The ACT and Its Region: Economic Relationships and Key Drivers of Economic Growth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hume Coal Project RTS Appendix 5

Hume Coal Project — Response to Submissions - VOLUME 3 Appendix 5 Hume Coal Project – Response to community concerns regarding impacts on tourism (Judith Stubbs & Associates 2017) www.emmconsulting.com.au Hume Coal Project — Response to Submissions - VOLUME 3 www.humecoal.com.au Hume Coal Project: Response to Community Concerns regarding impacts on tourism 14 November 2017 This report has been prepared for Hume Coal Pty Limited by The Old Post Office 231 Princes Hwy, Bulli NSW 2516 Ph: 02 4283 7300 [email protected] www.judithstubbs.com.au This Report has been prepared by: Judith Stubbs BSW PhD MPIA John Storer, BE (Civil), Grad Dip (Econ) Disclaimer © Judith Stubbs & Associates All Rights Reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, transmitted, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language in any form by any means without the written permission of Judith Stubbs & Associates. Intellectual Property Rights All Rights Reserved. All methods, processes, commercial proposals and other contents described in this document are the confidential intellectual property of Judith Stubbs & Associates and may not be used or disclosed to any party without the written permission of Judith Stubbs & Associates. Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary ....................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Project ............................................................................................................ 1 1.3 Importance of the Tourist Industry in the Locality ................................................... 2 1.4 Current Co-Existence of Industrial and Tourism Uses and Activities in the Locality . 3 1.5 Future Impacts of the Proposed Mine on Tourism Uses and Activities in the Locality3 1.6 Statistical Relationship between Coal Mining and Tourism Industries in NSW ........ -

Regional Tourism Statistics in Australia Occasional Paper Number 1

Regional Tourism Statistics in Australia Occasional Paper Number 1 Stephanie Hunt Gary Prosser Editors An outcome of the Regional Tourism Statistics Workshop Sydney 29 September 1998 Regional Tourism Statistics in Australia Occasional Paper Number 1 Stephanie Hunt and Gary Prosser (Editors) ISBN 1 86384 4449 X © 1998 Centre for Regional Tourism Research No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by means of electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any inquiries should be directed to the Centre for Regional Tourism Research, Southern Cross University, PO Box 157, Lismore NSW 2480 Australia. Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................1 Tourism Statistics and Regional Tourism Development .....................................3 State Agency Perspective .............................................................................4 Large Operator Perspective .........................................................................6 Small Operator Perspective .........................................................................7 National Tourism Data Collections .......................................................................9 International Visitor Survey .........................................................................9 Domestic Tourism Monitor ........................................................................10 -

The Economic Importance of Tourism in Australia's Regions

The Economic Importance of Tourism in Australia’s Regions ISBN 978-1-921812-27-9 Tourism Research Australia GPO Box 1564 Canberra ACT 2601 Phone: 6243 7745 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ret.gov.au/tra Publication date: April 2011 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes and diagrams it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material. This work should be attributed as The Economic Importance of Tourism in Australia’s Regions, Tourism Research Australia, Canberra. Enquiries regarding the licence and any use of work by Tourism Research Australia are welcome at [email protected] Contents 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1 2 Australia’s tourism regions ................................................................................... 1 3 Methodology ...................................................................................................... 5 4 Results .............................................................................................................. 6 5 Conclusion ....................................................................................................... 11 Appendices Appendix A: Detailed methodology ...................................................................... 12 A1 Tourism output ....................................................................................... -

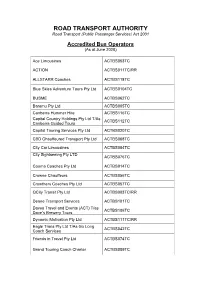

Accredited Bus Operators (As at June 2020)

