Exiled to English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literature (LIT) 1

Literature (LIT) 1 LITERATURE (LIT) LIT 113 British Literature i (3 credits) LIT 114 British Literature II (3 credits) LIT 115 American Literature I (3 credits) LIT 116 Amercian Literature II (3 credits) LIT 132 Introduction to Literary Studies (3 credits) This course prepares students to understand literature and to articulate their understanding in essays supported by carefully analyzed evidence from assigned works. Major genres and the literary terms and conventions associated with each genre will be explored. Students will be introduced to literary criticism drawn from a variety of perspectives. Course Rotation: Fall. LIT 196 Topics in Literature (3 credits) LIT 196A Topic: Images of Nature in American Literature (3 credits) LIT 196B Topic: Gothic Fiction (3 credits) LIT 196C Topic: American Detective Fiction (3 credits) LIT 196D Topic: The Fairy Tale (3 credits) LIT 196H Topic: Literature of the Supernatural (4 credits) LIT 196N Topic: American Detective Fiction for Nactel Program (4 credits) LIT 200C Global Crossings: Challenge & Change in Modern World Literature - Nactel (4 credits) Students in the course will read literature from a range of international traditions and will reach an understanding and appreciation of the texts for the ways that they connect and diverge. The social and historical context of the works will be explored and students will take from the course some understanding of the environments that produced the texts. LIT 200G Topic: Pulitzer Prize Winning Novels-American Life (3 credits) LIT 200H Topic: Poe and Hawthorne (3 credits) LIT 201 English Drama 900-1642 (3 credits) LIT 202 History of Film (3 credits) The development of the film from the silent era to the present. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Historical Fiction

Book Group Kit Collection Glendale Library, Arts & Culture To reserve a kit, please contact: [email protected] or call 818-548-2021 New Titles in the Collection — Spring 2021 Access the complete list at: https://www.glendaleca.gov/government/departments/library-arts-culture/services/book-groups-kits American Dirt by Jeannine Cummins When Lydia Perez, who runs a book store in Acapulco, Mexico, and her son Luca are threatened they flee, with countless other Mexicans and Central Americans, to illegally cross the border into the United States. This page- turning novel with its in-the-news presence, believable characters and excellent reviews was overshadowed by a public conversation about whether the author practiced cultural appropriation by writing a story which might have been have been best told by a writer who is Latinx. Multicultural Fiction. 400 pages The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek by Kim Michele Richardson Kentucky during the Depression is the setting of this appealing historical fiction title about the federally funded pack-horse librarians who delivered books to poverty-stricken people living in the back woods of the Appalachian Mountains. Librarian Cussy Mary Carter is a 19-year-old who lives in Troublesome Creek, Kentucky with her father and must contend not only with riding a mule in treacherous terrain to deliver books, but also with the discrimination she suffers because she has blue skin, the result of a rare genetic condition. Both personable and dedicated, Cussy is a sympathetic character and the hardships that she and the others suffer in rural Kentucky will keep readers engaged. -

A.P. Literature ~ Short Story Project Mr. Bills Welcome to the Library! For

A.P. Literature ~ Short Story Project Mr. Bills Welcome to the library! For this task, we have several sources for you to use. Our Story Collection is located by the main library doors. Story collections are books of collected stories either by author (example, SC KIN for a book of short stories by Stephen King) or by theme (Best American Science Fiction, Gothic tales, crime stories). We’ve pulled some for you; feel free to take a look. To find an author or short story of literary merit: Using the online catalog: Do an author search in the catalog. Ex. hemingway, ernest Look for the title of the short story or titles like "Collected Works," "Complete Works," or "Selected Works." Some records will list the stories contained in the collection. Another way to locate short stories is to see if they are part of an anthology or other collection. Try a keyword in the online catalog Ex. edgar allan poe AND stories tell tale heart Using Online Sources: Databases: Poetry and Short Story Center– search by author or title. Icons help you easily identify the type of result (short story, review, academic journal, periodical, book, etc.). Read the short description in the result to determine if it works for your search, i.e. is a short story to read). Literary Reference Center- search by author or short story titles. Results may be Books, Reviews, Academic Journals, or Periodicals. For short stories published in magazines, you want to take a close look at the results labeled Periodicals. Reminder – username and passwords are required to access from home (U = lcpsh, PW = high) Websites: The New Yorker – use the search box (upper right); also use the Archive link The Atlantic – search for story or author Donahue 2016 Harper’s - Be sure your results are identified as Fiction for this project as Harper’s has Articles, Essays, Stories, etc. -

