Living Without Copyright in a Digital World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eliciting Informative Feedback: the Peer$Prediction Method

Eliciting Informative Feedback: The Peer-Prediction Method Nolan Miller, Paul Resnick, and Richard Zeckhauser January 26, 2005y Abstract Many recommendation and decision processes depend on eliciting evaluations of opportu- nities, products, and vendors. A scoring system is devised that induces honest reporting of feedback. Each rater merely reports a signal, and the system applies proper scoring rules to the implied posterior beliefs about another rater’s report. Honest reporting proves to be a Nash Equilibrium. The scoring schemes can be scaled to induce appropriate e¤ort by raters and can be extended to handle sequential interaction and continuous signals. We also address a number of practical implementation issues that arise in settings such as academic reviewing and on-line recommender and reputation systems. 1 Introduction Decision makers frequently draw on the experiences of multiple other individuals when making decisions. The process of eliciting others’information is sometimes informal, as when an executive consults underlings about a new business opportunity. In other contexts, the process is institution- alized, as when journal editors secure independent reviews of papers, or an admissions committee has multiple faculty readers for each …le. The internet has greatly enhanced the role of institu- tionalized feedback methods, since it can gather and disseminate information from vast numbers of individuals at minimal cost. To name just a few examples, eBay invites buyers and sellers to rate Miller and Zeckhauser, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University; Resnick, School of Information, University of Michigan. yWe thank Alberto Abadie, Chris Avery, Miriam Avins, Chris Dellarocas, Je¤ Ely, John Pratt, Bill Sandholm, Lones Smith, Ennio Stachetti, Steve Tadelis, Hal Varian, two referees and two editors for helpful comments. -

The Music Industry and Digital Music

The Music Industry and Digital Music Disruptive Technology and the Value Network Effects on Industry Incumbents A thesis written by Jens Peter Larsen Cand. Merc., Master of Science, Management of Innovation & Business Development Copenhagen Business School Supervisor: Finn Valentin, Institut for innovation og organisationsøkonomi Word Count: 170.245 digits – 75 standard pages The Music Industry and Digital Music – Jens Peter Larsen, Cand. Merc. MIB Thesis Table of Content 1. Resume .................................................................................. 4 2. Introduction ............................................................................ 5 3. Research Design ....................................................................... 6 3.1 Research Question .......................................................................................................... 6 3.2 Elaboration on Research Design ................................................................................... 6 3.2.1 Technological Development ..................................................................................... 6 3.2.2 Definitions................................................................................................................. 7 4. Methodology ............................................................................ 8 4.1 Project Outlook .............................................................................................................. 9 4.2 Delimitation .................................................................................................................. -

Crowdfunding Platforms: Ecosystem and Evolution Full Text Available At

Full text available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1561/1700000061 Crowdfunding Platforms: Ecosystem and Evolution Full text available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1561/1700000061 Other titles in Foundations and Trends® in Marketing Entertainment Marketing Natasha Zhang Foutz ISBN: 978-1-68083-332-4 The Cultural Meaning of Brands Carlos J. Torelli, Maria A. Rodas and Jennifer L. Stoner ISBN: 978-1-68083-286-0 Ethnography for Marketing and Consumer Research Alladi Venkatesh, David Crockett, Samantha Cross and Steven Chen ISBN: 978-1-68083-234-1 The Information-Economics Perspective on Brand Equity Tulin Erdem and Joffre Swait ISBN: 978-1-68083-168-9 Full text available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1561/1700000061 Crowdfunding Platforms: Ecosystem and Evolution Yee Heng Tan Tokyo International University Japan [email protected] Srinivas K. Reddy Singapore Management University Singapore [email protected] Boston — Delft Full text available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1561/1700000061 Foundations and Trends® in Marketing Published, sold and distributed by: now Publishers Inc. PO Box 1024 Hanover, MA 02339 United States Tel. +1-781-985-4510 www.nowpublishers.com [email protected] Outside North America: now Publishers Inc. PO Box 179 2600 AD Delft The Netherlands Tel. +31-6-51115274 The preferred citation for this publication is Y. H. Tan and S. K. Reddy. Crowdfunding Platforms: Ecosystem and Evolution. Foundations and Trends® in Marketing, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 53–172, 2020. ISBN: 978-1-68083-699-8 © 2020 Y. H. Tan and S. K. Reddy All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publishers. -

