Legal-Referencer.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Successful Candidates

11 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 1 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath INC 2 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy INC 3 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy INC 4 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla INC 5 Mahabubabad P. Balram INC 6 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao TDP 7 Aruku Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana INC Deo Vyricherla 8 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani INC 9 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha INC 10 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari INC 11 Anakapalli Sabbam Hari INC 12 Kakinada M.M.Pallamraju INC 13 Amalapuram G.V.Harsha Kumar INC 14 Rajahmundry Aruna Kumar Vundavalli INC 15 Narsapuram Bapiraju Kanumuru INC 16 Eluru Kavuri Sambasiva Rao INC 17 Machilipatnam Konakalla Narayana Rao TDP 18 Vijayawada Lagadapati Raja Gopal INC 19 Guntur Rayapati Sambasiva Rao INC 20 Narasaraopet Modugula Venugopala Reddy TDP 21 Bapatla Panabaka Lakshmi INC 22 Ongole Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy INC 23 Nandyal S.P.Y.Reddy INC 24 Kurnool Kotla Jaya Surya Prakash Reddy INC 25 Anantapur Anantha Venkata Rami Reddy INC 26 Hindupur Kristappa Nimmala TDP 27 Kadapa Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy INC 28 Nellore Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy INC 29 Tirupati Chinta Mohan INC 30 Rajampet Annayyagari Sai Prathap INC 31 Chittoor Naramalli Sivaprasad TDP 32 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh TDP 33 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand INC 34 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar INC 35 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud INC 36 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar INC 37 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M TRS 38 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana INC 39 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M INC 40 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi AIMIM 41 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini INC 1 GENERAL ELECTIONS,INDIA 2009 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 42 Mahbubnagar K. -

List of Winning Candidated Final for 16Th

Leading/Winning State PC No PC Name Candidate Leading/Winning Party Andhra Pradesh 1 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh Telugu Desam Andhra Pradesh 2 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 3 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 4 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 5 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 6 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M Telangana Rashtra Samithi Andhra Pradesh 7 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 8 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 9 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi All India Majlis-E-Ittehadul Muslimeen Andhra Pradesh 10 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 11 Mahbubnagar K. Chandrasekhar Rao Telangana Rashtra Samithi Andhra Pradesh 12 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 13 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 14 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 15 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 16 Mahabubabad P. Balram Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 17 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao Telugu Desam Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana Andhra Pradesh 18 Aruku Deo Vyricherla Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 19 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 20 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 21 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari -

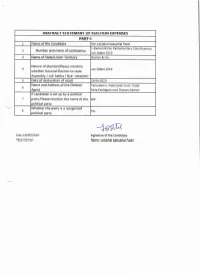

ABSTRACT STATEMENT of ELECTION EXPENSES Name Of

ABSTRACT STATEMENT OF ELECTION EXPENSES PART. L Name of the Candidate Shri Lalubhai babubhai Patel 1-Daman & Diu Parliamentary Constituency 2 Number and name of costituency Lok Sabha 2019 3 Name of State/Union Territory Daman & Diu Nature of election(Please mention 4 Lok Sabha 2019 whether General Election to state Assembly / Lok Sabha / Bye - election) 5 Date of declaration of result 23-05-2019 Name and Address of the Election Tarunaben L Patel,Sabri Kutir, Patel 6 Agent Falia,Kachigo ffi, na ni Da ma n, Daman lf candidate is set up by a political 7 party,Please mention the name of the BJP political party Whether the party is a recognised 8 Yes political party Date -I4/0G12019 Signature of the Candidate P lace-Da ma n Name: Lalubhai babubhai Patel t PART.II: ABSTRCT OF STATEMENT OF ETECTION EXPENDITURE OF CANDIDATE s.NO Particulars Amount Amount Amount Total Election incurred/aut incurre dla incurred/au expenditure horized by uthorized thorized by (31+(41+(sl candidate or by Political Other [in his election Party(in Rs| Rsl agent(in Rsl 1 2 3 4 5 6 Expenses in Public Meeting, Rally,procession etc:-1.a: Expenses in Public meetihB,Rally,procession etc (other than I 8,75,937 35,000 with Star Campaigners of the Political Party)(Enclose as per 88,550 10,00,597 Schedule -1) 1.b :Expenses in Public Meeting, Rally,procession etc with the Star Campaigner (i.e other than those for general L,34,775 party propaganda)(Enclose as per Schedule-2) 1,34,775 Campaign materials other than those used in public meeting ,rally,procession etc mentioned in -

