Chapter Six Anti-Poverty Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Message from the Mayor Hello All This Is My First Town Message and I Hope It Keeps You up to Date with Town News and Events

Edition 28 : July 2012 Message from the Mayor Hello All This is my first Town Message and I hope it keeps you up to date with Town news and events. Good Times It was marvellous to see virtually all our Town out to say farewell to the Olympic Torch after a fabulous day of sporting and music activities. This was followed, 2 weeks later, by the Queens Jubilee celebrations with 15 street parties (some overcoming torrential rain), Beating the Bounds, a picnic in the park and 2 tree planting ceremonies. The Mayfair in its new location was hailed as a success and the Regatta too was a resounding success, despite the weather. A new theatrical and music group Page2Stage started in late June. Chris, Andy, Paul and Niall from the Cecil Arms who while breaking a Guinness record for playing darts for over 41 hours raised a staggering £3000 for Parkinson‟s Disease UK. Two new shops opened – More than Art and the Original Factory Shop. Our shopping centre is thriving and has only 4 empty shops which is a very different case to many other towns in Cornwall. Not so good We live in an area with an extremely low crime rate, so it is sad to note that in June we have some less sociable members of our town who feel emptying and stealing grit bins is enjoyable. What it means for us is we have to pay more taxes to put things back to ensure we are ready for winter. Getting better Our Town Council has regained its Quality Status. -

Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS CORNWALL COUNCIL VOTING AREA Referendum on the United Kingdom's membership of the European Union 1. A referendum is to be held on THURSDAY, 23 JUNE 2016 to decide on the question below : Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union? 2. The hours of poll will be from 7am to 10pm. 3. The situation of polling stations and the descriptions of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows : No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 301 STATION 2 (AAA1) 1 - 958 CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 301/1 STATION 1 (AAM4) 1 - 212 THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 302 CUDDRA W I HALL (AAA2) 1 - 430 BUCKLERS LANE HOLMBUSH ST AUSTELL PL25 3HQ 303 BETHEL METHODIST CHURCH (AAB1) 1 - 1,008 BROCKSTONE ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DW 304 BISHOP BRONESCOMBE SCHOOL (AAB2) 1 - 879 BOSCOPPA ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DT KATE KENNALLY Dated: WEDNESDAY, 01 JUNE, 2016 COUNTING OFFICER Printed and Published by the COUNTING OFFICER ELECTORAL SERVICES, ST AUSTELL ONE STOP SHOP, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 305 SANDY HILL ACADEMY (AAB3) 1 - 1,639 SANDY HILL ST AUSTELL PL25 3AW 306 STATION 2 (AAG1) 1 - 1,035 THE COMMITTEE ROOM COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK ROAD PL25 5DR 306/1 STATION 1 (APL3) 1 - 73 THE COMMITTEE ROOM CORNWALL COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK -

Cornwall Residency January 2016

Cornwall Residency January 2016 Overview After an extensive Residency during Spring 2015, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra was delighted to return to Cornwall for a smaller- scale series of concerts, workshops and events in January 2016. The residency visited over 20 locations with an exciting programme full of creativity, discovery and learning that spanned eight days, delivered by 10 professional musicians. Working closely with Cornwall Music Education Hub the orchestra sought to engage new schools, try out new activities in response to local need and build on existing relationships before the full orchestra returns for a large-scale programme of events 2017. Events and Activities The programme saw BSO Bash (percussion) and a BSO String Quartet tour primary and secondary schools including Newlyn Primary School, St Mary’s C of E Primary School and Pendeen School, Penzance, Bishop Cornish Primary School, Saltash, Dunloe Primary School, Liskeard and Budehaven Community School, Bude. BSO Associates – musicians in the community, offered training for teachers and music support in primary and secondary schools including Charlestown Primary School, Carylon Bay and St Neot Community Primary School, Liskeard. 340 students from Secondary Schools across the county attended a GCSE curriculum concert at Hall for Cornwall, presented by BSO Associate Patrick Bailey, enabling them to explore their exam set works performed live. Early years centres in Budehaven, Tintagel, Camelford and Bodmin saw 1- 4 year olds take part in fun-filled sessions with BSO Associate – Hugh Nankivell, where they enjoyed creative music-making, exploring sounds and instruments as well as singing together. Primary schools; Fourlanesend School, Torpoint, Burraton Community Primary School, Saltash, Trenode CE VA School, Looe and Menheniot Primary School, Liskeard all adopted a musician for a day. -

