William Hogarth: Painter, Engraver, and Philosopher. Essays on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“What Is the Use of a Book Without Pictures?” an Exploration of The

Children’s Literature in Education DOI 10.1007/s10583-016-9279-1 ORIGINAL PAPER ‘‘What is the Use of a Book Without Pictures?’’ An Exploration of the Impact of Illustrations on Reading Experience in A Monster Calls Jen Aggleton1 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This article examines the effect of Jim Kay’s illustrations on the experience of reading A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness. The author compares the responses of six Key Stage Three children (11–14 years old), three of whom were given an illustrated version of the text, and three a non-illustrated version. The children with an illustrated copy engaged with the text more deeply and critically than the others. They were also more likely to relate the story to their own lives. The illustrations were found to work alongside the participants’ own visualisations rather than replacing them, and opened up further possible interpretations rather than limiting them. The illustrations did not appear to have influenced the partici- pants’ overall enjoyment of the book, nor did they significantly alter the readers’ views on key themes and ideas of the text. Keywords Illustrations Á A Monster Calls Á Reading Experience Á Literacy Education In 2011, Walker Books published A Monster Calls, a young adult novel written by Patrick Ness, based on an original idea by Siobhan Dowd, who tragically died from cancer before being able to write the book herself. Dowd’s publishers asked Ness to fulfil the original concept, and commissioned Jim Kay to illustrate it. -

Drinkerdrinker

FREE DRINKERDRINKER Volume 41 No. 3 June/July 2019 The Anglers, Teddington – see page 38 WETHERSPOON OUR PARTNERSHIP WITH CAMRA All CAMRA members receive £20 worth of 50p vouchers towards the price of one pint of real ale or real cider; visit the camra website for further details: camra.org.uk Check out our international craft brewers’ showcase ales, featuring some of the best brewers from around the world, available in pubs each month. Wetherspoon also supports local brewers, over 450 of which are set up to deliver to their local pubs. We run regular guest ale lists and have over 200 beers available for pubs to order throughout the year; ask at the bar for your favourite. CAMRA ALSO FEATURES 243 WETHERSPOON PUBS IN ITS GOOD BEER GUIDE Editorial London Drinker is published on behalf of the how CAMRA’s national and local Greater London branches of CAMRA, the campaigning can work well together. Of Campaign for Real Ale, and is edited by Tony course we must continue to campaign Hedger. It is printed by Cliffe Enterprise, Eastbourne, BN22 8TR. for pubs but that doesn’t mean that we DRINKERDRINKER can’t have fun while we do it. If at the CAMRA is a not-for-profit company limited by guarantee and registered in England; same time we can raise CAMRA’s profile company no. 1270286. Registered office: as a positive, forward-thinking and fun 230 Hatfield Road, St. Albans, organisation to join, then so much the Hertfordshire AL1 4LW. better. Material for publication, Welcome to a including press The campaign will be officially releases, should preferably be sent by ‘Summer of Pub’ e-mail to [email protected]. -

