What Would Animals Say If We Asked the Right Questions?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mini Lesson

BreakingNewsEnglish - The Mini Lesson Cats are just as clever as True / False dogs, says study a) The article says people assume dogs are more intelligent than cats. T / F 28th January, 2017 b) Research into cat intelligence was done at a For whatever university in Japan. T / F reason, people c) Cats ate from 15 bowls as part of a memory assume dogs are test. T / F more intelligent creatures than d) The cats could remember which bowl they ate cats. This notion from. T / F has been called e) Scientists said dogs were better at a whole into question by variety of mental tests. T / F scientists in Japan, who have f) Scientists said cats could not respond to facial said that cats are gestures. T / F as smart as dogs g) A researcher said cats do not recall past at certain memory tests. Cat lovers, of course, have memories like humans. T / F always known this. Researchers at Kyoto University conducted tests on how well 49 cats could recall or h) The researcher said the research was good relate to an event from the past – known as an news for pet owners. T / F episodic memory. The Japanese team got the felines to eat from one of two bowls. Fifteen Synonym Match minutes later, the cats were tested on their ability (The words in bold are from the news article.) to remember which bowl they had eaten from and which remained untouched. The team found the 1. creatures a. assortment cats could recall what they ate and where, 2. -

In the Company of Cats

BRIEF HISTORY In the Company Feline ancestors of today’s domestic of Cats cats still live and thrive in Asia and Africa. How cats have survived, thrived and captivated us for thousands of years. BY SHERRY BAKER f your cat’s bossy analysis shows that most cats had preservation, were both positioned attitude and the stripes and coloring we associate with heads pointed west. entertaining antics with today’s tabby. That suggests to Vigne that the cat have you catering to Archaeological evidence concurs: could well have been a beloved pet. I her needs, you are Stone and clay statues up to 10,000 not alone. Your thoroughly modern years old suggest that cats were kitty is descended from a long line culturally important in the areas GLORY DAYS IN EGYPT of ancestors who likely used those that are now Syria, Turkey and Researchers say that cats have long same skills to cajole, sneak and work Israel. And bones of cats from about been helpers to human farmers in their way into the lives of humans that time period have also been several areas of the Mediterranean for thousands of years. “What sort of philosophers are we, who know absolutely nothing about the origin and destiny of Cats working on farms some 10,000 cats?” the American essayist, naturalist and feline lover Henry years ago, at the dawn of human David Thoreau asked back in the 19th century. Today, the answers agriculture, looked like the tabby of today. are finally at hand: Thanks to new archaeological discoveries and advances in DNA analysis, we’ve come up with some surprising found on the island of Cyprus, where and the Near East. -

Man Critically Injured After Striking Truck Last Tuesday

Tuscola Sheriff asks Chronicle special section: Chemical Bank for residents’ help Spring your home to life presents generous gift Page 4 Pages 6-7 Photo, page 11 Complete coverage of the Cass City community and surrounding areas since 1899 VOLUME 104, NUMBER 52 CASS CITY, MICHIGAN - WEDNESDAY, MARCH 16, 2011 FIFTY CENTS ~ 16 PAGES Man critically injured after striking truck last Tuesday A Cass City man was critically westbound. That vehicle was driven injured last week when the vehicle by Eric Hagen, 50, of Ubly, who was he was driving collided with a semi- not injured. truck just east of town. “Kruse was airlifted to a Saginaw The accident occurred at shortly hospital by FlightCare, then trans- before 10 a.m. Tuesday, according to ferred to Hurley Hospital in Flint, in Tuscola County Undersheriff Glen critical condition,” Skrent said. “He Skrent, who identified the victim as was found not to have been wearing Donald Kruse, 78. a seatbelt.” Skrent reported that Kruse, was MMR ambulance personnel, mem- driving northbound on Schwegler bers of the Elkland Township and A CASS CITY area man Road when he stopped at the stop Elmwood Township-Gagetown fire was listed in critical con- sign at M-81 and then pulled into the departments, and Cass City police dition after the vehicle path of the truck, which was headed assisted at the scene. he was driving struck a semi last week at the Tuscola Co. Sheriff: intersection of M-81 and Schwegler Road. The driver, Donald Kruse, this program will 78, was flown to a Saginaw area hospital, target teen drivers then transferred to Tuscola County Sheriff Lee Teschendorf is again reminding parents of Hurley Hospital in Flint. -

