Copyright by Elena Anita Watts 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Glengarry News News of Interest

NEWS OF INTEREST NEWS OF INTEREST OF EVERY PAGE THE GLENGARRY NEWS ON EVERY PAGE YOL. XXXII—Xo. 4. ALEXANDRIA, ONTARIO, FRIDAY, PEBRI’ARY 8, 1924- 8 2.00 A YEAR. 1W[ÜÏÏ ïfÀBS Of liB illbanilria 6- IISUIIMI CO. ^Successful Carnival at Sreenfieid ferlorniers Birdliouse Compelilitin lor flfllfi C, I, II., Moalreal, 5; L Alexander Oink I Score Big Success Urban and Bural Pupils Tl)o aimual mooting of tlto Kirk C)iie of the best and most evenly The 30th annual lucetiag of tho T!io nianogcment of Alexand'';- h‘iuk lu keeping v.-ith the reput.n.ti(in al- i At tlu- Alexandria High School, »»n Hill Congregation was held on Tues- contested hockey matches seen in j members of The Glengarry Farmors , believing that variety is tlni spi<-o (,i- ready estabiisiiod by Greenfield for tiio IJMi day of March, there is to bo day, Jan. ' 15 ulto. Report? were Alox-andria for several years Yas play- i Mutual Fire Insurance Co. was hold i life is weekly furnishing pativms ;i'i- novel and attvartive entevtaiuments fin exhibition of robin and phoebo t-ubmittod by ropreseiitativos of lb ed on tho Alexander Rink on Saturday j in tlic Town Hall, here, on ’ruesday j vel, amusi.ng and entortuiuii!:'.»; evon- tile Dramatic Club, under the au-<pir-?s shelters, and of bird houses .suitable <]iff<‘ront organi'/ations. In each the evenikig when tire Canadian Xui-ional afternoon. The attendance fell short j ings and tliat (»f Tliuv.sdny^ 3)sr idtu.. of lî'e l.adios of the Saered Heart .for |nn]»]e martins, 1 reeswmllov s, blue- financial etateincnt w,a« appended 1 Kailway team pdayed against the loeal (if exj>ectations due undoubtedly to lhe j proved more than attractive. -

The Royal Bank of Canada CLASS INSIGNIA

University of Bishop's College J. S. MITCHELL & CO., Limited Lennoxville, Que Wholesale and Retail FOUNDED 1843 ---- ROYAL CHARTER 1883 THE ONLY COLLEGE IN CANADA FOLLOWING THE OXFORD AND CAMBRIDGE PLAN OF THREE LONG ACADEMIC YEARS FOR THE BA. DEGREE HARDWARE Wholesale Distributors in the Province of Quebec for Spalding Sporting Goods Complete courses in Arts and Divinity. Post-Graduate courses in Education leading to the High School diploma. Residential College for men. Women students admitted to lectures and degrees. Valuable scholarships and Exhibitions. The College is situated in one of the most beautiful spots in Eastern Canada. Excellent buildings and equipment. Orders taken for Club Uniforms A ll forms of recreation including golf. Four railway lines converge in Lennoxville. Special Prices for Schools, Colleges and Clubs For information, terms and calendars, apply to: REV. A. H. McGREER, D.D., PRINCIPAL 76 - 80 WELLINGTON STREET NORTH OR TO THE REGISTRAR, Lennoxville, Que. SHERBROOKE i T h e M itr e ESTABLISHED 1893 YEARLY SUBSCRIPTION TWO DOLLARS. SINGLE COPIES FIFTY CENTS. PUBLISHED BY BECK PRESS. REG’D.. LENNOXVILLE. QUE. The Mitre Board declines to be held responsible for opinions expressed by contributors. r T H E MITRE BOARD 1 9 3 0 -3 1 1 j President - - H. L. Hall Hon. President Rev. Prof. F. G. Vial, M.A., B.D., D.C.L. | Hon. Vice-President Prof. W. O. Raymond, Ph.D. Editor-in-Chief C. W. Wiley, B.A. | Secretary Treasurer | Advertising Mgr. ------ E. Osborne Ass’t Advt. Mgr. ------ R. Turley ! ....................... ------ A. Ottiwell i ....................... - - - - - G. H . Tomlinson 1 Circulation A - ----- A. -

