Viennese Memories of History and Horrors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: August 6th, 2007 I, __________________Julia K. Baker,__________ _____ hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in: German Studies It is entitled: The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life-Writing and Documentary Film This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Katharina Gerstenberger Dr. Sara Friedrichsmeyer Dr. Todd Herzog The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life-Writing and Documentary Film A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) In the Department of German Studies Of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julia K. Baker M.A., Bowling Green State University, 2000 M.A., Karl Franzens University, Graz, Austria, 1998 Committee Chair: Katharina Gerstenberger ABSTRACT “The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life- Writing and Documentary Film” is a study of the literary responses of writers who were Jewish children in hiding and exile during World War II and of documentary films on the topic of refugee children and children in exile. The goal of this dissertation is to investigate the relationships between trauma, memory, fantasy and narrative in a close reading/viewing of different forms of Jewish life-writing and documentary film by means of a scientifically informed approach to childhood trauma. Chapter 1 discusses the reception of Binjamin Wilkomirski’s Fragments (1994), which was hailed as a paradigmatic traumatic narrative written by a child survivor before it was discovered to be a fictional text based on the author’s invented Jewish life-story. -

The Vienna Children and Youth Strategy 2020 – 2025 Publishing Details Editorial

The Vienna Children and Youth Strategy 2020 – 2025 Publishing Details Editorial Owner and publisher: In 2019, the City of Vienna introduced in society. Thus, their feedback was Vienna City Administration the Werkstadt Junges Wien project, a taken very seriously and provided the unique large-scale participation pro- basis for the definition of nine goals Project coordinators: cess to develop a strategy for children under the Children and Youth Stra- Bettina Schwarzmayr and Alexandra Beweis and young people with the aim of tegy. Now, Vienna is for the first time Management team of the Werkstadt Junges Wien project at the Municipal Department for Education and Youth giving more room to the requirements bundling efforts from all policy areas, in cooperation with wienXtra, a young city programme promoting children, young people and families of Vienna’s young residents. The departments and enterprises of the “assignment” given to the children city and is aligning them behind the Contents: and young people participating in shared vision of making the City of The contents were drafted on the basis of the wishes, ideas and concerns of more than 22,500 children and young the project was to perform a “service Vienna a better place for all children people in consultation with staff of the Vienna City Administration, its associated organisations and enterprises check” on the City of Vienna: What and young people who live in the city. and other experts as members of the theme management groups in the period from April 2019 to December 2019; is working well? What is not working responsible for the content: Karl Ceplak, Head of Youth Department of the Province of Vienna well? Which improvements do they The following strategic plan presents suggest? The young participants were the results of the Werkstadt Junges Design and layout: entirely free to choose the issues they Wien project and outlines the goals Die Mühle - Visual Studio wanted to address. -

Federation to Hold “Conversation with Michael Oren” on Nov. 30

November 6-19, 2020 Published by the Jewish Federation of Greater Binghamton Volume XLIX, Number 36 BINGHAMTON, NEW YORK Federation to hold “Conversation with Michael Oren” on Nov. 30 By Reporter staff said Shelley Hubal, executive “delightful.” Liel Leibovitz, an Oren served as Israel’s ambassador to The Jewish Federation of Greater Bing- director of the Federation. “I Israeli-American journalist and the United States for almost five years hamton will hold a virtual “Conversation look forward to learning how author, wrote that “Oren delivers before becoming a member of Knesset and with Michael Oren” about his new book of he came to write the many sto- a heartfelt and heartbreaking deputy minister in the Prime Minister’s short stories, “The Night Archer and Other ries that appear in his book. I account of who we are as a spe- Office. Oren is a graduate of Princeton Stories,” on Monday, November 30, at would also like to thank Rabbi cies – flawed, fearful, and lonely and Columbia universities. He has been noon. Dora Polachek, associate professor of Barbara Goldman-Wartell for but always open-hearted, always a visiting professor at Harvard, Yale and romance languages and literatures at Bing- alerting us to this opportunity.” trusting that transcendence is Georgetown universities. In addition to hamton University, will moderate. There is Best-selling author Daniel possible, if not imminent.” (For holding four honorary doctorates, he was no cost for the event, but pre-registration Silva called “The Night Archer The Reporter’s review of the awarded the Statesman of the Year Medal is required and can be made at the Feder- and Other Stories” “an extraor- book, see page 4.) by the Washington Institute for Near East ation website, www.jfgb.org. -

