Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2150 U.S.A. 13. TIP. of Rwand Period Corerod 12. +swing Ag.ncy NN adAddress Interim Chrysler Motors Corporation 9/1/85 - 8/31/87 R&D Programs Administration 12000 Chrysler Drive 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Highland Park, MI 48288-1118 2000512 IS. Svwlmntry NOHI Supported by the Chrysler Challenge Fund 1'6. Abstroct This report describes a survey of 1986 model year domestic and imported cars. A total of 236 cars were examined, representing 90% of the cars domestically produced or imported to the United States for that model year. The data were collected by visiting car dealerships and surveying all models and body styles (i.e., 2-door, 4-door, station wagons, etc.). For each car surveyed, 31 secondary controls (e.g., front wiper, turn signal, dome light, etc.) were examined in order to answer the following questions: - Where were the switches for these controls located? - What kind of switches were used for each control? - What motions were used to operate these controls? - How were the switches labeled? - Were there any patterns in switch location or design by manufacturer? The report contains a large number of tables and figures that answer these questions. -

The Ford Mustang SVO

OFFICIAL MONTHLY PUBLICATION OF CENTRAL VALLEY MUSTANG CLUB February 2017 The Ford Mustang SVO A Turbocharged Ponycar Pioneer Find us on John Wick’s ’69 Mustang Visit Our Website Fastback Is Back www.cvmustang.org WEBMASTER Paul Beckley 323-7267 Central Valley Mustang Club, Inc. NEWSLETTER EDITOR Garo Chekerdemian 906-7563 Website: http://www.cvmustang.org ADVERTISING Talk to a Member at Large Club Purpose: To provide a common meeting ground for Mustang ADVERTISING RATES: owners and further the enjoyment of ownership; to include workshops, discussions and technical meetings; to promote a more favorable relationship with the general motoring public; to further the Classified Ads (3 Lines) preservation and restoration of all Mustangs. CVMC Members FREE Non Members per issue $3.00 Who Can Join: The club is open to all Mustang enthusiasts. Any with Photo $10.00 individual or family can join. Ownership of a Mustang is not essential, but enthusiasm is. CVMC embraces the practice of encouraging Business Card Ad diversity within the membership and involvement of the entire family in CVMC Members FREE its membership and at all club events. Issue $5.00 Six Months $13.00 A Family Oriented Organization: As a part of promoting family One Year $25.00 involvement in the club, children are allowed and in fact encouraged at all club functions. In deference to this family involvement and the driving of motor vehicles, consumption of alcoholic beverages is Double Business Card Ad (1/4 Page) discouraged at club events except where the club is staying Issue $7.00 overnight and there is no potential for any drinking member or guest Six Months $20.00 to get behind the wheel. -

Applications Ford Cougar Base V6 3.8L Ford Fairmont Base V8 5.0L Ford

TECHNICAL SUPPORT 888-910-8888 94621 CORE MATERIAL TANK MATERIAL Aluminum Aluminum HEIGHT WIDTH 7-3/4 In. 6 In. THICKNESS INLET 2 In. 5/8 In. OUTLET 3/4 In. Applications Ford Cougar Base V6 3.8L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1986 GAS CARB N 3 - 1985 GAS CARB N 3 - Ford Fairmont Base V8 5.0L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1983 GAS CARB N F - 1982 GAS CARB N F - 1981 GAS CARB N F - 1980 GAS CARB N F - 1979 GAS CARB N F - Ford Fairmont Base L4 2.3L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1982 GAS CARB N A - 1981 GAS CARB N A - 1980 GAS CARB N A - 1979 GAS CARB N Y - Ford Fairmont Base L6 3.3L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1982 GAS CARB N B - 1981 GAS CARB N B - 1980 GAS CARB N B - 1979 GAS CARB N T - Ford Fairmont Base V8 4.2L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1982 GAS CARB N D - 1981 GAS CARB N D - 1980 GAS CARB N D - Ford Fairmont Elite V8 5.0L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1983 GAS CARB N F - 1982 GAS CARB N F - 1981 GAS CARB N F - 1980 GAS CARB N F - 1979 GAS CARB N F - Ford Fairmont Futura L4 2.3L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1983 GAS CARB N A - 1982 GAS CARB N A - 1981 GAS CARB N A - 1980 GAS CARB N A - 1979 GAS CARB N Y - Ford Fairmont Futura L6 3.3L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP.