RT&H and R&PW As Percentage Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

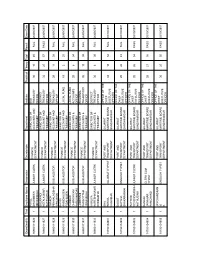

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN 98, MAULANA AZAD AND Andaman & ROAD, PORT BLAIR, NICOBAR Nicobar State 744101, ANDAMAN & 943428146 ISLAND ANDAMAN Coop Bank Ltd NICOBAR ISLAND PORT BLAIR HDFC0CANSCB 0 - 744656002 HDFC BANK LTD. 201, MAHATMA ANDAMAN GANDHI ROAD, AND JUNGLIGHAT, PORT NICOBAR BLAIR ANDAMAN & 98153 ISLAND ANDAMAN PORT BLAIR NICOBAR 744103 PORT BLAIR HDFC0001994 31111 ANDHRA HDFC BANK LTD6-2- 022- PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD 57,CINEMA ROAD ADILABAD HDFC0001621 61606161 SURVEY NO.109 5 PLOT NO. 506 28-3- 100 BELLAMPALLI ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH BELLAMPAL 99359 PRADESH ADILABAD BELLAMPALLI 504251 LI HDFC0002603 03333 NO. 6-108/5, OPP. VAGHESHWARA JUNIOR COLLEGE, BEAT BAZAR, ANDHRA LAXITTIPET ANDHRA LAKSHATHI 99494 PRADESH ADILABAD LAXITTIPET PRADESH 504215 PET HDFC0003036 93333 - 504240242 18-6-49, AMBEDKAR CHOWK, MUKHARAM PLAZA, NH-16, CHENNUR ROAD, MANCHERIAL - MANCHERIAL ANDHRA ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH MANCHERIY 98982 PRADESH ADILABAD PRADESH 504208 AL HDFC0000743 71111 NO.1-2-69/2, NH-7, OPPOSITE NIRMAL ANDHRA BUS DEPO, NIRMAL 98153 PRADESH ADILABAD NIRMAL PIN 504106 NIRMAL HDFC0002044 31111 #5-495,496,Gayatri Towers,Iqbal Ahmmad Ngr,New MRO Office- THE GAYATRI Opp ANDHRA CO-OP URBAN Strt,Vill&Mdl:Mancheri MANCHERIY 924894522 PRADESH ADILABAD BANK LTD al:Adilabad.A.P AL HDFC0CTGB05 2 - 504846202 ANDHRA Universal Coop Vysya Bank Road, MANCHERIY 738203026 PRADESH ADILABAD Urban Bank Ltd Mancherial-504208 AL HDFC0CUCUB9 1 - 504813202 11-129, SREE BALAJI ANANTHAPUR - RESIDENCY,SUBHAS -

Mission Readiness Mandate the Mandate of the Ministry of Defence Is Derived from Article 241:1 (A), (B) and (C) of the Constitution of the Kenya Defence Forces Act No

KENYA DEFENCE FORCES Majeshi YetuYetu VOLUME 17, 2020 Back to School 2021 New Dawn for Security Telecommunication Services Things to look out for in 2021; - Ulinzi Sports Complex - Space Science Advancement Mission Readiness Mandate The Mandate of the Ministry of Defence is derived from Article 241:1 (a), (b) and (c) of the Constitution of the Kenya Defence Forces Act No. 25 of 2012. Vision A premier, credible and mission capable force deeply rooted in professionalism. Mission To defend and protect the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic, assist and cooperate with other authorities in situations of emergency or disaster and restore peace in any part of Kenya affected by unrest or instability as assigned. Commitment The Ministry of Defence is committed to defending the people of the Republic of Kenya and their property against external aggression and also providing support to Civil Authority. Preamble The Ministry of Defence is comprised of the Kenya Army, the Kenya Air Force, the Kenya Navy, the Defence Force Constabulary and the Civilian Staff. Core Values To achieve its Mission and Vision, the Ministry is guided by its core values and beliefs namely: Apolitical: The Defence Forces will steer clear of politics and will remain steadfastly apolitical. The Civil Prerogative: The Defence Forces shall always subordinate itself to democratic Civil Authority and will treat the people of Kenya and its other clients with civility at all times. Loyalty and Commitment: The Defence Forces will uphold its loyalty and commitment to the Commander-in-Chief and the Kenya People of the Republic of Kenya through the chain of command. -

Saurashtra University Re – Accredited Grade ‘B’ by NAAC (CGPA 2.93)

Saurashtra University Re – Accredited Grade ‘B’ by NAAC (CGPA 2.93) Jadav, Rajan D., 2010, “Ecological Status and Importance of Grasslands (Vidis) in Conservation of Avian”, thesis PhD, Saurashtra University http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu/id/eprint/569 Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Saurashtra University Theses Service http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu [email protected] © The Author “ECOLOGICAL STATUS AND IMPORTANCE OF GRASSLANDS (VIDIS) IN CONSERVATION OF AVIAN FAUNA IN SAURASHTRA” Thesis submitted to Saurashtra University, Rajkot For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Zoology (Animal sciences) By Rajan. D. Jadav Department of Biosciences Saurashtra University Rajkot – 364002 April 2010 SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF BIOSCIENCE University Campus. RAJKOT-360005 (INDIA) Gujarat. CERTIFICATE Tel: (O) 0091-281-2586419 Fax: 0091-281-2586419 DATE: I have great pleasure in forwarding the thesis of Mr. Rajan. D. Jadav entitled “Ecological status and importance of grasslands (vidis) in conservation of avian fauna in Saurashtra.” for accepting the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Zoology (Animal sciences) from the Saurashtra University Rajkot. This Study was carried out by Mr. -

October 2007

ExamSeatNo Trial Employee Name Designation Secretariate Department Institute Practical Theory Total Result Exam Date PATEL DIRECTOR OF SUB FINANCE 69890111026 1 DHARMESH JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS AND TREASURY 30 15 45 FAIL 26/09/2007 DEPARTMENT ARVINDBHAI TREASURY OFFICE DALAWADI DIRECTOR OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890111027 1 HETALKUMAR JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNT AND TREASURY 32 25 57 PASS 26/09/2007 DEPARTMENT NATAVARLAL TREASURY OFFICE THAKOR DIRECTOR OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890111028 1 PRAHALADBHAI SUB AUDITOR ACCOUNT AND TREASURY 28 11 39 FAIL 26/09/2007 DEPARTMENT VIRAJBHAI TREASURY OFFICE DAVDI DIRECTOR OF FINANCE 69890111029 1 AABIDHUSEN SUB AUDITOR ACCOUNT AND LOCAL FUND 18 2 20 FAIL 26/09/2007 DEPARTMENT FIDAHUSEN TREASURY PARMAR DIRECTOR OF LOCAL FUND FINANCE 69890111030 1 GHANSHYAM SUB AUDITOR ACCOUNTS & ACCOUNTS 28 6 34 FAIL 26/09/2007 DEPARTMENT HARJIVANDAS TREASURY OFFICE LUMBHANI DIRECTOR OF REGIONAL FINANCE 69890111031 1 PARSOTTAM SUB AUDITOR ACCOUNTS & TRANSPORT 26 12 38 FAIL 26/09/2007 DEPARTMENT JERAMBHAI TREASURY OFFICE KARLIYA DIRECTOR OF DISTRICT FINANCE 69890111032 1 HARESHKUMAR JUNIOR CLERK ACCOUNTS & TREASURY 30 6 36 FAIL 26/09/2007 DEPARTMENT KHEMABHAI TREASURY OFFICE OFFICE OF THE BHIL PORT AND GUJARAT CHIEF 10190134001 1 REKHA GUJARATI TYPIST TRANSPORT MARITIME BOARD 34 18 52 FAIL 03/10/2007 EXECUTIVE KANUBHAI DEPARTMENT GANDHINAGAR OFFICER OFFICE OF THE BODAT PORT AND GUJARAT CHIEF 10190134002 1 NAYANA ENGLISH TYPIST TRANSPORT MARITIME BOARD 29 20 49 FAIL 03/10/2007 EXECUTIVE SHAKARABHAI DEPARTMENT GANDHINAGAR OFFICER OFFICE OF THE RATHOD PORT AND GUJARAT CHIEF 10190134003 1 DEVENDRASINH JUNIOR CLERK TRANSPORT MARITIME BOARD 28 26 54 PASS 03/10/2007 EXECUTIVE NATHUSINH DEPARTMENT GANDHINAGAR OFFICER OFFICE OF THE DANANI PORT AND GUJARAT CLERK CUM CHIEF 10190134004 1 JAWAHAR TRANSPORT MARITIME BOARD 28 27 55 PASS 03/10/2007 TYPIST EXECUTIVE RAMCHAND DEPARTMENT GANDHINAGAR OFFICER OFFICE OF THE JAYCHANDRAN PORT AND GUJARAT CHIEF 10190134005 1 M. -

