NFL Draft Experts' Evaluations of Black Quarterbacks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Head Coach Derek Mason

HEAD COACH DEREK MASON Mason speaking to an assembled audience in January after being introduced as the 28th head coach in Vanderbilt football history. Derek Mason, regarded among the nation's top coordinators at Stanford, is the 28th head coach for the Vanderbilt Commodores. Mason, who served as associate head coach and Willie Shaw Director Recent Mason Achievements of Defense for the 2013 Pacific-12 champion Stanford Cardinal, was COACHED IN FOUR CONSECUTIVE BCS BOWLS introduced as the Commodores' coach by Vanderbilt Chancellor Nicholas Since being hired by then-Stanford Head Coach Jim Harbaugh S. Zeppos and Director of Athletics David Williams II in mid-January. prior to 2010 season, Mason has been a key leader in argu- Mason becomes head coach of a Commodore program that has enjoyed ably the greatest era of Cardinal football. In the last four years, consecutive nine-win seasons and postseason Top 25 rankings for the first Stanford has played in four straight BCS bowl games: the 2011 time in team history. The 2013 Vanderbilt squad finished 9-4, capped by a Orange Bowl, 2012 Tostitos Fiesta Bowl, 2013 Rose Bowl and 41-24 victory over Houston in the BBVA Compass Bowl. 2014 Rose Bowl. Alabama is the only other team that can "I am so excited to be at Vanderbilt," Mason said. "This university com- make the same claim. During the four-year period, Stanford bines the best of what's good about college athletics and academics. We owns an overall record of 45-8. expect to be competitive and look forward to competing for an SEC East crown." COACHED BACK-TO-BACK PAC-12 CHAMPION Since arriving on campus, Mason has attracted an outstanding signing class of 22 prospects, assembled a highly qualified staff that includes a TEAMS TO ROSE BOWL APPEARANCES former major college head coach and six coordinators, and effectively rolled Mason's last two years at Stanford with Head Coach David out new offensive and defensive schemes during his initial Spring Practice. -

Vol 39 No 48 November 26

Notice of Forfeiture - Domestic Kansas Register 1 State of Kansas 2AMD, LLC, Leawood, KS 2H Properties, LLC, Winfield, KS Secretary of State 2jake’s Jaylin & Jojo, L.L.C., Kansas City, KS 2JCO, LLC, Wichita, KS Notice of Forfeiture 2JFK, LLC, Wichita, KS 2JK, LLC, Overland Park, KS In accordance with Kansas statutes, the following busi- 2M, LLC, Dodge City, KS ness entities organized under the laws of Kansas and the 2nd Chance Lawn and Landscape, LLC, Wichita, KS foreign business entities authorized to do business in 2nd to None, LLC, Wichita, KS 2nd 2 None, LLC, Wichita, KS Kansas were forfeited during the month of October 2020 2shutterbugs, LLC, Frontenac, KS for failure to timely file an annual report and pay the an- 2U Farms, L.L.C., Oberlin, KS nual report fee. 2u4less, LLC, Frontenac, KS Please Note: The following list represents business en- 20 Angel 15, LLC, Westmoreland, KS tities forfeited in October. Any business entity listed may 2000 S 10th St, LLC, Leawood, KS 2007 Golden Tigers, LLC, Wichita, KS have filed for reinstatement and be considered in good 21/127, L.C., Wichita, KS standing. To check the status of a business entity go to the 21st Street Metal Recycling, LLC, Wichita, KS Kansas Business Center’s Business Entity Search Station at 210 Lecato Ventures, LLC, Mullica Hill, NJ https://www.kansas.gov/bess/flow/main?execution=e2s4 2111 Property, L.L.C., Lawrence, KS 21650 S Main, LLC, Colorado Springs, CO (select Business Entity Database) or contact the Business 217 Media, LLC, Hays, KS Services Division at 785-296-4564. -

