Flood Control Project Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Chapter 85

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 85.011 CHAPTER 85 DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION STATE PARKS, RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES 85.06 SCHOOLHOUSES IN CERTAIN STATE PARKS. 85.011 CONFIRMATION OF CREATION AND 85.20 VIOLATIONS OF RULES; LITTERING; PENALTIES. ESTABLISHMENT OF STATE PARKS, STATE 85.205 RECEPTACLES FOR RECYCLING. RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES. 85.21 STATE OPERATION OF PARK, MONUMENT, 85.0115 NOTICE OF ADDITIONS AND DELETIONS. RECREATION AREA AND WAYSIDE FACILITIES; 85.012 STATE PARKS. LICENSE NOT REQUIRED. 85.013 STATE RECREATION AREAS AND WAYSIDES. 85.22 STATE PARKS WORKING CAPITAL ACCOUNT. 85.014 PRIOR LAWS NOT ALTERED; REVISOR'S DUTIES. 85.23 COOPERATIVE LEASES OF AGRICULTURAL 85.0145 ACQUIRING LAND FOR FACILITIES. LANDS. 85.0146 CUYUNA COUNTRY STATE RECREATION AREA; 85.32 STATE WATER TRAILS. CITIZENS ADVISORY COUNCIL. 85.33 ST. CROIX WILD RIVER AREA; LIMITATIONS ON STATE TRAILS POWER BOATING. 85.015 STATE TRAILS. 85.34 FORT SNELLING LEASE. 85.0155 LAKE SUPERIOR WATER TRAIL. TRAIL PASSES 85.0156 MISSISSIPPI WHITEWATER TRAIL. 85.40 DEFINITIONS. 85.016 BICYCLE TRAIL PROGRAM. 85.41 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI PASSES. 85.017 TRAIL REGISTRY. 85.42 USER FEE; VALIDITY. 85.018 TRAIL USE; VEHICLES REGULATED, RESTRICTED. 85.43 DISPOSITION OF RECEIPTS; PURPOSE. ADMINISTRATION 85.44 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI TRAIL GRANT-IN-AID 85.019 LOCAL RECREATION GRANTS. PROGRAM. 85.021 ACQUIRING LAND; MINNESOTA VALLEY TRAIL. 85.45 PENALTIES. 85.04 ENFORCEMENT DIVISION EMPLOYEES. 85.46 HORSE -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Section 138.662

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 138.662 138.662 HISTORIC SITES. Subdivision 1. Named. Historic sites established and confirmed as historic sites together with the counties in which they are situated are listed in this section and shall be named as indicated in this section. Subd. 2. Alexander Ramsey House. Alexander Ramsey House; Ramsey County. History: 1965 c 779 s 3; 1967 c 54 s 4; 1971 c 362 s 1; 1973 c 316 s 4; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 3. Birch Coulee Battlefield. Birch Coulee Battlefield; Renville County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1973 c 316 s 9; 1976 c 106 s 2,4; 1984 c 654 art 2 s 112; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 4. [Repealed, 2014 c 174 s 8] Subd. 5. [Repealed, 1996 c 452 s 40] Subd. 6. Camp Coldwater. Camp Coldwater; Hennepin County. History: 1965 c 779 s 7; 1973 c 225 s 1,2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 7. Charles A. Lindbergh House. Charles A. Lindbergh House; Morrison County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1969 c 956 s 1; 1971 c 688 s 2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 8. Folsom House. Folsom House; Chisago County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 9. Forest History Center. Forest History Center; Itasca County. History: 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 10. Fort Renville. Fort Renville; Chippewa County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1973 c 225 s 3; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. -

The Campground Host Volunteer Program

CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM THE CAMPGROUND HOST VOLUNTEER PROGRAM MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 1 CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION Introduction This packet is designed to give you the information necessary to apply for a campground host position. Applications will be accepted all year but must be received at least 30 days in advance of the time you wish to serve as a host. Please send completed applications to the park manager for the park or forest campground in which you are interested. Addresses are listed at the back of this brochure. General questions and inquiries may be directed to: Campground Host Coordinator DNR-Parks and Recreation 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4039 651-259-5607 [email protected] Principal Duties and Responsibilities During the period from May to October, the volunteer serves as a "live in" host at a state park or state forest campground for at least a four-week period. The primary responsibility is to assist campers by answering questions and explaining campground rules in a cheerful and helpful manner. Campground Host volunteers should be familiar with state park and forest campground rules and should become familiar with local points of interest and the location where local services can be obtained. Volunteers perform light maintenance work around the campground such as litter pickup, sweeping, stocking supplies in toilet buildings and making emergency minor repairs when possible. Campground Host volunteers may be requested to assist in the naturalist program by posting and distributing schedules, publicizing programs or helping with programs. Volunteers will set an example by being model campers, practicing good housekeeping at all times in and around the host site, and by observing all rules. -