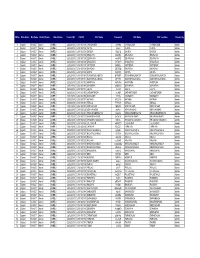

Rajkot -Passwords

SR No State Name Div Name District Name Block Name Created On CSC ID CSC Name Password VLE Name CSC Location Created By 1 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300101 CHANDGADH 0VPNts CHANDGADH CHANDGADH Admin 2 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300102 CHITAL rvrmrn CHITAL CHITAL Admin 3 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300103 DAHIDA HXg2Hq DAHIDA DAHIDA Admin 4 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300104 DEVALIYA DwLqBn DEVALIYA DEVALIYA Admin 5 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300105 DEVRAJIYA enoQFE DEVRAJIYA DEVRAJIYA Admin 6 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300106 DHOLARVA 5VFdmH DHOLARVA DHOLARVA Admin 7 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300107 FATTEPUR AMRELI FATTEPUR FATTEPUR Admin 8 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300108 GAVADKA SBGPgd GAVADKA GAVADKA Admin 9 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300109 GIRIYA fkAETW GIRIYA GIRIYA Admin 10 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300110 GOKHARVALA MOTA dYFVWT GOKHARVALA MOTA GOKHARVALA MOTA Admin 11 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300111 GOKHARVALA NANA gFTY02 GOKHARVALA NANA GOKHARVALA NANA Admin 12 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300112 HARIPURA AbPuGw HARIPURA HARIPURA Admin 13 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300113 ISHVARIYA 6MUeX5 ISHVARIYA ISHVARIYA Admin 14 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300114 JALIYA 1CzoYI JALIYA JALIYA Admin 15 Gujarat RAJKOT Amreli AMRELI 22/02/2010 GJ031300115 JASVANTGADH noJABY JASVANTGADH JASVANTGADH -

N GOVT- of Mnj^^Fsg

MS. I* -n * ^j GOVERNMENT OF INDIA \ WHITE PAPER ON INDIAN STATES >»rp^ONAL LIBRARY ©P „„»—» GOVT- OF mnj^^fSg Price Be. 1 -4*. 13 *r 2s. 65 21 PERSONAL LIBRARY OP PROFESSOR SHER SINGH "SHHH TABLE OF CONTENTS £age FOREWORD PART I.—INDIAN STATES UNDER PARAMOUNTCY OF THE BRITISH CROWN General Survey « 3 Historical Survey 4 Geographical Survey . • . 4 Political Diversity of States. 5 Three Categories of States 5 Chamber of Princes. 6 Treaties, Engagements and Sanads ....... 6 Relationship between Paramount Power and Indian States. 6 PART n.—THE STATES UNDER THE SCHEME OF THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ACT, 1935, AND SUBSEQUENT PLANS FOR INDIA'S CONSTITU TIONAL ADVANCEMENT. Federal Scheme 7 Cripps Plan 8 Simla Conference of 1945 9 Cabinet Mission's Plan 9 His Majesty's Government's Statement of June 3, 1947. 11 PART ni.—ACCESSION OF THE STATES TO THE DOMINION OF INDIA. Lapse of Paramountcy ......... 12 States Department ......... 12 Necessity of a Common Centre '......• 13 Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel's Statement of July 5, 1947. 13 special Meeting of Princes on July 25, 1947 .' 1^ Successful conclusion of Negotiations ...... 14 Instrument of Accession ......•• 14 standstill Agreements . • m m • 15 significance of Constitutional Relationship between the Indian Dominion and the States 15 PART IV.—INTEGRATION AND Problem of Smaller States 15 Popular Movements in States 16 Merger of Orissa and Chattisgarh States • 16 Hon'ble States Minister's Statement on Policy of Integration and Democratisation ........••• 17 Merger of Deccan States. .....••• 18 Merger of Gujarat States ......•• 18 Merger of other small States .••••••• 19 Consolidation of East Punjab Hill States into a Centrally Administered Unit 19 Merger of Kutch 19 Formation of Unions 20 T" :f ed State of Kathiawar (Saurashtra) . -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered As a Newspaper at the G.P.O.)

