Alfred Jensen : Paintings and Works on Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adolf Fleischmann (1892—1968)

ADOLF FLEISCHMANN (1892—1968) snoeck ADOLF FLEISCHMANN An American Abstract Artist? Themen, Kontext und Rezeption des US-amerikanischen Spätwerks 1952 bis 1967 Themes, Context and Reception of Fleischmann’s late American period 1952 to 1967 Herausgegeben von / Edited by Renate Wiehager für die / for the Daimler Art Collection D AC Vorwort 7 Preface 11 RENATE WIEHAGER Adolf Fleischmann. An American Abstract Artist? Themen, Kontext und Rezeption des amerikanischen Spätwerks 1952–1967 15 Themes, Context and Reception of Fleischmann’s Late American Period 1952–1967 39 Historische Texte zum Spätwerk 1952–1976 86 Historical Texts on the Late Period 1952–1976 177 JULIAN ALVARD / R.V. GINDERTAEL [1952] 86/177 MICHEL SEUPHOR [1952] 89/180 DARIO SURO [1955] 90/181 DARIO SURO [1956] 94/184 BENEDICT FRED DOLBIN [1957] 96/187 SANSON FLEXOR [1957] 98/188 MICHEL SEUPHOR [1959] 119/189 RAYMOND BAYER [1964] 120/190 KURT LEONHARD [1967] 130/196 ALBERT SCHULZE VELLINGHAUSEN [1967] 135/199 CARLO BELLOLI [1970] 136/201 EUGEN GOMRINGER [1971] 139/205 EUGEN GOMRINGER [1972] 141/206 MICHEL SEUPHOR [1976] 145/208 THOMAS SCHNALKE Anatomie in Bewegung. Annäherungen an den medizinischen Illustrator und abstrakten Künstler Adolf Fleischmann 163 Anatomy in Motion. Some Remarks on the Medical Illustrator and Abstract Artist Adolf Fleischmann 169 Biografie/Biography 213/220 Einzelausstellungen/Solo Exhibitions 254 Gruppenausstellungen/Group Exhibitions 255 Werke in öffentlichen Sammlungen/Works in Public Collections 263 Literaturverzeichnis/Bibliography 266 Impressum/Imprint 280 VORWORT Adolf Fleischmann (1892–1968), mit einer bedeutenden Werkgruppe in der Daimler Art Collection vertreten, ist einer der herausragenden abstrakten Maler in Deutsch- land und den USA nach 1945. -

Hans Hofmann (German-American Painter, 1880-1966)

237 East Palace Avenue Santa Fe, NM 87501 800 879-8898 505 989-9888 505 989-9889 Fax [email protected] Hans Hofmann (German-American Painter, 1880-1966) Hans Hofmann is one of the most important figures of postwar American art. Celebrated for his exuBerant, color-filled canvases, and renowned as an influential teacher for generations of artists— first in his native Germany, then in New York and Provincetown—Hofmann played a pivotal role in the development of ABstract Expressionism. As a teacher he Brought to America direct knowledge of the work of a celebrated group of European modernists (prior to World War I he had lived and studied in Paris) and developed his own philosophy of art, which he expressed in essays which are among the most engaging discussions of painting in the twentieth century, including "The Color ProBlem in Pure Painting—Its Creative Origin." Hofmann taught art for over four decades; his impressive list of students includes Helen Frankenthaler, Red Grooms, Alfred Jensen, Wolf Kahn, Lee Krasner, Louise Nevelson and Frank Stella. As an artist Hofmann tirelessly explored pictorial structure, spatial tensions and color relationships. In his earliest portraits done just years into the twentieth century, his interior scenes of the 1940s and his signature canvases of the late 1950s and the early 1960s, Hofmann brought to his paintings what art historian Karen Wilkin has descriBed as a "range from loose accumulations of Brushy strokes…to crisply tailored arrangements of rectangles…But that somehow seems less significant than their uniform intensity, their common pounding energy and their consistent physicality." Hofmann was Born Johann Georg Hofmann in WeissenBerg, in the Bavarian state of Germany in 1880 and raised and educated in Munich. -