Coming Back Stronger

Coming Back STRONGER TYNDALE HOUSE PUBLISHERS, INC., CAROL STREAM, ILLINOIS ComingBackStronger.indd 2 5/10/2010 9:39:52 AM Coming Back STRONGER DREW BREES WITH CHRIS FABRY ComingBackStronger.indd 3 5/10/2010 9:39:55 AM Visit Tyndale’s exciting Web site at www.tyndale.com. Visit Drew Brees’s Web site at www.drewbrees.com. TYNDALE and Tyndale’s quill logo are registered trademarks of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. Coming Back Stronger: Unleashing the Hidden Power of Adversity Copyright © 2010 by Brees Company, Inc. All rights reserved. Front cover photo and author photo of Drew Brees by Stephen Vosloo copyright © 2010 by Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. Back cover photo copyright © 2010 AP Photo/Eric Gay. All rights reserved. Insert photo of Drew holding a rose in his teeth copyright © 2000 AP Photo/Tom Strattman. All rights reserved. Insert photos of Drew and Marty Schottenheimer; and of Drew, LaDainian Tomlinson, and Lorenzo Neal copyright © Mike Nowak. All rights reserved. Insert photo of Drew being helped off the field by Dr. Chao copyright © 2005 AP Photo/Denis Poroy. All rights reserved. Insert photo of boat rescue in St. Bernard Parish copyright © 2005 AP Photo/Eric Gay. All rights reserved. Insert photo of National Guard truck outside the Superdome copyright © 2005 AP Photo/Eric Gay. All rights reserved. Insert photo of aerial view of New Orleans post-Katrina copyright © 2005 AP Photo/David J. Phillip, file. All rights reserved. Insert photos of the Saints home opener in 2006; Drew shaking hands with Sean Payton; Drew leading the pregame chant; Drew dropping back to pass against the Redskins; Drew diving in for a touchdown against Miami; the Saints fan shots; Jon Stinchcomb blocking for Drew; Drew holding the Lombardi Trophy; Drew holding Baylen; and Drew riding in the Super Bowl parade used with express permission of copyright holder New Orleans Louisiana Saints, L.L.C. -

2020 Nfl Draft Round 1 Notes

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 4/23/20 2020 NFL DRAFT ROUND 1 NOTES For reports related to the 2020 NFL Draft, click here. OFFENSE RULES THE FIRST: The 2020 NFL Draft featured 18 offensive players selected in the first round, tied for the fourth-most in the common draft era, trailing only the 1968, 2004 and 2009 NFL Drafts (19). HEISMANS GO FIRST: The Cincinnati Bengals selected Heisman-winning quarterback JOE BURROW with the first-overall pick in the 2020 NFL Draft. Along with the first-overall selections of KYLER MURRAY (Arizona, 2019) and BAKER MAYFIELD (Cleveland, 2018), it marks the first time in the common draft era that a Heisman winner was chosen with the No. 1 pick in three consecutive NFL Drafts. With his selection at No. 1, Burrow joins CAM NEWTON (Carolina, 2011) as the only quarterbacks to win the Heisman Trophy, National Championship and be selected with the first-overall pick in the same calendar year in the common draft era. BUCKEYES AT THE TOP: Washington selected Ohio State defensive end CHASE YOUNG with the second-overall pick while Detroit picked Ohio State defensive back JEFF OKUDAH third-overall in the 2020 NFL Draft. Along with the selections of DENZEL WARD (Cleveland, No. 4 overall in 2018) and NICK BOSA (San Francisco, No. 2 in 2019), Ohio State becomes the first school to have a defensive player selected in the top-five in three consecutive Drafts in the common draft era. Young and Okudah are the first pair of college teammates to be chosen with consecutive top-three selections since the 2000 NFL Draft, when Penn State saw COURTNEY BROWN (Cleveland, No. -

September 2004 Unification News

september 04 10/1/04 1:31 PM Page 1 UnificationUnification NewsNews $2 Volume 23, No. 9 T HE N EWSPAPER OF THE U NIFICATION C OMMUNITY September 2004 PEACE AMBASSADORS TO THE HOLY LAND by Rev. Michael Jenkins is a profound soul who is one of the he pilgrimage most prominent is a historic sheikhs (imams) in journey of the Great Britain. He heart. While shared with us that the violence if anger is not trans- ragesT on both sides formed it is trans- (Buses were bombed in ferred, if hate is not Beer Sheva last week and transformed it will major attacks are going be transferred, if on in the Gaza Strip), our violence is not Peace Ambassadors are transformed it will opening doors in each and be transferred. We every city they go to. From must set the con- Ramallah to Jerusalem dition to transform we go back and forth and the hearts of our the doors are opening. Jewish and Mus- Yesterday we went to Jeri- lims and Christian cho, where Joshua brothers and sis- brought the walls down ters as well as our- not with violence but with selves. the unity of God's people. We must go to a Then later in the day we new level of heart- went to the Wall that is -the revolution of being erected between heart in which we Palestine and Israel. We feel God's love and could feel the power of the heart to com- God that is working to fort God. remove the need for such Today, our Euro- walls. -

Are You Ready for Some Super-Senior Football?