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXIX—No. 41 NAIROBI, 31st March, 2017 Price Sh. 60 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 3101 4TH ANNUAL REPORT 2016 ON MEASURES TAKEN AND PROGRESS ACHIEVED IN THE REALIZATION OF NATIONAL VALUES AND PRINCIPLES OF GOVERNANCE LIST OF ABREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ACA Anti-Counterfeit Agency ACE Adult and Continuing Education ACUs Aids Control Units ADA Alcohol and Drug Abuse ADC Agriculture Development Corporation ADEA Association for the Development of Education AFA Agriculture and Food Authority AFAP Africa Fertilizer Agribusiness Partnership AFC Agricultural Finance Corporation AGPO Access to Government Procurement Opportunities AGRA Alliance for Green Revolution in Africa AMISOM African Union Mission in Somalia APSD African Public Service Day ARA Assets Recovery Agency ASALs Arid and Semi-Arid Lands ASK Agricultural Society of Kenya AWSB Athi Water Services Board CAADP Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme CAD Fund China Africa Development Fund CAJ Commission on Administrative Justice CAK Competition Authority of Kenya CARPS Capacity Assessment and Rationalization of the Public Service CBA Collective Bargaining Agreement CBIK Centre for Business Information Kenya CBK Central Bank of Kenya CBO Community Based Organizations CBR Central Bank Rate CDFC Constituency Development Fund Committee CEC County Executive Committee CIDCs Constituency Industrial Development Centers CIDP County Integrated Development Plan CIM Chartered -

Kenyan Diplomatic Relations

Sumerianz Journal of Social Science, 2019, Vol. 2, No. 10, pp. 170-185 ISSN(e): 2616-8693, ISSN(p): 2617-1716 Website: https://www.sumerianz.com © Sumerianz Publication CC BY: Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 Original Article Open Access Character Development Challenges and Opportunities Influencing Anglo- Kenyan Diplomatic Relations Dr. Elijah Onyango Standslause Odhiambo Department of Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Masinde Muliro University of Science Technology and Anglican Diocese of Bondo, Kenya Abstract Military professionalism has three characteristic: expertise, social responsibility and corporateness. Education is a universal characteristic of all professions, including the military profession. Indeed, if a long-term military career is foreseen, one that will culminate in high rank, officers are advised to pursue a robust professional program. Military officers should have the intellectual expertise required to employ a nation's armed forces all its military resources in support of and within the larger totality of a nation's security. They have to understand and deal with military relations and other aspects like military, economic, technological and other societal changes in an intellectual manner. While the independence period has witnessed cordial diplomatic, trade and economic relations between the two countries, the ideal military professionalism is a key factor in interstate diplomatic relations. Anglo-Kenyan diplomatic relations has been beset with challenges embedded in military professionalism on both sides. These include challenges in character development in terms of military relations. Specifically the study sought to: examine character development challenges and opportunities influencing Anglo-Kenyan diplomatic relations. The study was based on a theoritical frame work that encompassed realist theory. -

