The State of the University, 2000-2008: Major Addresses by UNC Chancellor James Moeser

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chapel Hill Methodist Church, a Centennial History, 1853-1953

~bt <lCbaptl 1;111 1Mttbobist €burcb a ~entenntal ,tstOtP, lS53~1953 Qtbe €:bapel i;tll :Metbobigt C!Cbutcb 2l ftentennial ~i6tor!" tS53~1953 By A Committee of the Church Fletcher M. Green, Editor ~bapel ~tll 1954 Contents PREFACE Chapter THE FIRST CHURCH, 1853-1889 By Fletcher M. Green II THE SECOND CHURCH, 1885 -192 0 15 By Mrs. William Whatley Pierson III THE PRESENT CHURCH, 1915-1953 23 By Louis Round Wilson IV WOMEN'S WORK 38 By Mrs.William Whatley Pierson V RELIGIOUS ACTIVITIESOF THE TWENTIETHCENTURY ,------ 52 By Louis Round Wilson and Edgar W. Knight Appendix: LIST OF MINISTERS 65 Compiled by Fletcher M. Green PREFACE Dr. Louis Round Wilson originally suggested the idea of a centennial history of the Chapel Hill Methodist Church in a letter to the pastor, the Reverend Henry G. Ruark, on July 6, 1949. After due consideration the minister appointed a com- mittee to study the matter and to formulate plans for a history. The committee members were Mrs. Hope S. Chamberlain, Fletcher M. Green, Mrs. Guy B. Johnson, Edgar W. Knight, Mrs. Harold G. McCurdy, Mrs. Walter Patten, Mrs. William Whatley Pierson, Mrs. Marvin H. Stacy, and Dr. Louis R. Wilson, chairman. The commilttee adopted a tentative outline and apportioned the work of gathering data among its members. Later Dr. Wilson resigned as chairman and was succeeded by Fletcher M. Green. Others of the group resigned from the committee. Finally, after the data were gathered, Mrs. Pierson, Dr. Green, Dr. Knight, and Dr. Wilson were appointed to write the history. On October 11, 1953, at the centennial cele- bration service Dr. -

Lessons on Political Speech, Academic Freedom, and University Governance from the New North Carolina

LESSONS ON POLITICAL SPEECH, ACADEMIC FREEDOM, AND UNIVERSITY GOVERNANCE FROM THE NEW NORTH CAROLINA * Gene Nichol Things don’t always turn out the way we anticipate. Almost two decades ago, I came to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) after a long stint as dean of the law school in Boulder, Colorado. I was enthusiastic about UNC for two reasons. First, I’m a southerner by blood, culture, and temperament. And, for a lot of us, the state of North Carolina had long been regarded as a leading edge, perhaps the leading edge, of progressivism in the American South. To be sure, Carolina’s progressive habits were often timid and halting, and usually exceedingly modest.1 Still, the Tar Heel State was decidedly not to be confused with Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, or my home country, Texas. Frank Porter Graham, Terry Sanford, Bill Friday, Ella Baker, and Julius Chambers had cast a long and ennobling shadow. Second, I have a thing for the University of North Carolina itself. Quite intentionally, I’ve spent my entire academic career–as student, professor, dean, and president–at public universities. I have nothing against the privates. But it has always seemed to me that the crucial democratizing aspirations of higher education in the United States are played out, almost fully, in our great and often ambitious state institutions. And though they have their challenges, the mission of public higher education is a near-perfect one: to bring the illumination and opportunity offered by the lamp of learning to all. Black and white, male and female, rich and poor, rural and urban, high and low, newly arrived and ancient pedigreed–all can, the theory goes, deploy education’s prospects to make the promises of egalitarian democracy real. -

![Commencement [2009]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5643/commencement-2009-1015643.webp)

Commencement [2009]

I Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/commencement20092009univ COMMENCEMENT 2009 The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill SATURDAY, MAY NINTH and SUNDAY, MAY TENTH TWO THOUSAND NINE Dear Graduates: Congratulations on completing your degree. Dedication and hard work have brought you to this moment. Enjoy it, but also take the opportunity to thank the family and friends who sup- ported you during your journey. I know that they are proud of you, as are all of us at Carolina. I hope that your Carolina education challenged and inspired you and that what you learned here in Chapel Hill prepared you to pursue your dreams. Today you join the ranks of Carolina alumni who have gone out into the world and made a difference. We know you will, too. Today marks a milestone in your life. It is also a milestone for me because this is my first May commencement as chancellor. At my own graduation in 1986, Senior Class President John Kennedy told us that our Carolina experience would stay with us forever. "Chapel Hill is more than just a place," he said. "It is a state of mind." No matter where you go, you will always have that state of mind and the love of all of us here at Carolina. Now go out and change the world. Hark the sound! HOLDEN THORP table of contents 2 Greetings from the Chancellor 4 Alma Mater, "Hark the Sound" 5 The Doctoral Hooding Program 6 The Commencement Program 7 The Chancellor 8 The Doctoral Hooding Speaker 9 Board of Trustees 9 Marshals of the Class of 2009, Officers of the Class of 2009 9 Marshals -

The Restoration of Tolerance

The Restoration of Tolerance Steven D. Smitht In this Article, ProfessorSmith examines the problems that inhere in a value-neutral version of liberalism. He argues that because governing necessarily entails choosing among competing visions of what is good or worthy ofprotection, neutrality is an empty ideal that is incapable of sup- porting a liberal community. Professor Smith therefore rejects the asser- tion that a society must choose between intolerance and neutrality. He argues instead that society's real choice is between tolerance and intoler- ance. He concludes that tolerance, which attempts to give proper respect and scope to the claims of both political community and individualfree- dom, is the only reasonablealternative to intolerance. He then uses recent free exercise of religion andfree speech cases to show how a theory of toler- ance might affect judicial doctrine. Tolerance is a very dull virtue. It is boring. Unlike love, it has always had a bad press. It is negative. It merely means putting up with people, being able to stand things. No one has ever written an ode to tolerance, or raised a statue to her. Yet this is the quality which will be most needed .... -E.M. Forster1 The current crisis in liberal democratic thought has led to a revival of interest in the concept of tolerance.2 Although it has never wholly disappeared from liberal diction, "tolerance," like "patriotism," "higher t Professor of Law, University of Colorado. B.A., Brigham Young University, 1976; J.D. Yale University, 1979. I thank Richard Collins, Frederick Gedicks, Kerry Macintosh, Chris Mueller, Gene Nichol, Pierre Schlag, and the students in my jurisprudence class for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article. -

NPS Form 10-900 (Oct

1 NPS Form 10-900 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. Name of Property Historic name: Old Chapel Hill Cemetery Other name: College Graveyard 2. Location NW corner NC 54 & Country Club Rd, Chapel Hill, NC, 27599 Orange County, Code 135 3. State/Federal Agency Certification Statewide significance 4. National Park Service Certification N/A 5. Classification Ownership of Property: public-local Category of Property: district Number of Resources within Property: 1 noncontributing building, 1 contributing site, 4 contributing and 1 noncontributing structures, 16 contributing and 1 noncontributing objects, 21 contributing and 3 noncontributing total. 6. Function or Use Historic Functions: Funerary/cemetery Current Functions: Funerary/cemetery 7. Description Materials/other: gravemarkers, marble, granite 2 8. Statement of Significance Applicable National Register Criteria A. Property is associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the board patterns of our history. C. Property embodies the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction or represents the work of a master, or possesses high artistic values, or represents a significant and distinguishable entity whose components lack individual distinction. Criteria Considerations D. a cemetery Areas of Significance Social History, Ethnic Heritage: black, Other; Funerary Art Period of Significance 1798-1944 Significant Dates 1798 Narrative Statement of Significance Explained on continuation sheets. 9. Major Bibliographic References Primary location of additional data: State Historic Preservation Office 10. Geographical Data Acreage of Property: 6.98 acres UTM References Zone 17 Easting 676650 Northing 3975600 Verbal Boundary Description and Boundary Justification on continuation sheets 11. -