Exhibition Brochure, Alfred Jensen, Concordance.Pdf

Alfred Jensen Concordance September 20, 2001-June 16, 2002 site map and checklist Born in 1903 in Guatemala City, Alfred Jensen studied fine art in San Diego ( ( (1924-1925), Munich (1926-1927), and Paris (1929). After traveling extensively 14 throughout Europe and northern Africa, Jensen took up residency in New York in the early 1950s, after which he devoted himself to painting full time. He exhibited widely 7. Das Bild der Sonne: The Square's Duality, following his first solo show at John Heller Gallery in New York in 1952. Among 13 Progression and Growth, and Squaring the 360 Day Calendar, 1 966 numerous group exhibitions, he was included in the Venice Biennial (1964), oil on canvas Documenta IV (1968) and Documenta V (1972), the Whitney Biennial (1973, 1977), 7 110 84 x 336 inches 12 Collection of Michael and Judy Ovitz, the Sii.o Paulo Biennial (1977), and "Bilderstreit" (1989). One-person exhibitions Los Angeles included venues such as the Guggenheim Museum, New York ( 1961 ), Stedelijk 8. The Sun Rises Twice, Per I-Per IV, 1 973 Museum, Amsterdam (1964), Kunsthalle Basel (1975), and the Newark Art Museum 11 oil on canvas (1994). Traveling retrospective tours were organized in 1973 by the Kestner 96 x 192 inches Collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and Gesellschaft, Hannover (traveled to Humlebaek, Baden-Baden, Dusseldorf, and Bern), Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington. Joseph H. Hirshhorn Purchase and in 1978 by the Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo (traveled to New York, Chicago, La Fund, 1990. Jolla, Boulder, and San Francisco). Four years after Jensen's death in 1981, the 9. -

Oral History Interview with Clark Richert, 2013 August 20-21

Oral history interview with Clark Richert, 2013 August 20-21 Funding for this interview was provided by the Stoddard-Fleischman Fund for the History of Rocky Mountain Area Artists. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Clark Richert on August 20-21, 2013. The interview took place in Denver, Colo., and was conducted by Elissa Auther for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Stoddard-Fleischman History of Rocky Mountain Area Artists project. [Narrator] and the [Interviewer] have reviewed the transcript. Their corrections and emendations appear below in brackets appended by initials. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ELISSA AUTHER: This is Elissa Auther interviewing Clark Richert at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver, on August 20th, for the Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art, card one. Clark, when did you decide to become an artist and what led up to that decision? CLARK RICHERT: I think I know almost the exact moment when I decided to become an artist. I was living in Wichita, Kansas, going to high school, Wichita East High, and was at a local bookstore perusing the books and I saw this book on the shelf that really puzzled me. The name of it was the Dictionary of Abstract Art. And I opened up the book and flipped through the pages, and I came to this painting by Rothko which really puzzled me. -

New York State Office of General Services Art Conservation and Restoration Services – Solicitation Number 1444

Request for Proposals (RFP) are being solicited by the New York State Office of General Services For Art Conservation and Restoration Services January 29, 2009 Class Codes: 82 Group Number: 80107 Solicitation Number: 1444 Contract Period: Three years with Two One-Year Renewal Options Proposals Due: Thursday, March 12, 2009 Designated Contact: Beth S. Maus, Purchasing Officer NYS Office of General Services Corning Tower, 40th Floor Empire State Plaza Albany, New York 12242 Voice: 1-518-474-5981 Fax: 1-518-473-2844 Email: [email protected] New York State Office of General Services Art Conservation and Restoration Services – Solicitation Number 1444 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Designated Contact..................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Minimum Bidder Qualifications.................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Pre-Bid Conference..................................................................................................................... 5 1.5 Key Events .................................................................................................................................. 5 2. PROPOSAL SUBMISSION......................................................................................................... -