Annual Report 2018

2018Annual Report Annual Report July 1, 2017–June 30, 2018 Council on Foreign Relations 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10065 tel 212.434.9400 1777 F Street, NW, Washington, DC 20006 tel 202.509.8400 www.cfr.org [email protected] OFFICERS DIRECTORS David M. Rubenstein Term Expiring 2019 Term Expiring 2022 Chairman David G. Bradley Sylvia Mathews Burwell Blair Effron Blair Effron Ash Carter Vice Chairman Susan Hockfield James P. Gorman Jami Miscik Donna J. Hrinak Laurene Powell Jobs Vice Chairman James G. Stavridis David M. Rubenstein Richard N. Haass Vin Weber Margaret G. Warner President Daniel H. Yergin Fareed Zakaria Keith Olson Term Expiring 2020 Term Expiring 2023 Executive Vice President, John P. Abizaid Kenneth I. Chenault Chief Financial Officer, and Treasurer Mary McInnis Boies Laurence D. Fink James M. Lindsay Timothy F. Geithner Stephen C. Freidheim Senior Vice President, Director of Studies, Stephen J. Hadley Margaret (Peggy) Hamburg and Maurice R. Greenberg Chair James Manyika Charles Phillips Jami Miscik Cecilia Elena Rouse Nancy D. Bodurtha Richard L. Plepler Frances Fragos Townsend Vice President, Meetings and Membership Term Expiring 2021 Irina A. Faskianos Vice President, National Program Tony Coles Richard N. Haass, ex officio and Outreach David M. Cote Steven A. Denning Suzanne E. Helm William H. McRaven Vice President, Philanthropy and Janet A. Napolitano Corporate Relations Eduardo J. Padrón Jan Mowder Hughes John Paulson Vice President, Human Resources and Administration Caroline Netchvolodoff OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, Vice President, Education EMERITUS & HONORARY Shannon K. O’Neil Madeleine K. Albright Maurice R. Greenberg Vice President and Deputy Director of Studies Director Emerita Honorary Vice Chairman Lisa Shields Martin S. -

Remixology: an Axiology for the 21St Century and Beyond

Found Footage Magazine, Issue #4, March 2018 http://foundfootagemagazine.com/ Remixology: An Axiology for the 21st Century and Beyond David J. Gunkel – Northern Illinois University, USA Despite what is typically said and generally accepted as a kind of unquestioned folk wisdom, you can (and should) judge a book by its cover. This is especially true of my 2016 book with the MIT Press, Of Remixology: Ethics and Aesthetics After Remix (Gunkel 2016). With this book, the cover actually “says it all.” The image that graces the dust jacket (figure 1) is of a street corner in Cheltenham, England, where the street artist believed to be Banksy (although there is no way to confirm this for sure) appropriated a telephone booth by painting figures on a wall at the end of a line of row houses. This “artwork,” which bears the title “Spy Booth,” was then captured in a photographed made by Neil Munns, distributed by way of the Corbis image library, and utilized by Margarita Encomienda (a designer at MIT Press) for the book’s cover. The question that immediately confronts us in this series of re-appropriations and copies of copies is simple: What is original and what is derived? How can we sort out and make sense of questions concerning origination and derivation in situations where one thing is appropriated, reused, and repurposed for something else? What theory of moral and aesthetic value can accommodate and explain these situations where authorship, authority, and origination are already distributed across a network of derivations, borrowings, and re-appropriated found objects? Figure 1 – Cover Image for Of Remixology (MIT Press 2016) The following develops a response to these questions, and it does so in three steps or movements. -

The Information Revolution Reaches Pharmaceuticals: Balancing Innovation Incentives, Cost, and Access in the Post-Genomics Era

RAI.DOC 4/13/2001 3:27 PM THE INFORMATION REVOLUTION REACHES PHARMACEUTICALS: BALANCING INNOVATION INCENTIVES, COST, AND ACCESS IN THE POST-GENOMICS ERA Arti K. Rai* Recent development in genomics—the science that lies at the in- tersection of information technology and biotechnology—have ush- ered in a new era of pharmaceutical innovation. Professor Rai ad- vances a theory of pharmaceutical development and allocation that takes account of these recent developments from the perspective of both patent law and health law—that is, from both the production side and the consumption side. She argues that genomics has the po- tential to make reforms that increase access to prescription drugs not only more necessary as a matter of equity but also more feasible as a matter of innovation policy. On the production end, so long as patent rights in upstream genomics research do not create transaction cost bottlenecks, genomics should, in the not-too-distant future, yield some reduction in drug research and development costs. If these cost re- ductions are realized, it may be possible to scale back certain features of the pharmaceutical patent regime that cause patent protection for pharmaceuticals to be significantly stronger than patent protection for other innovation. On the consumption side, genomics should make drug therapy even more important in treating illness. This reality, coupled with empirical data revealing that cost and access problems are particularly severe for those individuals who are not able to secure favorable price discrimination through insurance, militates in favor of government subsidies for such insurance. As contrasted with patent buyouts, the approach favored by many patent scholars, subsidies * Associate Professor of Law, University of San Diego Law School; Visiting Associate Profes- sor, Washington University, St. -