School of Law

The Magazine of North Carolina Central University School of Law Building on the Legacy Producing Practice-Ready Attorneys Stories from the Practice Front: Civil, Criminal, Bankruptcy, Tax, and Dispute Resolution Our Students at the Supreme Court First Legal Eagle Commencement Reunion North Carolina Central University Volume 15 school of law of Counsel is a magazine for alumni and friends of North Carolina Central University School of Law. Volume 15 / Spring 2013 ofCOUNSEL of Counsel is published by the NCCU Table of Contents School of Law for alumni, friends, and members of the law community. Dean Phyliss Craig-Taylor Former Director of Development Legal Eagle Alumni Awards Delores James Editor Shawnda M. Brown Readings and Features Also In This Issue Copy Editors 15 Brenda Gibson ’95 04 Letter from the Dean Faculty Spotlights Rob Waters 25 05 Practice-Ready Attorneys Alumni News Design and Illustrations 28 Kompleks Creative Group 12 Susie Ruth Powell and “The Loving Story” Donor List Printer 13 Progressive Business Solutions John Britton, Charles Hamilton Houston Chair Photographers 13 Foreclosure Grant Elias Edward Brown, Jr. Tobias Rose Writers and Contributors At School Now Sharon D. Alston Carissa Burroughs 16 Supreme Court Trip Cynthia Fobert 18 Delores James Most Popular US News & World Report 18 PILO Auction 20 Graduation We welcome your comments, suggestions, and ideas for future articles or alumni news. Please send correspondence to: Alumni Events Carissa Burroughs Lorem Ipusm caption Lorem Ipusm caption 22 Dean’s Welcome Reception The NCCU School of Law NCCU School of Law Lorem Ipusm caption Lorem Ipusm caption publishes the of Counsel magazine. -

The Lemon Project: a Journey of Reconciliation Report of the First Eight Years

THE LEMON PROJECT | A Journey of Reconciliation I. SUMMARY REPORT The Lemon Project: A Journey of Reconciliation Report of the First Eight Years SUBMITTED TO Katherine A. Rowe, President Michael R. Halleran, Provost February 2019 THE LEMON PROJECT STEERING COMMITTEE Jody Allen, Stephanie Blackmon, David Brown, Kelley Deetz, Leah Glenn, Chon Glover, ex officio, Artisia Green, Susan A. Kern, Arthur Knight, Terry Meyers, Neil Norman, Sarah Thomas, Alexandra Yeumeni 1 THE LEMON PROJECT | A Journey of Reconciliation I. SUMMARY REPORT Executive Summary In 2009, the William & Mary (W&M) Board of Visitors (BOV) passed a resolution acknowledging the institution’s role as a slaveholder and proponent of Jim Crow and established the Lemon Project: A Journey of Reconciliation. What follows is a report covering the work of the Project’s first eight years. It includes a recap of the programs and events sponsored by the Lemon Project, course development, and community engagement efforts. It also begins to come to grips with the complexities of the history of the African American experience at the College. Research and Scholarship structure and staffing. Section III, the final section, consists largely of the findings of archival research and includes an Over the past eight years, faculty, staff, students, and overview of African Americans at William & Mary. community volunteers have conducted research that has provided insight into the experiences of African Americans at William & Mary. This information has been shared at Conclusion conferences, symposia, during community presentations, in As the Lemon Project wraps up its first eight years, much scholarly articles, and in the classroom. -