A PRISONER in out VILLAGES Public Invited to Legislature J.Egis!Ators Visit Reform School This Morning Members and Find Creditable REBELS' HANDS Will Reply

f ,1 tJ. S. WEATHEE BUBEAU, April 25. Last 24 Hours Kainfall, .01. Tem- SUGAR. 96 Degree Test Centrifugals, perature, Max. 77; Min. 67. Weather, southerly wind with valley showers. 3.95c. Per Ton, $79.00. 88 Analysis Beets, 10s, 6L Per Ton, $84.20. F.ST A RTI STTTCTi JTTL.Y 8 IBs VOL. XIJX, NO. 8334. HONOLULU, HAWAII TERRITORY, MONDAY, APRII, 26, 7T PRICE FIVE CENTS. ,.. I " . ... ...I, - Lfl 1 ddah IlC 'Mill DEBTS ARTHQUAKE IN I HI II U mllu lfl LL WIPED SULTAN NOW PORTUGAL WIPES 1KEJDDHESS OUT BI CROP A PRISONER IN OUT VILLAGES Public Invited to Legislature j.egis!ators Visit Reform School This Morning Members and Find Creditable REBELS' HANDS Will Reply. , Methods. Many Dead, Missing and Injured Among the There will be a joint meeting of the Legislators who visited the Boys' In- American Women in Peril Britain Assures House and Senate this morning, to dustrial School at Waialee yesterday RuinsParliament Votes $100,000 which the general public is invited, are sorry now that they did not visit America of Protection Warships Are when the members will be addressed by the school before the appropriation bill as a Relief Fund. the Honorable Charles W. Fairbanks. items were so thoroughly threshed out, Landing Many Marines. The meeting will commence at eleven as the general concensus of conclusions o'clock and. will be held in the throne reached yesterday after the visit was room, where the House is now sitting. that the school was an admirable one, Arrangements will be made to accom- deserving of the utmost support from . -

Clark Says School Needs More Space

The RCDS DRUMLINE marches in the MLK DAY Parade ... PHOTO BY JAKE O’SHAUGHNESSY Published biweekly by and for the Upper School students of Riverfield Country Day School in Tulsa, OK JANUARYAPRIL 19,3, 2015 2018 THE COMMONS Update on Bixby HS assault in- Clark says vestigation By Maddy Edwards and Staff school needs According to an affidavit released by the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation, a 16- year-old football player at more Space Bixby High School told school officials on Oct. 26 that he had By Jack Bluhm been sexually assaulted by sev- NEWS EDITOR eral teammates a month earlier. The Bixby school board was r. Toby Clark is Head of the Upper and quiet about the incident and Middle Schools here at Riverfield. He didn’t report it to police for a also teaches 9th grade Geometry and week. The board has not re- coaches 5th-6th basketball and Middle leased much information since. and Upper School tennis. Mr. Clark is Not surprisingly, several Mone of the people who gets to decide on big plans for the weeks later this incident is still school, and he gets to finalize pretty much everything for the making headlines. Mr. Clark points out some of the improvements planned for the Upper School. I spoke with him last week about the school’s According to the Tulsa Blue Gym expansion. PHOTO BY MASON MALLOY plans. World, the incident has not been discussed at recent Bixby school Jack: What were some of the challenges in 2017? and provide more space for away fans. -

DJ Music Catalog by Title

Artist Title Artist Title Artist Title Dev Feat. Nef The Pharaoh #1 Kellie Pickler 100 Proof [Radio Edit] Rick Ross Feat. Jay-Z And Dr. Dre 3 Kings Cobra Starship Feat. My Name is Kay #1Nite Andrea Burns 100 Stories [Josh Harris Vocal Club Edit Yo Gotti, Fabolous & DJ Khaled 3 Kings [Clean] Rev Theory #AlphaKing Five For Fighting 100 Years Josh Wilson 3 Minute Song [Album Version] Tank Feat. Chris Brown, Siya And Sa #BDay [Clean] Crystal Waters 100% Pure Love TK N' Cash 3 Times In A Row [Clean] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful Frenship 1000 Nights Elliott Yamin 3 Words Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful [Louie Vega EOL Remix - Clean Rachel Platten 1000 Ships [Single Version] Britney Spears 3 [Groove Police Radio Edit] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And A$AP #Beautiful [Remix - Clean] Prince 1000 X's & O's Queens Of The Stone Age 3's & 7's [LP] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And Jeezy #Beautiful [Remix - Edited] Godsmack 1000hp [Radio Edit] Emblem3 3,000 Miles Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful/#Hermosa [Spanglish Version]d Colton James 101 Proof [Granny With A Gold Tooth Radi Lonely Island Feat. Justin Timberla 3-Way (The Golden Rule) [Edited] Tucker #Country Colton James 101 Proof [The Full 101 Proof] Sho Baraka feat. Courtney Orlando 30 & Up, 1986 [Radio] Nate Harasim #HarmonyPark Wrabel 11 Blocks Vinyl Theatre 30 Seconds Neighbourhood Feat. French Montana #icanteven Dinosaur Pile-Up 11:11 Jay-Z 30 Something [Amended] Eric Nolan #OMW (On My Way) Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [KBCO Edit] Childish Gambino 3005 Chainsmokers #Selfie Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [Radio Edit] Future 31 Days [Xtra Clean] My Chemical Romance #SING It For Japan Michael Franti & Spearhead Feat. -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 2-17-2015 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (2015). The George-Anne. 2633. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/2633 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TUESDAY FEBRUARY 17,2015 GEORGIA SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY WWW.THEGEORGEANNE.COM VOLUME 89, ISSUE 48 6SU.ARE YOU READY FOR A FIGHT NIGHT ? MIGOS BOOKED FOR SPRING OONOERT Hip-hop group Migos was the top-voted artist by students for this year’s spring concert and is scheduled to perform on April 18. Tickets will go on sale this Thursday, SEE PAGE 5 FOR FULL STORY I f I : Michele Norris, Georgia Southern rocks Eagles host Award winning journalist to American College Ga Tech baseball speak at the PAC Theatre Festival game tonight SEE PAGE 4 SEE PAGE 6 SEE PAGE 9 (STheGeorgeAnne For more daily content visit thegeorgeann.com/daily ' 21715 Award-winning author coming to GSU SPORT SHORTS -The Georgia Southern Baseball WfftiHtR Ml BY JOZSEF PAPP publisher Scholastic and a team swept the series ending on The George-Anne staff professor of Young Adult Tuesday Sunday at J.I. Clements Stadium, Literature at The New School with a 9-8 win against the Bethune- David Levithan, an award- in New York. -