Oldest living players Are you ready for some super-senior football? Starting East team quarterback Ace Parker (Information was current as of May 2013 when article appeared in Sports Collectors Digest magazine) By George Vrechek Can you imagine a tackle football game featuring the oldest living NFL players with some of the guys in their 90s? Well to tell the truth, I can’t really imagine it either. However that doesn’t stop me from fantasizing about the possibility of a super-senior all-star game featuring players who appeared on football cards. After SCD featured my articles earlier this year about the (remote) possibility of a game involving the oldest living baseball players, you knew it wouldn’t be long before you read about the possibility of a super-senior football game. Old-timers have been coming back to baseball parks for years to make cameo appearances. Walter Johnson pitched against Babe Ruth long after both had retired. My earlier articles proposed the possibility of getting the oldest baseball players (ranging in age from 88 to 101) back for one more game. While not very likely, it is at least conceivable. Getting the oldest old-timers back for a game of tackle football, on the other hand, isn’t very likely. We can probably think about a touch game, but the players would properly insist that touch is not the same game. If the game were played as touch football, the plethora of linemen would have to entertain one another, while the players in the skill positions got to run around and get all the attention, sort of like it is now in the NFL, except the linemen are knocking themselves silly. -

University of Nevada, Reno Quarterback Value Forecasting And

University of Nevada, Reno Quarterback Value Forecasting and Fixing the NFL Draft’s Market Failure A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Economics by Trevor M. Wojcik Dr. Mark Nichols/Thesis Advisor December, 2010 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by TREVOR MICHAEL WOJCIK entitled Quarterback Value Forecasting And Fixing The NFL Draft’s Market Failure be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Mark Nichols, Phd, Advisor Sankar Mukhopadhyay, Phd, Committee Member Rahul Bhargava, Phd, Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Associate Dean, Graduate School December, 2010 i Abstract The National Football League (NFL) is a business that is worth nearly $7 billion annually in revenue. That makes it the largest money making sport in the United States. The revenue earned by each franchise is dependent upon the repeated success of the team. A commonly held belief is that for a franchise to be successful you must have an elite Quarterback. This thesis uses NFL data and for the 2000-2008 seasons to determine the role that Quarterback performance plays in team success. With the determination that Quarterbacks are important to NFL team success the question becomes how does a franchise effectively obtain the best player. The NFL player draft is the most commonly used method for teams to find their Quarterback of the future. The problem is that the success rate for drafting Quarterbacks is very low. In this thesis I have determined a more statistical approach to determining whether a drafted Quarterback will be successful. -

Race and College Football in the Southwest, 1947-1976

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE DESEGREGATING THE LINE OF SCRIMMAGE: RACE AND COLLEGE FOOTBALL IN THE SOUTHWEST, 1947-1976 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By CHRISTOPHER R. DAVIS Norman, Oklahoma 2014 DESEGREGATING THE LINE OF SCRIMMAGE: RACE AND COLLEGE FOOTBALL IN THE SOUTHWEST, 1947-1976 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ____________________________ Dr. Stephen H. Norwood, Chair ____________________________ Dr. Robert L. Griswold ____________________________ Dr. Ben Keppel ____________________________ Dr. Paul A. Gilje ____________________________ Dr. Ralph R. Hamerla © Copyright by CHRISTOPHER R. DAVIS 2014 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements In many ways, this dissertation represents the culmination of a lifelong passion for both sports and history. One of my most vivid early childhood memories comes from the fall of 1972 when, as a five year-old, I was reading the sports section of one of the Dallas newspapers at my grandparents’ breakfast table. I am not sure how much I comprehended, but one fact leaped clearly from the page—Nebraska had defeated Army by the seemingly incredible score of 77-7. Wild thoughts raced through my young mind. How could one team score so many points? How could they so thoroughly dominate an opponent? Just how bad was this Army outfit? How many touchdowns did it take to score seventy-seven points? I did not realize it at the time, but that was the day when I first understood concretely the concepts of multiplication and division. Nebraska scored eleven touchdowns I calculated (probably with some help from my grandfather) and my love of football and the sports page only grew from there. -