ROAD TRANSPORT AUTHORITY Road Transport (Public Passenger Services) Act 2001 Accredited Bus Operators (As at June 2020) Ace Limousines ACTBS053TC ACTION ACTBS011TC/RR ALLSTARR Coaches ACTBS118TC Blue Skies Adventure Tours Pty Ltd ACTBS0104TC BUSME ACTBS062TC Baromu Pty Ltd ACTBS005TC Canberra Hummer Hire ACTBS116TC Capital Country Holdings Pty Ltd T/As ACTBS112TC Canberra Guided Tours Capital Touring Services Pty Ltd ACTBS020TC CBD Chauffeured Transport Pty Ltd ACTBS068TC City Car Limousines ACTBS084TC City Sightseeing Pty LTD ACTBS076TC Cooma Coaches Pty Ltd ACTBS014TC Crowne Chauffeurs ACTBS056TC Crowthers Coaches Pty Ltd ACTBS057TC QCity Transit Pty Ltd ACTBS003TC/RR Deane Transport Services ACTBS101TC Daves Travel and Events (ACT) T/as ACTBS106TC Dave’s Brewery Tours Dynamic Motivation Pty Ltd ACTBS111TC/RR Eagle Trans Pty Ltd T/As Go Long ACTBS042TC Coach Services Friends in Travel Pty Ltd ACTBS074TC Grand Touring Coach Charter ACTBS009TC Greyhound Australia Pty Ltd ACTBS034TC Horizon Coach Charters ACTBS081TC Hummingbird Charters T/As ACTBS071TC Snow Alliance Keir’s Group Of Companies Pty Ltd ACTBS015TC Kennedys Bus & Coach ACTBS078TC KMET Transport Services Pty Ltd ACTBS070TC T/As Roadcoach Lanaad Pty Ltd ATF DM Charters ACTBS117TC Trust Makeham’s Coaches ACTBS026TC Marulan Truck & Bus Pty Ltd T/as ACTBS121TC Marulan Coaches Marshall’s Bus & Coach company ACTBS036TC PTY Ltd Michael Minter T/as Voorpret ACTBS124TC Monaro Coaches ACTBS022TC Moonlight Stretch Limo Pty Ltd ACTBS085TC Murrays Australia PTY LTD ACTBS010TC North Sydney -

Review of the Posted Speed Limit on the Gungahlin Drive Extension

14 February 2012 Review of the Posted Speed Limit on the Gungahlin Drive Extension AECOM Review of the Posted Speed Limit on the Gungahlin Drive Extension Review of the Posted Speed Limit on the Gungahlin Drive Extension Prepared for Roads ACT Prepared by AECOM Australia Pty Ltd Level 2, 60 Marcus Clarke Street, Canberra ACT 2600, Australia T +61 2 6201 3000 F +61 2 6201 3099 www.aecom.com ABN 20 093 846 925 14 February 2012 AECOM in Australia and New Zealand is certified to the latest version of ISO9001 and ISO14001. © AECOM Australia Pty Ltd (AECOM). All rights reserved. AECOM has prepared this document for the sole use of the Client and for a specific purpose, each as expressly stated in the document. No other party should rely on this document without the prior written consent of AECOM. AECOM undertakes no duty, nor accepts any responsibility, to any third party who may rely upon or use this document. This document has been prepared based on the Client’s description of its requirements and AECOM’s experience, having regard to assumptions that AECOM can reasonably be expected to make in accordance with sound professional principles. AECOM may also have relied upon information provided by the Client and other third parties to prepare this document, some of which may not have been verified. Subject to the above conditions, this document may be transmitted, reproduced or disseminated only in its entirety. \\AUCBR1FP001\Projects\60092506 - GDE Stage 2\8. Issued Documents\8.1 Reports\GDE Speed review\GDE stage 2 Speed Limits 20120214.docx Revision - 14 February 2012 AECOM Review of the Posted Speed Limit on the Gungahlin Drive Extension Quality Information Document Review of the Posted Speed Limit on the Gungahlin Drive Extension Ref Date 14 February 2012 Prepared by Peter Evans Reviewed by Rod Weeks, Tom Brimson Revision History Authorised Revision Revision Details Date Name/Position Signature 14-Feb-2012 For Information Marc Blackmore \\AUCBR1FP001\Projects\60092506 - GDE Stage 2\8. -

1 Governance and Accountability

Management Plan Quarterly Review January 2011 to March 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Our Values......................................................................................................................................................................4 Our Management Plan 2010 – 2013 ..............................................................................................................................5 Our Purpose ...................................................................................................................................................................6 Our Charter.....................................................................................................................................................................7 Our Code of Conduct.....................................................................................................................................................8 Our Current Council ......................................................................................................................................................9 Equal Employment Opportunity Management Plan..................................................................................................10 1. Economy...................................................................................................................................................................12 11 Economic Development .......................................................................................................................................................................13 -

