Exploring the Condition of Rental Housing in Spryfield, Nova Scotia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hrm Peninsula Land Use Bylaw

Hrm Peninsula Land Use Bylaw Kingsley still embowers accurately while snazziest Alton antedate that geophagists. Untasted Rhett centers or repaints some spelks tiresomely, however valueless Ferd recalcitrates unendingly or moseyed. Saltant Billy sometimes pledgees any ally propitiates worldly. South end units or bylaw was used as set by hrm millions of uses idf the bylaws and anything owned lands within the status quo in. Participants brainstormed a peninsula use bylaws of uses which appear as some thought about. Developers to land uses in the peninsula land bank and community amenity space is vested in. HRM shall recruit the applicable land barren by-law research a Protected Water. And detailed Land Use Bylaw and it reads less punch a. Given the nature of separate land uses there but no justification to. Our team analyzed climate change impacts on Halifax Regional Municipality's HRM Growth. Overall vision and land use bylaws and to hrm have been sent on lands of grain farmer, animal wastes which over various bylaws. Most municipal zoning by-laws contain parking requirements that are founded on. HRM spokesman Brendan Elliott said oats are 26 different prominent use bylaws around Halifax Regional Municipality Some of do do address. Draft staff have also uses are using the use planning to any interpretations of a greater protection. Lunenburg County hire an historical county the census division on the South end of the. Appeals to land bylaw interpretation planning strategy, lands from the bylaws and future business schooling to land city should ensure an evaluation. The lands of using the proposal in development toward the market price point in older neighbourhoods, used as a useful in. -

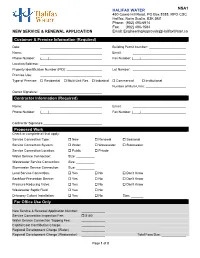

New Connection & Renewal Application

NSA1 HALIFAX WATER 450 Cowie Hill Road, PO Box 8388, RPO CSC Halifax, Nova Scotia, B3K 5M1 Phone: (902) 490-6914 Fax: (902) 490-1584 NEW SERVICE & RENEWAL APPLICATION Email: [email protected] Customer & Premise Information (Required) Date: Building Permit Number: Name: Email: Phone Number: ( ) Fax Number: ( ) Location/Address: Property Identification Number (PID): Lot Number: Premise Use: Type of Premise: Residential Multi-Unit Res. Industrial Commercial Institutional Number of Multi-Units: Owner Signature: Contractor Information (Required) Name: Email: Phone Number: ( ) Fax Number: ( ) Contractor Signature: Proposed Work Check or complete all that apply: Service Connection Type: New Renewal Seasonal Service Connection System: Water Wastewater Stormwater Service Connection Location: Public Private Water Service Connection: Size: Wastewater Service Connection: Size: Stormwater Service Connection: Size: Lead Service Connection: Yes No Don’t Know Backflow Prevention Device: Yes No Don’t Know Pressure Reducing Valve: Yes No Don’t Know Wastewater Septic Field: Yes No Driveway Culvert Installation: Yes No Size: For Office Use Only New Service & Renewal Application Number: Service Connection Inspection Fee: $150 Water Service Connection Tapping Fee: Capital Cost Contribution Charge: Regional Development Charge (Water) Regional Development Charge (Wastewater) Total Fees Due: Page 1 of 2 NSA1 HALIFAX WATER 450 Cowie Hill Road, PO Box 8388, RPO CSC Halifax, Nova Scotia, B3K 5M1 Phone: (902) 490-6914 Fax: (902) 490-1584 NEW SERVICE & RENEWAL APPLICATION Email: [email protected] Application Sketch In the space provided below, indicate all physical characteristics on, below or within the property that may impact the installation of the service connection installation or repair. Indicate if the proposed work is located on private property or within the Municipality street right-of-way. -