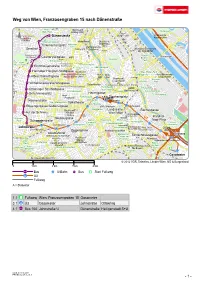

Footpath Description

Weg von Wien, Franzosengraben 15 nach Dänenstraße N Hugo- Bezirksamt Wolf- Park Donaupark Döbling (XIX.) Lorenz- Ignaz- Semmelweis- BUS Dänenstraße Böhler- UKH Feuerwache Kaisermühlen Frauenklinik Fin.- BFI Fundamt BUS Türkenschanzpark Verkehrsamt Bezirksamt amt Brigittenau Türkenschanzplatz Währinger Lagerwiese Park Rettungswache (XX.) Gersthof BUS Finanzamt Brigittenau Pensionsversicherung Brigittenau der Angestellten Orthopädisches Rudolf- BUS Donauinsel Kh. Gersthof Czartoryskigasse WIFI Bednar- Währing Augarten Schubertpark Park Dr.- Josef- 10A Resch- Platz Evangelisches AlsergrundLichtensteinpark BUS Richthausenstraße Krankenhaus A.- Carlson- Wettsteinpark Anl. BUS Hernalser Hauptstr./Wattgasse Bezirksamt Max-Winter-Park Allgemeines Krankenhaus Verk.- Verm.- Venediger Au Hauptfeuerwache BUS Albrechtskreithgasse der Stadt Wien (AKH) Amt Amt Leopoldstadt W.- Leopoldstadt Hernals Bezirksamt Kössner- Leopoldstadt Volksprater Park BUS Wilhelminenstraße/Wattgasse (II.) Polizeidirektion Krankenhaus d. Barmherz. Brüder Confraternität-Privatklinik Josefstadt Rudolfsplatz DDSG Zirkuswiese BUS Ottakringer Str./Wattgasse Pass-Platz Ottakring Schönbornpark Rechnungshof Konstantinhügel BUS Schuhmeierplatz Herrengasse Josefstadt Arenawiese BUS Finanzamt Rathauspark U Stephansplatz Hasnerstraße Volksgarten WienU Finanzamt Jos.-Strauss-Park Volkstheater Heldenplatz U A BUS Possingergasse/Gablenzgasse U B.M.f. Finanzen U Arbeitsamt BezirksamtNeubau Burggarten Landstraße- Rochusgasse BUS Auf der Schmelz Mariahilf Wien Mitte / Neubau BezirksamtLandstraßeU -

Hilde Spiel (1911-1990)

Österreichische Literatur im Exil - 2002 © Universität Salzburg Wilhelm Kuehs: Hilde Spiel (1911-1990) Biographische Daten und Kontexte Hilde Spiel (1911-1990) war eine der vielseitigsten Schriftstellerinnen und Essayistinnen des 20. Jahrhunderts, die "Grand Dame der Österreichischen Literatur" (Neue Zürcher Zeitung), deren Werk und Wirken sich auf nahezu alle Genres erstreckte. Ihre intellektuelle und existentielle Biographie steht in enger Korrespondenz zu den großen, dramatischen Ereignissen und Brüchen des 20. Jahrhunderts. Der Glanz des alten Österreich schimmert in vielen Texten durch, vor allem in jenen, die sich mit dem Thema der Assimilation und Integration zugewanderter jüdischer Familien (Arnstein, Eskeles u. a.) in Wien auseinandersetzen und Fragen der Koexistenz und des Antisemitismus nachgehen. Zugleich vermittelt Hilde Spiels Werk die Trauer über den Niedergang bzw. die Exilierung einer Kultur, die in den 20er und frühen 30er Jahren die Autorin tief mitgeprägt hat: die Wiener Moderne in all ihren Facetten von der Literatur über die Musik hin zur Philosophie (Wiener Kreis) sowie die Errungenschaften des "Roten Wien". Schon in ihrem ersten Roman "Kati auf der Brücke" (1931) zeichnete Spiel das individuelle Lebensgefühl der Figuren als mit den großen Fragen der Zeit verknüpft. Sie legt damit einen Text vor, in dem unaufdringlich Möglichkeits- und Handlungsräume ausgelotet, beschritten und verworfen werden. 1936, im selben Jahr wie Stefan Zweig, entschloss sich die inzwischen politisch mit der Linken sympathisierende Autorin gemeinsam mit ihrem späteren Mann Peter de Mendelssohn zur Emigration nach London. Dort fasste sie Fuß als Korrespondentin für Wiener und Prager Zeitungen, arbeitete für die BBC und bald auch für Zeitungen wie den "Daily Express" und "New Statesman" und trat bereits 1937 dem englischen P. -