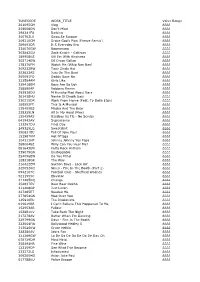

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

Available Now As Ebooks from Intermix and Signet Regency Romance

Discover more Signet Regency Romance treasures! Available now as eBooks from InterMix and Signet Regency Romance Miss Carlyle’s Curricle by Karen Harbaugh An Improper Widow by Kate Moore The Smuggler’s Daughter by Sandra Heath Lady in Green by Barbara Metzger The Reluctant Guardian by Jo Manning To Kiss a Thief by Kate Moore A Perilous Journey by Gail Eastwood The Reluctant Rogue by Elizabeth Powell Miss Clarkson’s Classmate by Sharon Sobel The Bartered Bride by Elizabeth Mansfield The Widower’s Folly by April Kihlstrom A Hint of Scandal by Rhonda Woodward The Counterfeit Husband by Elizabeth Mansfield The Spanish Bride by Amanda McCabe Lady Sparrow by Barbara Metzger A Very Dutiful Daughter by Elizabeth Mansfield Scandal in Venice by Amanda McCabe A Spinster’s Luck by Rhonda Woodward The Ambitious Baronet by April Kihlstrom The Traitor’s Daughter by Elizabeth Powell Lady Larkspur Declines by Sharon Sobel Lady Rogue by Amanda McCabe The Star of India by Amanda McCabe A Lord for Olivia by June Calvin The Golden Feather by Amanda McCabe One Touch of Magic by Amanda McCabe Regency Christmas Wishes Anthology 1 S IGNET R EGENCY R OMANCE An Unlikely Hero Gail Eastwood InterMix Books, New York 2 INTERMIX InterMix Books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group, Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St. -

Junge Final Edit

working working ‘WE ARE GAÚCHOS, WE ARE GAÚCHAS...’ INCITEMENTS TO GENDERED AND REGIONAL SUBJECTIVITY IN THE 2002 395 BRAZILIAN ELECTION CAMPAIGNS December BENJAMIN JUNGE 2013 paper The Kellogg Institute for International Studies University of Notre Dame 130 Hesburgh Center for International Studies Notre Dame, IN 46556-5677 Phone: 574/631-6580 Web: kellogg.nd.edu The Kellogg Institute for International Studies at the University of Notre Dame has built an international reputation by bringing the best of interdisciplinary scholarly inquiry to bear on democratization, human development, and other research themes relevant to contemporary societies around the world. Together, more than 100 faculty and visiting fellows as well as both graduate and undergraduate students make up the Kellogg community of scholars. Founded in 1982, the Institute promotes research, provides students with exceptional educational opportunities, and builds linkages across campus and around the world. The Kellogg Working Paper Series: Shares work-in-progress in a timely way before final publication in scholarly books and journals Includes peer-reviewed papers by visiting and faculty fellows of the Institute Includes a Web database of texts and abstracts in English and Spanish or Portuguese Is indexed chronologically, by region and by research theme, and by author Most full manuscripts downloadable from kellogg.nd.edu Contacts: Elizabeth Rankin, Editorial Manager [email protected] ‘WE ARE GAÚCHOS, WE ARE GAÚCHAS...’ INCITEMENTS TO GENDERED AND REGIONAL SUBJECTIVITY IN THE 2002 BRAZILIAN ELECTION CAMPAIGNS Benjamin Junge Working Paper #395 – December 2013 Benjamin Junge is assistant professor of anthropology at the State University of New York– New Paltz. He is a cultural anthropologist with theoretical specialization in the study of gender, social movements, citizenship, and participatory democracy. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

