Intraguild Relationships Between Sympatric Predators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks Part of the Far North & Far West Region (Region 13) Historical Research Pty Ltd Adelaide in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd Lyn Leader-Elliott Iris Iwanicki December 2002 Frontispiece Woolshed, Cordillo Downs Station (SHP:009) The Birdsville & Strzelecki Tracks Heritage Survey was financed by the South Australian Government (through the State Heritage Fund) and the Commonwealth of Australia (through the Australian Heritage Commission). It was carried out by heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd, in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd, Lyn Leader-Elliott and Iris Iwanicki between April 2001 and December 2002. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia and they do not accept responsibility for any advice or information in relation to this material. All recommendations are the opinions of the heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd (or their subconsultants) and may not necessarily be acted upon by the State Heritage Authority or the Australian Heritage Commission. Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes including for personal or educational uses. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires written permission from the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to either the Manager, Heritage Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001, or email [email protected], or the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601, or email [email protected]. -

Mailman of the Birdsville Track: the Story of Tom Kruse Free

FREE MAILMAN OF THE BIRDSVILLE TRACK: THE STORY OF TOM KRUSE PDF Kristin Weidenbach,Peter Hosking | none | 11 Mar 2013 | Bolinda Publishing | 9781743156735 | English | Australia Tom Kruse the birdsville mailman Goodreads helps you keep track of Mailman of the Birdsville Track: The Story of Tom Kruse you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. The Birdsville Track is one of the best-known tracks in Australia, and for 20 years Tom Kruse was the mailman, battling searing heat, floods Mailman of the Birdsville Track: The Story of Tom Kruse mechanical breakdowns. He made the run every fortnight and was a lifeline to the isolated settlements and stations along the way, delivering everything from letters to essential supplies. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published by Hodder first published January More Details Original Title. Other Editions Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Mailman of the Birdsville Trackplease sign up. Be the first to ask a question about Mailman of the Birdsville Track. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Jan 22, Janelle marked it as dnf. I didn't get far into the first chapter. Maybe I'm too much of an impatient reader, but I was very bored. View all 3 comments. Jan 08, Dale rated it did not like it Shelves: abandoned. -

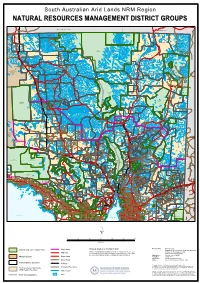

Natural Resources Management District Groups

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region NNAATTUURRAALL RREESSOOUURRCCEESS MMAANNAAGGEEMMEENNTT DDIISSTTRRIICCTT GGRROOUUPPSS NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Mount Dare H.S. CROWN POINT Pandie Pandie HS AYERS SIMPSON DESERT RANGE SOUTH Tieyon H.S. CONSERVATION PARK ALTON DOWNS TIEYON WITJIRA NATIONAL PARK PANDIE PANDIE CORDILLO DOWNS HAMILTON DEROSE HILL Hamilton H.S. SIMPSON DESERT KENMORE REGIONAL RESERVE Cordillo Downs HS PARK Lambina H.S. Mount Sarah H.S. MOUNT Granite Downs H.S. SARAH Indulkana LAMBINA Todmorden H.S. MACUMBA CLIFTON HILLS GRANITE DOWNS TODMORDEN COONGIE LAKES Marla NATIONAL PARK Mintabie EVERARD PARK Welbourn Hill H.S. WELBOURN HILL Marla - Oodnadatta INNAMINCKA ANANGU COWARIE REGIONAL PITJANTJATJARAKU Oodnadatta RESERVE ABORIGINAL LAND ALLANDALE Marree - Innamincka Wintinna HS WINTINNA KALAMURINA Innamincka ARCKARINGA Algebuckinna Arckaringa HS MUNGERANIE EVELYN Mungeranie HS DOWNS GIDGEALPA THE PEAKE Moomba Evelyn Downs HS Mount Barry HS MOUNT BARRY Mulka HS NILPINNA MULKA LAKE EYRE NATIONAL MOUNT WILLOUGHBY Nilpinna HS PARK MERTY MERTY Etadunna HS STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION ETADUNNA TALLARINGA PARK RESERVE CONSERVATION Mount Clarence HS PARK COOBER PEDY COMMONAGE William Creek BOLLARDS LAGOON Coober Pedy ANNA CREEK Dulkaninna HS MABEL CREEK DULKANINNA MOUNT CLARENCE Lindon HS Muloorina HS LINDON MULOORINA CLAYTON Curdimurka MURNPEOWIE INGOMAR FINNISS STUARTS CREEK SPRINGS MARREE ABORIGINAL Ingomar HS LAND CALLANNA Marree MUNDOWDNA LAKE CALLABONNA COMMONWEALTH HILL FOSSIL MCDOUAL RESERVE PEAK Mobella -

