Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ukraine: Travel Advice

Ukraine: Travel Advice WARSZAWA (WARSAW) BELARUS Advise against all travel Shostka RUSSIA See our travel advice before travelling VOLYNSKA OBLAST Kovel Sarny Chernihiv CHERNIHIVSKA OBLAST RIVNENSKA Kyivske Konotop POLAND Volodymyr- OBLAST Vodoskhovyshche Volynskyi Korosten SUMSKA Sumy Lutsk Nizhyn OBLAST Novovolynsk ZHYTOMYRSKA MISTO Rivne OBLAST KYIV Romny Chervonohrad Novohrad- Pryluky Dubno Volynskyi KYIV Okhtyrka (KIEV) Yahotyn Shepetivka Zhytomyr Lviv Kremenets Fastiv D Kharkiv ( ni D pr ni o Lubny Berdychiv ep Kupiansk er LVIVSKA OBLAST KHMELNYTSKA ) Bila OBLAST Koziatyn KYIVSKA Poltava Drohobych Ternopil Tserkva KHARKIVSKA Khmelnytskyi OBLAST POLTAVSKA Starobilsk OBLAST OBLAST Stryi Cherkasy TERNOPILSKA Vinnytsia Kremenchutske LUHANSKA OBLAST OBLAST Vodoskhovyshche Izium SLOVAKIA Kalush Smila Chortkiv Lysychansk Ivano-Frankivsk UKRAINEKremenchuk Lozova Sloviansk CHERKASKA Luhansk Uzhhorod OBLAST IVANO-FRANKIVSKA Kadiivka Kamianets- Uman Kostiantynivka OBLAST Kolomyia Podilskyi VINNYTSKA Oleksandriia Novomoskovsk Mukachevo OBLAST Pavlohrad ZAKARPATSKA OBLAST Horlivka Chernivtsi Mohyliv-Podilskyi KIROVOHRADSKA Kropyvnytskyi Dnipro Khrustalnyi OBLAST Rakhiv CHERNIVETSKA DNIPROPETROVSKA OBLAST HUNGARY OBLAST Donetsk Pervomaisk DONETSKA OBLAST Kryvyi Rih Zaporizhzhia Liubashivka Yuzhnoukrainsk MOLDOVA Nikopol Voznesensk MYKOLAIVSKA Kakhovske ZAPORIZKA ODESKA Vodoskhovyshche OBLAST OBLAST OBLAST Mariupol Berezivka Mykolaiv ROMANIA Melitopol CHIȘINĂU Nova Kakhovka Berdiansk RUSSIA Kherson KHERSONSKA International Boundary Odesa OBLAST -

Annual Pro 2 Annual Progress Report 2011 Report

ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT 2011 MUNICIPAL GOVERNANCE AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME www.undp.org.ua http://msdp.undp.org.ua UNDP Municipal Governance and Sustainable Development Programme Annual Progress Report 2011 Acknowledgement to Our Partners National Partners Municipality Municipality Municipality Municipality of of Ivano- of Zhytomyr of Rivne Kalynivka Frankivsk Municipality Municipality Municipality Municipality of Novograd- of Galych of Mykolayiv of Saky Volynskiy Municipality Municipality Municipality of Municipality of of Hola of Dzhankoy Kirovske Kagarlyk Prystan’ Municipality of Municipality Municipality of Municipality Voznesensk of Ukrayinka Novovolynsk of Shchelkino Municipality of Municipality Municipality of Municipality Mogyliv- of Lviv Dolyna of Rubizhne Podilskiy Academy of Municipality Municipality of Municipality Municipal of Tulchyn Yevpatoria of Bakhchysaray Management Committee of Settlement Vekhovna Rada on Settlement Settlement of Pervomayske State Construction of Nyzhnegorskiy of Zuya Local Self- Government Ministry of Regional Settlement Development, Settlement Construction, Municipality of of Krasno- of Novoozerne Housing and Vinnytsya gvardiyske Municipal Economy of Ukraine International Partners Acknowledgement to Our Partners The achievements of the project would not have been possible without the assistance and cooperation of the partner municipalities of our Programme, in particular Ivano-Frankivsk, Rivne, Zhytomyr, Galych, Novograd-Volynskiy, Mykolayiv, Kirovske, Hola Prystan’, Kagarlyk, Voznesensk, -

THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION and the SOVIET STATE 1917-1921 STUDIES in RUSSIA and EAST EUROPE Formerly Studies in Russian and East European History

THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION AND THE SOVIET STATE 1917-1921 STUDIES IN RUSSIA AND EAST EUROPE formerly Studies in Russian and East European History Chairman of the Editorial Board: M.A. Branch, Director, School of Slavonic and East European Studies This series includes books on general, political, historical, economic, social and cultural themes relating to Russia and East Europe written or edited by members of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies in the University of London, or by authors wor\ling in a~~oc\at\on '»\\\\ the School. Titles already published are listed below. Further titles are in preparation. Phyllis Auty and Richard Clogg (editors) BRITISH POLICY TOWARDS WARTIME RESISTANCE IN YUGOSLAVIA AND GREECE Elisabeth Barker BRITISH POLICY IN SOUTH·EAST EUROPE IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR Richard Clogg (editor) THE MOVEMENT FOR GREEK INDEPENDENCE, 1770-1821: A COLLECTION OF DOCUMENTS Olga Crisp STUDIES IN THE RUSSIAN ECONOMY BEFORE 1914 D. G. Kirby (editor) FINLAND AND RUSSIA, 1808-1920: DOCUMENTS Martin McCauley THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION AND THE SOVIET STATE, 1917-1921: DOCUMENTS (editor) KHRUSHCHEV AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF SOVIET AGRICULTURE COMMUNIST POWER IN EUROPE 1944-1949 (editor) MARXISM-LENINISM IN THE GERMAN DEMOCRATRIC REPUBLIC: THE SOCIALIST UNITY PARTY (SED) THE GERMAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC SINCE 1945 Evan Mawdsley THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION AND THE BALTIC FLEET The School of Slavonic and East European Studies was founded in 1915 at King's College. Among the first members of staff was Profcs.mr T. G. Masaryk. later President of the Czechoslovak Republic, who delivered the opening lecture in October 1915 on The problems of small nations in the European crisis'. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

F@G-JAN 2021 AHF Facts @ Glance- FINAL Intro Letter 2.9.21.Docx

JANUARY 2021 AHF Facts at a Glance-- Key Highlights: Month-over-month changes—AHF clients & staff — DECEMBER 2020 – JANUARY 2021 AHF Clients: • As of January 2021, and with the February 5, 2021 Global Patient Report, AHF now has 1,501,058 clients in care. • This figure represents a slight census DECREASE (down 4,452 AHF clients or patients worldwide), month-to-month since the January 5, 2020 Global Patient Report. While two (2) new AHF global sites were opened (in VIETNAM and GUATEMALA), twelve sites were closed: 2 in GUATEMALA and 10 in UKRAINE. AHF Staff: • A net increase of 233 AHF employees overall worldwide to 6,728 total AHF employees worldwide, including: o An INCREASE of 16 U.S. staff o A DECREASE of 25 global staff, and o 2,047 other AHF-supported staff in global programs (bucket staff, casuals, etc., down 224) • This report also includes a breakout of the 2,872 clients now enrolled in our various Positive Healthcare (PHC &PHP) Medicare and Medicaid managed care programs in California, Florida and Georgia (page #2 of “Facts”--PHP = Medicare; PHC = Medicaid). US & GLOBAL & PROGRAMS & COUNTRIES: US • NO new domestic U.S. AHF Healthcare Centers, AHF Pharmacies, AHF Wellness or OTC sites opened in December 2020. GLOBAL • AHF's Global program now operates 730 global AHF clinics, ADDING two (2) new treatment sites globally, while CLOSING twelve (12). AHF GLOBAL SITES ADDED IN JANUARY 2021: Week of February 5, 2021 NO new AHF global treatment sites opened and none were closed this week: Week of January 29, 2021 One (1) new global treatment site was ADDED this week and ten (10) were CLOSED: ADDED: • VIETNAM — Tuyen Quang – TQ_Yenson While ten (10) sites were CLOSED, all in UKRAINE, with patients transferred to other treatment sites: • UKRAINE — Kiev – Boyarka (patients transferred to Kiev – Regional Center) • UKRAINE — Kiev – Lunacharskogo (patients transferred to Kyiv – Kiev CC [Kyiv Hospital No. -

Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel Liberman Research Director Brookline, MA Katrina A. Krzysztofiak Laura Raybin Miller Program Manager Pembroke Pines, FL Patricia Hoglund Vincent Obsitnik Administrative Officer McLean, VA 888 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1160 Washington, DC 20006 Ph: ( 202) 254-3824 Fax: ( 202) 254-3934 E-mail: [email protected] May 30, 2005 Message from the Chairman One of the principal missions that United States law assigns the Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is to identify and report on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Central and Eastern Europe associated with the cultural heritage of U.S. citizens, especially endangered sites. The Congress and the President were prompted to establish the Commission because of the special problem faced by Jewish sites in the region: The communities that had once cared for the properties were annihilated during the Holocaust. -