Novel Software Development Process- an Introduction to Cat-Driven

2015 Conference on Cat Information Technology and Applications Novel software development process: An introduction to Cat-driven development (CDD) Chris Liu Ash Wu Pan Cat Technologies | Meow Pan Cat Technologies | Meow [email protected] [email protected] Abstract In recent years, many software development process has been proposed, like Test-driven development and Agile development. They have the same goal: write better code in fewer time. In this paper, we will introduce a novel software development process called Cat-driven development(CDD) to write best code in less time with cats. Keywords: cat, cat-driven development, CDD 1. Introduction pair. Purr Programming has been shown to reduce bugs in code, improve code quality, Software development plays an important introduce team members to new techniques, rule during development time. Communication, and reduce interruptions. design, and programming time will affect whole project progress. To effectively solve problems, 3.2 Cat review bugs in work, we need a smarter development process. We propose a novel software Code review is a common technique in development process: Cat-driven development software development. But it's also very hard (CDD) to solve all problems above mentioned. to apply in practice. We all know how it went when you push tons of changes at once. 2. Background Now we have a better solution: cat review. Cat intelligence is the capacity of the Cats are way smarter than human as we all domesticated cat to learn, solve problems, and agreed. And who have more time and patience adapt to its environment. Research has also than human? Cats. Putting a cat in front of a shown feline intelligence to include the ability to acquire new behavior that applies previously learned knowledge to new situations, communicating needs and desires within a social group, and responding to training cues. -

Road Justice

Rem Jackson Law Offices The Road To JusticeRem Jackson LawStarts Offices Here Accidents | Nursing Home Neglect | Insurance The To September 2018 Starts Here RoaTHE COMPLEXITIESd Justice OF Exclusively Representing WomenschoolAccidents in Divorce, Custody| Nursing bus and Support Home Mattersaccident Neglect and the |Injured Insurance through Noclaims Fault of Their Own. THEFor children COMPLEXITIES injured in school bus accidents OF be responsible for all injuries sustained in what’s inside for which the school district may be at fault, an accident, or at least partially responsible. liability and compensation issues can be trickier School bus owners must also properly inspect, than normal. For example, a public school repair, and maintain their vehicles. page 2 schoolis considered part of the localbus government. accident claims Because a government entity is involved, you Other potential liable parties in a school bus Shrimp in green For children injured in school bus accidents be responsible for all injuries sustained in are required to send the school district—within crash include manufacturers of defective vehicle saucewhat’s inside for which the school district may be at fault, an accident, or at least partially responsible. liabilitya short time and frame—acompensation “notice issues of claim,” can be whichtrickier Schoolparts; the bus local owners or state must government also properly (e.g., inspect, alerts them to your claim and offers them a failing to fix a hazardous road condition or Precautions when than normal. For example, a public school repair, and maintain their vehicles. page 2 chance to respond. If they deny your claim faulty traffic signal); and other drivers who are divorcing an abusive is considered part of the local government. -

