Since Fewer, Instructional Days Would Mean the End of the Spring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACCREDITING COMMISSION for COMMUNITY and JUNIOR COLLEGES Western Association of Schools and Colleges

ACCREDITING COMMISSION FOR COMMUNITY AND JUNIOR COLLEGES Western Association of Schools and Colleges COMMISSION ACTIONS ON INSTITUTIONS At its January 6-8, 2016 meeting, the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges, Western Association of Schools and Colleges, took the following institutional actions on the accredited status of institutions: REAFFIRMED ACCREDITATION FOR 18 MONTHS ON THE BASIS OF A COMPREHENSIVE EVALUATION American River College Cosumnes River Folsom Lake College Sacramento City College Chabot College Las Positas College Citrus College Napa Valley College Santa Barbara City College Taft College ISSUED WARNING ON THE BASIS OF A COMPREHENSIVE EVALUATION Southwestern College REMOVED FROM WARNING ON THE BASIS OF A FOLLOW-UP REPORT WITH VISIT The Salvation Army College for Officer Training at Crestmont REMOVED SHOW CAUSE AND ISSUED WARNING ON THE BASIS OF A SHOW CAUSE REPORT WITH VISIT American Samoa Community College ELIGIBILITY DENIED California Preparatory College Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges January 2016 Commission Actions on Institutions THE COMMISSION REVIEWED THE FOLLOWING INSTITUTIONS AND CONTINUED THEIR ACCREDITED STATUS: MIDTERM REPORT Bakersfield College Cerro Coso Community College Porterville College College of the Sequoias Hawai’i Community College Honolulu Community College Kapi’olani Community College Kauai Community College Leeward Community College Windward Community College Woodland Community College Yuba College FOLLOW-UP REPORT Antelope Valley College De Anza College Foothill College Santa Ana College Windward Community College FOLLOW-UP REPORT WITH VISIT Contra Costa College Diablo Valley College Los Medanos College El Camino College Moreno Valley College Norco College Riverside City College Rio Hondo College . -

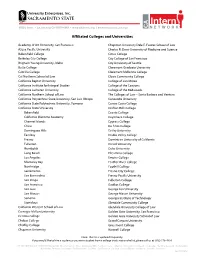

Affiliated Colleges and Universities

Affiliated Colleges and Universities Academy of Art University, San Francisco Chapman University Dale E. Fowler School of Law Azusa Pacific University Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science Bakersfield College Citrus College Berkeley City College City College of San Francisco Brigham Young University, Idaho City University of Seattle Butte College Claremont Graduate University Cabrillo College Claremont McKenna College Cal Northern School of Law Clovis Community College California Baptist University College of San Mateo California Institute for Integral Studies College of the Canyons California Lutheran University College of the Redwoods California Northern School of Law The Colleges of Law – Santa Barbara and Ventura California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo Concordia University California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Contra Costa College California State University Crafton Hills College Bakersfield Cuesta College California Maritime Academy Cuyamaca College Channel Islands Cypress College Chico De Anza College Dominguez Hills DeVry University East Bay Diablo Valley College Fresno Dominican University of California Fullerton Drexel University Humboldt Duke University Long Beach El Camino College Los Angeles Empire College Monterey Bay Feather River College Northridge Foothill College Sacramento Fresno City College San Bernardino Fresno Pacific University San Diego Fullerton College San Francisco Gavilan College San Jose George Fox University San Marcos George Mason University Sonoma Georgia Institute of Technology Stanislaus Glendale Community College California Western School of Law Glendale University College of Law Carnegie Mellon University Golden Gate University, San Francisco Cerritos College Golden Gate University School of Law Chabot College Grand Canyon University Chaffey College Grossmont College Chapman University Hartnell College Note: This list is updated frequently. -