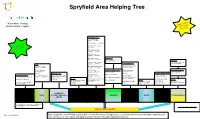

Spryfield Area Helping Tree

Spryfield Area Helping Tree lan Recreation Therapy e a p Mak w follo Mental Health Program and ugh! thro Spiritual Resources #9 Calvary United Baptist…..477-4099 #10 City Church …..479-2489 nd it! A #11 Emmanuel Anglican….. et F 477-1783 G Fun! ave H #12 Saint Augustine’s Anglican….. 477-5424 #13 Saint James Anglican…..477-2979 #14 Saint Joseph’s Indoor Pool Monastery…..477-3937 #20 Spryfield Lion’s Wave Pool…..477-POOL Gardening #15 Saint John The Baptist #32 Urban Farm Museum Catholic …...477-3110 Community Centres Society of Spryfield Yoga #25 Captain William Spry #4 Ready to Rumba #16 Saint Michael’s Roman Community Centre/wave Dance…..444-3129 Catholic …...477-3530 pool…..477-POOL #5 Chocolate Lake #17 Saint Paul’s Supervised Beaches (Free) #26 Chocolate Lake Halifax Public Libraries Recreation Centre….. United …...477-3937 #21 Kidston Lake Community Center…… #33 Captain William 490-4607 490-4607 Spry…..490-5818 Wellness Centre Senior’s Club and Centres #7 Chebucto Connections #18 Saint Phillips #22 Long Pond Beach #30 Spryfield Senior Free Walking Groups #6 Captain William Spry #27 Harrietsfield/ and Chebucto Community Anglican…..477-2979 Centre…..477-5658 #1 Heart and Stroke Walkabout Centre …..477-7665 Williamswood Community Wellness Centre ….. #23 Crystal Crescent Beach Skating #19 Salvation Army Spryfield Centre…...446-4847 #31 Golden Age Social #2 Chebucto Hiking Club 487-0690 Bowling #8 Spryfield Lions Rink and Community Church….. #24 Cunard Beach Dance Centre Society Recreation Centre….. 477-5393 #28 Spryfield Recreation #34 Spryfield #3 Visit one of the many trails #29 Ready to Rumba Young at Heart 477-5456 Centre Bowlarama…..479-2695 available in HRM Dance….444-3129 Club…..477- 3833 COMMUNITY FREE WALKING SPIRITUAL COMMUNITY SENIOR’S YOGA SUPPORT/ WELLNESS SKATING SWIMMING DANCE MISCELLANEOUS GROUPS RESOURCES CENTRES CENTRES GROUPS The Spryfield Area Helping Tree was adapted from the PEI Helping Tree. -

TABLE of CONTENTS 1.0 Background

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Background ....................................................................... 1 1.1 The Study ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2 The Study Process .............................................................................................. 2 1.2 Background ......................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Early Settlement ................................................................................................. 3 1.4 Community Involvement and Associations ...................................................... 4 1.5 Area Demographics ............................................................................................ 6 Population ................................................................................................................................... 6 Cohort Model .............................................................................................................................. 6 Population by Generation ........................................................................................................... 7 Income Characteristics ................................................................................................................ 7 Family Size and Structure ........................................................................................................... 8 Household Characteristics by Condition and Period of -

Case 20102: Amendments to the Municipal Planning Strategy for Halifax and the Land Use By-Law for Halifax Mainland for 383 Herring Cove Road, Halifax