Minnesota State Parks.Pdf

Table of Contents 1. Afton State Park 4 2. Banning State Park 6 3. Bear Head Lake State Park 8 4. Beaver Creek Valley State Park 10 5. Big Bog State Park 12 6. Big Stone Lake State Park 14 7. Blue Mounds State Park 16 8. Buffalo River State Park 18 9. Camden State Park 20 10. Carley State Park 22 11. Cascade River State Park 24 12. Charles A. Lindbergh State Park 26 13. Crow Wing State Park 28 14. Cuyuna Country State Park 30 15. Father Hennepin State Park 32 16. Flandrau State Park 34 17. Forestville/Mystery Cave State Park 36 18. Fort Ridgely State Park 38 19. Fort Snelling State Park 40 20. Franz Jevne State Park 42 21. Frontenac State Park 44 22. George H. Crosby Manitou State Park 46 23. Glacial Lakes State Park 48 24. Glendalough State Park 50 25. Gooseberry Falls State Park 52 26. Grand Portage State Park 54 27. Great River Bluffs State Park 56 28. Hayes Lake State Park 58 29. Hill Annex Mine State Park 60 30. Interstate State Park 62 31. Itasca State Park 64 32. Jay Cooke State Park 66 33. John A. Latsch State Park 68 34. Judge C.R. Magney State Park 70 1 35. Kilen Woods State Park 72 36. Lac qui Parle State Park 74 37. Lake Bemidji State Park 76 38. Lake Bronson State Park 78 39. Lake Carlos State Park 80 40. Lake Louise State Park 82 41. Lake Maria State Park 84 42. Lake Shetek State Park 86 43. -

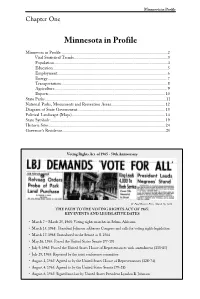

Minnesota in Profile

Minnesota in Profile Chapter One Minnesota in Profile Minnesota in Profile ....................................................................................................2 Vital Statistical Trends ........................................................................................3 Population ...........................................................................................................4 Education ............................................................................................................5 Employment ........................................................................................................6 Energy .................................................................................................................7 Transportation ....................................................................................................8 Agriculture ..........................................................................................................9 Exports ..............................................................................................................10 State Parks...................................................................................................................11 National Parks, Monuments and Recreation Areas ...................................................12 Diagram of State Government ...................................................................................13 Political Landscape (Maps) ........................................................................................14 -

Campground Host Program

Campground Host Program MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF PARKS AND TRAILS Updated November 2010 Campground Host Program Introduction This packet is designed to give you the information necessary to apply for a campground host position. Applications will be accepted all year but must be received at least 30 days in advance of the time you wish to serve as a host. Please send completed applications to the park manager for the park or forest campground in which you are interested. You may email your completed application to [email protected] who will forward it to your first choice park. General questions and inquiries may be directed to: Campground Host Coordinator DNR-Parks and Trails 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4039 Email: [email protected] 651-259-5607 Principal Duties and Responsibilities During the period from May to October, the volunteer serves as a "live in" host at a state park or state forest campground for at least a four-week period. The primary responsibility is to assist campers by answering questions and explaining campground rules in a cheerful and helpful manner. Campground Host volunteers should be familiar with state park and forest campground rules and should become familiar with local points of interest and the location where local services can be obtained. Volunteers perform light maintenance work around the campground such as litter pickup, sweeping, stocking supplies in toilet buildings and making emergency minor repairs when possible. Campground Host volunteers may be requested to assist in the naturalist program by posting and distributing schedules, publicizing programs or helping with programs. -

