Dal Review 93 9.Pdf (237.9Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HARD FACTS and SOFT SPECULATION Thierry De Duve

THE STORY OF FOUNTAIN: HARD FACTS AND SOFT SPECULATION Thierry de Duve ABSTRACT Thierry de Duve’s essay is anchored to the one and perhaps only hard fact that we possess regarding the story of Fountain: its photo in The Blind Man No. 2, triply captioned “Fountain by R. Mutt,” “Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz,” and “THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS,” and the editorial on the facing page, titled “The Richard Mutt Case.” He examines what kind of agency is involved in that triple “by,” and revisits Duchamp’s intentions and motivations when he created the fictitious R. Mutt, manipulated Stieglitz, and set a trap to the Independents. De Duve concludes with an invitation to art historians to abandon the “by” questions (attribution, etc.) and to focus on the “from” questions that arise when Fountain is not seen as a work of art so much as the bearer of the news that the art world has radically changed. KEYWORDS, Readymade, Fountain, Independents, Stieglitz, Sanitary pottery Then the smell of wet glue! Mentally I was not spelling art with a capital A. — Beatrice Wood1 No doubt, Marcel Duchamp’s best known and most controversial readymade is a men’s urinal tipped on its side, signed R. Mutt, dated 1917, and titled Fountain. The 2017 centennial of Fountain brought us a harvest of new books and articles on the famous or infamous urinal. I read most of them in the hope of gleaning enough newly verified facts to curtail my natural tendency to speculate. But newly verified facts are few and far between. -

Plastic Dynamism in Pastel Modernism: Joseph Stella's

PLASTIC DYNAMISM IN PASTEL MODERNISM: JOSEPH STELLA’S FUTURIST COMPOSITION by MEREDITH LEIGH MASSAR Bachelor of Arts, 2007 Baylor University Waco, Texas Submitted to the Faculty Graduate Division College of Fine Arts Texas Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2010 ! ""! PLASTIC DYNAMISM IN PASTEL MODERNISM: JOSEPH STELLA’S FUTURIST COMPOSITION Thesis approved: ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite, Major Professor ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Frances Colpitt ___________________________________________________________________________ Rebecca Lawton, Curator, Amon Carter Museum ___________________________________________________________________________ H. Joseph Butler, Graduate Studies Representative For the College of Fine Arts ! """! Copyright © 2009 by Meredith Massar. All rights reserved ! "#! ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to all those who have assisted me throughout my graduate studies at Texas Christian University. Thank you to my professors at both TCU and Baylor who have imparted knowledge and guidance with great enthusiasm to me and demonstrated the academic excellence that I hope to emulate in my future career. In particular I would like to recognize Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite for his invaluable help and direction with this thesis and the entire graduate school experience. Many thanks also to Dr. Frances Colpitt and Rebecca Lawton for their wisdom, suggestions, and service on my thesis committee. Thank you to Chris for the constant patience, understanding, and peace given throughout this entire process. To Adrianna, Sarah, Coleen, and Martha, you all have truly made this experience a joy for me. I consider myself lucky to have gone through this with all of you. Thank you to my brothers, Matt and Patrick, for providing me with an unending supply of laughter and support. -

Representations of the Female Nude by American

© COPYRIGHT by Amanda Summerlin 2017 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BARING THEMSELVES: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE FEMALE NUDE BY AMERICAN WOMEN ARTISTS, 1880-1930 BY Amanda Summerlin ABSTRACT In the late nineteenth century, increasing numbers of women artists began pursuing careers in the fine arts in the United States. However, restricted access to institutions and existing tracks of professional development often left them unable to acquire the skills and experience necessary to be fully competitive in the art world. Gendered expectations of social behavior further restricted the subjects they could portray. Existing scholarship has not adequately addressed how women artists navigated the growing importance of the female nude as subject matter throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I will show how some women artists, working before 1900, used traditional representations of the figure to demonstrate their skill and assert their professional statuses. I will then highlight how artists Anne Brigman’s and Marguerite Zorach’s used modernist portrayals the female nude in nature to affirm their professional identities and express their individual conceptions of the modern woman. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I could not have completed this body of work without the guidance, support and expertise of many individuals and organizations. First, I would like to thank the art historians whose enlightening scholarship sparked my interest in this topic and provided an indispensable foundation of knowledge upon which to begin my investigation. I am indebted to Kirsten Swinth's research on the professionalization of American women artists around the turn of the century and to Roberta K. Tarbell and Cynthia Fowler for sharing important biographical information and ideas about the art of Marguerite Zorach. -