„Lef“ and the Left Front of the Arts

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 142 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Halina Stephan „Lef“ and the Left Front of the Arts Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access S la v istich e B eiträge BEGRÜNDET VON ALOIS SCHMAUS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON JOHANNES HOLTHUSEN • HEINRICH KUNSTMANN PETER REHDER JOSEF SCHRENK REDAKTION PETER REHDER Band 142 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER MÜNCHEN Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 HALINA STEPHAN LEF” AND THE LEFT FRONT OF THE ARTS״ « VERLAG OTTO SAGNER ■ MÜNCHEN 1981 Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München ISBN 3-87690-186-3 Copyright by Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1981 Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner, München Druck: Alexander Grossmann Fäustlestr. 1, D -8000 München 2 Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 To Axel Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................ -

Translating Communism for Children: Fables and Posters of the Revolution

boundary 2 Translating Communism for Children: Fables and Posters of the Revolution Serguei Alex. Oushakine The bourgeoisie knew all too well the importance of children’s litera- ture as a useful tool for strengthening its own dominance. The bourgeoisie did all it could to make sure that our children began as early as possible to absorb the ideas that later would turn them into slaves. We should not forget that the same tools, the same weapons, can be used for the opposite goal. —L. Kormchii, Zabytoe oruzhie: O detskoi knige (Forgotten Weapon: On Children’s Books [1918]) I am grateful to Nergis Ertürk and Özge Serin for the invitation to join this project, and for their insightful comments and suggestions. I also want to thank Marina Balina, David Bellos, Alexei Golubev, Bradley Gorski, Yuri Leving, Maria Litovskaia, Katherine M. H. Reischl, and Kim Lane Scheppele, who read and commented on earlier drafts of this article. My special thanks to Helena Goscilo, without whom this text would look quite different. I am indebted to Thomas F. Keenan, Ilona Kiss, Mikhail Karasik, and Anna Loginova for their help with obtaining visual materials, and I am thankful to the follow- ing institutions for their permission to use images: the Russian Digital Children’s Library (http://arch.rgdb.ru); the Cotsen Children’s Library, Department of Rare Books and Spe- cial Collections, Princeton University Library; and Ne Boltai: A Collection of Twentieth- Century Propaganda (http://www.neboltai.org). All translations of Russian sources are mine, unless otherwise noted. boundary 2 43:3 (2016) DOI 10.1215/01903659- 3572478 © 2016 by Duke University Press Published by Duke University Press boundary 2 160 boundary 2 / August 2016 We will create a fascinating world of “cultural adventures,” inven- tions, struggles, and victories. -

Labor in the Russian Revolution

Labor in the Russian Revolution: Factory Committees and Trade Unions, 1917- 1918 by Gennady Shkliarevsky; Soviet State and Society between Revolutions, 1918-1929 by Lewis H. Siegelbaum; Mary McAuley; The Electrification of Russia, 1880-1926 by Jonathan Coopersmith Review by: Stephen Kotkin The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 67, No. 2 (Jun., 1995), pp. 518-522 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2125137 . Accessed: 10/12/2011 17:28 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Modern History. http://www.jstor.org 518 Book Reviews analyze more deeply the interplay (critical in all revolutionary situations) between street politics and institutional politics and the ways the two created or prevented possibilities for different revolutionaryconclusions. But no criticism should detract from the great achievement of this major work. It will surely become the standardsource on these events for years to come and should be a useful resource for all historians interestedin modern Russian history. JOAN NEUBERGER Universityof Texas at Austin Labor in the Russian Revolution: Factory Committees and Trade Unions, 1917-1918. -

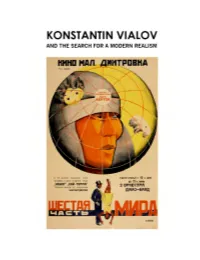

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. -

Deep Time of the Media ELECTRONIC CULTURE: HISTORY, THEORY, and PRACTICE

Deep Time of the Media ELECTRONIC CULTURE: HISTORY, THEORY, AND PRACTICE Ars Electronica: Facing the Future: A Survey of Two Decades edited by Timothy Druckrey net_condition: art and global media edited by Peter Weibel and Timothy Druckrey Dark Fiber: Tracking Critical Internet Culture by Geert Lovink Future Cinema: The Cinematic Imaginary after Film edited by Jeffrey Shaw and Peter Weibel Stelarc: The Monograph edited by Marquard Smith Deep Time of the Media: Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means by Siegfried Zielinski Deep Time of the Media Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means Siegfried Zielinski translated by Gloria Custance The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2006 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Originally published as Archäologie der Medien: Zur Tiefenzeit des technischen Hörens und Sehens, © Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 2002 The publication of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any elec- tronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. I have made every effort to provide proper credits and trace the copyright holders of images and texts included in this work, but if I have inadvertently overlooked any, I would be happy to make the necessary adjustments at the first opportunity.—The author MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] or write to Special Sales Department, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, MA 02142.