Download Exhibition Catalogue

LIGHT / SPACE / CODE Opposite: Morris Louis, Number 2-07, 1961 (detail) Light / Space / Code How Real and Virtual Systems Intersect The Light and Space movement (originated in the 1960s) coincided with the Visual art and the natural sciences have long produced fruitful collaborations. development of digital technology and modern computer programming, and in Even Isaac Newton’s invention of the color wheel (of visible light spectra) has recent years artists have adapted hi-tech processes in greater pursuit of altering aided visual artists immensely. Artists and scientists share a likeminded inquiry: a viewer’s perception using subtle or profound shifts in color, scale, luminosity how we see. Today’s art answers that question in tandem with the expanded and spatial illusion. scientific fields of computer engineering, cybernetics, digital imaging, information processing and photonics. Light / Space / Code reveals the evolution of Light and Space art in the context of emerging technologies over the past half century. The exhibit begins by iden- — Jason Foumberg, Thoma Foundation curator tifying pre-digital methods of systems-style thinking in the work of geometric and Op painters, when radiant pigments and hypnotic compositions inferred the pow- er of light. Then, light sculpture introduces the medium of light as an expression of electronic tools. Finally, software-generated visualizations highlight advanced work in spatial imaging and cyberspace animation. Several kinetic and inter- active works extend the reach of art into the real space of viewer participation. A key sub-plot of Light / Space / Code concerns the natural world and its ecol- ogy. Since the Light and Space movement is an outgrowth of a larger environ- mental art movement (i.e., Earthworks), and its materials are directly drawn from natural phenomena, Light and Space artists address the contemporary conditions of organisms and their habitation systems on this planet. -

Sol Lewitt Biography

SOL LEWITT BIOGRAPHY BORN 1928-2007, Hartford, CT SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 By Hand: Sol LeWitt; The Mattatuck Museum; Waterbury, CT Sol LeWitt Wall Drawings: Expanding a Legacy; Yale University Art Gallery; New Haven, CT Sol LeWitt: Between the Lines; Fondazione Carriero; Milan, Italy Sol LeWitt: Progression Towers ; Miami Design District & Institute of Contemporary Art; Miami, FL Sol LeWitt; Honor Fraser; Los Angeles, CA Sol LeWitt: 1 + 1 = 1 Million; Vito Schnabel Gallery; St. Moritz, Switzerland Sol LeWitt: Large Gouaches; Paula Cooper Gallery; New York, NY 2016 Sol LeWitt; Paula Cooper Gallery; New York, NY Sol LeWitt; Cardi Gallery; Milan, Italy Sol LeWitt: Seven Weeks, Seven Wall Drawings; Barbara Krakow Gallery; Boston, MA 2015 Soll LeWitt in Connecticut; James Barron; Kent, CT Sol LeWitt: 17 Wall Drawings 1970-2015; Fundacion Botin; Santander, Spain Sol LeWitt; Noire Gallery; Cappella del Brichetto, San Sebastiano, Italy Sol LeWitt: Wall Drawings, Grids on Color; Konrad Fischer Galerie; Dusseldorf, Germany Sol LeWitt: Wall Drawings, Grids on Black and White; Konrad Fischer Galerie; Berlin, Germany Sol LeWitt: Structures & Related Works on Paper 1968-2005; Barbara Krakow Gallery; Boston, MA Sol LeWitt: 40 Years at Annemarie Verna Gallery Part I; Annemarie Verna; Zurich, Switzerland Sol LeWitt; GalerÃa Elvira González; Madrid, Spain 2014 Sol LeWitt: Creating Place; Asheville Art Museum; Asheville, NC Sol LeWitt: Wall Drawing #370; The Metropolitan Museum of Art; New York, NY Sol LeWitt: Your Mind is Exactly at that Line; Art Gallery of New South Wales; Sydney, Australia Sol LeWitt: Prints; Pace Prints; New York, NY Sol LeWitt: Horizontal Progressions; Pace Gallery; New York, NY 2013 Sol LeWitt: Cut Torn Folded Ripped; James Cohan Gallery; New York, NY Sol LeWitt: Shaping Ideas; Laurie M. -