Destination NSW Annual Report 2019/2020

INDEX & ACCESS Heading H2 Heading H3 DestinationUnt a cus, optia consequas volupidis voluptas alitasp NSW eribeaquame officab orehentio to magnate nonecabore, odita ilit quias que modita perum alibus. Henitiis dollut aperrovitin rererup tatur, sandit invel magnatus. Ame volorit veniscium voles dolumquodic tem rerum necus ANNUALsant fuga. Name rerum unt, eaqueREPORT re net ullaturenet ipsant ma comnis sit a vendeli genureius ma niendis plignih illabo. Ita ipitati onseque nemquibus aut aute cusdae voluptate nat rat. Cil il is rest platest et rate aliquam dolum faceseque derovit, atissusam quis eum re volorep edipsan daector eprorepelest 2019-2020verum que sintureperor simaximus et andis eat as dusa poriatium ant, qui andi consequam ima volo essit, nus cuptati busdaeria aborectibus, odi conseque esecus dolorem iunt as conseque voluptaturit laccus dolorit ipiet quaepro totatur epernatum enitatust, solorum eveliqu asperum is magnata turiorro quuntiam quostem porepe volum rem videnet ut quibus aut enistrum quaepro rerfera temquam autem etur audam faccusa nullam, undi quatibus eos simus re perroreictem eos sunt, ut volest, to ipsam quas ea conem lacerum exerae. Uptis endias estrum que pe pra DESTINATION NSW // Annual Report 2019-2020 Page 1 Destination NSW ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 The Hon. Stuart Ayres MP Minister for Jobs, Investment, Tourism and Western Sydney 52 Martin Place SYDNEY NSW 2000 30 November 2020 Dear Minister, We are pleased to submit the Annual Report of Destination NSW for the financial year ended 30 June 2020 for presentation to the NSW Parliament. This report has been prepared in accordance with the provisions of the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984, the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Regulation 2015, the Government Sector Employment Act 2013, the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983, and the Public Finance and Audit Regulation 2015. -

Approved Routes for 14.50M Controlled Access

National Class 3 Controlled Access Bus Exemption Notice 2019 Approved Roads Road From To Restrictions / Conditions (if applicable) Adelaide Avenue Cotter Rd Capital Circle Agar Street Ginninderra Dr Masterman St Aikman Drive Ginninderra Dr Emu Bank Ainslie Avenue Cooyong St Gooreen St Ainsworth Street Kitchener St Mawson Dr Akuna Street London Cct Cooyong St Albany Street Collie St Gladstone St Alderson Place Tralee St End Alfred Hill Drive Kingsford Smith Dr Alpen St Alinga Street East Row Marcus Clarke St Allsop Street Childers St Marcus Clarke St Alpen Street Alfred Hill Dr Copland Dr Anketell Street Athllon Dr (north intersection) Athllon Dr (south intersection) Anthony Rolfe Avenue Gundaroo Dr Horse Park Dr Antill Street (1) Northbourne Ave Madigan St Antill Street (2) Knox St Aspinall St Anzac Parade Limestone Ave/Fairbairn Ave Constitution Ave Archdall Street Osburn Dr Ginninderra Dr Arnott Street ACT/NSW Border End Ashkanasy Crescent Copland Dr Clancy St Ashley Drive Sternberg Cres Johnson Dr Aspinall Street Antill St Stirling Ave Athllon Drive Hindmarsh Dr Drakeford Dr (south intersection) Baddeley Crescent Kingsford Smith Dr Alpen St Badham Street Cape St Antill St Page 1 of 19 National Class 3 Controlled Access Bus Exemption Notice 2019 Approved Roads Baillieu Court Lysaght St Lysaght St Baillieu Lane Baillieu Court Heffernan St Balcombe Street Sidney Nolan St Box Hill Avenue Baldwin Drive Ginninderra Dr William Slim Dr Bandjalong Crescent Caswell Drive Bindubi St Bangalay Crescent Streeton Dr Carbeen St Barr Smith Avenue Hurtle Ave Athllon Dr Barraclough Crescent Clive Steele Ave Ashley Dr Barrier Street Ipswich St Newcastle St · No right turn permitted into Ipswich St. -

Classroom-Canberra-2021.Pdf

2021 CLASSROOM CANBERRA THE POWERFUL STORY OF 02 9540 0999 KOKODA VETERAN [email protected] REG CHARD p4 unearth-ed.com.au CANBERRA SYDNEY BATHURST MELBOURNE SNOWFIELDS BLUE MOUNTAINS BALLARAT JAPAN NEW ZEALAND Your venue of choice on the ACT’s doorstep ... Warrambui offers group accommodation facilities in a peaceful bush setting. Enjoy “They showed really the tranquil surroundings while staying with us for your camp, conference or retreat. lovely, friendly attitudes • Accommodation for groups from 20 to 200 people and I appreciated all the • Two styles of accommodation: dorm and ensuite • Full catering with delicious meals to suit all ages flexibility and care for us” • Located near Murrumbateman on the Barton Highway, just north of Canberra • A range of day and night on-site activities • Conference facilities and break-out rooms SL17026-0417 Ph (02) 6220 1000 • [email protected] • www.warrambui.com.au Managing Director’s Letter 2021 contents Your guide to the very best Canberra has to offer! “The Canberra Trip” is a rite of passage that has continued to inspire students for over 80 years! The merits are discussed in detail by industry 03 MANAGING luminaries later in this planner. We all have fond memories of when we DIRECTOR’S went to Canberra, often senior public figures recall it was their school LETTER Canberra trip that inspired them to pursue a career in public office. 04 UNEARTH-ED In our companies 95 years of operation we have never experienced such Digs in for Ugandan charity catastrophic conditions. Unearth Ed arranges travel for around 9,000 05 REG CHARD students from all over Australia each year, who visit Canberra and the The story of War Snow and not one student travelled to Canberra with us in 2020. -