FACULTY and ADMINISTRATORS Chapter Five Catalog 2020-2021

FACULTY AND ADMINISTRATORS chapter five catalog 2020-2021 Faculty and administrators 405 Index 411 404 FACULTY AND ADMINISTRATORS chapter five DIABLO VALLEY COLLEGE CATALOG 2020-2021 Faculty and administrators Faculty and administrators 405 FACULTY AND ADMINISTRATORS Abbott, Daniel Anisko, Melissa Barksdale, Jessica Index 411 faculty - architecture faculty - mathematics faculty - English B.A. - University of Oregon A.S. - San Joaquin Delta College B.A. - CSU Stanislaus B.S. - University of California, Davis M.A. - San Francisco State University Abedrabbo, Samar M.S. - University of California, Merced faculty - biology Beaulieu, Ellen A.A. - Irvine Valley Community College faculty - chemistry Antonakos, Cory B.S. - University of Georgia B.S. - University of California, Irvine faculty - chemistry P.h.D. - University of California, Santa B.S. - George Washington University Ph.D. - UC Berkeley Cruz M.S. - UC Berkeley Bennett, Troy faculty - art digital media Abele, Robert Aranda, Alberto B.F.A. - Plymouth State University faculty - counseling faculty - philosophy M.F.A. - Rochester Institute of Technology B.A. - University of Dayton certificate -CSU Los Angeles M.Div. - Mount St. Mary B.S., M.S. - CSU Los Angeles M.A. - Athenaeum of Ohio Bersamina, Leo Ph.D. - Marquette University faculty - art Arman, Beth A.A. - Cabrillo College senior dean - workforce development Agnost, Katy B.F.A. - San Francisco State University B.A. - University of Michigan, Ann Arbor M.F.A. - Yale University faculty – English M.A. - Harvard University, Kennedy B.A. - UC Davis School of Government M.A. - San Francisco State University Bessie, Adam faculty - English Akanyirige, Emmanuel Armendariz, Rosa B.A. - UC Davis faculty - mathematics dean - student engagement and equity M.A. -

WBL Publisher File (2) (Read-Only)

The Work-Based Learning Handbook 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS.............................................................................. 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS................................................................................................ 3 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 4 Work-based Learning Programs ................................................................................ 4 Mandatory Requirements for CWEE Work-based Learning Programs ..................... 4 California Code Regulations, Title V ......................................................................... 4 MODULE I. PLANNING A WORK-BASED LEARNING PROGRAM5 Types of CWEE programs........................................................................................... 5 General Work Experience Education ......................................................... 5 Occupational Work Experience Education................................................. 5 Types of CWEE plans: ................................................................................................ 5 Parallel Plan ................................................................................................ 5 Alternate Plan ............................................................................................. 6 Program Needs Assessment........................................................................................ 6 Advisory Committees ................................................................................ -

Campus & Future

Campus & Future: Questions for Planners Richard at Café Strada Star then Cubes...or, Star and Cubes Local and Regional Laboratory Campus Histories Early 20th Century 19th Century Mid 20th Century 21st Century Heritage Campus Framework of Buildings, Landscapes and Places of Interaction End of An Era Contentious Politics, Unrealistic Finances Bay Area Higher Education PUBLIC Berkeley City College-California Maritime Academy-California State University, East Bay-Canada College-Chabot College-City College of San Francisco-College-College of Alameda-College of Marin-College of San Mateo-Contra Costa College-De Anza College- Diablo Valley College-Evergreen Valley College-Foothill College-Laney College-Las Positas College-Los Medanos College-Merritt College-Mission College-Ohlone College-San Francisco State University-San Jose City College-Santa Rosa Junior College-Sonoma State University- Skyline College-Solano Community College-West Valley College-University of California, Berkeley-University of California, San Francisco-University of California, Hastings Law- PRIVATE Academy of Art University-California College of the Arts-California Culinary Academy-California Institute of Integral Studies-Carnegie Mellon Silicon Valley-Cogswell Polytechnical College-DeVry University-Dominican University-Ex’pression College for Digital Arts-Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising-Five Branches University-Holy Names University-Hult International Business School-International Technological University-John F. Kennedy University-Lincoln Law School-Lincoln -

California State University, California Community College Transfers by Campus Year 2012-2013