An Artist of the American Renaissance : the Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1883-1919 PDF

An Artist of the American Renaissance : The Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1883-1919 PDF Author: H. Wayne Morgan Pages: 197 pages ISBN: 9780873385176 Kenyon Cox was born in Warren, Ohio, in 1856 to a nationally prominent family. He studied as an adolescent at the McMicken Art School in Cincinnati and later at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. From 1877 to 1882, he was enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, and then in 1883 he moved to New York city, where he earned his living as an illustrator for magazines and books and showed easel works in exhibitions. He eventually became a leading painter in the classical style-particularly of murals in state capitols, courthouses, and other major buildings-and one of the most important traditionalist art critics in the United States.An Artist of the American Renaissance is a collection of Cox's private correspondence from his years in New York City and the companion work to editor H. Wayne Morgan's An American Art Student in Paris: The Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1877-1882 (Kent State University Press, 1986). These frank, engaging, and sometimes naive and whimsical letters show Cox's personal development as his career progressed. They offer valuable comments on the inner workings of the American art scene and describe how the artists around Cox lived and earned incomes. Travel, courtship of the student who became his wife, teaching, politics of art associations, the process of painting murals, the controversy surrounding the depiction of the nude, promotion of the new American art of his day, and his support of a modified classical ideal against the modernism that triumphed after the 1913 Armory Show are among the subjects he touched upon.Cox's letters are little known and have never before been published. -

'A Baby's Unconsciousness' in Sculpture: Modernism, Nationalism

Emily C. Burns ‘A baby’s unconsciousness’ in sculpture: modernism, nationalism, Frederick MacMonnies and George Grey Barnard in fin-de-siècle Paris In 1900 the French critic André Michel declared the US sculpture on view at the Exposition Universelle in Paris as ‘the affirmation of an American school of sculpture’.1 While the sculptors had largely ‘studied here and … remained faithful to our salons’, Michel concluded, ‘the influence of their social and ethnic milieu is already felt in a persuasive way among the best of them’.2 How did Michel come to declare this uniquely American school? What were the terms around which national temperament – what Michel describes as a ‘social and ethnic milieu’ – was seen as manifest in art? Artistic migration to Paris played a central role in the development of sculpture in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Hundreds of US sculptors trained in drawing and modelling the human figure at the Ecole des beaux-arts and other Parisian ateliers.3 The circulation of people and objects incited a widening dialogue about artistic practice. During the emergence of modernism, debates arose about the relationships between tradition and innovation.4 Artists were encouraged to adopt conventions from academic practice, and subsequently seek an individuated intervention that built on and extended that art history. Discussions about emulation and invention were buttressed by political debates about cultural nationalism that constructed unique national schools.5 In 1891, for example, a critic bemoaned that US artists were imitative in their ‘thoughtless acceptance of whatever comes from Paris’.6 By this period, US artists were coming under fire for so fully adopting French academic approaches that their art seemed inextricably tied to its foreign model. -

The Painted Word a Bantam Book / Published by Arrangement with Farrar, Straus & Giroux

This edition contains the complete text of the original hardcover edition. NOT ONE WORD HAS BEEN OMITTED. The Painted Word A Bantam Book / published by arrangement with Farrar, Straus & Giroux PUBLISHING HISTORY Farrar, Straus & Giroux hardcover edition published in June 1975 Published entirely by Harper’s Magazine in April 1975 Excerpts appeared in the Washington Star News in June 1975 The Painted Word and in the Booh Digest in September 1975 Bantam mass market edition / June 1976 Bantam trade paperback edition / October 1999 All rights reserved. Copyright © 1975 by Tom Wolfe. Cover design copyright © 1999 by Belina Huey and Susan Mitchell. Book design by Glen Edelstein. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-8978. No part o f this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information address: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 19 Union Square West, New York, New York 10003. ISBN 0-553-38065-6 Published simultaneously in the United States and Canada Bantam Books are published by Bantam Books, a division of Random House, Inc. Its trademark, consisting of the words “Bantam Books” and the portrayal of a rooster, is Registered in U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and in other countries. Marca Registrada. Bantam Books, New York, New York. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BVG 10 9 I The Painted Word PEOPLE DON’T READ THE MORNING NEWSPAPER, MAR- shall McLuhan once said, they slip into it like a warm bath. -