Number and Types of Constituencies

Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2009 (15th LOK SABHA) 3 - NUMBER AND TYPES OF CONSTITUENCIES STATE/UT Type of Constituencies Gen SC ST Total No Of Constituencies Where Election Completed Andhra Pradesh 32 7 3 42 42 Arunachal Pradesh 2 0 0 2 2 Assam 11 1 2 14 14 Bihar 34 6 0 40 40 Goa 2 0 0 2 2 Gujarat 20 2 4 26 26 Haryana 8 2 0 10 10 Himachal Pradesh 3 1 0 4 4 Jammu & Kashmir 6 0 0 6 6 Karnataka 21 5 2 28 28 Kerala 18 2 0 20 20 Madhya Pradesh 19 4 6 29 29 Maharashtra 39 5 4 48 48 Manipur 1 0 1 2 2 Meghalaya 0 0 2 2 2 Mizoram 0 0 1 1 1 Nagaland 0 0 1 1 1 Orissa 13 3 5 21 21 Punjab 9 4 0 13 13 Rajasthan 18 4 3 25 25 Sikkim 1 0 0 1 1 Tamil Nadu 32 7 0 39 39 Tripura 1 0 1 2 2 Uttar Pradesh 63 17 0 80 80 West Bengal 30 10 2 42 42 Chattisgarh 6 1 4 11 11 Jharkhand 8 1 5 14 14 Uttarakhand 4 1 0 5 5 Andaman & Nicobar Islands 1 0 0 1 1 Chandigarh 1 0 0 1 1 Dadra & Nagar Haveli 1 0 0 1 1 Daman & Diu 1 0 0 1 1 NCT OF Delhi 6 1 0 7 7 Lakshadweep 0 0 1 1 1 Puducherry 1 0 0 1 1 Total 412 84 47 543 543 1 Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2009 (15th LOK SABHA) 4 - POLLING STATION INFORMATION Polling Stations General Electors Service Electors Grand Total State/UT PC No. -

Shri Kamal Nath

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATES (Proceedings other than Questions & Answers) ______ Monday, June 1, 2009 / Jyaistha 11, 1931 (Saka) ______ NATIONAL ANTHEM The National Anthem was played OBSERVANCE OF SILENCE MR. SPEAKER PRO TEM (SHRI MANIKRAO HODLYA GAVIT): We are meeting today on a solemn occasion. A new Lok Sabha has been elected under the Constitution charged with great and heavy responsibilities for the welfare of the country and our people. It is fit and proper, as is customary on such an occasion, that we all stand in silence for a short while before we begin our proceedings. The Members then stood in silence for a short while ANNOUNCEMENT BY SPEAKER PRO TEM Welcome to the Members of New Lok Sabha MR. SPEAKER PRO TEM: It gives me great pleasure to welcome all the Members who have been elected to the Fifteenth Lok Sabha. I am sure you will all help the Chair in Maintaining the high traditions of this House and thereby strengthening the roots of parliamentary democracy in our country. I wish you all success in your endeavours. RESIGNATION BY MEMBER MR. SPEAKER PRO TEM: I have to inform the house that the Speaker had received a letter dated the 21 May, 2009 from Shri Akhilesh Yadav, an elected Member from Firozabad and Kannauj constituencies of Uttar Pradesh resigning from the membership of Lok Sabha from the Firozabad constituency of Uttar Pradesh. The Speaker has accepted his resignation with effect from 26th May, 2009. OATH OR AFFIRMATION The following 335 members took the oath or made the affirmation as follows, signed the Roll of members and took their seats in the House. -