Cognition and Learning Schools List

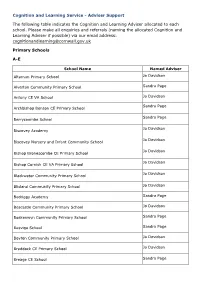

Cognition and Learning Service - Adviser Support The following table indicates the Cognition and Learning Adviser allocated to each school. Please make all enquiries and referrals (naming the allocated Cognition and Learning Adviser if possible) via our email address: [email protected] Primary Schools A-E School Name Named Adviser Jo Davidson Altarnun Primary School Sandra Page Alverton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Antony CE VA School Sandra Page Archbishop Benson CE Primary School Sandra Page Berrycoombe School Jo Davidson Biscovey Academy Jo Davidson Biscovey Nursery and Infant Community School Jo Davidson Bishop Bronescombe CE Primary School Jo Davidson Bishop Cornish CE VA Primary School Jo Davidson Blackwater Community Primary School Jo Davidson Blisland Community Primary School Sandra Page Bodriggy Academy Jo Davidson Boscastle Community Primary School Sandra Page Boskenwyn Community Primary School Sandra Page Bosvigo School Boyton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Jo Davidson Braddock CE Primary School Sandra Page Breage CE School School Name Named Adviser Jo Davidson Brunel Primary and Nursery Academy Jo Davidson Bude Infant School Jo Davidson Bude Junior School Jo Davidson Bugle School Jo Davidson Burraton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Callington Primary School Jo Davidson Calstock Community Primary School Jo Davidson Camelford Primary School Jo Davidson Carbeile Junior School Jo Davidson Carclaze Community Primary School Sandra Page Cardinham School Sandra Page Chacewater Community Primary -

STATISTICS for MISSION: Church Groups and Outreach/Community Engagement Activities 2013 District: 12 Cornwall District Circuit: 1 Camborne-Redruth

STATISTICS FOR MISSION: Church Groups and Outreach/Community Engagement Activities 2013 District: 12 Cornwall District Circuit: 1 Camborne-Redruth FX of Led by Years Shared Local Lay Volun- Employ- Pres- Deacon Group Type Group Name (Nos) Running Frequency Initiative Location Church Worship Preacher Officer teer ee byter Circuit Summary 52 2 0 2 3 42 3 1 0 Barripper Church Groups Creative Arts PBK Ladies Group 12 Monthly Ecumenical Church l Premises Community Outreach Activities/Engagement Projects Family Support Foodbank 3 Weekly or More Ecumenical Church Premises Beacon Church Groups Youth/Children - Other () Stay & Play 2 Weekly or More - Church l l Premises Youth/Children - Other () Holiday Club 3 Quarterly - Church l l Premises Mother and Baby/Toddler Praise & Play 2 Monthly - Church l l l Premises Arts & Crafts Flower Club 4 Monthly - Church l Premises Fellowship Group Fellowship 3 Monthly - Church l Premises Fellowship Group Ladies Fellowship 51 Fortnightly - Church l Premises Other () Soup & Sweet 3 Monthly - Church l Premises Other () Homebake 25 Monthly - Church l Premises Community Outreach Activities/Engagement Projects Playgroups/nurseries/pre- Toy Library 3 Weekly or More Ecumenical Church schools Premises Family Support Foodbank 3 Weekly or More Ecumenical Church l Premises Adult fellowship/social Camborne/Redruth 3 Fortnightly Local Authority Communit groups Disabled Club y Space Brea Church Groups - STATISTICS FOR MISSION: Church Groups and Outreach/Community Engagement Activities 2013 District: 12 Cornwall District Circuit: -