5204 Songs, 13.5 Days, 35.10 GB

Page 1 of 158 Music 5204 songs, 13.5 days, 35.10 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 I'm All the Way Up 3:12 I'm All the Way Up - Single Dj LaserJet 2 NozeBleedz (feat. Ripp Flamez) 2:39 NozeBleedz (feat. Ripp Flamez)… Ray Jr. 3 All of Me 3:04 The Piano Guys 2 The Piano Guys 4 All of Me 3:03 The Piano Guys 2 (Deluxe Edition) The Piano Guys 5 Three Times a Lady 3:41 Encore - Live at Wembley Arena Lionel Richie 6 The Way You Look Tonight 3:22 Nothing But the Best (Remaster… Frank Sinatra 7 Every Time I Close My Eyes 4:57 A Collection of His Greatest Hits Babyface, Mariah Carey, Kenny… 8 2U (feat. Justin Bieber) 3:15 2U (feat. Justin Bieber) - Single David Guetta 9 A Mother's Day 3:55 Simple Things Jim Brickman 10 Mean To Me 3:49 Bring You Back Brett Eldredge 11 Anywhere 4:04 Room 112 112 12 Don't Drop That Thun Thun 3:22 Don't Drop That Thun Thun - Sin… Finatticz 13 With You 4:12 Exclusive (The Forever Edition) Chris Brown 14 Like Jesus Does 3:19 Chief Eric Church 15 Nice & Slow 3:48 My Way Usher 16 Broccoli (feat. Lil Yachty) 3:45 Broccoli (feat. Lil Yachty) - Single DRAM 17 Grow Old With Me 3:09 Milk and Honey John Lennon 18 When I'm Holding You Tight (Re… 4:10 MSB (Remastered) Michael Stanley Band 19 Hot for Teacher 4:43 1984 Van Halen 20 Death of a Bachelor 3:24 Death Of A Bachelor Panic! At the Disco 21 Family Tradition 4:00 Hank Williams, Jr.'s Greatest Hit… Hank Williams, Jr. -

Promo Only Country Radiodate

URBAN RADIO TITLE 05 01 17 OPEN this on your computer. Place your cursor in the “X” Colum. Use the down arrow to move down the cell and place an “X” infront of the song you want played. Forward the file by attachment to [email protected] or F 713-661-2218 X TRK TITLE ARTIST DATE LENGTH BPM STYLE Mike Will Made-It f./Miley Cyrus, 12 23 Wiz Khalifa & Juicy J 13-Nov 4:08 70 Rhythm/Top 40/Urban 20 100 Game, The f./ Drake 8/1/2015 5:42 110 Hip-Hop 3 679 Fetty Wap f./ Remy Boyz 10/1/2015 3:14 95 Hip-Hop 19 3005 Childish Gambino 14-Jul 3:34 83 Hip-Hop 1 3500 Scott, Travi$ f./ Future & 2 Chainz 9/1/2015 4:50 62 Hip-Hop 3 11-Jul Beyonce 15-Jan 3:31 68 R&B 9 $100 Bill Jay-Z 13-Jul 3:18 66 Rhythm/Urban 2 0 To 100/The Catch Up Drake 14-Sep 4:32 90 Hip-Hop 11 10 2 10 Big Sean 13-Nov 3:22 57 Rhythm/Urban 2 1Hunnid K Camp f./ Fetty Wap 1/1/2016 3:35 87 Hip-Hop 2 1Hunnid K Camp f./ Fetty Wap 1/1/2016 3:35 87 Hip-Hop 16 2 LOVIN U DJ Premier & Miguel 42826 2:58 108 R&B 14 2 Many Doe B f./Rich Homie Quan 14-Jan 4:02 130 Rhythm/Urban 19 2 On Tinashe f./Schoolboy Q 14-May 3:46 101 R&B 13 2 Phones Gates, Kevin 3/1/2016 3:57 61 Hip-Hop 13 2 Phones Gates, Kevin 3/1/2016 3:57 61 Hip-Hop 3 2 Reasons Trey Songz f./T.I.