About This Volume Robert C

About This Volume Robert C. Evans 7KH 8QLWHG 6WDWHV KDV ORQJ SULGHG LWVHOI RQ EHLQJ D QDWLRQ RI immigrants, and certainly immigrants or their immediate descendants have long made valuable contributions to the nation’s literature. :DYHDIWHUZDYHRILPPLJUDQWVIURPPDQ\QDWLRQV²DW¿UVWPDLQO\ from Europe, but then (more recently), mostly from other continents RUUHJLRQV²KDYHDGGHGERWKWRWKHSRSXODWLRQDQGWRWKHFXOWXUHRI the country. Immigrant writers and their children have brought with them both memories and dreams, both experiences and aspirations. Sometimes they have found their status as immigrants exciting; sometimes they have found it exasperating; usually their attitudes have been mixed. In the process of sharing their thoughts and H[SHULHQFHVZLWKUHDGHUVRI¿FWLRQWKH\KDYHRIWHQHQULFKHGERWK American literature and the English language. In her introductory essay to this volume, Natalie Friedman offers helpful reminders of the history of the often close relations EHWZHHQ LPPLJUDQWV DQG VKRUW ¿FWLRQ 6KH VXJJHVWV WKDW VKRUW VWRULHV²EHFDXVH RI WKHLU VLPXOWDQHRXV EUHYLW\ DQG SRVVLELOLWLHV IRU FRPSOH[LW\²KDYH IUHTXHQWO\ EHHQ LGHDO IRUPV IRU LPPLJUDQW ZULWHUV6WRULHVFDQRIWHQEHZULWWHQPRUHTXLFNO\DQGUHDGPRUH ZLGHO\ WKDQ QRYHOV DQG PDQ\ KDYH DSSHDUHG ¿UVW LQ SHULRGLFDOV especially designed for immigrant readers. Friedman discusses the early twentieth-century Jewish writer Abraham Cahan as a good example of larger trends. In so doing, she also provides valuable background information about the roots of American immigrant VKRUW ¿FWLRQ LQ WKH ZULWLQJV RI LPPLJUDQWV ZKR RIWHQ FDPH IURP Europe. A similar emphasis on an earlier writer from Europe appears LQ6ROYHLJ=HPSHO¶VLOOXPLQDWLQJHVVD\RQWKHVKRUW¿FWLRQRIWKH Norwegian American writer O. E. Rølvaag. As Zempel notes, writers and their works “do not exist in isolation; instead, they are embedded in a wide variety of historical situations. -

A Kachruvian Study of Ha Jin's Chineseness In

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies September 2016: 195-220 DOI: 10.6240/concentric.lit.2016.42.2.11 “All the Guns Must Have the Same Caliber”: A Kachruvian Study of Ha Jin’s Chineseness in “Winds and Clouds over a Funeral” José R. Ibáñez Department of Philology University of Almeria, Spain Abstract This article analyzes Ha Jin’s “Winds and Clouds over a Funeral” within a Kachruvian framework. Firstly, it examines Braj B. Kachru’s concepts of “contact literature” and the “bilingual’s creativity” in that both of these undermine the traditional homogeneity of a monolingual conceptualization of the English language. I then offer an overview of Kachru’s taxonomical model as a means of explaining the cultural, grammatical and linguistic alterations in the creativity of bilinguals, especially that of writers who use English as a second language. In this regard, and bearing in mind Haoming Gong’s concept of “translation literature,” I explore Ha Jin’s “Winds and Clouds over a Funeral” in terms of the linguistic processes and nativization strategies employed by this Chinese-American author in order to transfer cultural aspects from his native language, Chinese. Through this I aim to reveal and describe the hybrid nature of the work of Ha Jin, a writer who I believe is paving the way for a reassessment of Asian-American fiction in the United States. Keywords Kachruvian framework, bilingual’s creativity, contact literatures, hybridity, Chinese English I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions. The research on this paper was supported by the project CEIPatrimonio, University of Almeria. -

