Jewish Ideas of God

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Invention Of

How Did God Get Started? COLIN WELLS the usual suspects One day in the Middle East about four thousand years ago, an elderly but still rather astonishingly spry gentleman took his son for a walk up a hill. The young man carried on his back some wood that his father had told him they would use at the top to make an altar, upon which they would then perform the ritual sacrifice of a burnt offering. Unbeknownst to the son, however, the father had another sort of sacrifice in mind altogether. Abraham, the father, had been commanded, by the God he worshipped as supreme above all others, to sacrifice the young man himself, his beloved and only legitimate son, Isaac. We all know how things turned out, of course. An angel appeared, together with a ram, letting Abraham know that God didn’t really want him to kill his son, that he should sacrifice the ram instead, and that the whole thing had merely been a test. And to modern observers, at least, it’s abundantly clear what exactly was being tested. Should we pose the question to most people familiar with one of the three “Abrahamic” religious traditions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam), all of which trace their origins to this misty figure, and which together claim half the world’s population, the answer would come without hesitation. God was testing Abraham’s faith. If we could ask someone from a much earlier time, however, a time closer to that of Abraham himself, the answer might be different. The usual story we tell ourselves about faith and reason says that faith was invented by the ancient Jews, whose monotheistic tradition goes back to Abraham. -

'Come': Apologetics and the Witness of the Holy Spirit

1 THE SPIRIT AND THE BRIDE SAY ‘COME’: APOLOGETICS AND THE WITNESS OF THE HOLY SPIRIT Kevin Kinghorn and Jerry L. Walls In a word, Christian apologetics is a defense of Christian theism. The Greek word apologia may refer to the kind of reasoned case a lawyer provides in defending the innocence of an accused person. Or, more broadly, the word may refer to any line of argument showing the truth of some position. 1 Peter 3:15 contains the instruction to Christians: “Always be prepared to give an answer [apologia] to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have.”1 1. Testimony: human and divine Within the four Gospels one finds a heavy emphasis on human testimony in helping others come to beliefs about Christ. For example, St. Luke opens his Gospel by explaining to its recipient, Theophilus, that he is writing “an orderly account” of the life of Jesus “so that you may know the certainty of the things you have been taught.” Luke describes himself as drawing together a written account of things “just as they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses and servants of the Word.”2 As Richard Swinburne remarks, “it is hard to read the Gospels, Acts of the Apostles, and 1 Corinthians without seeing them as claiming that various historical events (above all, the Resurrection) occurred and that others can know these things on the testimony of the apostles to have seen them.”3 This passing down of apostolic testimony continued through the next generations of the early Christian Church. -

Adonai & Elohim

Adonai (Adonay) & Elohim/El/Eloah & / / אלה אל אלוהים אֲדֹנָי Except for "YHWH", the two most common names/titles for GOD in the Biblia Hebraica (Hebrew Bible) are "Adonai" and "Elohim". Apart from the name "YHWH", the designations "Adonai" and "Elohim" say more about the GOD of Israel than any other name. Certainly, all that the names embody deserve considerable deliberation. Because the two words are so similar to each other and are often combined in the Old Testament, I thought it logical to study these two names together. Etymology -mean ,(" אָדֹן") (Adonai: "Adonai " derives from the Hebrew root "adon " (pronounced 'âdôn ing master , owner , or sovereign ruler . Thus, when referring to the GOD of Israel, the name expresses the authority and the exalted position of GOD. In the ordinary sense, "adon " refers to both human and divine relationships. The word "adon " (plural "adonai") appears ±335 times throughout Scripture, frequently in reference to a servant’s master or the family patriarch. So Sarah laughed to herself as she thought, "After I am worn out and my lord (adon) is old, will I now have this pleasure?" (Genesis 18:12 parenthetical text added ) "My lords (adonai) ," he said, "please turn aside to your servant's house. You can wash your feet and spend the night and then go on your way early in the morning." (Genesis 19:2a parenthetical text added ) The angel answered me, "These are the four spirits of heaven, going out from standing in the presence of the Lord (Adon) of the whole world. (Zechariah 6:5 parenthetical text added ) is the emphatic plural form of "adon" and is used exclusively as a (" אֲדֹנָי") "The name "Adonai proper name of God. -