MARREE - INNAMINCKA Natural Resources Management Group

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region MARREE - INNAMINCKA Natural Resources Management Group NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND SIMPSON DESERT CONSERVATION PARK Pastoral Station ALTON DOWNS MULKA PANDIE PANDIE Boundary CORDILLO DOWNS Conservation and National Parks Regional reserve/ SIMPSON DESERT Pastoral Station REGIONAL RESERVE Aboriginal Land Marree - Innamincka CLIFTON HILLS NRM Group COONGIE LAKES NATIONAL PARK INNAMINCKA REGIONAL RESERVE SA Arid Lands NRM Region Boundary INNAMINCKA Dog Fence COWARIE Major Road MACUMBA ! KALAMURINA Innamincka Minor Road / Track MUNGERANIE Railway GIDGEALPA ! Moomba Cadastral Boundary THE PEAKE Watercourse LAKE EYRE (NORTH) LAKE EYRE MULKA Mainly Dry Lake NATIONAL PARK MERTY MERTY STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION RESERVE PARK ETADUNNA BOLLARDS ANNA CREEK LAGOON DULKANINNA MULOORINA LINDON LAKE BLANCHE LAKE EYRE (SOUTH) MULOORINA CLAYTON MURNPEOWIE Produced by: Resource Information, Department of Water, Curdimurka ! STRZELECKI Land and Biodiversity Conservation. REGIONAL Data source: Pastoral lease names and boundaries supplied by FINNISS MARREE RESERVE Pastoral Program, DWLBC. Cadastre and Reserves SPRINGS LAKE supplied by the Department for Environment and CALLANNA ABORIGINAL ! Marree CALLABONNA Heritage. Waterbodies, Roads and Place names LAND FOSSIL supplied by Geoscience Australia. STUARTS CREEK MUNDOWDNA Projection: MGA Zone 53. RESERVE Datum: Geocentric Datum of Australia, 1994. MOOLAWATANA MOUNT MOUNT LYNDHURST FREELING FARINA MULGARIA WITCHELINA UMBERATANA ARKAROOLA WALES SOUTH NEW -

Regional-Map-Outback-Qld-Ed-6-Back

Camooweal 160 km Burke and Wills Porcupine Gorge Charters New Victoria Bowen 138° Camooweal 139° 140° 141° Quarrells 142° 143° Marine fossil museum, Compton Downs 144° 145° 146° Charters 147° Burdekin Bowen Scottville 148° Roadhouse 156km Harrogate NP 18 km Towers Towers Downs 80 km 1 80 km 2 3 West 4 5 6 Kronosaurus Korner, and 7 8 WHITE MTNS Warrigal 9 Milray 10 Falls Dam 11 George Fisher Mine 139 OVERLANDERS 48 Nelia 110 km 52 km Harvest Cranbourne 30 Leichhardt 14 18 4 149 recreational lake. 54 Warrigal Cape Mt Raglan Collinsville Lake 30 21 Nonda Home Kaampa 18 Torver 62 Glendower NAT PARK 14 Biralee INDEX OF OUTBACK TOWNS AND Moondarra Mary Maxwelton 32 Alston Vale Valley C Corea Mt Malakoff Mt Bellevue Glendon Heidelberg CLONCURRY OORINDI Julia Creek 57 Gemoka RICHMOND Birralee 16 Tom’s Mt Kathleen Copper and Gold 9 16 50 Oorindi Gilliat FLINDERS A 6 Gypsum HWY Lauderdale 81 Plains LOCALITIES WITH FACILITIES 11 18 9THE Undha Bookin Tibarri 20 Rokeby 29 Blantyre Torrens Creek Victoria Downs BARKLY 28 Gem Site 55 44 Marathon Dunluce Burra Lornsleigh River Gem Site JULIA Bodell 9 Alick HWY Boree 30 44 A 6 MOUNT ISA BARKLY HWY Oonoomurra Pymurra 49 WAY 23 27 HUGHENDEN 89 THE OVERLANDERS WAY Pajingo 19 Mt McConnell TENNIAL River Creek A 2 Dolomite 35 32 Eurunga Marimo Arrolla Moselle 115 66 43 FLINDERS NAT TRAIL Section 3 Outback @ Isa Explorers’ Park interprets the World Rose 2 Torrens 31 Mt Michael Mica Creek Malvie Downs 52 O'Connell Warreah 20 Lake Moocha Lake Ukalunda Mt Ely A Historic Cloncurry Shire Hall, 25 Rupert Heritage listed Riversleigh Fossil Field and has underground mine tours. -