California State University, California Community College Transfers by Campus Year 2012-2013 1. DE ANZA COLLEGE 1,225 58. SKYLINE COLLEGE 326 2. ORANGE COAST COLLEGE 1,207 59. COLLEGE OF SAN MATEO 325 3. PALOMAR COLLEGE 1,077 60. MERCED COLLEGE 320 4. FULLERTON COLLEGE 1,072 61. SHASTA COLLEGE 315 5. EL CAMINO COLLEGE 1,032 62. SOLANO COLLEGE 310 6. MOUNT SAN ANTONIO COLLEGE 946 63. LOS ANGELES CITY COLLEGE 308 7. CITY COLLEGE OF SAN FRANCISCO 906 64. LOS ANGELES HARBOR COLLEGE 306 8. PASADENA CITY COLLEGE 903 65. COLLEGE OF THE DESERT 305 9. DIABLO VALLEY COLLEGE 856 66. LOS MEDANOS COLLEGE 302 10. SANTA MONICA COLLEGE 854 67. SAN DIEGO CITY COLLEGE 270 11. SADDLEBACK COLLEGE 799 68. SAN JOSE CITY COLLEGE 265 12. LONG BEACH CITY COLLEGE 773 69. ALLAN HANCOCK COLLEGE 262 13. SIERRA COLLEGE 759 70. FOLSOM LAKE COLLEGE3 254 14. BUTTE COLLEGE 755 71. MISSION COLLEGE 230 15. MOORPARK COLLEGE 736 72. CUYAMACA COLLEGE 227 16. SANTA ROSA JUNIOR COLLEGE 722 73. LANEY COLLEGE 221 17. FRESNO CITY COLLEGE 705 74. SAN DIEGO MIRAMAR COLLEGE 221 18. LOS ANGELES PIERCE COLLEGE 696 75. COLLEGE OF THE REDWOODS 220 19. AMERICAN RIVER COLLEGE 694 76. NAPA VALLEY COLLEGE 218 20. EAST LOS ANGELES COLLEGE 691 77. CONTRA COSTA COLLEGE 209 21. GROSSMONT COLLEGE 665 78. MONTEREY PENINSULA COLLEGE 204 22. CERRITOS COLLEGE 644 79. YUBA COLLEGE 200 23. BAKERSFIELD COLLEGE 628 80. VICTOR VALLEY COLLEGE 198 24. SAN JOAQUIN DELTA COLLEGE 610 81. SAN BERNARDINO VALLEY COLLEGE 197 25. MIRACOSTA COLLEGE 605 82. -

Hungry and Homeless in College

HUNGRY AND HOMELESS RESULTS FROM A NATIONAL STUDY IN COLLEGE: OF BASIC NEEDS INSECURITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION Sara Goldrick-Rab, Jed Richardson, and Anthony Hernandez Wisconsin HOPE Lab MARCH 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ..................................................................... 1 Coming Up Short: Basic Needs Insecurity on the College Campus ............................ 3 What We Know About Students and Basic Needs Insecurity .................................. 5 Methodology .......................................................................... 7 A Closer Look: Community College Students and Basic Needs Insecurity .....................11 Who are Homeless Undergraduates? .....................................................19 Improving Policy and Practice ...........................................................23 Appendix A ...........................................................................25 Appendix B ...........................................................................26 Endnotes .............................................................................27 The authors would like to thank the Association of Community College Trustees for recruiting institutional participants in this survey. We are grateful to Peter Kinsley for offering technical support for survey administration. We also thank Jacob Bray, Katharine M. Broton, Colleen Campbell, David Conner, and Ivy Love for providing editorial feedback. This project would not have been possible without the financial support of the Kresge Foundation. -

Analysis of the America Rescue Plan Federal Stimulus

MEMO March 12, 2021 TO: Chancellor Eloy Ortiz Oakley Chief Executive Officers Chief Business Officers Chief Student Services Officers Chief Instructional Officers FROM: Lizette Navarette, Vice Chancellor, College Finance and Facilities Planning David O’ Brien, Vice Chancellor, Government Relations RE: Analysis of the America Rescue Plan Federal Stimulus Summary On Thursday, March 11, 2021, President Joe Biden signed the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan into law. The new federal stimulus includes a robust investment in higher education with resources available for a longer period of time. Half of the resources each colleges receives will go to support direct emergency grants to students. Bill Details The new federal Coronavirus stimulus bill earmarks nearly $170 billion for education, including $39.6 billion for a third round of funding into the Higher Education Emergency Relief (HEER) Fund. The HEER III dollars will be allocated using the same methodology as the previous two iterations (with some slight modifications) and requires institutions that receive this funding to allocate at least 50% of those dollars to students in the form of emergency grants. One welcome distinction over previous stimulus bills is that the American Rescue Plan specifies funds will be available for use by institutions through September 30, 2023. Specifically, the $39 billion investment in the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund will be distributed as follows: • 37.5 percent based on FTE Pell recipients, not exclusively enrolled in distance education courses prior to the emergency; • 37.5 percent based on headcount Pell recipients; • 11.5 percent based on overall FTE students; • 11.5 percent based on overall headcount of students; • 1 percent based on FTE Pell exclusively online recipients (may only be used for student grants); and • 1 percent based on headcount Pell exclusively online recipients (may only be used for student grants). -