Covering Page.Pmd

GENERAL ELECTIONS 2014 Reference Handbook Disclaimer : This Reference Handbook has been prepared by the Press Information Bureau solely for the purpose of providing information to the media persons about past General Elections conducted by the Election Commission of India (ECI). Though all efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy and currency of the contours of this book, the same should not be construed as a statement of law or used for any legal purposes. In case of any ambiguity or doubts, readers are advised to verify /check with the website of ECI or other sources. Statistical Sources & References: The Statistical information/data of past General Elections and various orders of the Election Commission of India (ECI) have been taken from the ECI’s website (www.eci.nic.in) For Feedback: Please send your feedback by email to Shri Rajesh Malhotra, Director ( M&C), Election Commission of India, Press Information Bureau. Email address: [email protected] Contact No : 011-23385993 CONTENTS Section I Schedule for General Elections 2014 Page No. 1. Schedule for General Elections 2014 1 2. State/UT wise Seats in the Lok Sabha 17 3. Parliamentary Constituencies Reserved for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes 19 Section II Demographic Profile of the Electorate 4. A Snapshot of the Indian Electorate for General Elections 2014 23 5. Gender-wise Composition of the Indian Electorate 26 6. Distribution of Indian Electors Aged between 18 and 19 Years across States and Union Territories 29 7. Gender-wise Composition of Indian Electors Aged between 18 and 19 Years 31 8. Comparison of the Indian Electorate from 1951-52 to 2014 34 9. -

S. No. States Name of PC Name of Candidate Phase 1 Uttar Pradesh Varanasi Narendra Damodardas Modi 7 2 Gujarat Gandhinagar Amit

S. No. States Name of PC Name of Candidate Phase 1 Uttar Pradesh Varanasi Narendra Damodardas Modi 7 2 Gujarat Gandhinagar Amit Anil chandra Shah 3 3 Uttar Pradesh Saharanpur Shri Raghav Lakhanpal 1 4 Uttar Pradesh Muzaffarnagar Dr. Sanjeev Kumar Balyan 1 5 Uttar Pradesh Bijnor Kunwar Bharatendra Singh 1 6 Uttar Pradesh Moradabad Shri Kunwar Sarvesh Kumar 3 7 Uttar Pradesh Sambhal Shri Parmeshwar Lal Saini 3 8 Uttar Pradesh Amroha Shri Kanwar Singh Tanwar 2 9 Uttar Pradesh Meerut Shri Rajendra Agrawal 1 10 Uttar Pradesh Baghpat Dr. Satya Pal Singh 1 11 Uttar Pradesh Ghaziabad Dr. Vijay Kumar Singh 1 12 Uttar Pradesh Gautam Buddha Nagar Dr. Mahesh Sharma 1 13 Uttar Pradesh Aligarh Shri Satish Kumar Gautam 2 14 Uttar Pradesh Mathura Smt. Hema Malini 2 15 Uttar Pradesh Agra Shri S P Singh Baghel 2 16 Uttar Pradesh Fatehpur Sikri Shri Raj Kumar Chaher 2 17 Uttar Pradesh Etah Shri Rajveer Singh-MP (Raju Bhaiya) 3 18 Uttar Pradesh Badaun Smt. Sangh Mitra Maurya 3 19 Uttar Pradesh Aonla Shri Dharmendra Kumar 3 20 Uttar Pradesh Bareilly Shri Santosh Kumar Gangwar 3 21 Uttar Pradesh Shahjahanpur (SC) Shri Arun Sagar 4 22 Uttar Pradesh Kheri Shri Ajay Kumar Mishra 4 23 Uttar Pradesh Sitapur Shri Rajesh Verma 5 24 Uttar Pradesh Hardoi (SC) Shri Jai Prakash Rawat 4 25 Uttar Pradesh Misrikh (SC) Shri Ashok Rawat, Ex MP 4 26 Uttar Pradesh Unnao Swami Sakshi Ji Maharaj 4 27 Uttar Pradesh Mohanlalganj (SC) Shri Kaushal Kishore 5 1 28 Uttar Pradesh Lucknow Shri Rajnath Singh 5 29 Uttar Pradesh Amethi Smt. -

Newly Elected Members of 15Th Lok Sabha Took the Oath Or Subscribed the Affirmation