Kenya Defence Forces Athletics Championship 2019

ATHLETICS KENYA DEFENCE FORCES (Affiliated to Athletics Kenya) The 40th Edition of KENYA DEFENCE FORCES ATHLETICS CHAMPIONSHIP 2019 at Moi International Sports Centre Kasarani Final Results Sponsored by Psn Name BIB DOB Fmn Mark 100m Women Final 1 TECLA JEROTICH 702 1997 TKA 12.54 2 QUEENECTER N KISEMBE 1101 1990 LAB 12.55 3 PATRICIA ISICHI 204 1994 MDK 12.56 4 CATHERINE NANDI 001 1986 LNT 12.85 5 ANN KARANJA 800 1991 KAH 12.86 6 BEATRICE CHERONO 801 1997 KAH 12.95 7 MARY TANUI 701 1987 TKA 13.00 8 PURITY NDUKO 1001 1997 MAB 13.06 100m Men Final 1 SAMWEL CHEGE 1208 1998 MTG 10.39 2 GILBERT OSURE OTIENO 520 1991 ISL 10.63 3 MAURICE WASIKE 116 1993 NKI 10.66 4 WALTER MOENGA 715 1987 TKA 10.67 5 CHARLES WAMWEA 716 1988 TKA 10.70 6 CARLEWIS AWANGE 814 1989 KAH 10.72 7 PETER MAKUBA 1209 1987 MTG 10.95 8 KIPKEMOI SOI 815 1984 KAH 10.99 9 MATHEW MATAYO 1020 1993 MAB DSQ 100m Hurdles Women Final 1 . JERIOTH GATHOGO 1104 1996 LAB 14.5 2 . PRISCILA TABUNDA 511 1984 ISL 14.6 3 . JANE CHEGE 1204 1998 MTG 14.8 4 . JELAGAT BRIDGIT 203 1999 MDK 15 5 . BRENDA MUREMI 1205 1998 LAB 15.4 6 . ELIZABETH KIMUYU 1004 1998 MAB 16.1 7 . BETTY KIPKETER 321 1994 MAR 20.1 110m Hurdles Final Men 1 WILLIAM MBEVI 1118 1992 LAB 14.05 2 MICHAEL MUSYOKA 513 1996 ISL 14.08 3 VINCENT TARUS 1117 1993 LAB 15.02 4 ELIJAH CHESOENI 816 1986 KAH 15.05 5 WILSON WAHOME 020 1986 LNT 15.08 6 EMMANUEL PANDE 405 1995 GIL 16.02 7 HEZRON YEGON 908 1992 NBI 17.07 8 MARK NGETICH 1026 MAB 17.09 200m Women Final WS -1.4M/S 1 QUEENECTER N KISEMBE 1101 1990 LAB 25.24 2 NAOMI KIPLANGAT 002 -

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze Zestawienie Zawiera 8372 Kody Lotnisk

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze zestawienie zawiera 8372 kody lotnisk. Zestawienie uszeregowano: Kod ICAO = Nazwa portu lotniczego = Lokalizacja portu lotniczego AGAF=Afutara Airport=Afutara AGAR=Ulawa Airport=Arona, Ulawa Island AGAT=Uru Harbour=Atoifi, Malaita AGBA=Barakoma Airport=Barakoma AGBT=Batuna Airport=Batuna AGEV=Geva Airport=Geva AGGA=Auki Airport=Auki AGGB=Bellona/Anua Airport=Bellona/Anua AGGC=Choiseul Bay Airport=Choiseul Bay, Taro Island AGGD=Mbambanakira Airport=Mbambanakira AGGE=Balalae Airport=Shortland Island AGGF=Fera/Maringe Airport=Fera Island, Santa Isabel Island AGGG=Honiara FIR=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGH=Honiara International Airport=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGI=Babanakira Airport=Babanakira AGGJ=Avu Avu Airport=Avu Avu AGGK=Kirakira Airport=Kirakira AGGL=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova Airport=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova, Santa Cruz Island AGGM=Munda Airport=Munda, New Georgia Island AGGN=Nusatupe Airport=Gizo Island AGGO=Mono Airport=Mono Island AGGP=Marau Sound Airport=Marau Sound AGGQ=Ontong Java Airport=Ontong Java AGGR=Rennell/Tingoa Airport=Rennell/Tingoa, Rennell Island AGGS=Seghe Airport=Seghe AGGT=Santa Anna Airport=Santa Anna AGGU=Marau Airport=Marau AGGV=Suavanao Airport=Suavanao AGGY=Yandina Airport=Yandina AGIN=Isuna Heliport=Isuna AGKG=Kaghau Airport=Kaghau AGKU=Kukudu Airport=Kukudu AGOK=Gatokae Aerodrome=Gatokae AGRC=Ringi Cove Airport=Ringi Cove AGRM=Ramata Airport=Ramata ANYN=Nauru International Airport=Yaren (ICAO code formerly ANAU) AYBK=Buka Airport=Buka AYCH=Chimbu Airport=Kundiawa AYDU=Daru Airport=Daru -