1 Santa Monica College 57 Rio Hondo Colege 2 De Anza

California Community College Total Transfers by Campus to University of California Year 2013-2014 1 SANTA MONICA COLLEGE 1,061 57 RIO HONDO COLEGE 87 2 DE ANZA COLLEGE 756 58 CUESTA COLLEGE 82 3 DIABLO VALLEY COLLEGE 741 59 FOLSOM LAKE COLLEGE 80 4 SANTA BARBARA CITY COLLEGE 536 60 MODESTO JUNIOR COLLEGE 77 5 PASADENA CITY COLLEGE 512 61 MERCED COLLEGE 74 6 ORANGE COAST COLLEGE 490 62 ALLAN HANCOCK COLLEGE 73 7 FOOTHILL COLLEGE 429 63 COLLEGE OF ALAMEDA 71 8 MOUNT SAN ANTONIO COLLEGE 424 64 CONTRA COSTA COLLEGE 70 9 IRVINE VALLEY COLLEGE 397 65 FRESNO CITY COLLEGE 70 10 EL CAMINO COLLEGE 386 66 ANTELOPE VALLEY COLLEGE 68 11 CITY COLLEGE OF SAN FRANCISCO 362 67 MONTEREY PENINSULA COLLEGE 68 12 MOORPARK COLLEGE 318 68 MISSION COLLEGE 66 13 SADDLEBACK COLLEGE 314 69 CUYAMACA COLLEGE 65 14 RIVERSIDE COLLEGE 298 70 NORCO COLLEGE 64 15 LOS ANGELES PIERCE COLLEGE 291 71 REEDLEY COLLEGE 58 16 MIRACOSTA COLLEGE 282 72 SAN BERNARDINO VALLEY COLLEGE 57 17 GLENDALE COLLEGE 277 73 SHASTA COLLEGE 55 18 SACRAMENTO CITY COLLEGE 263 74 SAN DIEGO CITY COLLEGE 53 19 SANTA ROSA JUNIOR COLLEGE 256 75 VICTOR VALLEY COLLEGE 53 20 SAN DIEGO MESA COLLEGE 249 76 COLLEGE OF THE DESERT 50 21 EAST LOS ANGELES COLLEGE 247 77 EVERGREEN VALLEY COLLEGE 50 22 AMERICAN RIVER COLLEGE 234 78 BUTTE COLLEGE 47 23 FULLERTON COLLEGE 219 79 SAN JOSE CITY COLLEGE 47 24 CABRILLO COLLEGE 207 80 CANADA COLLEGE 46 25 PALOMAR COLLEGE 196 81 WOODLAND COLLEGE 45 26 OHLONE COLLEGE 189 82 MERRITT COLLEGE 43 27 SIERRA COLLEGE 183 83 BAKERSFIELD COLLEGE 42 28 COLLEGE OF THE CANYONS 168 84 -

Faculty and Staff Diversity at College of Marin, the Bay Area 10, and Santa Rosa Junior College September 2015

Faculty and Staff Diversity at College of Marin, the Bay Area 10, and Santa Rosa Junior College September 2015 Introduction This research compares College of Marin (COM) to the 20 community colleges at the other 9 districts in the Bay Area (Bay-10) and Santa Rosa Junior College (SRJC). Using the Fall 2014 data from the California Community College Chancellor’s Office (CCCCO) DataMart, we looked at each college’s employee diversity and the extent to which it reflects the student population. The purpose of this research is to help inform the process of student equity planning. Recent research found improved academic performance and long-term outcomes for minority students who are taught by minority faculty. Based on this research, the Community College League of California (CCLC) has recommended that faculty members reflecting the diversity of the student population participate in the formulation and implementation of the schools’ student equity plans.1 Therefore this report is particularly concerned with noting disparities between minority student populations and faculty, though we include comparisons by college for all employees, and disaggregated by faculty, classified staff, and administration. For each major race/ethnic category, we considered differences of less than 2 percentage points between the student population and employees as equivalent. In some cases, the percentage gap is much larger than 2%. While there is no research standard for gauging the equivalence of race/ethnicity, we are setting a conservative standard of equivalence to assure that statistical differences are highlighted. In practice, in terms of whether students are likely to see themselves represented among campus employees, this may be a narrow band, but the purpose of this report is to show the differences in the data so that colleges can use it for their own planning. -