Entrepreneurial Spirit

502606 CU Amicus:502606 CU Amicus 12/10/08 11:35 AM Page 1 Amicus UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO LAW SCHOOL VOLUME XXIV, NUMBER 2, FALL 2008 The Entrepreneurial Spirit Inside: • $5 M Gift for Schaden Chair in Experiential Learning • Honor Roll of Donors 502606 CU Amicus:502606 CU Amicus 12/10/08 9:21 AM Page 2 Amicus AMICUS is produced by the University of Colorado Law School in conjunction with University Communications. Electronic copies of AMICUS are available at www.colorado.edu/law/alumdev. S Inquiries regarding content contained herein may be addressed to: la Elisa Dalton La Director of Communications and Alumni Relations S Colorado Law School 401 UCB Ex Boulder, CO 80309 Pa 303-492-3124 [email protected] Writing and editing: Kenna Bruner, Leah Carlson (’09), Elisa Dalton Design and production: Mike Campbell and Amy Miller Photography: Glenn Asakawa, Casey A. Cass, Elisa Dalton Project management: Kimberly Warner The University of Colorado does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national ori- gin, sex, age, disability, creed, religion, sexual orientation, or veteran status in admission and access to, and treatment and employment in, its educational programs and activities. 502606 CU Amicus:502606 CU Amicus 12/8/08 11:02 AM Page 3 2 FROM THE DEAN The Entrepreneurial Spirit 3 ENTREPRENEURS LEADING THE WAY Alumni Ventures Outside the Legal Profession 15 FACULTY EDITORIAL CEO Pay at a Time of Crisis 16 LAW SCHOOL NEWS $5M Gift for Schaden Chair 16 How Does Colorado Law Compare? 19 Academic Partnerships 20 21 LAW SCHOOL EVENTS Keeping Pace and Addressing Issues 21 Serving Diverse Communities 22 25 FACULTY HIGHLIGHTS Teaching Away from Colorado Law 25 Speaking Out 26 Schadens present Books 28 largest gift in Colorado Board Appointments 29 Law history — the Schaden Chair in 31 HONOR ROLL Experiential Learning. -

Racial Justice Movements at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1951-2018

RECLAIMING THE UNIVERSITY OF THE PEOPLE: RACIAL JUSTICE MOVEMENTS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL, 1951-2018 Charlotte Fryar A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of American Studies. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Seth Kotch Rachel Seidman Altha Cravey Timothy Marr Daniel Anderson © 2019 Charlotte Fryar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Charlotte Fryar: Reclaiming the University of the People: Racial Justice Movements at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1951-2018 (Under the direction of Seth Kotch) This dissertation examines how Black students and workers engaged in movements for racial justice at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from 1951 to 2018 challenged the University’s dominant cultural landscape of white supremacy—a landscape in direct conflict with the University’s mission to be a public university in service to all citizens of North Carolina. Beginning with the University’s legal desegregation, this dissertation tells the history of Black students’ and workers’ resistance to institutional anti-Blackness, demonstrating how the University consistently sought to exclude Black identities and diminish any movement that challenged its white supremacy. Activated by the knowledge of the University’s history as a site of enslavement and as an institution which maintained and fortified white supremacy and segregation across North Carolina, Black students and workers protested the ways in which the University reflects and enacts systemic racial inequities within its institutional and campus landscapes. -

Whichard, Willis P

914 PORTRAIT CEREMONY OF JUSTICE WHICHARD OPENING REMARKS and RECOGNITION OF JAMES R. SILKENAT by CHIEF JUSTICE SARAH PARKER The Chief Justice welcomed the guests with the following remarks: Good morning, Ladies and Gentlemen. I am pleased to welcome each of you to your Supreme Court on this very special occasion in which we honor the service on this Court of Associate Justice Willis P. Whichard. The presentation of portraits has a long tradition at the Court, beginning 126 years ago. The first portrait to be presented was that of Chief Justice Thomas Ruffin on March 5, 1888. Today the Court takes great pride in continuing this tradition into the 21st century. For those of you who are not familiar with the Court, the portraits in the courtroom are those of former Chief Justices, and those in the hall here on the third floor are of former Associate Justices. The presentation of Justice Whichard’s portrait today will make a significant contribution to our portrait collection. This addition allows us not only to appropriately remember an important part of our history but also to honor the service of a valued member of our Court family. We are pleased to welcome Justice Whichard and his wife Leona, daughter Jennifer and her husband Steve Ritz, and daughter Ida and her husband David Silkenat. We also are pleased to welcome grand- children Georgia, Evelyn, and Cordia Ritz; Chamberlain, Dawson, and Thessaly Silkenat; and Ida’s in-laws Elizabeth and James Silkenat. Today we honor a man who has distinguished himself not only as a jurist on this Court and the Court of Appeals, but also as a lawyer legislator serving in both Chambers of the General Assembly, as Dean of the Campbell Law School, and as a scholar. -