Cornwall Council Altarnun Parish Council

CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Baker-Pannell Lisa Olwen Sun Briar Treween Altarnun Launceston PL15 7RD Bloomfield Chris Ipc Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SA Branch Debra Ann 3 Penpont View Fivelanes Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY Dowler Craig Nicholas Rivendale Altarnun Launceston PL15 7SA Hoskin Tom The Bungalow Trewint Marsh Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TF Jasper Ronald Neil Kernyk Park Car Mechanic Tredaule Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RW KATE KENNALLY Dated: Wednesday, 05 April, 2017 RETURNING OFFICER Printed and Published by the RETURNING OFFICER, CORNWALL COUNCIL, COUNCIL OFFICES, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Kendall Jason John Harrowbridge Hill Farm Commonmoor Liskeard PL14 6SD May Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Five Lanes Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY McCallum Marion St Nonna's View St Nonna's Close Altarnun PL15 7RT Richards Catherine Mary Penpont House Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SJ Smith Wes Laskeys Caravan Farmer Trewint Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TG The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. -

Mondays to Fridays Saturdays Sundays Mondays

71 Derriford Hospital - Whitleigh - Saltash - Polbathic - Menheniot - Liskeard Transport for Cornwall Timetable valid from 31/05/2020 until further notice. Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service Restrictions Sch SH SH Sch Sch Derriford, Derriford Hospital (Stand 3) 0630 0710 0725 0835 1035 1135 1235 1335 1435 1435 1535 1645 1750 1855 2005 Whitleigh, Bodmin Road West (W-bound) 0639 0719 0734 0844 1044 1144 1244 1344 1444 1444 1544 1654 1759 1904 2014 Saltash, Fore Street Bottom (W-bound) 0734 0749 0859 1059 1259 1459 1459 1709 2029 Wearde, Broad Walk (W-bound) 1510 1510 Burraton, The Ploughboy (W-bound) 0740 0755 0905 1105 1305 1505 1515 1515 1715 2035 Burraton, Gilston Road Junction (S-bound) 0652 1157 1357 1557 1812 1917 Burraton, The Ploughboy (E-bound) 0655 1200 1400 1600 1815 1920 Landrake, Foot Bridge (W-bound) 0745 0910 1110 1310 1510 1520 1520 1720 Tideford, Quay Road (W-bound) 0748 0913 1113 1313 1513 1523 1523 1723 Trerulefoot, Polmarkyn Farm (SW-bound) 1527 Trerulefoot, Kernow Mill (SE-bound) 0751 St Germans, Elliot Hall (SE-bound) 0917 1117 1317 1517 1532 1727 St Germans, Rail Station (W-bound) 0918 1118 1318 1518 1533 1728 Polbathic, West Park (W-bound) 0919 1119 1319 1519 1534 1729 Trerulefoot, opp Kernow Mill 0923 1123 1323 1523 1538 1733 Bethany, opp Methodist Church 0927 1127 1327 1527 1542 1737 Doddycross, Shelter (NW-bound) 0932 1132 1332 1532 1547 1742 Menheniot, Church (N-bound) 0835 0937 1137 1337 1537 1552 -