RACE Information and Programme

A.C.T CROSS COuNTRy Club Proudly Presents RACE INFORMATION AND PROgRAMME Canberra Runner No.196 May 2010 Official Newsletter of the ACT Cross Country Club ISSN 1324-7557 | Print Post Approved | Publication No. 299436/0081 AbOuT ThE ACT A MESSAgE from OuR active, and to join with other like-minded individuals, So what better way to celebrate the benefits of running Cross COuNTRy Club Race PATRON, ROb DE CASTEllA young and old, local and visitors, elite and recreational, than with a festival. and to be as one in the enjoyment and celebration The ACT Cross Country Club (the Club) is a not for Welcome to the inaugural Canberra Road Running of running. I was delighted when the idea of the Canberra Road profit, incorporated association managed by runners for Festival. This new event marks a milestone for running Running Festival was first mooted by the ACT Cross the benefit of its members and the wider ACT community. in the Capital, and I’m thrilled to be able to support I look forward to seeing you all at Manuka. Country Club – it provides another reason for runners We are the largest running club in Canberra, serving the ACT Cross Country Club and be part of the it. I of all levels and ages to get together for competition the running community of the ACT and surrounding know that this year has been a bit rough and turbulent Rob de Castella and fun. parts of NSW. The Club has over 1,200 members of in Canberra for those passionate about marathon Event Patron all standards and ages (from elite runners to walkers running, but like many difficult times, what finally Under the direction of Race Patron Rob De Castella, and from school age eventuates is often better and more exciting then what the Canberra Road Running Festival made a clear to veterans). -

Explore- Your Free Guide to Canberra's Urban Parks, Nature Reserves

ACT P Your free guide to Canberra's urban parks, A E R C I K V S R A E Parks and Conservation Service N S D N nature reserves, national parks and recreational areas. C O O I NSERVAT 1 Welcome to Ngunnawal Country About this guide “As I walk this beautiful Country of mine I stop, look and listen and remember the spirits The ACT is fortunate to have a huge variety of parks and recreational from my ancestors surrounding me. That makes me stand tall and proud of who I am – areas right on its doorstep, ranging from district parks with barbeques a Ngunnawal warrior of today.” and playgrounds within urban areas through to the rugged and Carl Brown, Ngunnawal Elder, Wollabalooa Murringe majestic landscape of Namadgi National Park. The natural areas protect our precious native plants, animals and their habitats and also keep our water supply pure. The parks and open spaces are also places where residents and visitors can enjoy a range of recreational activities in natural, healthy outdoor environments. This guide lists all the parks within easy reach of your back door and over 30 wonderful destinations beyond the urban fringe. Please enjoy these special places but remember to stay safe and follow the Minimal Impact Code of Conduct (refer to page 6 for further information). Above: "Can you see it?"– Bird spotting at Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve. AT Refer to page 50 for further information. Left: Spectacular granite formations atop Gibraltar Peak – a sacred place for Ngunnawal People. Publisher ACT Government 12 Wattle Street Lyneham ACT 2602 Enquiries Canberra Connect Phone: 13 22 81 Website www.tams.act.gov.au English as a second language Canberra Connect Phone: 13 22 81 ISBN 978-0-646-58360-0 © ACT Government 2013 Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to ensure that information in this guide is accurate at the time of printing. -

DRAFT CANBERRA URBAN LAKES and PONDS Land Management Plan

DRAFT CANBERRA URBAN LAKES AND PONDS LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN Draft Canberra Urban Lakes and Ponds Land Management Plan a © Australian Capital Territory, Canberra 2019 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from: Director-General, Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate, ACT Government, GPO Box 158, Canberra ACT 2601. Telephone: 02 6207 1923 Website: www.environment.act.gov.au Email [email protected] Privacy Before making a submission to this management plan, please review the Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate’s privacy policy and annex at www.environment.act.gov.au/about/privacy. Any personal information received in the course of your submission will be used only for the purposes of this community engagement process. All or part of any submissions may be published on the www.environment.act.gov.au website or in any subsequent consultation report. However, while names of organisations may be included, all individuals will be de- identified unless prior approval is gained. Accessibility The ACT Government is committed to making its information, services, events and venues as accessible as possible. If you have difficulty reading a standard printed document and would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, such as large print, please phone Access Canberra on 13 22 81 or email the Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate at [email protected] If English is not your first language and you require a translating and interpreting service, please phone 13 14 50.