January, 1958

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountaineer December 2011

The Arizona Mountaineer December 2011 ORC students and instructors Day 3 - McDowell Mountains Photo by John Keedy The Arizona Mountaineering Club Meetings: The member meeting location is: BOARD OF DIRECTORS Granite Reef Senior Center President Bill Fallon 602-996-9790 1700 North Granite Reef Road Vice-President John Gray 480-363-3248 Scottsdale, Arizona 85257 Secretary Kim McClintic 480-213-2629 The meeting time is 7:00 to 9:00 PM. Treasurer Curtis Stone 602-370-0786 Check Calendar for date. Director-2 Eric Evans 602-218-3060 Director-2 Steve Crane 480-812-5447 Board Meetings: Board meetings are open to all members Director-1 Gretchen Hawkins 520-907-2916 and are held two Mondays prior to the Club meeting. Director-1 Bruce McHenry 602-952-1379 Director-1 Jutta Ulrich 602-738-9064 Dues: Dues cover January through December. A single membership is $30.00 per year: $35.00 for a family. COMMITTEES Those joining after June 30 pay $15 or $18. Members Archivist Jef Sloat 602-316-1899 joining after October 31 who pay for a full year will have Classification Nancy Birdwell 602-770-8326 dues credited through the end of the following year. Dues Elections John Keedy 623-412-1452 must be sent to: Equip. Rental Bruce McHenry 602-952-1379 AMC Membership Committee Email Curtis Stone 602-370-0786 6519 W. Aire Libre Ave. Land Advocacy Erik Filsinger 480-314-1089 Glendale, AZ 85306 Co-Chair John Keedy 623-412-1452 Librarian David McClintic 602-885-5194 Schools: The AMC conducts several rock climbing, Membership Rogil Schroeter 623-512-8465 mountaineering and other outdoor skills schools each Mountaineering Bruce McHenry 602-952-1379 year. -

Grand-Canyon-South-Rim-Map.Pdf

North Rim (see enlargement above) KAIBAB PLATEAU Point Imperial KAIBAB PLATEAU 8803ft Grama Point 2683 m Dragon Head North Rim Bright Angel Vista Encantada Point Sublime 7770 ft Point 7459 ft Tiyo Point Widforss Point Visitor Center 8480ft Confucius Temple 2368m 7900 ft 2585 m 2274 m 7766 ft Grand Canyon Lodge 7081 ft Shiva Temple 2367 m 2403 m Obi Point Chuar Butte Buddha Temple 6394ft Colorado River 2159 m 7570 ft 7928 ft Cape Solitude Little 2308m 7204 ft 2417 m Francois Matthes Point WALHALLA PLATEAU 1949m HINDU 2196 m 8020 ft 6144ft 2445 m 1873m AMPHITHEATER N Cape Final Temple of Osiris YO Temple of Ra Isis Temple N 7916ft From 6637 ft CA Temple Butte 6078 ft 7014 ft L 2413 m Lake 1853 m 2023 m 2138 m Hillers Butte GE Walhalla Overlook 5308ft Powell T N Brahma Temple 7998ft Jupiter Temple 1618m ri 5885 ft A ni T 7851ft Thor Temple ty H 2438 m 7081ft GR 1794 m G 2302 m 6741 ft ANIT I 2158 m E C R Cape Royal PALISADES OF GO r B Zoroaster Temple 2055m RG e k 7865 ft E Tower of Set e ee 7129 ft Venus Temple THE DESERT To k r C 2398 m 6257ft Lake 6026 ft Cheops Pyramid l 2173 m N Pha e Freya Castle Espejo Butte g O 1907 m Mead 1837m 5399 ft nto n m A Y t 7299 ft 1646m C N reek gh Sumner Butte Wotans Throne 2225m Apollo Temple i A Br OTTOMAN 5156 ft C 7633 ft 1572 m AMPHITHEATER 2327 m 2546 ft R E Cocopa Point 768 m T Angels Vishnu Temple Comanche Point M S Co TONTO PLATFOR 6800 ft Phantom Ranch Gate 7829 ft 7073ft lor 2073 m A ado O 2386 m 2156m R Yuma Point Riv Hopi ek er O e 6646 ft Z r Pima Mohave Point Maricopa C Krishna Shrine T -