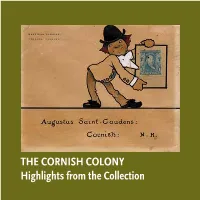

The Cornish Colony Highlights from the Collection the Cornish Colony Highlights from the Collection

THE CORNISH COLONY Highlights from the Collection THE CORNISH COLONY Highlights from the Collection The Cornish Colony, located in the area of Cornish, New The Cornish Colony did not arise all of apiece. No one sat down at Hampshire, is many things. It is the name of a group of artists, a table and drew up plans for it. The Colony was organic in nature, writers, garden designers, politicians, musicians and performers the individual members just happened to share a certain mind- who gathered along the Connecticut River in the southwest set about American culture and life. The lifestyle that developed corner of New Hampshire to live and work near the great from about 1883 until somewhere between the two World Wars, American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The Colony is also changed as the membership in the group changed, but retained a place – it is the houses and landscapes designed in a specific an overriding aura of cohesiveness that only broke down when the Italianate style by architect Charles Platt and others. It is also an country’s wrenching experience of the Great Depression and the ideal: the Cornish Colony developed as a kind of classical utopia, two World Wars altered American life for ever. at least of the mind, which sought to preserve the tradition of the —Henry Duffy, PhD, Curator Academic dream in the New World. THE COLLECTION Little is known about the art collection formed by Augustus Time has not been kind to the collection at Aspet. Studio fires Saint-Gaudens during his lifetime. From inventory lists and in 1904 and 1944 destroyed the contents of the Paris and New correspondence we know that he had a painting by his wife’s York houses in storage. -

Duchamp's Labyrinth: First Papers of Surrealism, 1942*

Duchamp’s Labyrinth: First Papers of Surrealism, 1942* T. J. DEMOS Entwined Spaces In October of 1942, two shows opened in New York within one week of each other, both dedicated to the exhibition of Surrealism in exile, and both represent- ing key examples of the avant-garde’s forays into installation art. First Papers of Surrealism, organized by André Breton, opened first. The show was held in the lavish ballroom of the Whitelaw Reid mansion on Madison Avenue at Fiftieth Street. Nearly fifty artists participated, drawn from France, Switzerland, Germany, Spain, and the United States, representing the latest work of an internationally organized, but geopolitically displaced, Surrealism. The “First Papers” of the exhibition’s title announced its dislocated status by referring to the application papers for U.S. citi- zenship, which emigrating artists (including Breton, Ernst, Masson, Matta, Duchamp, and others) encountered when they came to New York between 1940 and 1942. But the most forceful sign of the uprooted context of Surrealism was the labyrinthine string installation that dominated the gallery, conceived by Marcel Duchamp, who had arrived in New York from Marseilles in June of that year. The disorganized web of twine stretched tautly across the walls, display parti- tions, and the chandelier of the gallery, producing a surprising barrier that intervened in the display of paintings.1 The second exhibition was the inaugural show of Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery on Fifty-seventh Street, which displayed her collection of Surrealist and abstract art. Guggenheim gave Frederick Kiesler free rein to design *I am grateful for the support and criticism of Benjamin H. -

Rose Standish Nichols and the Cornish Art Colony

Life at Mastlands: Rose Standish Nichols and the Cornish Art Colony Maggie Dimock 2014 Julie Linsdell and Georgia Linsdell Enders Research Intern Introduction This paper summarizes research conducted in the summer of 2014 in pursuit of information relating to the Nichols family’s life at Mastlands, their country home in Cornish, New Hampshire. This project was conceived with the aim of establishing a clearer picture of Rose Standish Nichols’s attachment to the Cornish Art Colony and providing insight into Rose’s development as a garden architect, designer, writer, and authority on garden design. The primary sources consulted consisted predominantly of correspondence, diaries, and other personal ephemera in several archival collections in Boston and New Hampshire, including the Nichols Family Papers at the Nichols House Museum, the Rose Standish Nichols Papers at the Houghton Library at Harvard University, the Papers of the Nichols-Shurtleff Family at the Schlesinger Library at the Radcliffe Institute, and the Papers of Augustus Saint Gaudens, the Papers of Maxfield Parrish, and collections relating to several other Cornish Colony artists at the Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth College. After examining large quantities of letters and diaries, a complex portrait of Rose Nichols’s development emerges. These first-hand accounts reveal a woman who, at an early age, was intensely drawn to the artistic society of the Cornish Colony and modeled herself as one of its artists. Benefitting from the influence of her famous uncle Augustus Saint Gaudens, Rose was given opportunities to study and mingle with some of the leading artistic and architectural luminaries of her day in Cornish, Boston, New York, and Europe. -