Outback South Australia & Flinders

A B C Alice Springs D E F G H J K Kulgera QAA Big Red Surveyor NORTHERN TERRITORY NORTHERN TERRITORY LINE Generals Poeppel Corner SOUTH AUSTRALIA LINE Birdsville QUEENSLAND Haddon Corner Major Road Sealed K1 Corner SOUTH AUSTRALIA Mount Dare Hotel SOUTH AUSTRALIA Witjira National Park FRENCH Major Road Unsealed RIG Simpson Desert Mt Woodroffe Dalhousie Conservation Park 1 Springs YANDRUWANDHA 1 Secondary Road Sealed RIG / YAWARRAWARRKA RD RD Secondary Road Unsealed LINE Aparawatatja Strzelecki Community Alberga Goyder 'Cordillo Downs' Other Road Unsealed Fregon WANGKANGURRU / YARLULANDI Lagoon Desert Simpson Desert 'Arrabury' 4WD Only Simpson Desert River Macumba Innamincka Station ANANGU Regional Reserve Regional PITJANTJATJARA Warburton Marla OODNADATTA Reserve YANKUNYTJATJARA Mintabie Crossing Coongie Lakes Explorer’s Way STUART River National Park WESTERN ABORIGINAL Ck Sturt LAND A87 Route Marker Oodnadatta Ck 2 ANTAKIRIJA 2 Stony Walkers Crossing Visitor Information Centre ANANGU PITJANTJATJARA RD 'Kalamurina' RD River Warburton Innamincka YANKUNYTJATJARA Cadney DESERT Desert Aboriginal Cultural Experience PAINTED Homestead TRACK 'Copper Accommodation Hills' KEMPE Mungerannie (Indicated for Outback and Neales Hotel Moomba Flinders Ranges region only) Lake Eyre (No Public SOUTH Great Victoria Desert Tirari Services) Mamungari Con. Park Lake Eyre Cooper Annes Corner Defence North National Park Desert Centre A87 ANNE Tallaringa Elliot TRACK Strzelecki Vokes Hill Woomera Conservation Corner MARALINGA Price Strzelecki Park William QUEENSLAND TJARUTJA THE Con. Lake 3 Creek Regional Desert SOUTH AUSTRALIA 3 ABORIGINAL BEADELL Gregory HWY Park DIERI Reserve LAND Coober Pedy RD See Dog Fence WILLIAM CREEK PASTORAL PROPERTIES Lake Eyre South Outback Cameron The roads in this region pass through working ARABUNNA TRACK 'Muloorina' BIRDSVILLE Corner pastoral properties. -