CORNWALL Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph CORNWALL Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No Parish Location Position CW_BFST16 SS 26245 16619 A39 MORWENSTOW Woolley, just S of Bradworthy turn low down on verge between two turns of staggered crossroads CW_BFST17 SS 25545 15308 A39 MORWENSTOW Crimp just S of staggered crossroads, against a low Cornish hedge CW_BFST18 SS 25687 13762 A39 KILKHAMPTON N of Stursdon Cross set back against Cornish hedge CW_BFST19 SS 26016 12222 A39 KILKHAMPTON Taylors Cross, N of Kilkhampton in lay-by in front of bungalow CW_BFST20 SS 25072 10944 A39 KILKHAMPTON just S of 30mph sign in bank, in front of modern house CW_BFST21 SS 24287 09609 A39 KILKHAMPTON Barnacott, lay-by (the old road) leaning to left at 45 degrees CW_BFST22 SS 23641 08203 UC road STRATTON Bush, cutting on old road over Hunthill set into bank on climb CW_BLBM02 SX 10301 70462 A30 CARDINHAM Cardinham Downs, Blisland jct, eastbound carriageway on the verge CW_BMBL02 SX 09143 69785 UC road HELLAND Racecourse Downs, S of Norton Cottage drive on opp side on bank CW_BMBL03 SX 08838 71505 UC road HELLAND Coldrenick, on bank in front of ditch difficult to read, no paint CW_BMBL04 SX 08963 72960 UC road BLISLAND opp. Tresarrett hamlet sign against bank. Covered in ivy (2003) CW_BMCM03 SX 04657 70474 B3266 EGLOSHAYLE 100m N of Higher Lodge on bend, in bank CW_BMCM04 SX 05520 71655 B3266 ST MABYN Hellandbridge turning on the verge by sign CW_BMCM06 SX 06595 74538 B3266 ST TUDY 210 m SW of Bravery on the verge CW_BMCM06b SX 06478 74707 UC road ST TUDY Tresquare, 220m W of Bravery, on climb, S of bend and T junction on the verge CW_BMCM07 SX 0727 7592 B3266 ST TUDY on crossroads near Tregooden; 400m NE of Tregooden opp. -

RICHARD W. BARSTOW 26, Tregeseal, St. Just, Near Penzance, Cornwall, England

RICHARD W. BARSTOW 26, Tregeseal, st. Just, Near Penzance, Cornwall, England. ORDERING INFOhMATION Mail orders are promptly filled and despatched on a 7-day examination basis, subject to approval. Immediate refund guaranteed on return of specimens. Please quote the name and the number of the specimen(s) required, and enclose .O./Cheque with order. No charge is made fo~ postage and packing, except for over seas customers and postage over 50p. We reserve the right to make slight substitutions, if necessary, unless advised to the contrary. Special requests and 'wants lists' are welcome. We hope that we may be of some service to you, and assure you of our best attontion at all times. APRIL 1974 1. NATIVE ARSENIC. Burraton Combe Quarry, St. Stephens-by- Saltaoh, Cornwall. Specimen A- Superb, pure, metallic grey irregular shaped mass, with some conchoidal surfaces and odd encrustations of whitish AhSENOLITE. 4x2x2". £10; Specimen B- As specimen A- with much whitish Arsenolite; l~xl". £1. 50; Specimen C As Specimen B- lx'l". £1. 2. ATACAMITE. Broken Hill, New South Wales, Australia. Very rich, cellular mass of bright emerald green crystal aggregates with minor Limonite and fragments of Quartz. 3x3x2~". £12. 3. AURICK~LCITE. Char Kounhi Mine, Iran. Rich, lustrous, turquoise blue crystals scattered over and thickly aggregated in cavities in cellular Limonite. 3x2". £3. 4. BATHITE. Mina Ojuela, Mapimi, Durango, Mexico. Apple green, small, well formed crystals thickly scattered over gossan matrix with minor whitish Calcite in association. Specimen A- 2~x2"xl~". £3; Specimen B- Hx1~xl".:f2; Specimen C- l~xl" - without Calcite - 50p. -

