Faculty Credentials & Qualifications Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gapsc Certificate Level Upgrade Rule Guidance

GaPSC Certificate Level Upgrade Rule 505-2-.41 GUIDANCE FOR EDUCATORS Introduction and Use of This Document In Georgia the Professional Standards Commission (GaPSC) is the state agency authorized to assume full responsibility for the certification, preparation and conduct of certified, licensed or permitted education personnel employed in Georgia, and the development and administration of educator certification testing. The GaPSC's authority applies to certified, licensed and permitted personnel employed in Georgia public schools and institutions of higher learning that prepare educators. This document is intended to provide guidance to educators regarding the implementation of GaPSC Rule 505-2-.41, Educator Certificate Upgrades. Foci of this guidance document include: Ensuring educators understand Rule 505-2-.41 Explaining how Rule 505-2-.41 affects Georgia educators; and Providing links to other relevant and important documents or resources. Organized by the foci listed above, topics and relevant links are provided in the order and locations referenced below. E-mail suggested additions or improvements to this document to Dr. Bobbi Ford at [email protected]. Topics Pages Section I: Key Components of Rule 505-2-.41 2 - 3 Section II: Advanced Degree Program Options and Requirements 3 - 9 A. Program Options B. In-Field Upgrade Requirements C. New Field Upgrade Requirements D. Three New Fields of Certification E. Grandfathering Timelines F. Voluntary Deletion of Certificate Section III: Seeking Advisement 9 - 10 Section IV: Appendices -

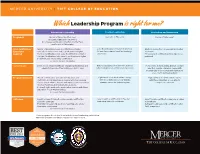

Whichleadership Program Is Right For

MERCER UNIVERSITY | TIFT COLLEGE OF EDUCATION Which Leadership Program is right for me? Educational Leadership Teacher Leadership Curriculum and Instruction Program(s) Master of Education (Tier One), Specialist in Education Doctor of Philosophy* Specialist in Education (Tier Two), Non-Degree Certification Only (Tier One, Tier Two), and Doctor of Philosophy* Prior Certification/ • Master of Education: Level 4 certification or higher • Level 5 certification or higher in any field • Master’s degree from a regionally accredited Experience • Specialist in Education: Level 5 certification or higher • At least three years of certified teaching institution Required • Tier One Certification Only: Level 5 certification or higher experience • Three years of certified teaching experience • Tier Two Certification Only: Level 6 certification or higher preferred • Doctoral: Level 6 leadership certification See reverse for more information. Career Goals Enter into or advance within an educational leadership and Enter a leadership or mentor role without Pursue roles at the building, district, or state administration role at the building or district level fully moving into an administration position level that require a terminal degree with an emphasis on curriculum and instruction assessment and development Program Structure • Master of Education, Specialist in Education, and Eight-week or 16-week online courses Eight-week or 16-week online courses Certification Only: Eight-week courses with four evening with three Saturdays on our Atlanta with three Saturdays on our Atlanta classes at our Atlanta, Macon, and Henry County locations† campus across the entire program campus per semester and four field-based clinical practice sessions • Doctoral: Eight-week or 16-week online courses with three Saturdays on our Atlanta campus See reverse for more information. -

The Graduate Faculty Handbook, 1992)

1 THE GRADUATE FACULTY HANDBOOK SCHOOL OF GRADUATE & PROFESSIONAL STUDIES TENNESSEE STATE UNIVERSITY NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE Revised 9/28/2018 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS SCHOOL OF GRADUATE & PROFESSION STUDIES ......................................................................... 3 Goals of the School of Graduate & Professional Studies................................................... 5 ADMINISTRATION OF THE GRADUATE PROGRAMS ..................................................................... 6 GRADUATE FACULTY ................................................................................................................... 7 Policy on Certification of Full Graduate Faculty Membership ........................................... 7 Application for Full Graduate Faculty Membership ........................................................ 10 Policy on Re-certification of Full Graduate Faculty membership .................................... 13 Application for Re-certification to Full Graduate Faculty Membership ........................... 15 Policy on Certification of Associate Graduate Faculty .................................................... 18 Application for Associate Level 1 Graduate Faculty Membership ................................... 19 Application For Associate Level 2 Graduate Faculty Membership .................................. 20 Policy on Adjunct Graduate Faculty Membership .......................................................... 22 Application For Adjunct Graduate Faculty Membership ................................................ -