Grand Canyon

ALT ALT To 389 To 389 To Jacob Lake, 89 To 89 K and South Rim a n a b Unpaved roads are impassable when wet. C Road closed r KAIBAB NATIONAL FOREST e in winter e K k L EA O N R O O B K NY O A E U C C N T E N C 67 I A H M N UT E Y SO N K O O A N House Rock Y N N A Buffalo Ranch B A KANAB PLATEAU C C E A L To St. George, Utah N B Y Kaibab Lodge R Mount Trumbull O A N KAIBAB M 8028ft De Motte C 2447m (USFS) O er GR C o Riv AN T PLATEAU K HUNDRED AND FIFTY MIL lorad ITE ap S NAVAJO E Co N eat C A s C Y RR C N O OW ree S k M INDIAN GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK B T Steamboat U Great Thumb Point Mountain C RESERVATION K 6749ft 7422ft U GREAT THUMB 2057m 2262m P Chikapanagi Point MESA C North Rim A 5889ft E N G Entrance Station 1795m M Y 1880ft FOSSIL R 8824ft O Mount Sinyala O U 573m G A k TUCKUP N 5434ft BAY Stanton Point e 2690m V re POINT 1656m 6311ft E U C SB T A C k 1924m I E e C N AT A e The Dome POINT A PL N r o L Y Holy Grail l 5486ft R EL Point Imperial C o Tuweep G W O Temple r 1672m PO N Nankoweap a p d H E o wea Mesa A L nko o V a Mooney D m N 6242ft A ID Mount Emma S Falls u 1903m U M n 7698ft i Havasu Falls h 2346m k TOROWEAP er C Navajo Falls GORGE S e v A Vista e i ITE r Kwagunt R VALLEY R N N Supai Falls A Encantada C iv o Y R nt Butte W d u e a O G g lor Supai 2159ft Unpaved roads are North Rim wa 6377ft r o N K h C Reservations required. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

Harvey Butchart's Hiking Log DETAILED HIKING LOGS (January

Harvey Butchart’s Hiking Log DETAILED HIKING LOGS (January 22, 1965 - September 25, 1965) Mile 24.6 and Hot Na Na Wash [January 22, 1965 to January 23, 1965] My guest for this trip, Norvel Johnson, thought we were going for just the day. When I told him it was a two day trip, he brought in his sleeping bag, but since he had no knapsack, we decided to sleep at the Jeep. The idea was to see Hot Na Na from the rim on Friday and then go down it as far as possible on Saturday. We thought we were following the Tanner Wash Quad map carefully when we left the highway a little to the north of the middle of the bay formed by Curve Wash in the Echo Cliffs. What we didn't realize is that there is another turnoff only a quarter of a mile north of the one we used. This is the way we came out of the hinterland on Saturday. Our exit is marked by a large pile of rocks and it gives a more direct access to all the country we were interested in seeing. The way we went in goes west, south, and north and we got thoroughly confused before we headed toward the rim of Marble Canyon. The track we followed goes considerably past the end of the road which we finally identified as the one that is one and a half miles north of Pine Reservoir. It ended near a dam. We entered the draw beyond the dam and after looking down at the Colorado River, decided that we were on the north side of the bay at Mile 24.6. -

Geographic Names

GEOGRAPHIC NAMES CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES ? REVISED TO JANUARY, 1911 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 PREPARED FOR USE IN THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE BY THE UNITED STATES GEOGRAPHIC BOARD WASHINGTON, D. C, JANUARY, 1911 ) CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES. The following list of geographic names includes all decisions on spelling rendered by the United States Geographic Board to and including December 7, 1910. Adopted forms are shown by bold-face type, rejected forms by italic, and revisions of previous decisions by an asterisk (*). Aalplaus ; see Alplaus. Acoma; township, McLeod County, Minn. Abagadasset; point, Kennebec River, Saga- (Not Aconia.) dahoc County, Me. (Not Abagadusset. AQores ; see Azores. Abatan; river, southwest part of Bohol, Acquasco; see Aquaseo. discharging into Maribojoc Bay. (Not Acquia; see Aquia. Abalan nor Abalon.) Acworth; railroad station and town, Cobb Aberjona; river, IVIiddlesex County, Mass. County, Ga. (Not Ackworth.) (Not Abbajona.) Adam; island, Chesapeake Bay, Dorchester Abino; point, in Canada, near east end of County, Md. (Not Adam's nor Adams.) Lake Erie. (Not Abineau nor Albino.) Adams; creek, Chatham County, Ga. (Not Aboite; railroad station, Allen County, Adams's.) Ind. (Not Aboit.) Adams; township. Warren County, Ind. AJjoo-shehr ; see Bushire. (Not J. Q. Adams.) Abookeer; AhouJcir; see Abukir. Adam's Creek; see Cunningham. Ahou Hamad; see Abu Hamed. Adams Fall; ledge in New Haven Harbor, Fall.) Abram ; creek in Grant and Mineral Coun- Conn. (Not Adam's ties, W. Va. (Not Abraham.) Adel; see Somali. Abram; see Shimmo. Adelina; town, Calvert County, Md. (Not Abruad ; see Riad. Adalina.) Absaroka; range of mountains in and near Aderhold; ferry over Chattahoochee River, Yellowstone National Park. -