Interpretation Plan

8 Interpretation Plan Introduction This section of the corridor management plan provides guidance and direction for interpretive activities along the 287-mile long Byway. An important aspect of this byway’s interpretive strategy is to mesh resource management, product development and marketing within the interpretive effort. Each aspect of the byway’s efforts in each of these four categories should augment and support the other byway development categories. Status of Interpretation along the Byway There are existing interpretive strategies along the byway that are distinctive and unique that should be noted. These communities What Is Interpretation? There are many definitions for and/or sites have initiated personal services interpretation, offer interpretation. Credited as being services that provide unique access to resources, or offer the “Father of Interpre-tation”, distinctive products or services. These are just a few examples of Freeman Tilden stated in his book, interpretive initiatives that should be used as models for Interpreting Our Heritage, that considering other distinctive interpretive strategies. “Interpretation is an educational activity which aims to reveal Browns Valley to Ortonville meanings and relationships through the use of original objects, by • The Eahtonka II, Judy Drewicke. Charter cruises, public firsthand experience, and by excursions, step-on guide services illustrative media, rather than simply • Stony Run Trade Co., Don “Baboo” Felton. Paddle maker and to communicate factual information.” historian, lectures, displays, demonstrations and voyager Freeman Tilden, Interpreting Our goods. Heritage, 1962. • Independently Speaking, Brent Olson. Author, historian and storyteller. • Big Stone Lake State Park interpretive programs • Big Stone National Wildlife Refuge. Summer herd of bisons to Chapter 8 - Interpretive Plan 8-1 graze on refuge. -

Compliance with Legislative Authorization

Scenic Minnesota River valley American white pelicans MinnesotaMinnesota RiverRiver StateState TrailTrail MasterMaster PlanPlan Granite outcropping DRAFT Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Division of Trails Waterways June 2007 Upper Sioux Agency historic site Table of Contents Chapter 1: Executive Summary .......................................................................................................1 Chapter 2: Introduction...................................................................................................................5 Planning History .....................................................................................................................7 Goals and Objectives of the Planning Process......................................................................10 Planning Process ...................................................................................................................12 Compliance with Legislative Authorization .........................................................................13 Vision Statement and Goals..................................................................................................18 Chapter 3: Trail Uses ...................................................................................................................19 Chapter 4: Potential Trail Alignments ...........................................................................................23 Segment 1: Big Stone Lake State Park to Ortonville...........................................................25 -

Reviews & Short Features

REVIEWS OF BOOKS The Doctors Mayo. By HELEN CLAPESATTLE. (Minneapolis, The University of Minnesota Press, 1941. xiv, 822 p. Illus trations, maps. $3.75.) Miss Clapesattle opens her biography of the Doctors Mayo by calling attention to the " paradox of Rochester." This paradox, she beheves, lies In the fact that a " little town on the edge of nowhere'' Is " one of the world's greatest medical centers." The challenge that faced the author was to explain the paradox. It was a big challenge and meant more than writing the saga of three extraordinary men. It meant placing those men, whose lives spanned more than a century. In a setting of extraordinary sweep. For neither the paradox nor the men could be explained in any single frame of reference. Obviously, she had to understand and to make clear to her readers the changing character of medical science and practice from the 1840's, when young William Worrall Mayo migrated to America, to 1939, when William James and Charles Horace Mayo died. She had to explore the customs and assumptions of at least three genera tions of Americans, study the transition of the Middle West from pioneer to modern times, appraise a changing civilization as mani fested in an American local community, view the emergence and growth of a great institution projected from the lives of individual men, and see clearly not only her major characters but also the many figures associated with them. All this meant a prodigious amount of research, combing old newspapers, reading medical journals, interview ing many men and women, studying manuscripts and case histories, following clues wherever they led, assembling material from a bewilder ing variety of sources, and organizing it Into a narrative, not bewild ering, but clear and compact. -