05Ewortliy AGRIC(1LTLIRAL COLLEGE

I 05EWORTliY AGRIC(1LTLIRAL COLLEGE. PRESENT STU DENTS. THIRIJ YEAR. L. j. Cook \ 1. O. \\ este G. E. Wells r. Rumhall .'. R. Stt.ngstt!T T R. ).lolen G \V. Linm:u SECOND Yi-:AP. :-J. S. i Olhcringham S. R. Dyer S. :C. Gender50 M. Urucl.! C. r" nlln~tonc H. Leake l. S. Voung F ..\. Wlwaton l\L lIunter R. )1. Wri)!, il~ W. 1. E Everard F. C. M c Lau~hlin T . R. \\\.:lbollrn I;: . \\'. !=:andland G.v- lIali .... H . gdwdTlis M. G. ~t~\IIIar t J. C. Trumllie It R. J:llIl es B. J. \lagarey H. L. J\lallud C, C . .\lasson C. C. I', (;oddar~1 :\. P. Stone I'IRST YEAR. S. II. T. Besl l" L. Pbillil'" )0', Ft'lslead E.]. Stanley Low I. H . FIt ~tcht! r F. H. ::::nook ~\. L. T . l"ry H. Soll y R. Hill 11. Snow , U Hoil!;! K.. W. Tamblyn ( ;, h'es R. I). Tlllley G. E. Love J.. t. Wilkin,,>on H. ::i. ro. Nenleheck SPECl" L V & 0, .\ . SHall " El (olltlabulI1 gladio! suos III I)onu!:r~s ~I l'ln«(,I$ suas 111 talc-it$. " flgriclJItlJral CoII~ge, ~OSEWORTHY, 80-0 'rR A UST..RALIA . .I/l1!jijl~l·f!Jr .tI!l,·i/:IIUlo·e: 'fill: ]ION. K II COOMD":, ill. I'. itbe $taff. P .. j"li~i}luJ. aRd l.Qf""1" 011 A!j.-ir«It",· PROF. .A. J. PERK I;.;R HQ ........ ',prv.f'r, twrl LI!("I""(;" 0/1 Nllyli~h aHd Bvok.'-upnJg: ~lr. D. MEKZlB. -

Download 1919 Expedition406.3 Kb

First medical relief expedition, 1919 In 1919 a group of pastoralists and the South travelled south along the Birdsville Track to Marree, Australian government provided £1000 for a medical where they caught a train back to Adelaide. inspection of the health of Aboriginal people in the During the expedition, horses and two buggies were state’s settled districts. Basedow was commissioned to used as transport, while a third buggy was acquired for undertake the work, with his wife Nell acting as nurse. crossing a difficult stretch of heavy sandhill country The first of these expeditions was to inspect the health after Murnpeowie station. Other than sandhills, of Aboriginal people in north-eastern South Australia and some adjacent areas of Queensland. Hired for this the terrain tended to be flat to undulating plains, expedition were Basedow’s older brother Erwin and lake pans and gibber country (desert terrain strewn Richard Grenfell Thomas, the 18-year-old son of one with stones). As much of the area was in drought of the pastoralists who helped finance the expedition. and bare of grass cover, dust storms were reasonably Erwin and Thomas both provided general assistance commonplace. On the leg between Innamincka and looked after the expedition horses and buggies. and Cordillo Downs station the expedition struck a particularly savage one, as Thomas noted in his diary The departure point was Farina, on the railway entry for 6 October: line south of Marree, where four days were spent organising supplies and horses. Leaving Farina on After lunch the wind & dust increased till a 13 August, the party travelled to Mount Lyndhurst furious gale was blowing & it was impossible station and along the Strzelecki Track to Innamincka, to see more than a few yards in front. -

Tracks of the Marree-Innamincka District

Birdsville Strzelecki Legendary tracks of the Marree-Innamincka District Created by the local Marree-Innamincka NRM Group . a R ‘Durrie’ QUEENSLAND tin an Big Red Diam Poeppel Corner Birdsville K1 ‘Pandie Pandie’ Haddon Cadelga Corner Outstation (Ruin) Strzelecki Simpson ‘Alton 422 K Downs’ AC Desert LINE TR E Goyder Desert Cordillo Downs ID S Lagoon (Historic Woolshed) N I Simpson Desert ‘Arrabury’ W CORDILLO RD Regional Reserve ‘Clifton alke r s Hills’ C r o s s i n g k Warburton P C Crossing A Coongie Lakes R n PAR Innamincka 0 N 100 o National Park rt 308 Regional bu Sturt km Reserve QUEENSLAND ar W Walkers Stony Burke And Wills ‘Cowarie’ Crossing K Dig Tree ‘Gidgealpa’ ‘Innamincka’ Nappa Merrie C A C Bridge R k T Desert Innamincka Strzelecki ‘Mungerannie’ Desert Tirari Mungerannie Kati Thanda- Moomba Hotel r Desert e (No public Lake Eyre p o access or o North C services) Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre ‘Mulka’ Lake K ‘Epsilon’ Mulka H.S. (Ruin) C k Lake A C National Park Hope R i Killalpaninna T k lec Bethesda e z Mission Ruins M.V. Tom tr Elliot S Brennan Mem. ‘Merty Merty’ Price 205 Strzelecki ‘Etadunna’ Con. Regional Park E L L Reserve I Lake ‘Bollards Cameron V ‘Dulkaninna’ S Gregory Strzelecki Lagoon’ Corner D I R K Crossing C BI E L E Sturt Nat. Kati Thanda- ‘Muloorina’ ‘Clayton’ Strzelecki ‘Lindon’ Z River Lake R Park Lake Eyre T Desert F S r Clayton o Blanche THE South m e Montecollina COBBLER O Blanchewater O Lake Harry Bore D N Homestead ADA H.S. -