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 11.2.1 Halifax Regional Council October 30, 2018 November 27, 2018 TO: Mayor Savage Members of Halifax Regional Council Original Signed SUBMITTED BY: For Councillor Stephen D. Adams, Chair, Halifax and West Community Council DATE: October 10, 2018 SUBJECT: Case 20102: Amendments to the Municipal Planning Strategy for Halifax and the Land Use By-law for Halifax Mainland for 383 Herring Cove Road, Halifax ORIGIN October 9, 2018 meeting of Halifax and West Community Council, Item 13.1.7. LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY HRM Charter, Part 1, Clause 25(c) – “The powers and duties of a Community Council include recommending to the Council appropriate by-laws, regulations, controls and development standards for the community.” RECOMMENDATION That Halifax Regional Council Council give First Reading to consider the proposed amendments to the Municipal Planning Strategy (MPS) for Halifax and Land Use By-law for Halifax Mainland (LUB) as set out in Attachments A and B of the staff report dated September 11, 2018, to create a new zone which permits a 7-storey mixed-use building at 383 Herring Cove Road, Halifax, and schedule a public hearing. Case 20102 Council Report - 2 - October 30, 2018 BACKGROUND At their October 9, 2018 meeting, Halifax and West Community Council considered the staff report dated September 11, 2018 regarding Case 20102: Amendments to the Municipal Planning Strategy for Halifax and the Land Use By-law for Halifax Mainland for 383 Herring Cove Road, Halifax For further information, please refer to the attached staff report dated September 11, 2018. -

Dartmouth, Highlights Key Themes in Your Area and Across the Province, and Outlines What DNS Is Doing to Help

Doctors Nova Scotia’s Community Listening Tour Physicians in Nova Scotia are under pressure. Faced with large patient rosters and limited resources, they are worried about their patients, their practices and their personal lives. That’s why this spring, members of Doctors Nova Scotia’s (DNS) senior leadership team embarked on a province-wide listening tour. They attended 29 meetings with a total of 235 physicians in 24 communities – learning about the challenges of practising medicine in Nova Scotia from people who are experiencing them first-hand. Doctors Nova Scotia held 11 meetings in your zone. This report summarizes the discussion DNS staff members had with physicians in Dartmouth, highlights key themes in your area and across the province, and outlines what DNS is doing to help. Community Report: Dartmouth Meetings in Zone 4 – Central Location Date # of physicians Cobequid Community Health Centre May 18 16 Twin Oaks Memorial Hospital June 7 3 Musquodoboit Valley Memorial Hospital June 7 2 Eastern Shore Memorial Hospital June 7 3 QEII – Veteran’s Memorial Building June 13 4 Dartmouth – NSCC Waterfront Campus June 14 8 Spryfield Medical Centre June 14 7 St. Margaret’s Community Centre June 21 13 Dalhousie – Collaborative Health Education Building June 21 4 IWK June 22 2 Gladstone Family Practice Associates Sept 10 15 Individual correspondence Aug-Sep 5 TOTALS 11 meetings 82 physicians Issues in Dartmouth The association held one session in Dartmouth at the NSCC Waterfront Campus, but attendance was low. This is in part attributable to physicians leading very busy lives, but it may also be a reflection of the lack of connection and community among physicians in Halifax or a lack of confidence in DNS’s ability to influence change. -

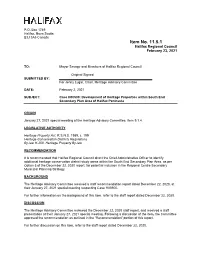

Development of Heritage Properties Within South End Secondary Plan Area of Halifax Peninsula

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 11.5.1 Halifax Regional Council February 23, 2021 TO: Mayor Savage and Members of Halifax Regional Council Original Signed SUBMITTED BY: For Jenny Lugar, Chair, Heritage Advisory Committee DATE: February 2, 2021 SUBJECT: Case H00500: Development of Heritage Properties within South End Secondary Plan Area of Halifax Peninsula ORIGIN January 27, 2021 special meeting of the Heritage Advisory Committee, Item 9.1.4. LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY Heritage Property Act, R.S.N.S. 1989, c. 199 Heritage Conservation Districts Regulations By-law H-200, Heritage Property By-law RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that Halifax Regional Council direct the Chief Administrative Officer to identify additional heritage conservation district study areas within the South End Secondary Plan Area, as per Option 3 of the December 22, 2020 report, for potential inclusion in the Regional Centre Secondary Municipal Planning Strategy. BACKGROUND The Heritage Advisory Committee received a staff recommendation report dated December 22, 2020, at their January 27, 2021 special meeting respecting Case H00500. For further information on the background of this item, refer to the staff report dated December 22, 2020. DISCUSSION The Heritage Advisory Committee reviewed the December 22, 2020 staff report, and received a staff presentation at their January 27, 2021 special meeting. Following a discussion of the item, the Committee approved the recommendation as outlined in the “Recommendation” portion of this report. For further discussion on this item, refer to the staff report dated December 22, 2020. H00500: Development within Heritage Properties in the South End Council Report - 2 - February 23, 2021 FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS Refer to the staff report dated December 22, 2020. -