East Coast Fantasy Football League Draft Results 06-Feb-2006 10:07 AM Eastern

www.rtsports.com East Coast Fantasy Football League Draft Results 06-Feb-2006 10:07 AM Eastern East Coast Fantasy Football League Draft Wed., Sep 7 2005 8:02:00 PM Rounds: 18 Round 1 Round 5 #1 Manny being Manny - LaDainian Tomlinson, RB, SDG #1 Manny being Manny - Lee Suggs, RB, CLE #2 Tyler Durden - Shaun Alexander, RB, SEA #2 Tyler Durden - Larry Johnson, RB, KAN #3 Can U Bird It? - Peyton Manning, QB, IND #3 Can U Bird It? - Hines Ward, WR, PIT #4 Gold Teeth Inc. - Edgerrin James, RB, IND #4 Gold Teeth Inc. - Michael Clayton, WR, TAM #5 Swarming Yeast - Priest Holmes, RB, KAN #5 Swarming Yeast - Marc Bulger, QB, STL #6 Red-Headed Stepchild - LaMont Jordan, RB, OAK #6 Red-Headed Stepchild - Kerry Collins, QB, OAK #7 G In Da Grizzle - Deuce McAllister, RB, NOR #7 G In Da Grizzle - Jason Witten, TE, DAL #8 Confederate Peaches - Willis McGahee, RB, BUF #8 Confederate Peaches - Roy Williams, WR, DET #9 Labrador! - Corey Dillon, RB, NWE #9 Labrador! - Dallas Clark, TE, IND #10 GIT' ER DUN - Ahman Green, RB, GNB #10 GIT' ER DUN - Anquan Boldin, WR, ARI #11 Little Grey Scum Bags - Domanick Davis, RB, HOU #11 Little Grey Scum Bags - Donald Driver, WR, GNB #12 Spivey's World - Daunte Culpepper, QB, MIN #12 Spivey's World - Isaac Bruce, WR, STL Round 2 Round 6 #1 Spivey's World - Tiki Barber, RB, NYG #1 Spivey's World - Alge Crumpler, TE, ATL #2 Little Grey Scum Bags - Julius Jones, RB, DAL #2 Little Grey Scum Bags - Jake Plummer, QB, DEN #3 GIT' ER DUN - Clinton Portis, RB, WAS #3 GIT' ER DUN - Drew Bennett, WR, TEN #4 Labrador! - Kevin Jones, RB, DET #4 Labrador! - Trent Green, QB, KAN #5 Confederate Peaches - Jamal Lewis, RB, BAL #5 Confederate Peaches - Todd Heap, TE, BAL #6 G In Da Grizzle - Randy Moss, WR, OAK #6 G In Da Grizzle - Larry Fitzgerald, WR, ARI #7 Red-Headed Stepchild - Rudi Johnson, RB, CIN #7 Red-Headed Stepchild - Jeremy Shockey, TE, NYG #8 Swarming Yeast - Curtis Martin, RB, NYJ #8 Swarming Yeast - Michael Bennett, RB, MIN #9 Gold Teeth Inc. -

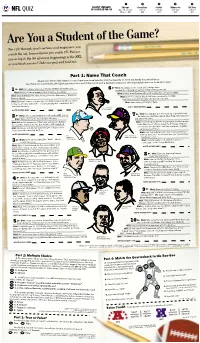

Are You Astudent of Thegame?