John Bradshaw Cat Sense: the Feline Enigma Revealed Allen Lane (London 2013) 336 P

dA.Derecho Animal (Forum of Animal Law Studies) 2019, vol. 10/2 235-238 Book Review John Bradshaw Cat Sense: The Feline Enigma Revealed Allen Lane (London 2013) 336 p. ISBN-13: 978-1846145940 Elizabeth Umlas PhD, Yale University, Independent Researcher MA Candidate in Animal Law & Society Received: April 2019 Accepted: April 2019 Recommended citation. BRADSHAW, J., Cat Sense: The Feline Enigma Revealed (London 2013), rev. UMLAS, E., dA. Derecho Animal (Forum of Animal Law Studies) 10/2 (2019) - DOI https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/da.437 Abstract This is a review of John Bradshaw’s Cat Sense (2013), a comprehensive, accessible and beautifully written book that explores cats and their relationship to human beings through multiple lenses, including history, archaeology, biology, psychology, behavioral science and policy. Keywords: cats; cats and people; domestication; cat behavior; cat physiology; cats and wildlife; future of cats. Resumen Esta es una reseña del Cat Sense (2013) de John Bradshaw, un libro completo, accesible y bellamente escrito que explora el mundo de los gatos y su relación con los seres humanos a través de múltiples lentes, incluida la historia, la arqueología, la biología, la psicología, la ciencia del comportamiento y la política. Palabras clave: gatos; gatos y humanos; domesticación; comportamiento del gato; fisiología del gato; gatos y vida silvestre; el futuro de los gatos. One need not be a “cat person” to enjoy John Bradshaw’s Cat Sense: The Feline Enigma Revealed (Allen Lane, 2013), a book whose style is both sweeping in its scope and careful in its examination of the details. Readers with a general interest in animal behavior and the history of animal-human relationships will be drawn in by the author’s lively style and vivid prose. -

How Smart Is Your Pet? Pet Intelligence Is Hard to Measure

How smart is your pet? Pet Intelligence is hard to measure By Chandra Orr, Creators.com, Calgary Herald March 16, 2011 Different animals have different aptitudes. You think your dog is pretty clever and your cat is a certifiable genius, but how do you know for sure? Your pet's ability to adapt to training, learn new tricks and solve problems reveals a lot, but determining just how smart your furry friend is trickier than you might think. "Our ability to measure a dog's intelligence, even in the most ideal of circumstances, is still limited. I've been training professionally for more than 22 years and still don't feel comfortable in confidently saying that a dog is smart or dumb," says expert trainer and dog behaviourist Jonathan Klein, who heads the award-winning "I Said Sit!" training Exposing your pet to a variety of stimuli creates new and boarding facility. "It's similar to going to a foreign country where neural pathways in his brain, allowing new ways of you don't speak the language. I could interview five people, and if I thinking, so keep that smarty-cat on his toes with plenty of social interaction. Photo courtesy of were asked to rate their order of intelligence, it would be a guess Creator's Syndicate. on my part." All animals, including humans, have inherent aptitudes and hardwired traits to aid in their survival. We excel at reasoning and problem-solving, but gauging a dog's or a cat's intelligence based on the same criteria may not be the "smartest" way to go. -

The Cat's Cradle of Felines and Society

The cat’s cradle of felines and society Cats and American domesticity (1870-1920) Kirsten Weitering Supervisor: Dr. Eduard van de Bilt s1520822 Second reader: Dr. Eric Storm Leiden University August 1, 2019 ResMa History thesis, 30 EC Word count: 25.125 TABLE OF CONTENT Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 Method and sources ............................................................................................. 6 1. A civilization divided: from bird defenders to cat intellectuals ............................ 12 2. The fireside companion of spinsters and ladies ................................................. 30 3. The housecat as gateway to the public sphere ................................................... 52 Conclusion ............................................................................................................ 73 Bibliography .......................................................................................................... 76 Primary sources ................................................................................................. 76 Secondary literature........................................................................................... 85 Images on the front page: “Dandy.” Light Cream Buff. Robert Kent James, The Angora Cat: How to Breed, Train and Keep It; With Additional Chapter on the History, Peculiarities and Diseases of the Animal (Boston 1898) 100-101; Caring for Pets. Frances E. Willard, Occupations -