Ars Libri Ltd Modernart

MODERNART ARS LIBRI LT D 149 C ATALOGUE 159 MODERN ART ars libri ltd ARS LIBRI LTD 500 Harrison Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02118 U.S.A. tel: 617.357.5212 fax: 617.338.5763 email: [email protected] http://www.arslibri.com All items are in good antiquarian condition, unless otherwise described. All prices are net. Massachusetts residents should add 6.25% sales tax. Reserved items will be held for two weeks pending receipt of payment or formal orders. Orders from individuals unknown to us must be accompanied by pay- ment or by satisfactory references. All items may be returned, if returned within two weeks in the same con- dition as sent, and if packed, shipped and insured as received. When ordering from this catalogue please refer to Catalogue Number One Hundred and Fifty-Nine and indicate the item number(s). Overseas clients must remit in U.S. dollar funds, payable on a U.S. bank, or transfer the amount due directly to the account of Ars Libri Ltd., Cambridge Trust Company, 1336 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02238, Account No. 39-665-6-01. Mastercard, Visa and American Express accepted. June 2011 avant-garde 5 1 AL PUBLICO DE LA AMERICA LATINA, y del mondo entero, principalmente a los escritores, artistas y hombres de ciencia, hacemos la siguiente declaración.... Broadside poster, printed in black on lightweight pale peach-pink translucent stock (verso blank). 447 x 322 mm. (17 5/8 x 12 3/4 inches). Manifesto, dated México, sábado 18 de junio de 1938, subscribed by 36 signers, including Manuel Alvárez Bravo, Luis Barragán, Carlos Chávez, Anto- nio Hidalgo, Frieda [sic] Kahlo, Carlos Mérida, César Moro, Carlos Pellicer, Diego Rivera, Rufino Tamayo, Frances Toor, and Javier Villarrutia. -

Annual Report 2013

N A TIO NAL G ALL E R Y O F A R T 2013 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION Louise Bryson BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEE Vincent J. Buonanno (as of 30 September 2013) Victoria P. Sant W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Chairman Calvin Cafritz Earl A. Powell III Louisa Duemling Frederick W. Beinecke Barney A. Ebsworth Mitchell P. Rales Gregory W. Fazakerley Sharon P. Rockefeller Doris Fisher Andrew M. Saul Aaron I. Fleischman Marina Kellen French FINANCE COMMITTEE Morton Funger Mitchell P. Rales Rose Ellen Greene Chairman Frederic C. Hamilton Jacob J. Lew Teresa Heinz Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin R. Jacobs Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Victoria P. Sant Betsy K. Karel Sharon P. Rockefeller Chairman President Linda H. Kaufman Victoria P. Sant Mark J. Kington Andrew M. Saul Robert L. Kirk Jo Carole Lauder AUDIT COMMITTEE Leonard A. Lauder Frederick W. Beinecke LaSalle D. Leffall Jr. Chairman Edward J. Mathias Mitchell P. Rales Robert B. Menschel Sharon P. Rockefeller Diane A. Nixon Victoria P. Sant Tony Podesta Andrew M. Saul Frederick W. Beinecke Mitchell P. Rales Diana C. Prince Robert M. Rosenthal TRUSTEES EMERITI Roger W. Sant Robert F. Erburu B. Francis Saul II Julian Ganz, Jr. Fern M. Schad Alexander M. Laughlin Michelle Smith David O. Maxwell Luther M. Stovall John Wilmerding Ladislaus von Hoffmann Christopher V. Walker EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Diana Walker Victoria P. Sant Alice L. Walton President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Walter L. Weisman Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III Director Andrea Woodner United States Franklin Kelly Deputy Director and HONORARY TRUSTEES’ Chief Curator COUNCIL William W. -

Lot 3470 A189 Postwar & Contemporary

Koller Auktionen - Lot 3470 A189 PostWar & Contemporary - samedi 29 juin 2019, 14h00 HANS HOFMANN (Weissenburg/Bavaria 1888 - 1966 New York) The Tree. 1944. Oil and gouache on wove paper (double sided). Signed lower right: Hans Hofmann. 73.5 x 58.5 cm. Provenienz : - André Emmerich, New York, Art Basel. - Purchased from the above at Art Basel by the present owner, since then private collection Switzerland. “Abstract Expressionism was and is just as European, since it was born in Munich.” Michel Seuphor Hans Hofmann was born Johann Georg Albert Hofmann on 21 March 1888, in Weissenburg Bavaria, the second of five children. Little is known about his artistic talent as a child. With the move to Munich, where his father worked Koller Auctions, Hardturmstrasse 102, 8031 Zürich. Tel +41 44 445 63 63. [email protected] Koller Auktionen - Lot 3470 A189 PostWar & Contemporary - samedi 29 juin 2019, 14h00 as a civil servant in the Bavarian Ministry of the Interior, the young Hans Hofmann arrived in the most important city after Paris for the avant-garde before the First World War. It is here where his education began, shaped by the city’s unbelievable art collections and the emerging modern art, represented by the founding of the artist group “The Blue Rider”. Soon the Berlin art dealer Bruno Cassirer became aware of Hofmann’s work and provided him with the financial support of Philipp Freudenberg, whereby it was possible for the young artist to go to Paris in 1904 and to live there for 10 years. There he immersed himself fully in the art scene, got to know the artists of the avant-garde, made friends with Robert Delaunay amongst others and met the German dealers Richard Goetz and Wilhelm Uhde. -