Chapter Five Catalog 2018-2019

FACULTY AND ADMINISTRATORS chapter five catalog 2018-2019 Faculty and administrators 375 Index 383 374 FACULTY AND ADMINISTRATORS chapter five DIABLO VALLEY COLLEGE CATALOG 2018-2019 Faculty and administrators Faculty and administrators 375 FACULTY AND ADMINISTRATORS Index 383 Abbott, Daniel Armstrong, Terry L. Bersamina, Leo faculty - architecture faculty - counseling faculty - art B.A. - University of Oregon B.A., M.A. - CSU Fresno A.A. - Cabrillo College B.F.A. - San Francisco State University Abele, Robert Bailey, Jamie Lynn M.F.A. - Yale University faculty - philosophy faculty - counseling B.A. - University of Dayton B.A., M.A. - CSU Hayward Bessie, Adam M.Div. - Mount St. Mary faculty - English M.A. - Athenaeum of Ohio Bairos, Monte B.A. - UC Davis Ph.D. - Marquette University faculty - music M.A. - San Francisco State University A.A. - Merced College Agnost, Katy B.A. - CSU Stanislaus Black, Bethallyn faculty – English M.M. - University of Colorado, Boulder faculty - horticulture B.A. - UC Davis B.A., M.A. - New College of CA M.A. - San Francisco State University Ballif, Daniela fiscal services manager B.S. - University of Tirana Blackwell-Stratton, Marian Akanyirige, Emmanuel faculty - English M.B.A. - Brigham Young University faculty - mathematics B.A. - UC Berkeley B.S., M.S. - Ball State University Barber, Thomas P. M.F.A. - Mills College Akiyama, Mark faculty - English Brecha, Jane faculty - psychology B.A. - Saint Mary’s College faculty - mathematics B.A, - UC Berkeley M.A.- San Francisco State University B.A. - UC Santa Cruz Ph.D. - University of Michigan M.F.A. - Pacific Lutheran University M.S. - CSU Hayward Alves, Stephanie Barksdale, Jessica faculty - English Breton, Hopi registrar faculty - art A.A. -

Chapter Five Catalog 2021-2022

FACULTY AND ADMINISTRATORS chapter five catalog 2021-2022 Faculty and administrators 427 Index 435 426 FACULTY AND ADMINISTRATORS chapter five DIABLO VALLEY COLLEGE CATALOG 2021-2022 Faculty and administrators Faculty and administrators 427 FACULTY AND ADMINISTRATORS Abbott, Daniel Anisko, Melissa Beaulieu, Ellen Index 435 faculty - architecture faculty - mathematics faculty - chemistry B.A. - University of Oregon A.S. - San Joaquin Delta College B.S. - University of Georgia B.S. - University of California, Davis Ph.D. - UC Berkeley Abedrabbo, Samar M.S. - University of California, Merced faculty - biology Bennett, Troy A.A. - Irvine Valley Community College faculty - art digital media Ansari-Yan, Durrain B.F.A. - Plymouth State University B.S. - University of California, Irvine faculty - health science P.h.D. - University of California, Santa B.S.. - UCLA M.F.A. - Rochester Institute of Technology Cruz M.S. - UC Berkeley Bernhardt, Paul J. Abele, Robert Antonakos, Cory faculty - culinary arts faculty - philosophy A.S. - Johnson & Wales University faculty - chemistry B.E.. - San Francisco State University B.A. - University of Dayton B.S. - George Washington University M.Div. - Mount St. Mary M.S. - UC Berkeley M.A. - Athenaeum of Ohio Bersamina, Leo Ph.D. - Marquette University faculty - art Aranda, Alberto A.A. - Cabrillo College faculty - counseling Agnost, Katy B.F.A. - San Francisco State University certificate -CSU Los Angeles M.F.A. - Yale University faculty – English B.S., M.S. - CSU Los Angeles B.A. - UC Davis M.A. - San Francisco State University Bessie, Adam Arman, Beth faculty - English Akanyirige, Emmanuel senior dean - workforce development B.A. - UC Davis faculty - mathematics B.A.