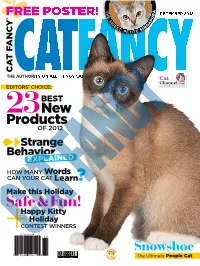

Cat Breeder Directory CAT FANCY, P.O

T CAT FANCY FANCY CAT EXPLAINED BEHAVIOR • STRANGE & FUN HOLIDAY OF 2012 • SAFE NEW PRODUCTS • SINGAPURA BEST SNOWSHOE DECEMBER 2012 H A DECEMBER 2012 FREE POSTER! R E ® U S W P A E G E N T, SI * PETITE CAT FANCY CAT THE AUTHORITY ON ALL THINGS CAT ® EDITORS’ CHOICE: BEST New 23Products OF 2012 ➻ Strange Behavior EXPLAINED HOW MANY Words CAN YOUR CAT Learn? Make this Holiday Safe&Fun! Happy Kitty Holiday + CONTEST WINNERS Snowshoe The Ultimate People Cat CCFcover1212.inddFcover1212.indd 1 99/24/12/24/12 88:33:09:33:09 AAMM C2_C3_C4_CF1212 9/21/12 9:40 AM Page Cov2 Born to climb Born to stalk Born to pounce Did you know the African Wildcat is an original ancestor of your domestic cat? At Purina ONE, we believe that by better understanding the behavior and needs of the African Wildcat, we can understand who our cats were born to be and deepen our relationship with them. Why do cats jump? Pounce? Stalk? Join our journey online to learn more. > www.purinaone.com/borntobe Discover your cat’s true nature. ® ® All trademarks are owned by Société des Produits Nestlé S.A. or used with permission. Printed in U.S.A. 1EdNote1212 9/21/12 9:55 AM Page 1 FROM THE EDITOR VOLUME 55 • NUMBER 12 DECEMBER 2012 Holiday Miracles Editor Susan Logan Managing Editor Annie B. Shirreffs Managing Web Editor Anastasia Thrift HOW DOES A DAYS-OLD KITTEN SURVIVE GETTING SWEPT Art Director Jerome Callens up by a tornado and flung onto the top of a tree? Pre-weaned kittens Group Editor Ernie Slone Web Editorial Director require so much around-the-clock care that it doesn’t seem possible Melissa Kauffman that one, aptly named Toto, could survive that. -

To Download a PDF of Our January, 2018 Edition

H PUBLISHED IN NORTHEAST PORTLAND SINCE 1984 H STAR PUBLISHING INC. STAR JANE DOUGH IS A 'GO' THE HOLLYWOOD Urban farmer Stacey Givens plans community kitchen for Carolyn Westerfield's Jane Dough project in the Cully neighborhood. PAGE 6 H SERVING NORTHEAST AND NORTH METROPOLITANNEWS PORTLAND NEIGHBORHOODS H JANUARY 2018 H VOLUME 35, NUMBER 7 H Star H Child welfare issues are a principal issue for Rep. Tawna Sanchez, the second known Native American MARKING A MILESTONE Hollywood's Mountain elected to the Oregon Legislature. Shop celebrates 80 years in Northeast Portland. PAGE 14 After working with youth and families for 20 years, she earned a masters degree in social TALKINGTO work in 2012. She has won national recognition for her work in education and to combat Tawna domestic and A CHAMPION FOR CHILDREN sexual violence. (Janet Goetze) By Janet Goetze a member of both the Judiciary Committee and the [email protected] Joint Ways and Means Subcommittee on Public Safety. Those assignments reflect her interest in providing more Tawna Sanchez threw back her head and laughed affordable housing, conserving natural resources and, WHAT'S THE COMMOTION? Theresia Munywoki will at the idea that she was “too nice and trying to please she said, “pushing to make our criminal justice system launch multicultural movement studio on 42nd Ave. PAGE 9 everyone” during the 2017 Legislative session, which more humane.” was her first as the representative for District 43. Sanchez began working as a community activist in “They don’t know me,” said Sanchez, responding to a the 1980s when she moved to California to push for weekly newspaper’s comments, collected from lobbyists the rights of women and indigenous people. -