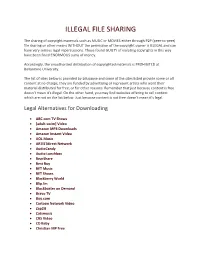

Illegal File Sharing

ILLEGAL FILE SHARING The sharing of copyright materials such as MUSIC or MOVIES either through P2P (peer-to-peer) file sharing or other means WITHOUT the permission of the copyright owner is ILLEGAL and can have very serious legal repercussions. Those found GUILTY of violating copyrights in this way have been fined ENORMOUS sums of money. Accordingly, the unauthorized distribution of copyrighted materials is PROHIBITED at Bellarmine University. The list of sites below is provided by Educause and some of the sites listed provide some or all content at no charge; they are funded by advertising or represent artists who want their material distributed for free, or for other reasons. Remember that just because content is free doesn't mean it's illegal. On the other hand, you may find websites offering to sell content which are not on the list below. Just because content is not free doesn't mean it's legal. Legal Alternatives for Downloading • ABC.com TV Shows • [adult swim] Video • Amazon MP3 Downloads • Amazon Instant Video • AOL Music • ARTISTdirect Network • AudioCandy • Audio Lunchbox • BearShare • Best Buy • BET Music • BET Shows • Blackberry World • Blip.fm • Blockbuster on Demand • Bravo TV • Buy.com • Cartoon Network Video • Zap2it • Catsmusic • CBS Video • CD Baby • Christian MP Free • CinemaNow • Clicker (formerly Modern Feed) • Comedy Central Video • Crackle • Criterion Online • The CW Video • Dimple Records • DirecTV Watch Online • Disney Videos • Dish Online • Download Fundraiser • DramaFever • The Electric Fetus • eMusic.com -

The Economics of Crowdfunding : Entrepreneurs’ and Platforms’ Strategies Jordana Viotto Da Cruz

The Economics of Crowdfunding : Entrepreneurs’ and Platforms’ Strategies Jordana Viotto da Cruz To cite this version: Jordana Viotto da Cruz. The Economics of Crowdfunding : Entrepreneurs’ and Platforms’ Strategies. Sociology. Université Sorbonne Paris Cité, 2017. English. NNT : 2017USPCD030. tel-01899518 HAL Id: tel-01899518 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01899518 Submitted on 19 Oct 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. |_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| UNIVERSITE PARIS 13 U.F.R. DE SCIENCES ÉCONOMIQUES ÉCOLE DOCTORALE : ERASME NO 493 THÈSE Pour obtention du grade de Docteur de l’Université Paris 13 Discipline : Sciences Économiques Présentée et soutenue publiquement par Jordana VIOTTO DA CRUZ Le 13 novembre 2017 « The Economics of Crowdfunding: Entrepreneurs’ and Platforms’ Strategies » Directeurs de thèse Marc BOURREAU, Télécom ParisTech François MOREAU, Université Paris 13 Jury Thierry PÉNARD, Professeur, Université Rennes 1 Président Paul BELLEFLAMME, Professeur, Aix-Marseille Université Rapporteur Jörg CLAUSSEN, Professeur, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Rapporteur Françoise BENHAMOU, Professeur, Université Paris 13 Examinateur Marc BOURREAU, Professeur, Télécom ParisTech Directeur de thèse François MOREAU, Professeur, Université Paris 13 Directeur de thèse UNIVERSITÉ PARIS 13 U.F.R. -

Ei-Report-2013.Pdf

Economic Impact United States 2013 Stavroulla Kokkinis, Athina Kohilas, Stella Koukides, Andrea Ploutis, Co-owners The Lucky Knot Alexandria,1 Virginia The web is working for American businesses. And Google is helping. Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful. Making it easy for businesses to find potential customers and for those customers to find what they’re looking for is an important part of that mission. Our tools help to connect business owners and customers, whether they’re around the corner or across the world from each other. Through our search and advertising programs, businesses find customers, publishers earn money from their online content and non-profits get donations and volunteers. These tools are how we make money, and they’re how millions of businesses do, too. This report details Google’s economic impact in the U.S., including state-by-state numbers of advertisers, publishers, and non-profits who use Google every day. It also includes stories of the real business owners behind those numbers. They are examples of businesses across the country that are using the web, and Google, to succeed online. Google was a small business when our mission was created. We are proud to share the tools that led to our success with other businesses that want to grow and thrive in this digital age. Sincerely, Jim Lecinski Vice President, Customer Solutions 2 Economic Impact | United States 2013 Nationwide Report Randy Gayner, Founder & Owner Glacier Guides West Glacier, Montana The web is working for American The Internet is where business is done businesses. -