> Title : Newly elected members of 15th Lok Sabha took the oath or subscribed the affirmation. अय महोदय: महासिचव ारा अब सदय के शपथ लेने अथवा पितान करने और हतार करने के पयोजन से सदय के नाम पकु ारे जाएंगे पहले सभा के नेता और तपात् िवप के नेता का नाम पकु ारा जाएगा इसके बाद, शीमती सोिनया गांधी का नाम पकु ारा जाएगा और उसके पात् सभापित तािलका के सदय, काबीना रक के मंितय और और राय मंितय के नाम पकु ारे जाएंगे तपाात्, अय सदय के नाम रायवार/संघ राय ेतवार पकु ारे जाएंग,े जो अडं मान और िनकोबार ीपसमूह, आधं पदेश, अणाचल पदेश से आरभ हग े और इसी कम म िलए जाएंगे पहली बार पकु ारे जाने पर जो सदय शपथ नह ले पाएंग े अथवा पितान नह कर पाएंग,े उनके नाम अतं म दोबारा पकु ारे जाएंगे यिद िकसी सदय के नाम का सही ढंग से उचारण नह हआ हो, तो वह कृ पया मा कर महासिचव MEMBERS SWORN SECRETARY GENERAL : Shri Pranab Mukherjee Shri Pranab Mukherjee (Jangipur) - Oath - English Shri L.K. Advani (Gandhinagar) - Oath - Hindi Shrimati Sonia Gandhi (Rae Bareli) - Affirmation - Hindi Shrimati Sumitra Mahajan (Indore)- Oath - Sanskrit Shri Basudeb Acharia (Bankura) - Affirmation - Bengali Shri Arjun Charan Sethi (Bhadrak) - Affirmation - Oriya Shri Biren Singh Engti - Oath - English (Autonomous District, Assam) Shri Sharad Pawar (Madha) - Affirmation - Hindi Shri P. -

Telephone Directory

TELEPHONE DIRECTORY 2018 U.T. OF DAMAN & DIU AND DADRA & NAGAR HAVELI [ Updated as on 31st August, 2018] Prepared by : Department of Planning & Statistics, Administration of Daman & Diu Secretariat, Daman. CONTENT S.NO. PARTICULAR PAGE NO. 1 STD CODES OF IMPORTANT PLACES 1 2 IMPORTANT TELEPHONE NOS. OF DELHI 2.1 Essential Services at Delhi 3 2.2 VVIPs of Delhi 4 2.3 Liaison Offices at Delhi 5 2.4 NITI Aayog 6 2.5 Other Commissions 8 2.6 Registrar General and Census Commissioner 9 MINISTRIES 2.7 Agriculture 11 2.8 Home Affairs 12 2.9 Health & Family Welfare 15 2.10 Human Resource Development 16 2.11 Personnel, Public Grievances& Pensions 18 2.12 Statistics & Programme Implementation 19 2.13 Social Justice & Empowerment 20 2.14 Tribal Affairs 21 2.15 Other Ministries 22 3 IMPORTANT TELEPHONE NOS. OF DAMAN 3.1 Essential Services at Daman 25 3.2 Secretariat, Daman 26 3.3 Collectorate , Daman 30 3.4 Intercom Nos. of Collectorate 31 3.5 Other Govt. Offices at Daman (1) Accounts Department 32 (2) Agriculture Department 32 (3) Animal Husbandry Department 32 (4) Bal Bhavan 32 (5) Block Development Office 32 (6) Child Development Project Office 32 (7) Civil Registrar Office 32 (8) Official Language 32 (9) Court 32 CONTENT S.NO. PARTICULAR PAGE NO. (10) Sub Jail 32 (11) Daman Municipal Council 33 (12) District Library 33 (13) District Panchayat 33 (14) Pollution Control Committee 33 (15) Environmental Engineer 33 (16) Education Department 34 (17) Electricity Department 35 (18) Fire Station 35 (19) Excise Department 36 (20) Fisheries Department 36 -