Exile and Holocaust Literature in German and Austrian Post-War Culture

Religions 2012, 3, 424–440; doi:10.3390/rel3020424 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article Haunted Encounters: Exile and Holocaust Literature in German and Austrian Post-war Culture Birgit Lang School of Languages and Linguistics, The University of Melbourne, Parkville 3010 VIC, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] Received: 2 May 2012; in revised form: 11 May 2012 / Accepted: 12 May 2012 / Published: 14 May 2012 Abstract: In an essay titled ‗The Exiled Tongue‘ (2002), Nobel Prize winner Imre Kertész develops a genealogy of Holocaust and émigré writing, in which the German language plays an important, albeit contradictory, role. While the German language signified intellectual independence and freedom of self-definition (against one‘s roots) for Kertész before the Holocaust, he notes (based on his engagement with fellow writer Jean Améry) that writing in German created severe difficulties in the post-war era. Using the examples of Hilde Spiel and Friedrich Torberg, this article explores this notion and asks how the loss of language experienced by Holocaust survivors impacted on these two Austrian-Jewish writers. The article argues that, while the works of Spiel and Torberg are haunted by the Shoah, the two writers do not write in the post-Auschwitz language that Kertész delineates in his essays, but are instead shaped by the exile experience of both writers. At the same time though, Kertész‘ concept seems to be haunted by exile, as his reception of Jean Améry‘s works, which form the basis of his linguistic genealogies, shows an inability to integrate the experience of exile. -

Rachel Seelig. Strangers in Berlin: Modern Jewish Literature Between East and West, 1913-1933

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 42 Issue 2 Article 28 June 2018 Rachel Seelig. Strangers in Berlin: Modern Jewish Literature Between East and West, 1913-1933. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2016. Adam J. Sacks Brown University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, German Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Sacks, Adam J. (2018) "Rachel Seelig. Strangers in Berlin: Modern Jewish Literature Between East and West, 1913-1933. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2016.," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 42: Iss. 2, Article 28. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.2017 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rachel Seelig. Strangers in Berlin: Modern Jewish Literature Between East and West, 1913-1933. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2016. Abstract Review of Rachel Seelig. Strangers in Berlin: Modern Jewish Literature Between East and West, 1913-1933. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2016. 225 pp. Keywords Berlin; Modernism; Poetry; Jews This book review is available in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl/vol42/ iss2/28 Sacks: Review of Strangers in Berlin Rachel Seelig. Strangers in Berlin: Modern Jewish Literature Between East and West, 1913-1933. -

The House of Wittgenstein: a Family at War Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE HOUSE OF WITTGENSTEIN: A FAMILY AT WAR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alexander Waugh | 333 pages | 20 Apr 2010 | Random House USA Inc | 9780307278722 | English | New York, United States The House of Wittgenstein: A Family at War PDF Book Paul did not expect his debut to sell out. The book is a family history and is a times a bit slow to read. Waugh has an excellent section on the third suicide in the family — that of Kurt, who shot himself, for reasons that remain a mystery, at the end of the war — but of the remaining members of the family, the three sisters, Hermine, Helene and Gretl, he says comparatively little. When Hitler moved into Austria, he was greeted with cheers and salutes. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. The treatment was the female hormone estrogen. Waugh is While it isn't too easy to sympathize much with a fantastically wealthy family that probably made their fortune from some dealings of a patriarch that if they had gone bad would have landed him a jail, Waugh somehow pulls it off. He left the clinic to die at home. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. And it certainly doesn't do the rest of the Wittgenstein's justice. Depression certainly was a hereditary curse: three of the five sons of Karl and Leopoldine Wittgenstein committed suicide—Hans simply disappeared; Kurt, an officer in the Austrian army, shot himself at the end of the Great War; Rudi theatrically drank potassium cyanide at a cafe, after requesting his favorite song. -

Main Addresses

Newsletter for 2017 Summer Course in Vienna TABLE OF CONTENTS MAIN ADDRESSES ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 VIENNA AIRPORT ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 VIENNA CITY MAP ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 TRANSPORT IN VIENNA ............................................................................................................................................... 4 STORES (& Phone SIM-cards) ..................................................................................................................................... 5 MISCELLANEOUS TOURIST INFORMATION.............................................................................................................. 6 TABLET APPS ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 MAIN ADDRESSES University of Vienna, School of Law (Rechtswissenschaftliche Fakultät, Universität Wien), Schottenbastei 10-16, A-1010 Vienna (Town-part: 1. Bezirk-Innere Stadt) [32 minutes’ walk from Austrian Nat’l Defense Academy] www.juridicum.at www.univie.ac.at/techlaw This is the location where classes will be held for the first -

The Jewish Middle Class in Vienna in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