The Professional Bachelor – Law

The Professional Bachelor – Law National professional and degree programme profile for the Professional Bachelor - Law 2012 Credits The Professional Bachelor - Law National professional and degree programme profile for the Professional Bachelor - Law CROHO: 39205 The Professional Bachelor - Law Publication: July 2012 Adopted by the National Consultative Committee for the professional Bachelors of Laws degree programme (HBO-Rechten), in which the following universities of applied sciences (Hogescholen) participate: • Haagse Hogeschool • Hanzehogeschool Groningen • Hogeschool van Amsterdam • Hogeschool van Arnhem en Nijmegen • Hogeschool Inholland • Hogeschool Leiden • Hogeschool Utrecht • Fontys Hogescholen (Juridische Hogeschool) • Avans Hogeschool (Juridische Hogeschool) • Hogeschool Windesheim • Noordelijke Hogeschool Leeuwarden Drawn up by the working group for updating the national professional and following persons: degree• programmeG.F.J. Hupperetz, profile LL.M. for he (Director Professional of Juridische Bachelor Hogeschool - Law, comprising Avans- the Fontys), chairman of the National Consultative Committee for the professional Bachelors of Laws degree programme • T.J.M. Joxhorst, LL.M. (Team leader Professional Bachelor - Law Hanzehogeschool) • Drs. M. Kok (Educationalist at the Hogeschool van Amsterdam) • E.M.Oudejans, LL.M. (Professional Bachelor of Laws degree programme manager at the Hogeschool van Amsterdam), chairman of the working group • R.A. Plantenga, LL.M. (Team leader for Professional Bachelor - Law at Haagse Hogeschool) -

LL.B. to J.D. and the Professional Degree in Architecture

85THACSA ANNUAL MEETING ANDTECHNOLOGY (ONFEKtNCE 585 LL.B. to J.D. and the Professional Degree in Architecture JOANNA LOMBARD University of Miami Thirty-four years ago, the American Bar Association (ABA) (I) that the lack of uniformity in nolnenclature was recotrunended that Ainerican law schools offer a single confusing to the public and (2) that the J.D. terminol- unified professional degree, the Juris Doctor. Sixty years of ogy inore accurately described the relevant academic sporadic discussion and debate preceded that reconmenda- accomplishment at approved law schools. The Sec- tion. The Bachelor of Laws (LL.B.) had originated as an tion, therefore, recommended that such schools con- undergraduate prograln which evolved over time to graduate fer the degree of Juris Doctor (J.D.) . on those studies while retaining the bachelor's degree designation. In students who successfully coinplete the prograln recognition of the relatively unifonn acceptancc of the 3- leading to the first professional degree in law year graduate prograln as thc first professional degree in law (decapriles 1967, 54). in thc 1960's, a number of law faculty and administrators By 1967, nearly half the law schools had colnplied with the argued for a national consensus confinning the three-year 1964 ABA resolution: a nulnber of law faculty and admin- graduate prograln and changing the first professional degrce istrators continued the debate(deCapri1es 1967, 54). Within from an LL.B. to the J.D. (Doctor of Law). The debate among the next five years, the J.D. emerged as the single, first law faculty and the process through which change occurred professional degree in law and today the J.D. -

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities American Council of Learned Societies ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 59 In Memory of Christina Elliott Sorum 1944-2005 Copyright © 2005 American Council of Learned Societies Contents Introduction iii Pauline Yu Prologue 1 The Liberal Arts College: Identity, Variety, Destiny Francis Oakley I. The Past 15 The Liberal Arts Mission in Historical Context 15 Balancing Hopes and Limits in the Liberal Arts College 16 Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz The Problem of Mission: A Brief Survey of the Changing 26 Mission of the Liberal Arts Christina Elliott Sorum Response 40 Stephen Fix II. The Present 47 Economic Pressures 49 The Economic Challenges of Liberal Arts Colleges 50 Lucie Lapovsky Discounts and Spending at the Leading Liberal Arts Colleges 70 Roger T. Kaufman Response 80 Michael S. McPherson Teaching, Research, and Professional Life 87 Scholars and Teachers Revisited: In Continued Defense 88 of College Faculty Who Publish Robert A. McCaughey Beyond the Circle: Challenges and Opportunities 98 for the Contemporary Liberal Arts Teacher-Scholar Kimberly Benston Response 113 Kenneth P. Ruscio iii Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education II. The Present (cont'd) Educational Goals and Student Achievement 121 Built To Engage: Liberal Arts Colleges and 122 Effective Educational Practice George D. Kuh Selective and Non-Selective Alike: An Argument 151 for the Superior Educational Effectiveness of Smaller Liberal Arts Colleges Richard Ekman Response 172 Mitchell J. Chang III. The Future 177 Five Presidents on the Challenges Lying Ahead The Challenges Facing Public Liberal Arts Colleges 178 Mary K. Grant The Importance of Institutional Culture 188 Stephen R. -