Grand Canyon Archaeological Site

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE ETIQUETTE POLICY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE ETIQUETTE POLICY For Colorado River Commercial Operators This etiquette policy was developed as a preservation tool to protect archaeological sites along the Colorado River. This policy classifies all known archaeological sites into one of four classes and helps direct visitors to sites that can withstand visitation and to minimize impacts to those that cannot. Commercially guided groups may visit Class I and Class II sites; however, inappropriate behaviors and activities on any archaeological site is a violation of federal law and Commercial Operating Requirements. Class III sites are not appropriate for visitation. National Park Service employees and Commercial Operators are prohibited from disclosing the location and nature of Class III archaeological sites. If clients encounter archaeological sites in the backcountry, guides should take the opportunity to talk about ancestral use of the Canyon, discuss the challenges faced in protecting archaeological resources in remote places, and reaffirm Leave No Trace practices. These include observing from afar, discouraging clients from collecting site coordinates and posting photographs and maps with location descriptions on social media. Class IV archaeological sites are closed to visitation; they are listed on Page 2 of this document. Commercial guides may share the list of Class I, Class II and Class IV sites with clients. It is the responsibility of individual Commercial Operators to disseminate site etiquette information to all company employees and to ensure that their guides are teaching this information to all clients prior to visiting archaeological sites. Class I Archaeological Sites: Class I sites have been Class II Archaeological Sites: Class II sites are more managed specifically to withstand greater volumes of vulnerable to visitor impacts than Class I sites. -

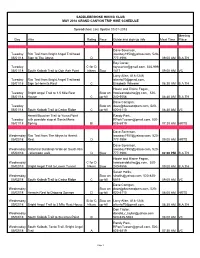

Day Hike Rating Pace Guide and Sign-Up Info Meet Time Meeting

SADDLEBROOKE HIKING CLUB MAY 2018 GRAND CANYON TRIP HIKE SCHEDULE Spreadsheet Last Update 03-01-2018 Meeting Day Hike Rating Pace Guide and sign-up info Meet Time Place Dave Sorenson, Tuesday Rim Trail from Bright Angel Trailhead [email protected], 520- 05/01/18 Sign to The Abyss D 777-1994 09:00 AM B.A.TH Roy Carter, Tuesday C for D [email protected], 520-999- 05/01/18 South Kaibab Trail to Ooh Aah Point hikers Slow 1417 09:00 AM VC Larry Allen, 818-1246, Tuesday Rim Trail from Bright Angel Trailhead [email protected], 05/01/18 Sign to Hermits Rest C Elisabeth Wheeler 08:30 AM B.A.TH Howie and Elaine Fagan, Tuesday Bright Angel Trail to 1.5 Mile Rest Slow on [email protected], 520- 05/01/18 House C up-hill 240-9556 08:30 AM B.A.TH Dave Corrigan, Tuesday Slow on [email protected], 520- 05/01/18 South Kaibab Trail to Cedar Ridge C up-hill 820-6110 08:30 AM VC Hermit/Boucher Trail to Yuma Point Randy Park, Tuesday with possible stop at Santa Maria [email protected], 520- 05/01/18 Spring B! 825-6819 07:30 AM HRTS Dave Sorenson, Wednesday Rim Trail from The Abyss to Hermit [email protected], 520- 05/02/18 Rest D 777-1994 09:00 AM HRTS Dave Sorenson, Wednesday Historical Buildings Walk on South Rim [email protected], 520- 05/02/18 - afternoon walk D Slow 777-1994 02:00 PM B.A.TH Howie and Elaine Fagan, Wednesday C for D [email protected], 520- 05/02/18 Bright Angel Trail to Lower Tunnel hikers Slow 240-9556 09:00 AM B.A.TH Susan Hollis, Wednesday Slow on [email protected], 520-825- 05/02/18 South Kaibab Trail -

Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Page Title South Rim: May 24–September 7, 2009 Also Available in Deutsch, Español, Français, the Guide Italiano,