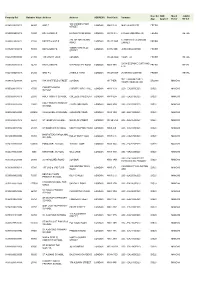

Venue Id Venue Name Address 1 City Postcode Venue Type

Venue_id Venue_name Address_1 City Postcode Venue_type 2012292 Plough 1 Lewis Street Aberaman CF44 6PY Retail - Pub 2011877 Conway Inn 52 Cardiff Street Aberdare CF44 7DG Retail - Pub 2006783 McDonald's - 902 Aberdare Gadlys Link Road ABERDARE CF44 7NT Retail - Fast Food 2009437 Rhoswenallt Inn Werfa Aberdare CF44 0YP Retail - Pub 2011896 Wetherspoons 6 High Street Aberdare CF44 7AA Retail - Pub 2009691 Archibald Simpson 5 Castle Street Aberdeen AB11 5BQ Retail - Pub 2003453 BAA - Aberdeen Aberdeen Airport Aberdeen AB21 7DU Transport - Small Airport 2009128 Britannia Hotel Malcolm Road Aberdeen AB21 9LN Retail - Pub 2014519 First Scot Rail - Aberdeen Guild St Aberdeen AB11 6LX Transport - Local rail station 2009345 Grays Inn Greenfern Road Aberdeen AB16 5PY Retail - Pub 2011456 Liquid Bridge Place Aberdeen AB11 6HZ Retail - Pub 2012139 Lloyds No.1 (Justice Mill) Justice Mill Aberdeen AB11 6DA Retail - Pub 2007205 McDonald's - 1341 Asda Aberdeen Garthdee Road Aberdeen AB10 7BA Retail - Fast Food 2006333 McDonald's - 398 Aberdeen 1 117 Union Street ABERDEEN AB11 6BH Retail - Fast Food 2006524 McDonald's - 618 Bucksburn Inverurie Road ABERDEEN AB21 9LZ Retail - Fast Food 2006561 McDonald's - 663 Bridge Of Don Broadfold Road ABERDEEN AB23 8EE Retail - Fast Food 2010111 Menzies Farburn Terrace Aberdeen AB21 7DW Retail - Pub 2007684 Triplekirks Schoolhill Aberdeen AB12 4RR Retail - Pub 2002538 Swallow Thainstone House Hotel Inverurie Aberdeenshire AB51 5NT Hotels - 4/5 Star Hotel with full coverage 2002546 Swallow Waterside Hotel Fraserburgh -

View Catalogue

BOW WINDOWS BOOKSHOP 175 High Street, Lewes, Sussex, BN7 1YE T: +44 (0)1273 480 780 F: +44 (0)1273 486 686 [email protected] bowwindows.com CATALOGUE TWO HUNDRED AND ELEVEN Literature - First Editions, Classics, Private Press 1 - 89 Children's and Illustrated Books 90 - 107 Natural History 108 - 137 Maps 138 - 154 Travel and Topography 155 - 208 Art and Architecture 209 - 238 General Subjects - History, Theology, Militaria 239 - 264 Cover images – nos. 93 & 125 All items are pictured on our website and further images can be emailed on request. All books are collated and described as carefully as possible. Payment may be made by cheque, drawn on a sterling account, Visa, MasterCard or direct transfer to Account No. 40009652 at HSBC Bank, Eastbourne, sort code 40-20-69. Our IBAN code is GB02 HBUK40206940009652; SWIFTBIC is MIDL GB22. Postage will be charged at cost. Foreign orders will be sent by airmail unless requested otherwise. Our shop hours are 9.30 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday to Saturday; an answerphone operates outside of these times. Items may also be ordered via our website. Ric Latham and Jonathan Menezes General Data Protection Regulation We hold on our computer our customers names and addresses, and in some cases phone numbers and email addresses. We do not share this information with third parties. We assume that you will be happy to continue to receive these catalogues and for us to hold this information; should you wish to change anything or come off our mailing list please let us know. LITERATURE FIRST EDITIONS, CLASSICS, PRIVATE PRESS 1. -

Document Template

Chatterbooks Fireside Fiction Activity Pack Reading and activity ideas for your Chatterbooks group Fireside Fiction About this pack Here are some fabulous Fireside Fiction titles for you to enjoy with your group, as well as ideas for discussion and activities. You’ll find stories about Christmas and winter; stories to take you to fantasy worlds and adventures, far away from the wind and the rain and the cold; stories which have been shared through generations; stories to curl up with by the fire , and stories to tell each other when you’re gathered round the fireside – or a cosy radiator. This Fireside Fiction pack is brought to you by The Reading Agency and their Children’s Reading Partner publisher partners. Chatterbooks [ www.chatterbooks.org.uk] is a reading group programme for children aged 4 to 14 years. It is coordinated by The Reading Agency and its patron is author Dame Jacqueline Wilson. Chatterbooks groups run in libraries and schools, supporting and inspiring children’s literacy development by encouraging them to have a really good time reading and talking about books. The Reading Agency is an independent charity working to inspire more people to read more through programmes for adults, young people and Children – including the Summer Reading Challenge, and Chatterbooks. See www.readingagency.org.uk Children’s Reading Partners is a national partnership of children’s publishers and libraries working together to bring reading promotions and author events to as many children and young people as possible. Contents 3 Fireside Fiction: Ideas for discussion, activities and story sharing: Warm up 4 Fireside Fiction: Longer activities 6 Fireside fiction for your Christmas tree 7 Fireside Fiction: the Books! 18 More Fireside Fiction reading ideas 19 A few tips for your Fireside Fiction story sharing Page 2 of 19 Fireside Fiction: Ideas for discussion, activities and story sharing Warm up Have a go at these two word puzzles. -