The Top 10 Open Source Music Players Scores of Music Players Are Available in the Open Source World, and Each One Has Something That Is Unique

For U & Me Overview The Top 10 Open Source Music Players Scores of music players are available in the open source world, and each one has something that is unique. Here are the top 10 music players for you to check out. verybody likes to use a music player that is hassle- Amarok free and easy to operate, besides having plenty of Amarok is a part of the KDE project and is the default music Efeatures to enhance the music experience. The open player in Kubuntu. Mark Kretschmann started this project. source community has developed many music players. This The Amarok experience can be enhanced with custom scripts article lists the features of the ten best open source music or by using scripts contributed by other developers. players, which will help you to select the player most Its first release was on June 23, 2003. Amarok has been suited to your musical tastes. The article also helps those developed in C++ using Qt (the toolkit for cross-platform who wish to explore the features and capabilities of open application development). Its tagline, ‘Rediscover your source music players. Music’, is indeed true, considering its long list of features. 98 | FEBRUARY 2014 | OPEN SOURCE FOR YoU | www.LinuxForU.com Overview For U & Me Table 1: Features at a glance iPod sync Track info Smart/ Name/ Fade/ gapless and USB Radio and Remotely Last.fm Playback and lyrics dynamic Feature playback device podcasts controlled integration resume lookup playlist support Amarok Crossfade Both Yes Both Yes Both Yes Yes (Xine), Gapless (Gstreamer) aTunes Fade only -

"Licensing Music Works and Transaction Costs in Europe”

"Licensing music works and transaction costs in Europe” Final study September 2012 1 Acknowledgements: KEA would like to thank Google, the internet services company, for financing which made this study possible. The study was carried out independently and reflects the views of KEA alone. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Establishing and running online music services is a complex task, raising both technical and legal difficulties. This is particularly the case in Europe, where complex rights licensing structures hinder the development of the market and the launch of new innovative online services. Compared to the US, Europe is lagging behind in terms of digital music revenue. Furthermore, the development of the market is fairly disparate among different countries in the European Union. This study aims to identify and analyse transaction costs in music licensing. It examines the online music markets and outlines the licensing processes faced by online services. It offers a qualitative and quantitative analysis of transaction costs in the acquisition of the relevant rights by online music services. The study also suggests different ways of decreasing transaction costs. The research focuses on three countries (the UK, Spain and the Czech Republic) and builds on data collected through a survey with online music service providers available in the three countries as well as interviews with relevant stakeholders in the field of music licensing. THE EUROPEAN ONLINE MUSIC MARKET The music industry has steadily expanded over the past few years, away from selling CDs towards selling music online or through concerts and live music. (Masnick, Ho, 2012). Among the 500 licensed online music services in the world (according to IFPI), many emulate the physical record store, by offering ‘download to own’ tracks at a similar price point. -

REWARD-BASED CROWDFUNDING for CREATIVE PROJECTS by Aiste Juozaponyte 1548985 GRADUATION ASSIGNMENT SUBMITTED in PARTIAL FULFILLM

REWARD-BASED CROWDFUNDING FOR CREATIVE PROJECTS BY Aiste Juozaponyte 1548985 GRADUATION ASSIGNMENT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF COMMUNICATION- SYSTEMS OF THE INSTITUTE OF COMMUNICATION AT THE UTRECHT UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES UTRECHT, 2012 06 04 Management summary Crowdfunding is an emerging phenomenon that is taking the idea of investment into a new and never before seen level. Organizations and individuals find themselves achiev- ing successful results by relying on widely dispersed individuals rather than professional investors. The main aim of this thesis centers on potentials for non-professional creative individuals to use reward-based crowdfunding. The theoretical framework defines crowdfunding practice and gives an overview of how it emerged from another nascent term - crowdsourcing. Reward-based crowdfunding, as the focus of this study, is explained in greater detail by observing one of the most popular platforms for creative projects called Kickstarter. In addition, this chapter highlights that the crowd is playing a leading role in crowdfunding initiatives. Participating individuals are part of a community where conver- gence and collaboration take place. Furthermore, theory suggests that reward-based crowdfunding is not solely focused on economic aspects, as social attributes are shaping the scope of activities and goals. Conducted qualitative research confirms that several potentials are current for non- professional creative individuals to use reward-based crowdfunding model as researched on Kickstarter. Not only can they raise funding, but also gain significant public attention for their projects presented on Kickstarter. An appealing and transparent communication approach should be implemented, such as defining goals using S.M.A.R.T.