Kant's Theoretical Conception Of

KANT’S THEORETICAL CONCEPTION OF GOD Yaron Noam Hoffer Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Philosophy, September 2017 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________________ Allen W. Wood, Ph.D. (Chair) _________________________________________ Sandra L. Shapshay, Ph.D. _________________________________________ Timothy O'Connor, Ph.D. _________________________________________ Michel Chaouli, Ph.D 15 September, 2017 ii Copyright © 2017 Yaron Noam Hoffer iii To Mor, who let me make her ends mine and made my ends hers iv Acknowledgments God has never been an important part of my life, growing up in a secular environment. Ironically, only through Kant, the ‘all-destroyer’ of rational theology and champion of enlightenment, I developed an interest in God. I was drawn to Kant’s philosophy since the beginning of my undergraduate studies, thinking that he got something right in many topics, or at least introduced fruitful ways of dealing with them. Early in my Graduate studies I was struck by Kant’s moral argument justifying belief in God’s existence. While I can’t say I was convinced, it somehow resonated with my cautious but inextricable optimism. My appreciation for this argument led me to have a closer look at Kant’s discussion of rational theology and especially his pre-critical writings. From there it was a short step to rediscover early modern metaphysics in general and embark upon the current project. This journey could not have been completed without the intellectual, emotional, and material support I was very fortunate to receive from my teachers, colleagues, friends, and family. -

The Suppression of Jewish Culture by the Soviet Union's Emigration

\\server05\productn\B\BIN\23-1\BIN104.txt unknown Seq: 1 18-JUL-05 11:26 A STRUGGLE TO PRESERVE ETHNIC IDENTITY: THE SUPPRESSION OF JEWISH CULTURE BY THE SOVIET UNION’S EMIGRATION POLICY BETWEEN 1945-1985 I. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL STATUS OF JEWS IN THE SOVIET SOCIETY BEFORE AND AFTER THE WAR .................. 159 R II. BEFORE THE BORDERS WERE CLOSED: SOVIET EMIGRATION POLICY UNDER STALIN (1945-1947) ......... 163 R III. CLOSING OF THE BORDER: CESSATION OF JEWISH EMIGRATION UNDER STALIN’S REGIME .................... 166 R IV. THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES: SOVIET EMIGRATION POLICY UNDER KHRUSHCHEV AND BREZHNEV .................... 168 R V. CONCLUSION .............................................. 174 R I. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL STATUS OF JEWS IN THE SOVIET SOCIETY BEFORE AND AFTER THE WAR Despite undergoing numerous revisions, neither the Soviet Constitu- tion nor the Soviet Criminal Code ever adopted any laws or regulations that openly or implicitly permitted persecution of or discrimination against members of any minority group.1 On the surface, the laws were always structured to promote and protect equality of rights and status for more than one hundred different ethnic groups. Since November 15, 1917, a resolution issued by the Second All-Russia Congress of the Sovi- ets called for the “revoking of all and every national and national-relig- ious privilege and restriction.”2 The Congress also expressly recognized “the right of the peoples of Russia to free self-determination up to seces- sion and the formation of an independent state.” Identical resolutions were later adopted by each of the 15 Soviet Republics. Furthermore, Article 124 of the 1936 (Stalin-revised) Constitution stated that “[f]reedom of religious worship and freedom of anti-religious propaganda is recognized for all citizens.” 3 1 See generally W.E. -

APA Newsletters

APA Newsletters Volume 02, Number 1 Fall 2002 NEWSLETTER ON PHILOSOPHY AND THE BLACK EXPERIENCE LETTER FROM THE NEW EDITORS, JOHN MCCLENDON & GEORGE YANCY ARTICLES JOHN H. MCCLENDON III “Black and White contra Left and Right? The Dialectics of Ideological Critique in African American Studies” GEORGE YANCY “Black Women’s Experiences, Philosophy of Religion and Womanist Theology: An Introduction through Jacquelyn Grant’s Hermaneutics of Location” BOOK REVIEWS Mark David Wood: Cornel West and the Politics of Prophetic Pragmatism REVIEWED BY JOHN H. MCCLENDON III George Yancy, Ed.: Cornel West: A Critical Reader REVIEWED BY ARNOLD L. FARR © 2002 by The American Philosophical Association ISSN: 1067-9464 APA NEWSLETTER ON Philosophy and the Black Experience John McClendon & George Yancy, Co-Editors Fall 2002 Volume 02, Number 1 George Yancy’s recent groundbreaking work, Cornel West: A ETTER ROM THE EW DITORS Critical Reader. Farr particularly highlights the revolutionary L F N E historical importance of Yancy’s book. For submissions to the APA newsletter on Philosophy and the Black Experience, book reviews should be sent to George We would like to say that it is an honor to assume, as new Yancy at Duquesne University Philosophy Department, 600 editors, the helm of the APA Newsletter on Philosophy and the Forbes Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15282; and he can be e-mailed Black Experience. Editors Leonard Harris and Jesse Taylor have at [email protected]. Articles for submission can done a consistent job of providing us with articles and reviews be sent to John H. McClendon, Associate Professor of African that reflect the importance of philosophy vis-a-vis the Black American and American Cultural Studies, Bates College, 223 experience. -