St Patrick's Recommended Reading List

St Patrick’s Recommended Reading list At St Patrick’s we want your children to be confident readers and more importantly enjoy reading! We have put together a list of books that we feel your child will enjoy and suitable for their reading level! Red, Yellow, Blue, Green and Orange bands (Working within Foundation stage or stage 1) Title Author Each Peach Pear Plum Janet and Allen Ahlberg Mr Gumpy’s Outing John Burningham Rosie’s Walk’ Pat Hutchins The Very Hungry Caterpillar’ Eric Carle Mister Magnolia’ Quentin Blake Owl Babies’ Martin Waddel Alfie Gets in First’ Shirley Hughes Elmer David McKee Brown Bear, Brown Bear what do you see? Bill Martin and Eric Carle We’re going on a bear hunt Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury My cat likes to hide in boxes’ Lynley Dodd ‘Peepo’ Janet and Allen Ahlberg Meg and Mog’ Helen Nicoll and Jan Pienkowski Dear Zoo’ Rod Campbell Kipper Mick Inkpen The Pig in the Pond’ Martin Waddell and Jill Barton Oh Dear!’ Rod Campbell Where’s Spot’ Eric Hill This is the Bear’ and ‘This is the Bear and Sarah Hayes and Helen Craig the Picnic Lunch’ Not Now Bernard’ David McKee Where the Wild Things Are’ Maurice Sendak Gorilla Anthony Browne A Dark, Dark Tale’ Ruth Brown 1 Turquoise, Purple, Gold and silver bands (Working within stages 2 or 3) Frog and Toad are Friends’ Arnold Lobel and other Frog and Toad stories Mrs Plug the Plumber’ and Allan Ahlberg other stories in this series Solomon’s Secret’ Saviour Pirotta Peace at last Jill Murphy The Tiger who came to tea’ Judith Kerr Hairy Maclary from Lynley Dodd Donoldson’s -

The Diary of Heinrich Witt

The Diary of Heinrich Witt Volume 2 Edited by Ulrich Mücke LEIDEN | BOSTON Ulrich Muecke - 9789004307247 Downloaded from Brill.com10/10/2021 09:30:38PM via free access [1] [2] Volume the second Commenced in Lima October the 9th 1867 Tuesday, 24th of January 1843. At 10 Oclock a.m. I started for Mr. Schutte’s silver mine of Orcopampa, my party was rather numerous; it consisted of course of myself on mule back with a led beast for change, the muleteer Delgado, his lad Mateo, both mounted, an Indian guide on foot named Condor, and seven mules laden with various articles for the mine as well as some provisions for myself, two or three fowls, half a sheep, potatoes, bread, salt, and sugar, also some sperm candles, and a metal candlestick. The mules carried each a load from eight to nine arrobes, besides four arrobes the weight of the gear and trappings. I may as well say en passant that I carried the above various articles of food because I had been assured that on this route I should find few eatables. I, accustomed to the ways and habits of the Sierra, saw nothing particular in the costume of my companion, nevertheless I will describe it, the muleteers wore ordinary woollen trowsers, and jackets, a woollen poncho over the shoulders, Chilian boots to the legs, shoes to their feet, but with only a single spur, on the principle that if one side of the animal moved the other could not be left behind; their head covering was a Guayaquil straw hat, underneath it Delgado wore a woollen cap, also round his neck a piece [_] jerga, for the purpose of blind folding his beasts when loading [_] a second piece round his waist the two ends of which [_] [3] and preserved his trowsers. -