Award-Winning Writer Ha Jin Reads at UNH Nov. 3

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Media Relations UNH Publications and Documents 10-26-2006 Award-Winning Writer Ha Jin Reads At UNH Nov. 3 Lori Wright Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/news Recommended Citation Wright, Lori, "Award-Winning Writer Ha Jin Reads At UNH Nov. 3" (2006). UNH Today. 979. https://scholars.unh.edu/news/979 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the UNH Publications and Documents at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Relations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Award-Winning Writer Ha Jin Reads At UNH Nov. 3 9/18/17, 155 PM Award-Winning Writer Ha Jin Reads At UNH Nov. 3 Contact: Lori Wright 603-862-0574 UNH Media Relations October 26, 2006 DURHAM, N.H. -- The University of New Hampshire English Department is proud to present a reading by prize-winning author Ha Jin as part of its 2006-2007 Writers Series Friday, November 3, 2006, at 6 p.m. in Murkland Hall, room 115, on the Durham campus. Jin’s reading is free and open to the public. Ha Jin emigrated from China in the early 1990s. He was on scholarship at Brandeis University when the 1989 Tiananmen incident happened and remained in the United States after earning his Ph.D. in 1992. His first book of poems, Between Silences, was published in 1990. -

View with Ha Jin

WRITING SHORT FICTION FROM EXILE. AN INTER- VIEW WITH HA JIN Jose Ramón Ibáñez Ibáñez, Universidad de Almería15 Email: jibanez@ual .es During the last two decades, Jīn Xuĕfēi, who goes under the pen–name of Ha Jin, has emerged as one of the most prominent Asian–American writers in America, with works in fiction, poetry and essays dealing with the Chinese experience in China and the U.S. Born in 1956 in the Chinese province of Liaoning, Ha Jin’s life has been strongly marked by po- litical and sociological events occurring in contemporary China. His father was an officer in the Red Army who was transferred around various provinces for years. This continuous change of residence gave young Jin the opportunity to discover remote regions, meet people and get acquainted with Chinese traditions and customs. Ha Jin was ten years old when Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution, which aimed at removing capitalism and Chinese traditions by way of the strict implementation of communism. Colleges were closed for ten years and many young people became Red Guards, an armed revolutionary youth organization aiming to eradicate the ‘four Olds’ – Old Customs, Old Culture, Old Habits and Old Ideas – which were described as anti– proletarian. At the age of thirteen, Ha Jin joined the People’s Liberation Army as a way of leaving home as he declared in different interviews (Gardner 2000; Weinberger, 2007; Fay 2009). While in the army, he worked as a telegrapher, a post which allowed him some free time to read literature and educate himself. He left the army in 1975 and worked for three years in a railway company. -