The Jewish Middle Class in Vienna in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Erika Weinzierl Emeritus Professor of History University of Vienna Working Paper 01-1 October 2003 ©2003 by the Center for Austrian Studies (CAS). Permission to reproduce must generally be obtained from CAS. Copying is permitted in accordance with the fair use guidelines of the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976. CAS permits the following additional educational uses without permission or payment of fees: academic libraries may place copies of CAS Working Papers on reserve (in multiple photocopied or electronically retrievable form) for students enrolled in specific courses; teachers may reproduce or have reproduced multiple copies (in photocopied or electronic form) for students in their courses. Those wishing to reproduce CAS Working Papers for any other purpose (general distribution, advertising or promotion, creating new collective works, resale, etc.) must obtain permission from the Center for Austrian Studies, University of Minnesota, 314 Social Sciences Building, 267 19th Avenue S., Minneapolis MN 55455. Tel: 612-624-9811; fax: 612-626-9004; e-mail: [email protected] 1 Introduction: The Rise of the Viennese Jewish Middle Class The rapid burgeoning and advancement of the Jewish middle class in Vienna commenced with the achievement of fully equal civil and legal rights in the Fundamental Laws of December 1867 and the inter-confessional Settlement (Ausgleich) of 1868. It was the victory of liberalism and the constitutional state, a victory which had immediate and phenomenal demographic and social consequences. In 1857, Vienna had a total population of 287,824, of which 6,217 (2.16 per cent) were Jews. -

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples Mittelalter (1150- Wolfram von Eschenbach Epik Parzival (1200/1210) 1450) Gottfried von Straßburg Tristan (ca. 1210) Hartmann von Aue Der arme Heinrich (ca. 1195) Johannes von Tepl Der Ackermann aus Böhmen (ca. 1400) Walther von der Vogelweide Lieder, Oskar von Wolkenstein Minnelyrik, Spruchdichtung Gedichte Renaissance Martin Luther Prosa Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen (1530) (1400-1600) Von der Freyheit eynis Christen Menschen (1521) Historia von D. Johann Fausten (1587) Das Volksbuch vom Eulenspiegel (1515) Der ewige Jude (1602) Sebastian Brant Das Narrenschiff (1494) Barock (1600- H.J.C. von Grimmelshausen Prosa Der abenteuerliche Simplizissimus Teutsch (1669) 1720) Schelmenroman Martin Opitz Lyrik Andreas Gryphius Paul Fleming Sonett Christian v. Hofmannswaldau Paul Gerhard Aufklärung (1720- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Prosa Fabeln 1785) Christian Fürchtegott Gellert Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Drama Nathan der Weise (1779) Bürgerliches Emilia Galotti (1772) Trauerspiel Miss Sara Samson (1755) Lustspiel Minna von Barnhelm oder das Soldatenglück (1767) 2 Sturm und Drang Johann Wolfgang Goethe Prosa Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (1774) (1767-1785) Johann Gottfried Herder Von deutscher Art und Kunst (selections; 1773) Karl Philipp Moritz Anton Reiser (selections; 1785-90) Sophie von Laroche Geschichte des Fräuleins von Sternheim (1771/72) Johann Wolfgang Goethe Drama Götz von Berlichingen (1773) Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz Der Hofmeister oder die Vorteile der Privaterziehung (1774) -

©Copyright 2013 Jan Hengge

©Copyright 2013 Jan Hengge Pure Violence on the Stage of Exception: Representations of Revolutions in Georg Büchner, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Heiner Müller, and Elfriede Jelinek Jan Hengge A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Richard Block, Chair Eric Ames Brigitte Prutti Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Germanics University of Washington Abstract Pure Violence on the Stage of Exception: Representations of Revolutions in Georg Büchner, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Heiner Müller, and Elfriede Jelinek Jan Hengge Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Richard Block Department of Germanics This dissertation examines pertinent issues of today’s terrorism debate in frequently overlooked earlier representations of revolutionary and state violence. At the center of this debate is the state of exception through which the sovereign legitimizes the juridical order by suspending preexisting civil laws. As recent theorists have argued, this has become the paradigm for modern nation states. Walter Benjamin contends, however, that a permanent state of exception has existed since the Baroque and has subjected its victims to an empty eschaton, an end without messianic redemption and devoid of all meaning. As long as the order of the sovereign is based on the dialectical relationship between law- making and law-preserving violence, this state will persevere and the messianic promise will not come to fruition. Thus Benjamin conceives of another category of violence he calls “pure violence,” which lies outside of the juridical order altogether. This type of violence also has the ability to reinstate history insofar as the inevitability of the state of exception has ceased any historical continuity.