General Criteria Used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I

General Criteria used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I. Rationale A majority of universities that award graduate degrees have established procedures to identify faculty members specifically qualified to train students in advanced degree programs. These members are then identified as the Graduate Faculty. The main responsibilities of the Graduate Faculty are to conduct scholarly research and creative work of high quality, to teach graduate students effectively, to advise graduate students, and to direct the research of graduate students. Listed below are the University-wide performance expectations for those faculty who have these responsibilities at Clayton State University. II. Expectations for Current Graduate Faculty Members Members of the Graduate Faculty at Clayton State University must continually satisfy both University-wide standards and those specific to individual academic components. No single performance criterion should be used to judge the fitness of a member. The primary consideration is whether the faculty member is currently an active and productive scholar and sufficiently prepared to teach at the graduate level. The University-wide performance expectations for current members are as follows: A. Scholarship 1. Possession of the terminal academic degree in the member’s field and ability to submit proof of said degree or recognition for substantive and distinctive contributions to the discipline involved. 2. Evidence of current involvement in scholarly research and/or creative activity. This evidence may consist of the publication of books and refereed articles, obtainment of research grants and contracts, recitals, exhibitions, performances, or other demonstrations of scholarship appropriate to the discipline. B. Intellectual Leadership 1. Active participation in regional, national, or international meetings in or related to the respective discipline. -

On Professional Degree Requirement for Civil Engineering Practice

Session 2515 ON PROFESSIONAL DEGREE REQUIREMENT FOR CIVIL ENGINEERING PRACTICE James T. P. Yao, Loren D. Lutes Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas I. Introduction In May 1998, ASCE NEWS announced that the Board of Direction “approved a resolution endorsing the master’s degree as the first professional degree for the practice of civil engineering.” The July 1998 ASCE NEWS clarified the earlier article by quoting the definition of the “first professional degree” used by the U.S. Department of Education. It is defined as “a degree that signifies both completion of the academic requirements for beginning practice in a given profession and a level of professional skill beyond that normally required for a bachelor’s degree.” Such a degree is generally required for dentists, physicians, pharmacists, lawyers, theologians, and architects. It is usually based on a total of at least six academic years of work. Arguments that have advanced for considering such a professional degree for civil engineering practice include: • The bachelor’s degree is no longer adequate preparation for civil engineering practice. • This change would improve the professional stature of civil engineers and thus improve the compensation of practitioners. • It would provide a clear distinction between civil engineering graduates and technicians. The same July 1998 article reported that the ASCE Board of Direction is contemplating promotion of a policy being prepared by the Educational Activities Committee. Also, the Board may decide to seek support from such organizations as the Accreditation Board of Engineering and Technology, the National Society of Professional Engineers, and the National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying. -

Liberal Arts Education and Information Technology

VIEWPOINT Liberal Arts Education and Information Technology: Time for Another Renewal Liberal arts colleges must accommodate the powerful changes that are taking place in the way people communicate and learn by Todd D. Kelley hree significant societal trends and that institutional planning and deci- Five principal reasons why the future will most certainly have a broad sion making must reflect the realities of success of liberal arts colleges is tied to Timpact on information services rapidly changing information technol- their effective use of information tech- and higher education for some time to ogy. Boards of trustees and senior man- nology are: come: agement must not delay in examining • Liberal arts colleges have an obliga- • the increasing use of information how these changes in society will impact tion to prepare their students for life- technology (IT) for worldwide com- their institutions, both negatively and long learning and for the leadership munications and information cre- positively, and in embracing the idea roles they will assume when they ation, storage, and retrieval; that IT is integral to fulfilling their liberal graduate. • the continuing rapid change in the arts missions in the future. • Liberal arts colleges must demon- development, maturity, and uses of (2) To plan and support technological strate the use of the most significant information technology itself; and change effectively, their colleges must approaches to problem solving and • the growing need in society for have sufficient high-quality information communications to have emerged skilled workers who can understand services staff and must take a flexible and since the invention of the printing and take advantage of the new meth- creative approach to recruiting and press and movable type. -

Russia Country Statistics Population: 142,257,519 (July 2017 Est.) Ethnic Groups: Russian 78%, Tatar 4%, Other 18%