AMERIŠKA DRŽAVNA NAGRADA ZA KNJIŽEVNOST Nagrajene Knjige, Ki

AMERIŠKA DRŽAVNA NAGRADA ZA KNJIŽEVNOST Nagrajene knjige, ki jih imamo v naši knjižnični zbirki, so označene debelejše: Roman/kratke zgodbe 2018 Sigrid Nunez: The Friend 2017 Jesmyn Ward: Sing, Unburied, Sing 2016 Colson Whitehead THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD 2015 Adam Johnson FORTUNE SMILES: STORIES 2014 Phil Klay REDEPLOYMENT 2013 James McBrid THE GOOD LORD BIRD 2012 Louise Erdrich THE ROUND HOUSE 2011 Jesmyn Ward SALVAGE THE BONES 2010 Jaimy Gordon LORD OF MISRULE 2009 Colum McCann LET THE GREAT WORLD SPIN (Naj se širni svet vrti, 2010) 2008 Peter Matthiessen SHADOW COUNTRY 2007 Denis Johnson TREE OF SMOKE 2006 Richard Powers THE ECHO MAKER 2005 William T. Vollmann EUROPE CENTRAL 2004 Lily Tuck THE NEWS FROM PARAGUAY 2003 Shirley Hazzard THE GREAT FIRE 2002 Julia Glass THREE JUNES 2001 Jonathan Franzen THE CORRECTIONS (Popravki, 2005) 2000 Susan Sontag IN AMERICA 1999 Ha Jin WAITING (Čakanje, 2008) 1998 Alice McDermott CHARMING BILLY 1997 Charles Frazier COLD MOUNTAIN 1996 Andrea Barrett SHIP FEVER AND OTHER STORIES 1995 Philip Roth SABBATH'S THEATER 1994 William Gaddis A FROLIC OF HIS OWN 1993 E. Annie Proulx THE SHIPPING NEWS (Ladijske novice, 2009; prev. Katarina Mahnič) 1992 Cormac McCarthy ALL THE PRETTY HORSES 1991 Norman Rush MATING 1990 Charles Johnson MIDDLE PASSAGE 1989 John Casey SPARTINA 1988 Pete Dexter PARIS TROUT 1987 Larry Heinemann PACO'S STORY 1986 Edgar Lawrence Doctorow WORLD'S FAIR 1985 Don DeLillo WHITE NOISE (Beli šum, 2003) 1984 Ellen Gilchrist VICTORY OVER JAPAN: A BOOK OF STORIES 1983 Alice Walker THE COLOR PURPLE -

For Your Convenience, Here Is a List of the English Department Faculty, Their Offices, Phone Extensions, and Office Hours for Spring ‘12

Please note: For your convenience, here is a list of the English Department faculty, their offices, phone extensions, and office hours for Spring ‘12. Make sure you speak with your advisor well in advance of Spring ’12 Registration (which begins April 9). If office hours are not convenient you can always make an appointment. OFFICE HOURS OFFICE INSTRUCTOR EXT. Spring 2012 LOCATION Barnes, Alison W 2:00-3:00 5153 PMH 420 Bernard, April M 4:00-5:00; W 12:00-1:00 & by appt. 8396 PMH 317 Black, Barbara W 10:00-11:00; Th 11:00-12:00 5154 PMH 316 Bonneville, Francois T/W 2:30-4:30 & by appt. 5181 PMH 320E Boshoff, Phil M 2:00-3:30; W/F 12:00-1:00 & by appt. 5155 PMH 309 Boyers, Peg W 2:00-5:00 and by appt. 5186 PMH 327 Boyers, Robert W 10:00-12:30 & 2:30-5:30 5156 PMH 325 Breznau, Anne T 5:15-6:15; Th 2:30-3:30 & by appt. 8393 PMH 320W Cahn, Victor T/Th 7:30-8:00; 11:00-11:30 AM and by appt. 5158 PMH 311 Casey, Janet W 11:00-12:00 & by appt. 5183 PMH 315 Devine, Joanne T/Th 11:15-12:15; W 1:30-3:00 & by appt. 5162 PMH 318 Enderle, Scott M/W/F 11:15-12:15 5191 PMH 332 Fogle, Andy M 4:00-5:00 5187 PMH 327 Glaser, Ben T/Th 3:30-4:45 5185 PMH 306 Gogineni, Bina T/Th 12:30-2:00 5165 PMH 334 Golden, Catherine M 2:00-4:00 & by appt. -