C M Y K H6 SPECIALSPT 09-06-06 EZ EE H6 CMYK H6 Wednesday, September 6, 2006 R The Washington Post NFL 2006 1 2 3 3 5 EASIEST STRENGTH Chicago NFL Green Bay Seattle Minnesota N.Y. Jets QUIZ OF SCHEDULE FOR ’06 Opp. ’05: 114-142 115-141 117-139 117-139 119-137 Win pct.: .445 .449 .457 .457 .465 Are You a Student of the Game? You rifle through sports sections and magazines, you search the net, heaven knows you watch TV. But are you as hip to the the offseason happenings of the NFL as you think you are? Take our quiz and find out. Part 1: Name That Coach Nearly one-third of the league’s teams have new head coaches and the majority of them are hardly household faces. See if you can name them. We’ll give you four clues and, if the fourth isn’t a dead giveaway, you should probably move on to another sport. Hint: As a player, was named to the All-Monday Night team. Hint: As running backs coach at San Diego State, Hint: Knows all about winning Super Bowls — as a player. worked directly with future Hall of Famer Marshall Faulk. Hint: Attended Maryland State College (now the University of Maryland Hint: Inducted into Eastern Illinoi s University Hall of Fame in 2000. Eastern Shore). Hint: In first season as Giants offensive coordinator in 2000, Hint: Histeam’sowner—amanwhoisafashion visionary when it comes New York scored 328 points, the most in a decade. to the use of silver and black — regretted firing this coach in his first Hint: Has a strong affinity for Tuna. -

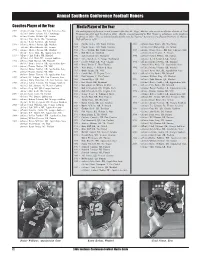

06 FB Records1.Pmd

Annual Southern Conference Football Honors Coaches Player of the Year Media Player of the Year 1989 - (offense) George Searcy, RB, East Tennessee State The media player-of-the-year award is named after Roy M. “Legs” Hawley, who served as athletics director at West (defense) Junior Jackson, LB, Chattanooga Virginia from 1938 until his death in 1954. Hawley was instrumental in West Virginia’s admittance to the Southern 1990 - (offense) Frankie DeBusk, QB, Furman Conferece in 1950. He was inducted posthumously in to the National Association of Collegiate Directors of Athletics (defense) Troy Boeck, DL, Chattanooga Hall of Fame in 1974. (defense) Kevin Kendrick, LB, Furman 1991 - (offense) Michael Payton, QB, Marshall 1948 - Charlie Justice, RB, North Carolina 1988 - (offense) Gene Brown, QB, The Citadel (defense) Allen Edwards, DL, Furman 1949 - Charlie Justice, RB, North Carolina (defense) Jeff Blankenship, LB, Furman 1992 - (offense) Michael Payton, QB, Marshall 1950 - Steve Wadiak, RB, South Carolina 1989 - (offense) George Searcy, RB, East Tennessee State (defense) Avery Hall, DL, Appalachian State 1951 - Bob Ward, G, Maryland (defense) Kelly Fletcher, E, Furman 1993 - (offense) Chris Parker, RB, Marshall 1952 - Jack Scarbath, QB, Maryland 1990 - (offense) Frankie DeBusk, QB, Furman (defense) Alex Mash, DL, Georgia Southern 1953 - Steve Korcheck, C, George Washington (defense) Kevin Kendrick, LB, Furman 1994 - (offense) Todd Donnan, QB, Marshall 1954 - Freddy Wyant, QB, West Virginia 1991 - (offense) Michael Payton, QB, Marshall (defense) -

1 Drafting the Best Future NFL Quarterback Decision Making in A

Drafting the Best Future NFL Quarterback Decision Making in a Complex Environment Final Project Nick Besh Steve Ellis October 18, 2004 Anyone who has followed the NFL draft knows that drafting a Quarterback in the first round is a hit or miss proposition. Successful college prospects, many who are under classmen fail to go on and have the same success as professionals. There are the “cant- miss” prospects who do go one to become Pro Bowl QB’s, but just as many are total busts. It would appear as if the selection is nothing more than a crap-shoot. Drafting is all about priorities and alternatives. Given that, there must be a way to quantify all of the stats and “gut feelings” of players to select a future NFL star. The description of the NFL draft problem would appear to be a perfect candidate for a complex ratings model using the SuperDecisions software. Analyzing the problem further lead us to our stated goal: Optimize a high selection in the NFL draft by drafting a solid contributor to your team, if not a Pro-Bowl caliber player while at the same time avoiding the selection of a player who can set your franchise back years. This is a critical decision that does not leave much room for error. To achieve our goal, thorough research of all the criteria that would need to be considered when drafting a QB would need to be analyzed. This process led us to nine top level criteria: 1 1. Strength of college experience: Just how valuable was the players experience at this level to his future success? • Sub Criteria: College (big/small), college winning percentage, college years started.