Russia Country Statistics Population: 142,257,519 (July 2017 est.) Ethnic Groups: Russian 78%, Tatar 4%, Other 18% Religions: Russian Orthodox 15-20%, Muslim 10-15%, Other 70-60% Languages: Russian (official) 86%, Tatar 4%, Other 10% Area: 17,098,242 sq km (approximately 1.8 times the size of the US) Government Type: Semi-Presidential Federation National Capital: Moscow Currency: Russian Rubles (RUB) Educational System Grading Scale – All Levels Secondary Reported Grade Translation US Certificate of Basic General Education Grades 1-9 Equiv Аттестат об основном общем образовании 5 Отлично Excellent A Attestat ob osnovnom obschem obrazovanii Otlichno Certificate of (Complete) General Secondary Education Grades 10-11 4 Хорошо Good B Аттестат о среднем (полном) общем образовании Khorosho Attestat o srednem (polnom) obschem obrazovanii 3 Удовлетворительно Satisfactory C Udovletvoritel’no Postsecondary 2 Неудовлетвори- Unsatisfactory F Russia is a member of the European Higher Education Area and is part of the Bologna Process as of 2003. тельно Bachelor’s Diploma 4 years Neudovletvoritel’no Диплом бакалавра 1 Неудовлетвори- Unsatisfactory F Diplom Bakalavra тельно Specialist’s Diploma 5-6 years Neudovletvoritel’no Диплом специалиста] – Зачет Pass P Diplom Spetsialista Zachet Master’s Diploma 2 years Диплом магистра Diplom Magistra Diploma of Candidate of Sciences 3 or more years Диплом кандидата наук Diplom Kandidata Nauk IU Placement Recommendations Freshman • Certificate of (Complete) General Secondary Education Transfer • 1-3 years undergraduate study • Specialist’s Degree program when a graduation certificate was not obtained Graduate • Bachelor’s Diploma • Specialist’s Diploma when a graduation certificate was obtained Required Academic Records Undergraduate Applications • Lower Secondary School Transcript o For Grade 9 • Upper Secondary Transcript • Certificate of (Complete) General Secondary Education Graduate Applications For transcripts, alternatively we can accept the Diploma Supplement if accompanied by the degree certificate. -

The Magisterium of the Faculty of Theology of Paris in the Seventeenth Century

Theological Studies 53 (1992) THE MAGISTERIUM OF THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY OF PARIS IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY JACQUES M. GRES-GAYER Catholic University of America S THEOLOGIANS know well, the term "magisterium" denotes the ex A ercise of teaching authority in the Catholic Church.1 The transfer of this teaching authority from those who had acquired knowledge to those who received power2 was a long, gradual, and complicated pro cess, the history of which has only partially been written. Some sig nificant elements of this history have been overlooked, impairing a full appreciation of one of the most significant semantic shifts in Catholic ecclesiology. One might well ascribe this mutation to the impetus of the Triden tine renewal and the "second Roman centralization" it fostered.3 It would be simplistic, however, to assume that this desire by the hier archy to control better the exposition of doctrine4 was never chal lenged. There were serious resistances that reveal the complexity of the issue, as the case of the Faculty of Theology of Paris during the seventeenth century abundantly shows. 1 F. A. Sullivan, Magisterium (New York: Paulist, 1983) 181-83. 2 Y. Congar, 'Tour une histoire sémantique du terme Magisterium/ Revue des Sci ences philosophiques et théologiques 60 (1976) 85-98; "Bref historique des formes du 'Magistère' et de ses relations avec les docteurs," RSPhTh 60 (1976) 99-112 (also in Droit ancien et structures ecclésiales [London: Variorum Reprints, 1982]; English trans, in Readings in Moral Theology 3: The Magisterium and Morality [New York: Paulist, 1982] 314-31). In Magisterium and Theologians: Historical Perspectives (Chicago Stud ies 17 [1978]), see the remarks of Y. -

OAKWOOD UNIVERSITY Faculty Handbook

FACULTY HANDBOOK OAKWOOD UNIVERSITY Faculty Handbook (Revised 2008) Faculty Handbook Page 1 FACULTY HANDBOOK Table of Contents Section I General Administration Information Oakwood University Mission Statement ........................................................................................... 5 Historic Glimpses .............................................................................................................................. 5 Accreditation ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Affirmative Action and Religious Institution Exemption .................................................................. 6 Sexual Harassment ............................................................................................................................. 6 Drug-free Environment ...................................................................................................................... 7 Establishment and Dissolution of Departments and Majors .............................................................. 8 Section II Policies Governing Faculty Functions Faculty Classifications ...................................................................................................................... 10 Academic Rank ................................................................................................................................. 11 Promotions .......................................................................................................................................