Pulitzer Prize Bookmark.Pub

Pulitzer Prize Winners Pulitzer Prize Winners Pulitzer Prize Winners Pulitzer Prize Winners for Fiction for Fiction for Fiction for Fiction 2006: March 2006: March 2006: March 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks by Geraldine Brooks by Geraldine Brooks by Geraldine Brooks 2005: Gilead 2005: Gilead 2005: Gilead 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson by Marilynne Robinson by Marilynne Robinson by Marilynne Robinson 2004: The Known World 2004: The Known World 2004: The Known World 2004: The Known World by Edward P. Jones by Edward P. Jones by Edward P. Jones by Edward P. Jones 2003: Middlesex 2003: Middlesex 2003: Middlesex 2003: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides by Jeffrey Eugenides by Jeffrey Eugenides by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002: Empire Falls 2002: Empire Falls 2002: Empire Falls 2002: Empire Falls by Richard Russo by Richard Russo by Richard Russo by Richard Russo 2001: The Amazing 2001: The Amazing 2001: The Amazing 2001: The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier Adventures of Kavalier Adventures of Kavalier Adventures of Kavalier & Clay & Clay & Clay & Clay by Michael Chabon by Michael Chabon by Michael Chabon by Michael Chabon 2000: Interpreter of 2000: Interpreter of 2000: Interpreter of 2000: Interpreter of Maladies Maladies Maladies Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri by Jhumpa Lahiri by Jhumpa Lahiri by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999: The Hours 1999: The Hours 1999: The Hours 1999: The Hours by Michael Cunningham by Michael Cunningham by Michael Cunningham by Michael Cunningham 1998: American Pastoral 1998: American Pastoral 1998: American Pastoral 1998: American Pastoral -

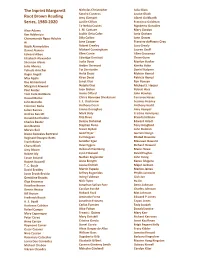

The Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series, 1980-2020

The Inprint Margarett Nicholas Christopher Julia Glass Sandra Cisneros Louise Glück Root Brown Reading Amy Clampitt Albert Goldbarth Series, 1980-2020 Lucille Clifton Francisco Goldman Ta-Nehisi Coates Rigoberto González Alice Adams J. M. Coetzee Mary Gordon Kim Addonizio Judith Ortiz Cofer Jorie Graham Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Billy Collins John Graves Ai Jane Cooper Francine duPlessix Gray Rabih Alameddine Robert Creeley Lucy Grealy Daniel Alarcón Michael Cunningham Lauren Groff Edward Albee Ellen Currie Allen Grossman Elizabeth Alexander Edwidge Danticat Thom Gunn Sherman Alexie Lydia Davis Marilyn Hacker Julia Alvarez Amber Dermont Kimiko Hahn Yehuda Amichai Toi Derricotte Daniel Halpern Roger Angell Anita Desai Mohsin Hamid Max Apple Kiran Desai Patricia Hampl Rae Armantrout Junot Díaz Ron Hansen Margaret Atwood Natalie Diaz Michael S. Harper Paul Auster Joan Didion Robert Hass Toni Cade Bambara Annie Dillard John Hawkes Russell Banks Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni Terrance Hayes John Banville E. L. Doctorow Seamus Heaney Coleman Barks Anthony Doerr Anthony Hecht Julian Barnes Emma Donoghue Amy Hempel Andrea Barrett Mark Doty Cristina Henríquez Donald Barthelme Rita Dove Brenda Hillman Charles Baxter Denise Duhamel Edward Hirsch Ann Beattie Stephen Dunn Tony Hoagland Marvin Bell Stuart Dybek John Holman Diane Gonzales Bertrand Geoff Dyer Garrett Hongo Reginald Dwayne Betts Esi Edugyan Khaled Hosseini Frank Bidart Jennifer Egan Maureen Howard Chana Bloch Dave Eggers Richard Howard Amy Bloom Deborah Eisenberg Marie Howe Robert Bly Lynn Emanuel David Hughes Eavan Boland Nathan Englander John Irving Robert Boswell Anne Enright Kazuo Ishiguro T. C. Boyle Louise Erdrich Major Jackson David Bradley Martin Espada Marlon James Lucie Brock-Broido Jeffrey Eugenides Phyllis Janowitz Geraldine Brooks Irving Feldman Gish Jen Olga Broumas Nick Flynn Ha Jin Rosellen Brown Jonathan Safran Foer Denis Johnson Dennis Brutus Carolyn Forché Charles Johnson Bill Bryson Richard Ford Mat Johnson Frederick Busch Aminatta Forna Edward P.