SPRING 2008 VISITOR’S GUIDE 1 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Page Title South Rim: May 24–September 7, 2009 Also available in Deutsch, Español, Français, The Guide Italiano, , NPS photo by Michael Quinn Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park Construction Ahead! Drive Cautiously. Look inside for The Grand Canyon we visit today is a gift from past generations. Take time to Road construction in the Mather Point – Canyon View Information Plaza area information on: enjoy this gift. Sit and watch the changing play of light and shadows. Wander continues throughout the summer. When the project is completed this fall, the Maps ............10–11,17,20 along a trail and feel the sunshine and wind on your face. Follow the antics of road will skirt the south side of Canyon View Information Plaza and additional Ranger Programs...........2–4 the ravens soaring above the rim. Can you hear the river roaring in the gorge far parking will provide easy access to the visitor center and rim. See additional below? We must ensure that future generations have the opportunity to form information on this project on page 9. Information Centers ......... 7 connections with this inspiring landscape. Drive slowly and obey all construction zone signs and flaggers. Sunrise & Sunset Times ....... 7 A few suggestions may make your visit more rewarding. The information in this Geology ................... 8 publication will answer many of your questions about the South Rim. Stop by Stop in One of the Visitor Centers Hiking..................16–17 a visitor center and talk with a ranger. -

Grand Canyon Guide

National Park Service Grand Canyon U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Arizona South Rim: March 1–May 24, 2008 Also available in Deutsch, Espan˜ ol, Français, The Guide Italiano, , Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park The Grand Canyon is more than a great chasm carved over millennia through along a trail and feel the sunshine and wind on your face. Attend a ranger the rocks of the Colorado Plateau. It is more than an awe-inspiring view. It is program. Follow the antics of ravens soaring above the rim. Listen for the more than a pleasuring ground for those who explore the roads, hike the roar of the rapids far below Pima Point. Savor a sunrise or sunset. trails, or float the currents of the turbulent Colorado River. As the shadows lengthen across the spires and buttes, time passing into the This canyon is a gift that transcends what we experience. Its beauty and size depths of the canyon, understand what this great chasm passes to us—a sense humble us. Its timelessness provokes a comparison to our short existence. of humility born in the interconnections of all that is and a willingness to care South Rim Map on Its vast spaces offer solace from our hectic lives. for this land. We have the responsibility to ensure that future generations pages 8–9 and 16 have the opportunity to form their own connections with Grand Canyon The Grand Canyon we visit today is a gift from past generations. Take time to National Park. enjoy this gift. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8/86) NPS/WHS Word Processor Format (Approved 03/88) United States Department of the Interior NationaL Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibiLity for individual properties or districts. See instructions in GuideLines for CompLeting NationaL Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). CompLete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materiaLs, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories Listed in the instructions. For additionaL space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type aLL entries. Use Letter QuaLity printers in 12 pitch. Use onLy 25% or greater cotton content bond paper. 1. Name of Property historic name Hermit TraiL other names/site number Santa Maria TraiL 2. Location street & number Grand Canyon NationaL Park city, town Grand Canyon X vicinity state Arizona code AZ county Coconino code 005 zip code 86023 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property No. of Resources within Property private buiLding(s) contributing noncontributing public-Local district 3 1 buiLdings public-State site 1 3 sites X public-FederaL X structure 1 3 structures object 4 objects 5 11 TotaL Name of related multiple property listing: No. of contributing resources previousLy Historic Roads and TraiLs of Grand Canyon, Arizona listed in the National Register N/A USDI/NPS NRHP Property Documentation Form 2 Hermit Trail, Coconino County, Arizona 4. -

Colorado River Management Plan, 2019 Commercial Operating

2019 CORs COMMERCIAL OPERATING REQUIREMENTS PAGE 1 ATTACHMENT 1 COLORADO RIVER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2019 COMMERCIAL OPERATING REQUIREMENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I. WATERCRAFT AND CAPACITIES ............................................................................... 4 A. Types of Watercraft................................................................................................ 4 B. Capacities .............................................................................................................. 4 C. Individual Watercraft ............................................................................................. 5 D. Registration ............................................................................................................ 5 E. Name and Logo ...................................................................................................... 5 F. Best Management Practices ................................................................................... 6 II. EMERGENCY EQUIPMENT AND PROCEDURES ...................................................... 6 A. Personal Flotation Devices (PFDs) ........................................................................ 6 B. Navigation Light .................................................................................................... 6 C. Incident Response .................................................................................................. 6 D. First Aid ................................................................................................................