Cornwall District Circuit: 1 Camborne, Redruth and Hayle

Statistical information on Church/Circuit/District membership, attendance and associated data relates to the current Conference- STATISTICS FOR MISSION approved Circuit/District structure. More information can be found at www.methodist.org.uk Church Groups and Outreach/Community Engagement Activities 2017 District: 12 Cornwall District Circuit: 1 Camborne, Redruth and Hayle Intended for (Church Attendees) Group Type Group Name Location Frequency Regular Irregular Non Att. Past Att. Total Att. Circuit Summary Total number of groups in the Circuit 71 1368 Angarrack Church Groups Crafts, Hobbies or Creative Arts Coffee Morning Church Premises Weekly or More l l l 20 Barripper Church Groups Crafts, Hobbies or Creative Arts PBK Ladies Group Church Premises Monthly l 24 Beacon Church Groups Church Groups for Young People () Stay & Play Church Premises Weekly or More l l l 22 Church Groups for Young People () Canjee Youth Group Church Premises Monthly l l l 6 Fellowship Group Fellowship Church Premises Monthly l 11 After School Club Open the Book School Fortnightly l l l l 100 Crafts, Hobbies or Creative Arts Craft Club Church Premises Fortnightly l l l 8 Crafts, Hobbies or Creative Arts Flower Club Church Premises Monthly l l l 6 Fellowship Group Soup & Sweet Church Premises Monthly l l l 40 Fellowship Group Homebake Church Premises Monthly l l l l 20 Carer and Toddler or Play Group Praise & Play Church Premises Monthly l l l 22 Crafts, Hobbies or Creative Arts CAMEO ladies group Church Premises Monthly l l l l 10 Bridge Church Groups Church Groups and Outreach/Community Engagement Activities 2017 District: 12 Cornwall District Circuit: 1 Camborne, Redruth and Hayle Intended for (Church Attendees) Group Type Group Name Location Frequency Regular Irregular Non Att. -

Allocation of Schools Per Case Work Officer

Information Classification: PUBLIC Statutory Special Educational Needs | Find Your Case Work Officer This list details the schools and postcodes that each case work officer is responsible for. West Cornwall Rupert Lawler: Area Casework Officer (West) email: [email protected] CWO: Bridget Bingley email: [email protected] Area Postcodes TR17, TR18, TR20 Early years Allocated by home address Independent special school (ISP) / out of Allocated by home address county Post 16 Allocated by home address Special school Curnow (Upper Y7 – 11) Allocated by home address, or if dual registered ACE Academy allocated by mainstream school base EHE Allocated by home address Allocated by home address if single registered and by APAs mainstream school base if dual registered Secondary schools Primary schools Humphry Davy Alverton, Germoe, Gulval, Heamoor, Ludgvan, Marazion, Mousehole, Newlyn, Pensans, St Hilary, St Mounts Bay Academy Maddern’s, St Mary’s CE, St Mary’s RC, Trythall CWO: Jenni Trewhella email: [email protected] Area Postcodes TR12, TR13 Early years Allocated by home address Independent special school (ISP) / out of Allocated by home address county Post 16 Allocated by home address Information Classification: PUBLIC Special school Curnow (Lower Y-1 – 6 & Post 16 Y12-14) Allocated by home address or if dual registered ACE Academy allocated by mainstream school base EHE Allocated by home address Allocated by home address if single registered and by APAs mainstream school base if dual registered Secondary -

Looking Back by John Pearn 2018 - 2019

Looking Back by John Pearn 2018 - 2019 The China Clay District by John Pearn 2018 - 2019 The last area of Cornwall to be re-organised to secondary education St.Dennis CP School 1951 to 1962 and St.Stephen in Brannel Secondary School September 1962 to December 1964 A period of 13 years Article prepared exclusively for the St.Dennis Village Website By Studio9KC Copyright C 2019 John Pearn Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Photo - St.Dennis C.P. School Outing ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Photo - Main Entrance St.Dennis C.P. School - 1957 ................................................................................................................. 3 Photo - St.Dennis C.P. School Staff - 1957 ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Photo - Mr.Jack Solomon ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Looking back at St. Dennis C.P. School 1957 to 1962 .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................