Candidate's Name J Lit *

0sc1 FORM 2A (See rule 4) NOMINATION PAPER Election to ihe House of the PeoPle p-- 1n-rn.i-- *{r J lit * STRIKE OFF PART I OR PART II BELOW WHICHEVER IS NOT APPLICABLE PART I (To be used by candidate set up by recognised political party) I nominate as a candidate for election to the House of the People from the..1:.2AMAN. ....k. ..).t.U.M. CN)..Parliamentary constituency. PATEL Candidate' n"m".BlTE!"..-L/1.LU.B.HAl...RABUDlrFaher's/motherslMs name. |KU.TIRz)g'dAaal .RAB.UBliAl..... His postal address tl:l'19:29.k.h,f'A'D.Rl fl uA./.R*s.$t.AAM,NANl bAMANAI62lo His name is entered at s.No..l2.?.......in Part No...10......... ..... of the electoral roll in) Parliamentary for.L. 1 * U*rt..& I t U.l! -Constituencv. il;; is.T..+rl.).EL).E-E.P.E]!/...T.H2!9.5W# ,t is entered at S.No. 1.3.0""i n Part No..f ?......or the electoral roll for ..1.-..D.&nN-'t....A..j.!.1)"(6gf')'.t""tt'uy-"tttstl enmlrised withil) .... .. Parliamentary constitue n I D"t" ?.q.l.q-g-l?o 19 roposer PART II (To be used bY candidate NOT up by recogrrised political panY) We herebY nominate as candi for election to the House of the People from +L^ P iamentary ConstituencY Candidate's name ...Father's/mothcr's/husband's n4me................... .His postal address 1 His name is entered at S.No ......in Part No..... of the electoral roll for 1(Assembly constituency comprised within) Parliamentary constituency We declare that we are electors of the above Parliamen stituency and our names are entered in the electoral roll for that Parliamentary Consti bncy as indicated below and we append our signarures below in token of subscribing to thi omtnatlon:- Particulars of the proposers d their signatures S[.no. -

Opposition Unifier Bhishma Pitamah

10 DECEMBER 1-15, 2019 VOL . 29 ISSUE 11 NEW DELHI PAGES 24 www.utindependent.news US 50c UK p50 Sportspersons Future At Stake Ball In Modi’s Court Jai Maharashtra Opposition Unifier Bhishma Pitamah Darling of Japan PG 2 UNION TERRITORY INDEPENDENT DECEMBER 1-15, 2019 OPINION www.utindependent.news UNION TERRITORY Voiceless Delkar The Lok Sabha passed the bill to merge the INDEPENDENT UTs of Dadra & Nagar Haveli and Daman & Diu as one Union Territory. Now, it will be known as UT of Dadra & Nagar Haveli and Daman & Diu. With passing of the bill, the Justice Delivered UT of Dadra & Nagar Haveli has lost its trib- After the BJP misused the Consti- al identity. After liberated from Portuguese administration, the people ruled the UT for tutional provisions by forming gov- six years and after that, it was merged with ernment at early hours of Novem- Union of India. The Central Government ber 23, all eyes were on the Supreme nominated Sanjibhai Rupjibhai Delkar as first Court to protect the spirit of the Lok Sabha MP, after people elected him. Lat- er on, the people elected him again. Leaders Constitution. The apex court did like late Ramohjibhai, late Ramjibhai Mahala, not show too much hurry but de- Sitaram Gavli, Mohan Delkar and Nattubhai livered the justice that compelled Patel represented the UTs in the Lok Sabha. Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis By winning as an Independent in the last Lok Sabha, Delkar created history to represent and his deputy Ajit Pawar to re- the UT for seventh time in the Lok Sabha. -

Title : a List of Members Elected to 15Th Lok Sabha Was Laid on the Table of the House

> Title : A list of Members elected to 15th Lok Sabha was laid on the Table of the House. अय महोदय: अब म महासिचव से अनुरोध कं गा िक व े भारत के िनवाचन आयोग ारा अय को प तुत वष 2009 के आम िनवाचन म पदं हव लोक सभा के िलए िनवािचत सदय के नाम क सचू ी (िहदी तथा अगं जे ी संकरण) सभापटल पर रख SECRETARY-GENERAL: Sir, I beg to lay on the Table a List (Hindi and English versions), containing the names of Members elected to the Fifteenth Lok Sabha at the General Elections of 2009, submitted to the Speaker by the Election Commission of India. * Laid on the Table and also placed in Library, See No. LT-1/15/09. Party Affiliation Sl. Name of Parliamentary Name of the Elected Member No. Constituency (if any) 1. Andhra Pradesh 1 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh Telugu Desam 2 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand Indian National Congress 3 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar Indian National Congress 4 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud Indian National Congress 5 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar Indian National Congress 6 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M Telangana Rashtra Samithi 7 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana Indian National Congress 8 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M Indian National Congress 9 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi All India Majlis-E-Ittehadul 9 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi Muslimeen 10 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini Indian National Congress 11 Mahbubnagar K. Chandrasekhar Rao Telangana Rashtra Samithi 12 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath Indian National Congress 13 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy Indian National Congress 14 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy Indian National Congress 15 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla Indian National Congress 16 Mahabubabad P.