Xhviti Nvf 'Hdvhohohlfw M3SH3QMV NYI1SIHH3 SNVH Sdiulod 9 SHOOH SM3HQ1IH3

XHVIti NVf 'HdVHOHOHlfW M3SH3QMV NYI1SIHH3 SNVH SDIUlOd 9 SHOOH SM3HQ1IH3 F" 2 BOOKS FOR KEEPS No. 25 MARCH 1984 Lisbeth Zwerger 21 Cover Book Meet our cover artist On our cover this month we Opinion: Andersen and the 22 feature an illustration from Editor's Page 3 The Swineherd, a picture News and comment from the editor English Brian Alderson on English translations book version of the Andersen and illustrations of Andersen fairy tale by artist Lisbeth Children's Books and Zwerger. (Neugebauer Press, Politics News 0907234127, £3.95 from Robert Leeson puts the topic in 4 24 perspective A. and C. Black). We are James Watson and Jan Needle speaking 6 grateful to A. and C. Black for personally help in using this illustration. The roundel used on the Hans Reviews — Paperback 8 — the magazine of the School Bookshop Association Andersen pages is from the MARCH 1984 No. 25 wood engraving by Gwen Authorgraph No. 25 12 Raverat for Four Tales, Jan Mark ISSN: 0143-909X Editor: Pat Triggs translated by R. P. Keigwin, How to... Get Moving on a 14 Managing Editor: Richard Hill C.U.P. (1935). Designer: Alec Davis It and the Punch cartoon on Book Day Typesetting by: Curtis Typesetting, Ideas for getting started with planning Gloucester page 16 appear in Brian Printed by: Surrey Fine Art Press Ltd, Alderson's pamphlet Hans New York Diary 15 Red hi It, Surrey Christian Andersen and his The latest dispatch from John Mason ©School Bookshop Association 1984 Eventyr in England. The Hans Andersen Award 16 can be obtained Patricia Crampton writes about judging on subscription by sending a cheque or an international award postal order to the Subscription Secretary, SBA, 1 Effingham Road, Lee, London Sound and Vision 17 SE12 8NZ. -

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and Their Origins

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and their origins © David A. Hayes and Camden History Society, 2020 Introduction Listed alphabetically are In 1853, in London as a whole, there were o all present-day street names in, or partly 25 Albert Streets, 25 Victoria, 37 King, 27 Queen, within, the London Borough of Camden 22 Princes, 17 Duke, 34 York and 23 Gloucester (created in 1965); Streets; not to mention the countless similarly named Places, Roads, Squares, Terraces, Lanes, o abolished names of streets, terraces, Walks, Courts, Alleys, Mews, Yards, Rents, Rows, alleyways, courts, yards and mews, which Gardens and Buildings. have existed since c.1800 in the former boroughs of Hampstead, Holborn and St Encouraged by the General Post Office, a street Pancras (formed in 1900) or the civil renaming scheme was started in 1857 by the parishes they replaced; newly-formed Metropolitan Board of Works o some named footpaths. (MBW), and administered by its ‘Street Nomenclature Office’. The project was continued Under each heading, extant street names are after 1889 under its successor body, the London itemised first, in bold face. These are followed, in County Council (LCC), with a final spate of name normal type, by names superseded through changes in 1936-39. renaming, and those of wholly vanished streets. Key to symbols used: The naming of streets → renamed as …, with the new name ← renamed from …, with the old Early street names would be chosen by the name and year of renaming if known developer or builder, or the owner of the land. Since the mid-19th century, names have required Many roads were initially lined by individually local-authority approval, initially from parish named Terraces, Rows or Places, with houses Vestries, and then from the Metropolitan Board of numbered within them. -

Blue Plaques in Bromley

Blue Plaques in Bromley Blue Plaques in Bromley..................................................................................1 Alexander Muirhead (1848-1920) ....................................................................2 Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807-1889)...................................................3 Brass Crosby (1725-1793)...............................................................................4 Charles Keeping (1924-1988)..........................................................................5 Enid Blyton (1897-1968) ..................................................................................6 Ewan MacColl (1915-1989) .............................................................................7 Frank Bourne (1855-1945)...............................................................................8 Harold Bride (1890-1956) ................................................................................9 Heddle Nash (1895-1961)..............................................................................10 Little Tich (Harry Relph) (1867-1928).............................................................11 Lord Ted Willis (1918-1992)...........................................................................12 Prince Pyotr (Peter) Alekseyevich Kropotkin (1842-1921) .............................13 Richmal Crompton (1890-1969).....................................................................14 Sir Geraint Evans (1922-1992) ......................................................................15 Sir -