Misfired Canon (A Review of the New Moma)

NEW YORK NEW MOMA WINTER 2020 WINTER / OPENED OCTOBER 21 news ART At the new MoMA, Faith Ringgold’s 1967 painting American People Series No. 20: Die (below) is paired with Picasso’s famed 1907 canvas Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Misfred Canon A feminist curator fnds the rehang seriously lacking. BY MAURA REILLY URING THE 1990S, WHILE and, ultimately, Jackson Pollock. According by my boss from cheekily offering a tour of pursuing my graduate art history to Barr, “modern art” was a synchronic, “women artists in the collection” at a time degree at New York University, I linear flow of “isms” in which one (hetero- when there were only eight on view. worked in the Education Depart- sexual, white) male “genius” from Europe or By the turn of the 21st century, the rele- Dment of the Museum of Modern Art, where the U.S. influenced another who inevitably vance of mainstream modernism was being I led gallery tours of the museum’s perma- trumped or subverted his previous master, challenged, and anti-chronology became nent collection for the general public and thereby producing an avant-garde progres- all the rage. The Brooklyn Museum, the VIPs. At that time, the permanent exhibition sion. Barr’s story was so ingrained in the High Museum of Art, and the Denver Art galleries, representing art produced from institution that it was never questioned as Museum all rehung their collections accord- 1880 to the mid-1960s, were arranged to problematic. The fact that very few women, ing to subject instead of chronology, and a tell the “story” of modern art as conceived artists of color, and those not from Europe much-anticipated inaugural exhibition at by founding director Alfred H. -

The Other Side of American Exceptionalism: Thematic And

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1999 The other side of American exceptionalism: thematic and stylistic affinities in the paintings of the Ashcan School and in Mark Twain's Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven Ng Lee Chua Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Chua, Ng Lee, "The other side of American exceptionalism: thematic and stylistic affinities in the paintings of the Ashcan School and in Mark Twain's Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven" (1999). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16258. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16258 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The other side of American ExceptionaIism: Thematic and stylistic affinities in the paintings of the Ashcan School and in Mark Twain's Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven by Ng Lee Chua A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Major Professor: Constance J. Post Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1999 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is -

FAMOUS AMERICAN WOMEN PAINTERS by ARTHUR HOEBER Author, Artist, and Critic

[OUSAMERIOIN OMEN PAINTER DEPARTMENT O] HNE ARTS irial Number 55 m\t i TJUf mtJm The Mentor Association )R THE DEVELOPMENT OF :; ii\ ihREST IN ART, LITERATURE, TT MT<;TnRY, NATURE, AND TRAVEL THE ADVISORY BOARD University G, HIBBEN President of Princeton HAMILTON W, MABIE Author and Editor JOHN a FAN DYKE f the History of Arty Rutgers College ALBERT BUSHNELL HART Froj ior of Government^ Harvard University HILLIAM T.HORNADAY Director New York Zoological Park Traveler DiriGHT L ELMENDORF . Lecturer and THE PLAN OF THE ASSOCIATION purpose of The Mentor Association is to give its members, in an THEinteresting and attractive way, the information in various fields of knowledge which everybody wants and ought to have. The infor- under the mation is imparted by interesting reading matter, prepared the direction of leading authorities, and by beautiful pictures, produced by most highly perfected modern processes. The object of The Mentor Association is to enable people to acquire useful knowledge without effort, so that they may come easily and agree- ably to know the world's great men and women, the great achievements and the permancntlv interesting things in art, literature, science, history, nature, and travel. ^ , The annual membership fee is Three Dollars. Every member i. year. entitled to receive twenty-four numbers of The Mentor for one THE MENTOR •ncruTPTION. THREE DOLLARS A YEAR. AS SECOND-CLASS MATTER. COPYRIGHT. (PIESPIPTBEN CENTS. FOREIGN 1914. BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION. AND TREASURER. R. .. .6 EXTRA. CANADIAN INC. PRESIDENT CENTS W. M. '.(}£ 50 CENTS EXTRA. ENTERED M. DONALDSON; VICE-PRESIDENT. L. D. GARDNER .IE POST^PPICE AT NEW YORK.