Theodicy: an Overview

1 Theodicy: An Overview Introduction All of us struggle at one time or another in life with why evil happens to someone, either ourselves, our family, our friends, our nation, or perhaps some particularly disturbing instance in the news—a child raped, a school shooting, genocide in another country, a terrorist bombing. The following material is meant to give an overview of the discussion of this issue as it takes place in several circles, especially that of the Christian church. I. The Problem of Evil Defined Three terms, "the problem of evil," "theodicy," and "defense" are important to our discussion. The first two are often used as synonyms, but strictly speaking the problem of evil is the larger issue of which theodicy is a subset because one can have a secular problem of evil. Evil is understood as a problem when we seek to explain why it exists (Unde malum?) and what its relationship is to the world as a whole. Indeed, something might be considered evil when it calls into question our basic trust in the order and structure of our world. Peter Berger in particular has argued that explanations of evil are necessary for social structures to stay themselves against chaotic forces. It follows, then, that such an explanation has an impact on the whole person. As David Blumenthal observes, a good theodicy is one that has three characteristics: 1. "[I]t should leave one with one’s sense of reality intact." (It tells the truth about reality.) 2. "[I]t should leave one empowered within the intellectual-moral system in which one lives." (Namely, it should not deny God’s basic power or goodness.) 3. -

Names of God KOG 1/24/21

Names of God (week of feb 7) start here This week's name - Adonai - is the plural version of the word Adon which means ‘master’ or ‘ ruler.’ Adonai is pluralized because God is made up of plurality - Father, Son, Holy Spirit. This name, perhaps more than any other we have covered so far, has a deep impact on how we live our lives - because God is Adonai - or ruler - that means we are people who are being ruled. It means we are called, as God’s own creation, to submit to his rule over our lives. This can be a scary thing to think about and it can be a hard thing to let go of the control we have over our own lives, especially when we as humans tend to fall into the trap of thinking that we know best. Helping our children learn from a young age that submitting to God as our ruler isn’t scary at all - but it is actually freeing. READ THIS Psalm 97:5, Psalm 50:10. In this passage, the word Lord is translated into Adonai. The second reading from the Psalms reveals that he is claiming himself as the owner. dive deeper This week we are learning about the name Adonai - there are two important things to note about Adonai. First, it is a name that is plural. The original word is Adon, which means master. Adonai is the plural of the word Adon. It is important to know that this name is plural - because it is speaking about God in three ways - Father, Son, and Holy Spirit! This means that God is our ruler, Jesus (son) is our ruler, Holy Spirit is our ruler. -

Privatizing Religion: the Transformation of Israel's

Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious- Zionist community BY Yair ETTINGER The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. This paper is part of a series on Imagining Israel’s Future, made possible by support from the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund. The views expressed in this report are those of its author and do not represent the views of the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund, their officers, or employees. Copyright © 2017 Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu Table of Contents 1 The Author 2 Acknowlegements 3 Introduction 4 The Religious Zionist tribe 5 Bennett, the Jewish Home, and religious privatization 7 New disputes 10 Implications 12 Conclusion: The Bennett era 14 The Center for Middle East Policy 1 | Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious-Zionist community The Author air Ettinger has served as a journalist with Haaretz since 1997. His work primarily fo- cuses on the internal dynamics and process- Yes within Haredi communities. Previously, he cov- ered issues relating to Palestinian citizens of Israel and was a foreign affairs correspondent in Paris. Et- tinger studied Middle Eastern affairs at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and is currently writing a book on Jewish Modern Orthodoxy. -

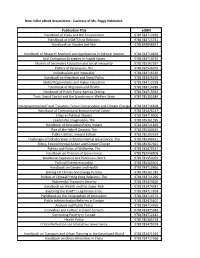

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Interpreting the Theology of Barth in Light of Nietzsche's Dictum “God Is Dead”

Interpreting the theology of Barth in light of Nietzsche’s dictum “God is dead” André J Groenewald Pastor: Presbyterian Church of Scotland Edinburgh, Scotland Abstract Karl Barth responded with his theology to Nietzsche’s dictum “God is dead” by stating that God is the living God. God does not need the human race to exist. God reveals God self to humankind whenever God wills. Barth agreed with Nietzsche that the god of the nineteenth century was a “Nicht-Gott”. The article aims to discus Karl Barth’s respons to Nietzsche’s impulse towards the development of a concept of God that would lead to neither atheism nor theism. The article argues that Barth paved the way for talking about God by defining God as the “communicative God”. 1. INTRODUCTION In his book, Die fröhliche Wissenschaft, originally written in 1882, Nietzsche tells about a mad man who runs around in a marketplace looking for “God” (Nietzsche 1973:159). Since he cannot find God, he can only reach one conclusion. God is dead! Nietzsche did not per se deny or affirm the existence of God. He announced the death of the god of modernity (Ward [1997] 1998:xxix; Groenewald 2005:146). He had a problem with the notion of “Fortschritt” according to which history has proven that human beings develop to greater heights of their own accord and that the potential for progress is intrinsic to humankind (Nietzsche 1969a:169; 1972: 304, 309, 310; see Jensen 2006:47, 51). “God’s existence and providence could then be proven on account of this optimistic progress in the course of history” (Groenewald 2005:146).