Carolina Alumni Review November/December 2020 $9

CAROLINA ALUMNI REVIEW NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2020 $9 ND2020_CAR.indd 1 10/28/2020 10:57:57 AM ND2020_CAR.indd 2 10/28/2020 10:59:26 AM ON THE COVER: A majestic maple tree shows off its colors in front of Wilson Hall just off South Road. In the background is the Phi Delta Theta house on Columbia Street. FEATURES | VOL. 109, NO. 6 PHOTO: UNC/CRAIG MARIMPIETRI UNC/JON GARDINER ’98 Science Project 36 Just a planetarium? A Morehead dream that started decades ago is coming to reality: The grand building will showcase all of UNC’s sciences. BY DAVID E. BROWN ’75 Franklin in Hibernation 42 Of course we’re staying home. We’re eating in. We’re mastering self-entertainment. But you sort of have to see The Street in pandemic to believe it. ▲ ▼ ALEX KORMANN ’19 GRANT HALVERSON ’93 PHOTOS BY ALEX KORMANN ’19 AND GRANT HALVERSON ’93 Stateside Study Abroad 52 Zoom has its tiresome limitations. Not as obvious are new possibilities — such as rethinking a writing class as an adventure on the other side of the world. BY ELIZABETH LELAND ’76 NOVEMBER/DECEMBER ’20 1 ND2020_CAR.indd 1 10/28/2020 12:13:14 PM GAA BOARD OF DIRECTORS, 2020–21 OFFICERS Jill Silverstein Gammon ’70, Raleigh .......................Chair J. Rich Leonard ’71, Raleigh ...............Immediate Past Chair Dana E. Simpson ’96, Raleigh ........................Chair-Elect Jan Rowe Capps ’75, Chapel Hill .................First Vice Chair Mary A. Adams Cooper ’12, Nashville, Tenn. Second Vice Chair Dwight M. “Davy” Davidson III ’77, Greensboro . Treasurer Wade M. Smith ’60, Raleigh .............................Counsel Douglas S. -

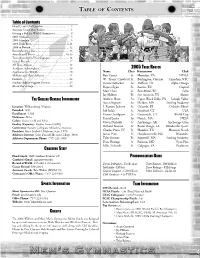

2005 TRIBE ROSTER Application to W&M

TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Head Coach Cliff Gauthier .................................... 2 Assistant Coach Pete Walker ................................... 3 Getting a Feel for W&M Gymnastics ..................... 4 2005 Outlook ........................................................ 5 2005 Schedule ........................................................ 5 2005 Team Bios .................................................6-11 2004 in Review .................................................... 12 Remembering a Hero ........................................... 13 Awards and Honors .........................................14-15 Team Awards/All-Time Captains .......................... 16 School Records ..................................................... 17 All-Time Alumni .................................................. 18 Academic Athmosphere ........................................ 19 2005 TRIBE ROSTER Application to W&M ........................................... 20 Name Class Hometown Club William and Mary Athletics ................................. 21 Ben Carter Sr. Herndon, VA NVGA Facilities ............................................................... 22 W. “Sloan” Crawford Fr. Burlington, Ontario Canadian NTC Student-Athlete Support Services ......................... 23 Devin DeBacker So. Staff ord, TX Alpha Omega About the College ................................................ 24 Rupert Egan Sr. Austin, TX Capital Matt Elson Sr. Brookfi eld, WI Salto Jay Hilbun Fr. San Antonio, TX Alamo THE COLLEGE GENERAL INFORMATION