Alexander and Some Other Cats

UNIVERSITE mm i$z&y UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES Date Due APR 0 7 1991 *nmn— SfP j 5 ^ 1770fQQS—00ST751 JUN 2 0 1995 sc York Form — Cooper Graphics Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/alexandersomeothOOeddy ALEXANDER AND SOME OTHER CATS Alexander ALEXANDER AND SOME OTHER CATS Compiled and arranged by SARAH J. EDDY MARSHALL JONES COMPANY BOSTON • MASSACHUSETTS COPYRIGHT 1929 BY MARSHALL JONES INCORPORATED Printed in April, 1929 THE PLIMPTON PRESS • NORWOOD • MASSACHUSETTS MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA { Dedicated TO ALL THOSE WHO LOVE CATS AND TO ALL THOSE WHO DO NOT LOVE THEM BECAUSE THEY DO NOT KNOW THEM CONTENTS Foreword What has been Said about Cats Quotations from Edward E. Whiting, Philip G. Hamerton, Agnes Repplier, Theophile Gautier, William Lyon Phelps, St. George Mivart, Professor Romanes and many others. Grace and beauty of cats — their sensitiveness and intelligence — their capacity for affection — their possession of language. Famous Persons who have Loved Cats. The Intelligence of Cats Incidents to show that cats understand human language; easily become adept at using mechanical appliances, clearly express their needs and desires and often show interest and helpfulness toward other animals. Mother Love of Cats Dr. Gordon Stables on the depth of the maternal instinct in cats. Stories to illustrate the devotion of cats to their young. Cats as foster mothers. Kittens The Poets on Kittens. Miss Repplier's description of a kitten. Kittens and little children. Affection for Persons Stories that show how much affection cats have for their owners. Individual Cats Alexander, Togo, Toby and Timothy, Tabs, Tootsie, Tom, Agrippina, Friday, Tripp, Mephisto, Thomas Erastus, John Steven McCroarty's " Yellow Cat," Fluffy, Bialka. -

Out with the Old Farewell Artcenter Hello Oolite Arts

April 2019 www.BiscayneTimes.com Volume 17 Issue 2 © Out With the Old Farewell ArtCenter Hello Oolite Arts CALL 305-756-6200 FOR INFORMATION ABOUT THIS ADVERTISING SPACE 2 Biscayne Times • www.BiscayneTimes.com April 2019 DISCOVER | JWTURNBERRY.COM CHAMPIONSHIP GOLF COURSES | COUNTRY CLUB | MEETING & CONVENTION CENTER SOFF’S | BOURBON STEAK BY MICHAEL MINA | CORSAIR KITCHEN & BAR TIDAL COVE WATER PARK | ÂME SPA & WELLNESS COLLECTIVE April 2019 Biscayne Times • www.BiscayneTimes.com 3 Where Buyers 2019 New 5,300 SF Waterfront Home 160 ft of New Seawall ! and Sellers ` intersect every day 13255 Keystone Terrace - $1.650M Rare opportunity to find a 160 ft waterfront home with 2019 New Waterfront Pool Home - $2.49M new seawall just steps to the Bay! For sale at lot New 5,300 SF Contemporary Home with Ocean Access, no value. 160' ft on water with no bridges to Bay… Remodel bridges to Bay. 4BR, 5BA + den/office or 5th BR, 665sf this 5BR 4,589 sf home with your personal touches or covered patio downstairs. 2 car gar. Dock up to 75' ft boat. build your waterfront dream home on 13,000 sf lot. For Rent-Keystone Point Waterfront Tropical Oasis on 20,000 SF of Land! Brand New 2019 Waterfront Home ! 2045 Keystone Blvd - $2.39M New modern style home rests on 75 ft of waterfront, no bridges to Bay & quick ocean access. Appx 5,000 sf, 5br 5ba, pool, 2 car garage. New seawall and new dock. 13800 S Biscayne River Dr - $415,000 Wow! 20,000 sf of land is rare to find! Enjoy this Completely Remodeled - $5,500 13100 Coronado Terr.