Property Ref Rateable Value Address Address ADDRESS Post Code Surname App Applied Relief Rlf Cd

Disc Rel SBR Mand ·Addtnl Property Ref Rateable Value Address Address ADDRESS Post Code Surname App Applied Relief Rlf Cd 102 CAMDEN HIGH 00641010210011 64500 GND F LONDON NW1 0LU MUCHO MAS LTD FRESH STREET 00895006510018 18000 BST & GND FS 65 GRAYS INN ROAD LONDON WC1X 8TL FISHER LONDON LTD FRESH RETAIL 285-287 GRAYS INN C A MEDICAL (LONDON) 00895028530012 31500 BST PT & GND F LONDON WC1X 8QF FRESH ROAD LIMITED 12SBR3 GREVILLE 01182001230014 58000 BST & GND FS LONDON EC1N 8SB JERKKIES LIMITED FRESH STREET 01232019000006 21000 190 DRURY LANE LONDON WC2B 5QD V&ART UK FRESH RETAIL SARA BESPOKE CURTAINS 05006050910018 14250 BST & GND FS 509 FINCHLEY ROAD LONDON NW3 7BB FRESH RETAIL LTD 0122400021001A 24250 GND F L 2 NEALS YARD LONDON WC2H 9DP 26 GRAINS LIMITED FRESH RETAIL THE LONDON EARLY 0094100520000A 22000 54A WHITFIELD STREET LONDON W1T 4ER DR2000 MAND80 YEARS FOUNDATION CHRISTCHURCH 00000290107013 17500 CHRISTCHURCH HILL LONDON NW3 1JH LBC - EA200CE020 DIS20 MAND80 SCHOOL 00000290108016 22000 HOLY TRINITY SCHOOL COLLEGE CRESCENT LONDON NW3 5DN LBC - EA204CE020 DIS20 MAND80 HOLY TRINITY PRIMARY 00000290116008 20500 HARTLAND ROAD LONDON NW1 8DB LBC - EA205CE020 DIS20 MAND80 SCHOOL 00000290120003 203000 WILLIAM ELLIS SCHOOL HIGHGATE ROAD LONDON NW5 1QS LBC - EA315CE020 DIS20 MAND80 00000290123016 36250 ST JOSEPHS SCHOOL MACKLIN STREET LONDON WC2B 5NA LBC - EA215CE020 DIS20 MAND80 00000290137004 47250 ST DOMINICS SCHOOL SOUTHAMPTON ROAD LONDON NW5 4JS LBC - EA213CE020 DIS20 MAND80 HAMPSTEAD PAROCHIAL 00150099920008 34000 HOLLY BUSH VALE -

Zenker, Stephanie F., Ed. Books For

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 415 506 CS 216 144 AUTHOR Stover, Lois T., Ed.; Zenker, Stephanie F., Ed. TITLE Books for You: An Annotated Booklist for Senior High. Thirteenth Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-0368-5 ISSN ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 465p.; For the 1995 edition, see ED 384 916. Foreword by Chris Crutcher. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 03685: $16.95 members, $22.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC19 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Adolescents; Annotated Bibliographies; *Fiction; High School Students; High Schools; *Independent Reading; *Nonfiction; *Reading Interests; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Motivation; Recreational Reading; Thematic Approach IDENTIFIERS Multicultural Materials; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Designed to help teachers, students, and parents identify engaging and insightful books for young adults, this book presents annotations of over 1,400 books published between 1994 and 1996. The book begins with a foreword by young adult author, Chris Crutcher, a former reluctant high school reader, that discusses what books have meant to him. Annotations in the book are grouped by subject into 40 thematic chapters, including "Adventure and Survival"; "Animals and Pets"; "Classics"; "Death and Dying"; "Fantasy"; "Horror"; "Human Rights"; "Poetry and Drama"; "Romance"; "Science Fiction"; "War"; and "Westerns and the Old West." Annotations in the book provide full bibliographic information, a concise summary, notations identifying world literature, multicultural, and easy reading title, and notations about any awards the book has won.