Final Lac Qui Parle River Watershed Restoration and Protection Strategy

Watershed August 2021 Lac qui Parle River Watershed Restoration and Protection Strategy Report Authors Timothy Erickson, P.E., Houston Engineering, Inc. Scott Kronholm, PhD, Houston Engineering, Inc. Lori Han, PhD, Houston Engineering, Inc. Contributors/acknowledgements Katherine Pekarek-Scott, MPCA Scott MacLean, MPCA Marco Graziani, MPCA Anna Bosch, MPCA Kelli Nerem, MPCA Chuck Regan, MPCA Ian Ackman, MPCA Ryan Bjerke, DNR WRAPS Local Work Group Lac qui Parle – Yellow Bank Watershed District Yellow Medicine County SWCD Mitch Enderson Brooke Buysse Mark Hiles Trudy Hastad Kurt Johnson Jason Beckler Jared Roiland Anita Borg Darrel Ellefson Brayden Anderson Minnesota Department of Dave Craigmile Tyler Knutson Natural Resources David Ludvigson Jon Lore John Cornell Yellow Medicine County Ryan Bjerke Michael Frank Christopher Balfany Brady Swanson Jolene Johnson Brooke Hacker Lac qui Parle County Taralee Latozke Deron Brehmer Lincoln County SWCD Jenny Breberg Dale Sterzinger National Resources John Maatz Colleen Wichern Conservation Service Jacob Harrison Burton Hendrickson Lac qui Parle County SWCD Rhyan Schicker Board of Water and Soil U.S. Fish and Wildlife Quintin Peterson Resources Stephanie Bishir Chessa Frahm Douglas Goodrich Cover photo credit: Lac qui Parle River MPCA webpage https://www.pca.state.mn.us/water/watersheds/lac-qui-parle-river The MPCA is reducing printing and mailing costs by using the Internet to distribute reports and information to a wider audience. Visit our website for more information. The MPCA reports are printed on 100% post-consumer recycled content paper manufactured without chlorine or chlorine derivatives. Those with disabilities limiting their ability to access report information may contact the MPCA Watershed Project Manager to provide alternate formats that suit their needs. -

Preserving and Interpreting Minnesota's Historic Sites

JEAN Baptiste Faribault House at Mendota PRESERVING and INTERPRETING Minnesota's HISTORIC SITES RUSSELL W. FRIDLEY AN ORGANIZED MOVEMENT to pre state is changing. Modernization of cities serve Minnesota's major historic sites has and towns, population expansion into sub gained considerable mornentum in recent urbs and rural areas, industrial growth, mili years. While a relatively small number of tary installations, and huge state and federal people are involved in this effort, and their highway programs are exerting tremendous work seldom receives public attention, they pressure on once neglected or scarcely no are pervaded by a sense of the deepest ur ticed historic sites. If steps are not rapidly gency. They are aware that a period of crisis taken to preserve these places where Min is at hand in the struggle to save the signifi nesota history was made, they will soon be cant physical remnants of our past. More lost forever. than is generally realized, the face of our Though few in number and armed with all too meager resources, those engaged in MR. FRmLEY, who is the director of the society, has based this article on talks given before the the battle to conserve Minnesota's historic Great Lakes Conference on Historic Sites, held spots are united by a keen awareness of the at Mackinac Island State Park, and the National values at stake. Our society is changing Conference on State Parks, in Pacific Grove, more rapidly than ever before and our California, on August 7 and September 21,1959. bonds with the past are each day becoming 58 MINNESOTA History more tenuous. -

Dakota Portraits

DAKOTA PORTRAITS INTRODUCTION These "Dakota Portraits," written by the Reverend Stephen R. Riggs in 1858, were published in the Minnesota Free Press of St. Peter at irregular intervals from January 27 to July 14, 1858. The newspaper itself was a weekly, edited by William C. Dodge, and appeared for the first time on May 27, 1857. With the issue of November 17, 1858, its publication was, for financial reasons, temporarily suspended. In April of the fol lowing year, however, the paper resumed publication under the name of the St. Peter Free Press and it continued to be issued until December 21 of that year, when the plant was destroyed by fire.1 The last issue in the file of the Minnesota Historical Society is dated December 7, 1859. Because of his long residence among the Dakota Indians, Riggs was peculiarly well fitted to describe their characteristics. The sketches are written from his own personal knowledge, and present a number of persons who are scarcely known apart from his account of them. The author was a Presbyterian missionary to the Sioux. He was born in Ohio in 1812, a descendant of " a long line of godly men, ministers of the gos pel and others," and received a good education at Jefferson College and Western Theological Seminary, Allegheny, Penn sylvania. After he was licensed as a preacher, he was sent by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to aid Dr. Thomas S. Williamson in his work with the Indians of the Northwest. Riggs and his wife arrived at Fort Snelling to begin their labors in June, 1837, and spent the summer with the Reverend Jedediah Stevens at Lake Harriet.