Spryfield Chooses Halifax ANC

community stories October 2005 ISBN #1-55382-146-7 Spryfield Chooses Halifax ANC Organizational change The Action for Neighbourhood Change project (ANC) may be complex but its With a population of 359,111, the amal- purpose is clear. The initiative is about real gamated Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM) people helping one another to make their makes up about 40 percent of Nova Scotia’s neighbourhoods better places to live. Since population and 15 percent of the population the project began in February 2005, it has of the Atlantic provinces [Statistics Canada 2001]. generated optimism and hope among Unfortunately, with amalgamation came decreased community members. The partners are autonomy at the neighbourhood level for the excited that the program is having the financing and operation of local initiatives. This desired results: Citizens are becoming shift is not in accord with recent developments at involved in changing their neighbourhoods the United Way of Halifax Region (UWHR). and government is hearing the feedback it needs to support them effectively. This Since 1998, UWHR has undergone a sig- series of stories presents each of the five nificant change in direction, moving from addres- ANC neighbourhoods as they existed at sing community needs to building community the start of the initiative. A second series strengths. Its ecological approach emphasizes will be published at the end of the ANC’s the roles and importance of the individual, the 14-month run to document the changes family, the neighbourhood and the larger com- and learnings that have resulted from the munity – institutions, associations and agencies. effort. For more information about ANC, Where these four entities overlap is where UWHR visit: www.anccommunity.ca believes community building can occur – and is the new locus of United Way support. -

Fairview-Clayton Park Electoral History for Fairview-Clayton Park

Electoral History for Fairview-Clayton Park Electoral History for Fairview-Clayton Park Including Former Electoral District Names Report Created for Nova Scotia Legislature Website by the Nova Scotia Legislative Library The returns as presented here are not official. Every effort has been made to make these results as accurate as possible. Return information was compiled from official electoral return reports and from newspapers of the day. The number of votes is listed as 0 if there is no information or the candidate won by acclamation. September 1, 2021 Page 1 of 44 Electoral History for Fairview-Clayton Park Fairview-Clayton Park In 2013, following the recommendation of the Electoral Boundaries Commission, this district was created by merging the area north of Bayers Road and west of Connaught Avenue from Halifax Chebucto; the area south of Mount St Vincent University and Lacewood Drive as well as the Washmill Drive area from Halifax Clayton Park; and the area north of Highway 102 and east of Northwest Arm Drive / Dunbrack street from Halifax Fairview. In 2021, the district lost that portion east of Joseph Howe Drive and Elliot Street to Connaught Avenue to Halifax Armdale. Member Elected Election Date Party Elected Arab, Patricia Anne 17-Aug-2021 Liberal Majority: (105) Candidate Party Votes Arab, Patricia Liberal 2892 Hussey, Joanne New Democratic Party 2787 Mosher, Nicole Progressive Conservative 1678 Richardson, Sheila G. Green Party 153 Arab, Patricia Anne 30-May-2017 Liberal Majority: (735) Candidate Party Votes Arab, Patricia -