For Two-Dimensional Art Conservation

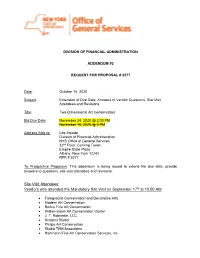

DIVISION OF FINANCIAL ADMINISTRATION ADDENDUM #2 REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL # 2277 Date: October 16, 2020 Subject: Extension of Due Date, Answers to Vendor Questions, Site Visit Attendees and Revisions Title: Two-Dimensional Art Conservation Bid Due Date: November 24, 2020 @ 2:00 PM November 10, 2020 @ 2 PM Address Bids to: Lee Amado Division of Financial Administration NYS Office of General Services 32nd Floor, Corning Tower Empire State Plaza Albany, New York 12242 RFP # 2277 To Prospective Proposers: This addendum is being issued to extend the due date, provide answers to questions, site visit attendees and revisions. Site Visit Attendees: Vendors who attended the Mandatory Site Visit on September 17th at 10:00 AM • Foreground Conservation and Decorative Arts • Modern Art Conservation • Burica Fine Art Conservation • Williamstown Art Conservation Center • J. T. Robinette, LLC • Scarpini Studio • Philips Art Conservation • Studio TKM Associates • Hartmann Fine Art Conservation Services, Inc. RFP 2277- Two-Dimensional Art Conservation • Fine Art Conservation Group • Athena Art Conservation • Gianfranco Pocobene Studio Questions and Answers: Answers to Questions submitted by Vendors who attended the Mandatory Site Visit on September 17 at 10:00am Exhibit 1- Lot 1 Q1. Exhibit 1 – Lot 1- Governor Nelson A Rockefeller Empire State Plaza Art Collection/Harlem Collection. The location designation indicates OGS Storage as well as conservation. a. Can you please clarify and describe how these are stored ( ie. in flat file drawers) and if they are all in one location for the required examinations? b. Specifically I am wondering how burdensome the access for each piece is, are they within folders or are most framed? c. -

John Allan Walker Art Catalog Collection SPC.2007.007

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c82b953d No online items Inventory of the John Allan Walker Art Catalog Collection SPC.2007.007 Greg Williams California State University Dominguez Hills, Gerth Archives and Special Collections 2011 University Library South -5039 (Fifth Floor) 1000 E. Victoria St. Carson, CA 90747 [email protected] URL: https://www.csudh.edu/libarchives/ Inventory of the John Allan SPC.2007.007 1 Walker Art Catalog Collection SPC.2007.007 Contributing Institution: California State University Dominguez Hills, Gerth Archives and Special Collections Title: John Allan Walker Art Catalog Collection Creator: Walker, John Allan Identifier/Call Number: SPC.2007.007 Physical Description: 186 boxes Physical Description: 59 Linear Feet Date (inclusive): 1882-2002 Date (bulk): 1919-2002 Abstract: This collection consists of art catalogs from museums, galleries, and other entities. first floor storage Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access There are no access restrictions on this collection. Conditions Governing Use All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Director of Archives and Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical materials and not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained. Preferred Citation [title of item] John Allan Walker Art Catalog Collection, Courtesy of the Gerth Archives and Special Collections. University Library. California State University, Dominguez Hills Scope and Contents The John Allan Walker Art Catalog Collection (1882-2002; bulk 1919-2002) consists of exhibition catalogs for art galleries, museums and other entities collected by John Allan Walker.