Kowari Monitoring in Sturt's Stony Desert, South Australia

Kowari monitoring in Sturt’s Stony Desert, South Australia May 2018 Catherine Lynch & Robert Brandle 1 DISCLAIMER The South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board, and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of use of the information contained herein as to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board and its employees expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. This report may be cited as: South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board (2018). Kowari monitoring in Sturt’s Stony Desert SA. South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board, Port Augusta. Cover image: A Kowari on typical gibber pavement habitat. Photo by Nathan Beerkens (Arid Recovery). © South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board 2018 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Commonwealth), no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission obtained from the South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Regional Manager, South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board, Level 1 9 Mackay Street, PO Box 78, Port Augusta, SA, 5700. i Table of Contents Landholder Summary ........................................................................................................... -

Downloaded on 20 April 2011

Allen et al. Frontiers in Zoology 2014, 11:56 http://www.frontiersinzoology.com/content/11/1/56 RESEARCH Open Access Sympatric prey responses to lethal top-predator control: predator manipulation experiments Benjamin L Allen1,2*, Lee R Allen2, Richard M Engeman3 and Luke K-P Leung1 Abstract Introduction: Many prey species around the world are suffering declines due to a variety of interacting causes such as land use change, climate change, invasive species and novel disease. Recent studies on the ecological roles of top-predators have suggested that lethal top-predator control by humans (typically undertaken to protect livestock or managed game from predation) is an indirect additional cause of prey declines through trophic cascade effects. Such studies have prompted calls to prohibit lethal top-predator control with the expectation that doing so will result in widespread benefits for biodiversity at all trophic levels. However, applied experiments investigating in situ responses of prey populations to contemporary top-predator management practices are few and none have previously been conducted on the eclectic suite of native and exotic mammalian, reptilian, avian and amphibian predator and prey taxa we simultaneously assess. We conducted a series of landscape-scale, multi-year, manipulative experiments at nine sites spanning five ecosystem types across the Australian continental rangelands to investigate the responses of sympatric prey populations to contemporary poison-baiting programs intended to control top-predators (dingoes) for livestock protection. Results: Prey populations were almost always in similar or greater abundances in baited areas. Short-term prey responses to baiting were seldom apparent. Longer-term prey population trends fluctuated independently of baiting for every prey species at all sites, and divergence or convergence of prey population trends occurred rarely. -

Santos We Have the Energy

Santos We have the energy April 2016 South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board The effect of wild dog control on cattle production and biodiversity in the South Australian arid zone 1 Eldridge SR, Bird PL, Brook A, Campbell G, Miller HA, Read JL and Allen BL South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board Disclaimer The South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board, and Natural Resources SA Arid Land employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of use of the information contained herein as to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board and Natural Resources SA Arid Land employees expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. This report may be cited as: Eldridge S.R., Bird P.L., Campbell G., Miller H.A., Read J.L. and Allen B.L. (2016). The effect of wild dog control on cattle production and biodiversity in the arid zone of South Australia. For the purpose of this report, the term ‘wild dog’ refers to dingoes (Canis lupus dingo), domestic dogs that are wild-living (Canis lupus familiaris) and their hybrids. © South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board 2015 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Commonwealth), no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission obtained from the South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management