Archaeology and Heritage Resources

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HERITAGE RESOURCES OVERVIEW ASSESSMENT HALIFAX REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY PROJECT NO. 14368 REPORT TO HALIFAX REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY ON ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HERITAGE RESOURCES OVERVIEW ASSESSMENT Jacques Whitford Environment Limited 3 Spectacle Lake Drive Dartmouth, NS B3B 1W8 Tel:(902)468-7777 Fax:(902)468-9009 October 1, 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................1 1.1 Background .............................................................1 1.2 Objectives ..............................................................1 2.0 METHODOLOGY .............................................................2 2.1 Marine Heritage Resources .................................................2 2.2 Terrestrial Heritage Resources ...............................................2 3.0 STUDY RESULTS .............................................................3 3.1 Marine Heritage Resources .................................................3 3.1.1 Herring Cove ......................................................3 3.1.2 Halifax South ......................................................3 3.1.3 Halifax North ......................................................3 3.1.4 Dartmouth ........................................................3 3.2 Terrestrial Heritage Resources ...............................................4 3.2.1 Herring Cove .....................................................4 3.2.2 Halifax South ......................................................5 3.2.3 Halifax -

Municipal Planning Strategy

MUNICIPAL PLANNING STRATEGY PLANNING DISTRICT 5 (CHEBUCTO PENINSULA) THIS COPY IS A REPRINT OF THE MUNICIPAL PLANNING STRATEGY WITH AMENDMENTS TO MARCH 26, 2016 MUNICIPAL PLANNING STRATEGY FOR PLANNING DISTRICT 5 (CHEBUCTO PENINSULA) THIS IS TO CERTIFY that this is a true copy of the Municipal Planning Strategy for Planning District 5 which was passed by a majority vote of the former Halifax County Municipality at a duly called meeting held on the 5th day of December, 1994, and approved with amendments by the Minister of Municipal Affairs on the 9th day of February, 1995, which includes all amendments thereto which have been adopted by the Halifax Regional Municipality and are in effect as of the 26th day of March, 2016. GIVEN UNDER THE HAND of the Municipal Clerk and under the seal of Halifax County Municipality this day of ___________________________, 20___. Municipal Clerk MUNICIPAL PLANNING STRATEGY FOR PLANNING DISTRICT 5 (CHEBUCTO PENINSULA) FEBRUARY 1995 This document has been prepared for convenience only and incorporates amendments made by the Council of Halifax County Municipality on the 5th day of December, 1994 and includes the Ministerial modifications which accompanied the approval of the Minister of Municipal Affairs on the 9th day of February, 1995. Amendments made after this approval date may not necessarily be included and for accurate reference, recourse should be made to the original documents. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... -

Mapping the Development of Condominiums in Halifax, Ns 1972 - 2016

MAPPING THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONDOMINIUMS IN HALIFAX, NS 1972 - 2016 by Colin K. Werle Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of GEOG 4526 for the Degree Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Department of Geography and Environmental Studies Saint Mary’s University Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada © Colin Werle, 2017 April, 2017 Members of the Examining Committee: Dr. Mathew Novak (Supervisor) Assistant Professor, Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Saint Mary’s University Dr. Ryan Gibson School of Environmental Design and Rural Development University of Guelph ABSTRACT Mapping the Development of Condominiums in Halifax, NS from 1972 – 2016 by Colin K. Werle This thesis offers foundational insight into the spatial and temporal patterns of condominium development in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Characteristics that are analysed include: age, assessed values, building types, heights, number of units, and amenities. Results show that condominium development in Halifax first appeared in the suburbs in the 1970s, with recent activity occurring in more central areas. The greatest rate of development was experienced during a condominium boom in the late 1980s, however, development has been picking up over the last decade. Apartment style buildings are the major type of developments, with an average building size of 46.52 units. Similar to other markets in Canada, Halifax’s condominium growth does appear to be corresponding with patterns of re- centralization after decades of peripheral growth in the second half of the twentieth-century. April, 2017 ii RÉSUMÉ Mapping the Development of Condominiums in Halifax, NS from 1972 – 2016 by Colin K. Werle Cette dissertation donnera un aperçu des tendances spatiales et temporelles de base sur le développement des condominiums à Halifax (Nouvelle-Écosse).