Republic of Kenya

REPUBLIC OF KENYA MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT &FORESTRY STATE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT KENYAMETEOROLOGICALDEPARTMENT Dagoretti Corner, Ngong Road, P. O. Box 30259, 00100 GPO, Nairobi, Kenya Telephone: 254 (0) 20 3867880-7,Fax: 254 (0) 20 3876955/3877373/3867888, e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Website: http://www.meteo.go.ke WEATHER FORECAST FOR THE NEXT SEVEN-DAY PERIOD VALID 20TH TO 26TH MARCH, 2018 Review of weather for the last seven- Forecast for the next seven days day period (12thto 18thMarch, 2018): (20th to 26th March, 2018): The forecast indicates that: Wet conditions were sustained over most parts of Issue Date: 19/03/2018 the country with a marked increase in rainfall Rainfall is expected to continue over several parts amounts over various regions during the review of the country during the first two days of the forecast period; period; A reduction in rainfall amounts is expected over Day-time (maximum) temperatures decreased most areas between Wednesday and Friday throughout the country while night-time followed by an increase again from Saturday. (minimum) temperatures generallyincreased. 1. WEATHER REVIEW FOR THE LAST SEVEN DAYS (12TH TO 18TH MARCH, 2018) 1.1 Rainfall Review Wet conditions were sustained over most parts of the country as depicted in Figures 1, 2 and 3and some areas exhibited a marked increase in rainfall. Mrangi Primary School (in Taita Taveta County) recorded the highest amount of rainfall within 24 hours of 138.0mm on 16thMarch, 2018. Other stations that reported very heavy rainfall (>50mm)within 24 hours on various days include Iten (97.8mm), Busia Ministry of Water (94.9mm), Mabanga A.T.C (91.0mm), Kabete (74.0mm), Shigharo (66.2mm), Wilson Airport (58.5mm), Garissa (51.2mm), Kisii (51.0mm), Dagoretti (50.1mm), . -

INDIAN STATES C

/ « < 9 3 7LU 1. 5,0007 9 9 9 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ■ 3 o 9 ci> WHITE PAPER 4 <^ON cs INDIAN STATES c 9 9 » • \ 00108841 J < PRlNl^ Ili INDIA BY THE MANAQ^ GOVT. OF INDIA PB3SS, NSW DELHI JULY 1948 a « Price lie. 1 -Id. 12 or 6. f. o . 0 t <9 • •. *« 9 BOMBAY branch ‘ ©» xKs lb , I™ ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY. I; I HALL, iKtebAY. I ( Digitized with financial assistance from Government of Maharashtra on 01 February, 2020 < TABLE OP CONTENTS Pago. • • ^FOREWORD . -108841 /^ 1 PART I.—INDIAN STATES UNDER PARAMOUNTCY OF THE BRITISH CROWN General Survey. • • ' 3 Historical Survey . • a 4 GeograpEidkl Survey 4 Political Diversity of States. • • a 5 Three Categories of States 6 Chamber of Princes. »' 5 Treaties, Engagements and Sanads . 5 Relationship between Paramount Power and Indian States. 6 PART II.—THE STATES UNDER THE SCHEME OF THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ACT, 1935, AND SUBSEQUENT PLANS FOR INDIA’S CONSTITU TIONAL ADVANCEMENT. Federal Scheme 7 Cripps Plan 8 Simla Conferenc'j of 1945 9 Cabinet Mission'S Plan 9 His Majesty’s Government’s Statement of June 3,1947. 11 PART III.—ACCESSION OF THE STATES TO THE DOMINION OF INDIA. Lapse of Paramountcf . 12 States Department ...... 12 Necessity of a Common Centre * • • 13 Sardar VaUabhbhai Patel’s Stateifent of July 5, 1947. 13 Special Meeting of Princes on July 2^ 1947. 13 Successful conclusion of Negotiations . 14 Instrument of Accession . • ' 14 Standstill Agreenwits . .♦ 1,5 . Significance of Constitutional Relationship between the Indian Dominion and the tales. ......... 15 PART IV.—INTEGRATION AND DEMOCRATISATION OF STATES.